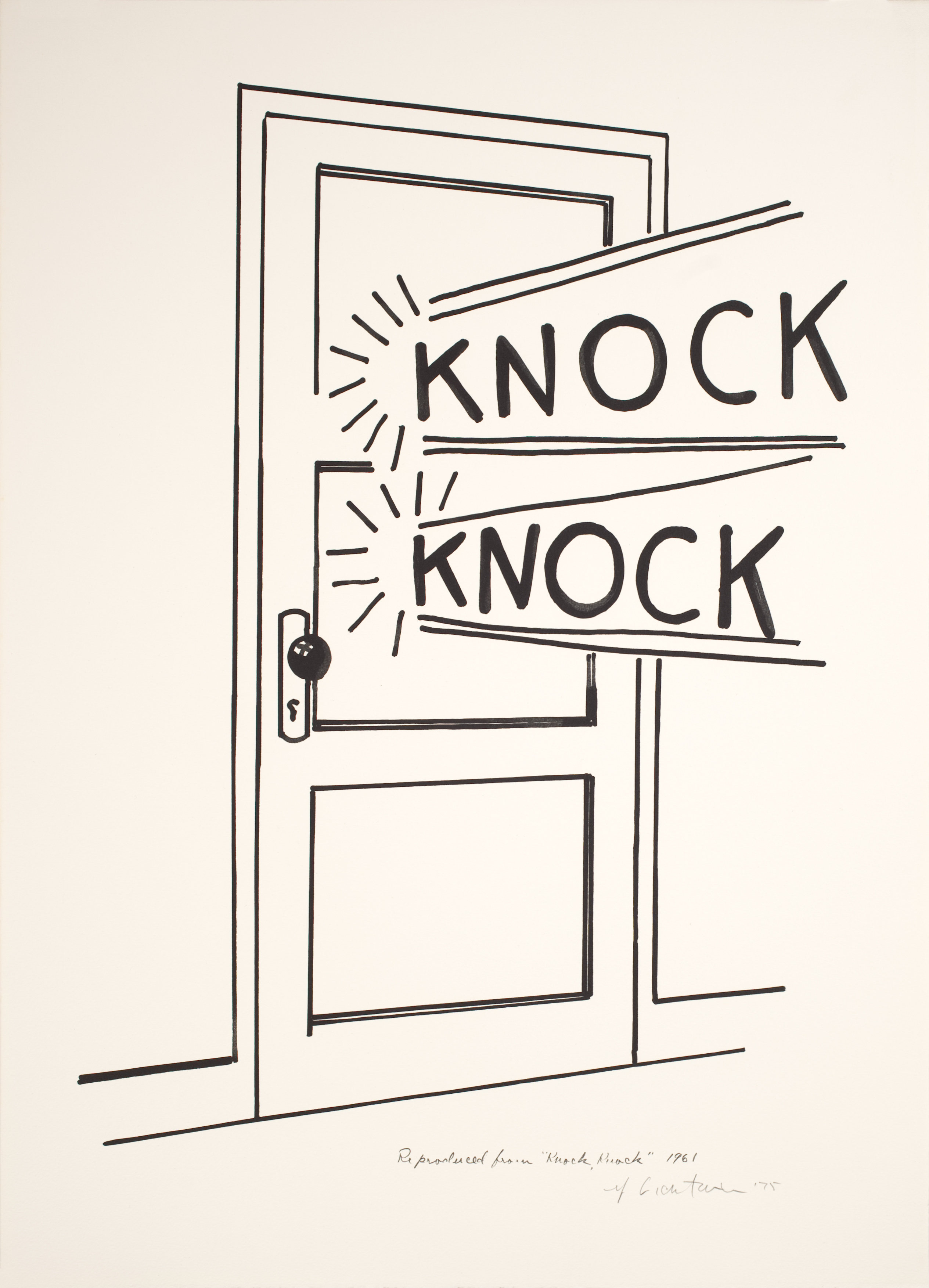

The new annex of the South London Gallery

opened this week, introducing the new (old) digs—a nineteenth-century fire station converted by gallery hotshots 6a Architects—alongside its inaugural exhibition Knock Knock, a survey of more than thirty artists exploring humour in their work (a topic Elephant covered last year in issue 33—read all about it here!). As the media equivalent to explaining your own joke, you can understand my suspicion toward the anticipated scenario of a curator and architect parsing exactly why the show is hilarious and the building inspiring. But SLG’s director Margot Heller and 6a co-founder Stephanie Macdonald had an amusing story to tell: the serendipitous gift and miraculous fifteen-month conversion of a crumbling, water-sodden fire station into a spotless white cube space with echoes of its many eccentric past lives, including the HQ of Kennedy’s Sausage Factory.

- Peckham Road Fire Station, 1905. London Metropolitan Archives, City of London/Collage: The London Picture Archive

- South London Gallery Fire Station, Exterior View, 2018. Photo: Johan Dehlin, Courtesy 6a architects

The building has been through a hell of a lot in its 150-year history. While Knock Knock has rounded up bigshots like Maurizio Cattelan alongside emerging names like Bedwyr Williams and Pilvi Takala to solicit laughs, the most genuine and rewarding jokes come in the historical conundrums and speculative future of the fire station’s elegant resurrection. The architecture itself is riddled with surreal stories that tickle the imagination, both hidden in the old masonry and created fresh through the juxtaposition of the station’s ultra-functional, oft-chaotic past and the zen airy art-world architecture.

Immediately upon entering the building, a faint glitter trail of If There Were Anywhere but Desert, Friday—

one of Ugo Rondinone’s sad sleeping clowns slumbering in the adjacent ground floor gallery—is sprinkled across the original hoof-proof brickwork floor like fairy dust. Meanwhile, two floors up, a designer kitchen lovingly crafted by 6a eagerly awaits its first use—with instruction manuals for the oven still tucked inside the appliance. The anticipation of these polished, silent surfaces has all the tenderness, uncertainty and performativity of an open house day; while glittering golden light fixtures and elegant curved basins could easily be an installation piece criticizing the housing crisis, or perhaps the dark side of the sharing economy, with designer homes tailor-made to a particular aesthetic of luxury travel are largely sitting empty.

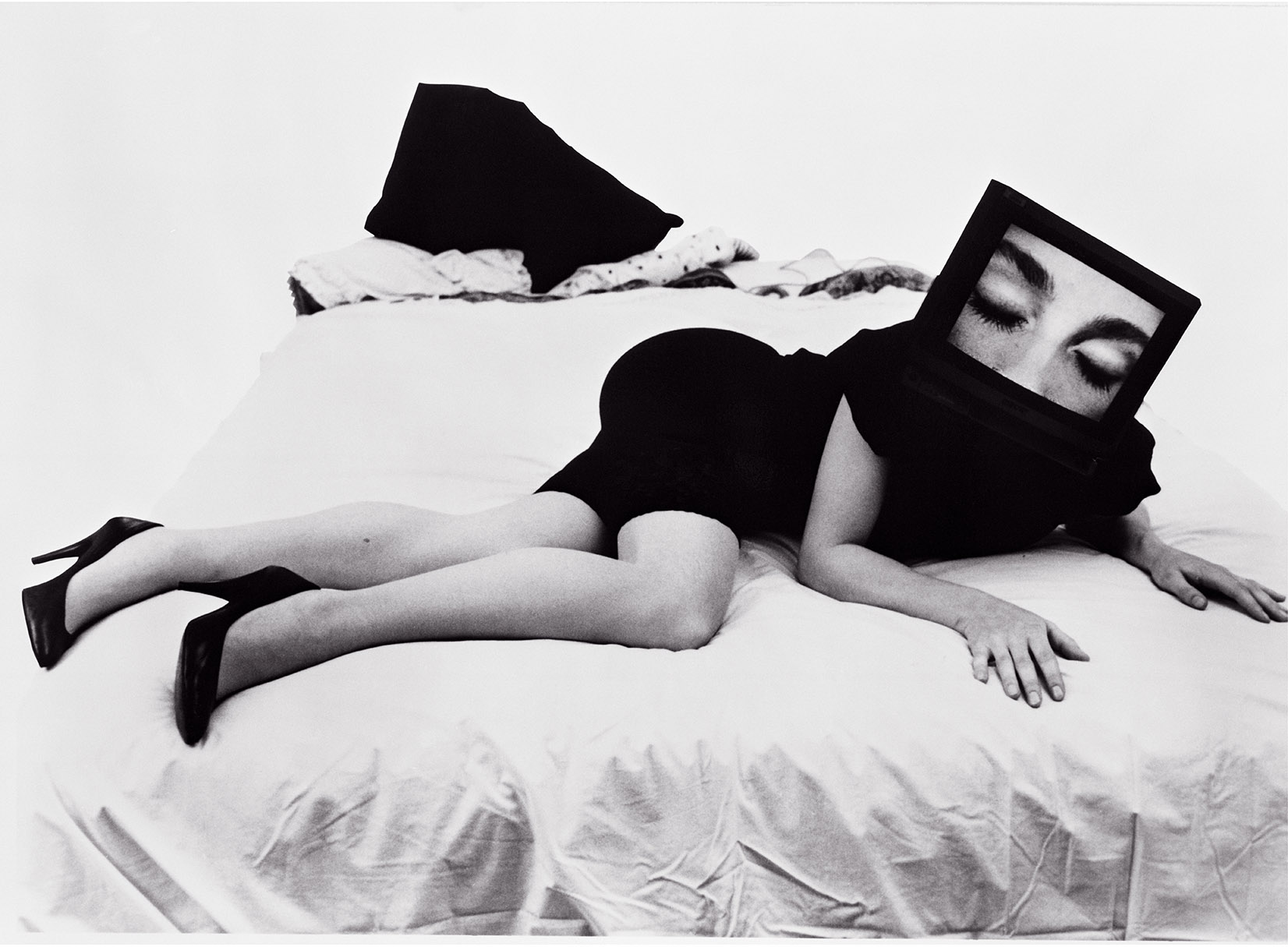

The mental image of a performance or installation where drone propellers become cake batter mixers or Roombas play host to migrating dishes of a five-course meal—the resulting havoc awaiting such an immaculate showroom—makes me crack a smile. As do the architecture writers opening every cabinet, testing the faucets and gaging the materiality of the fixtures. The scene unfolding in the actual gallery next door isn’t much different—what looks like a herd of critics dressed in all black are crowding around a clunky TV screen showing The Horse Impressionists by Lucy Gunning. The artist makes bizarrely funny, grotesque noises—caught between neighing and a guttural shriek, I hesitate to call them human. The whole set-up screams nineties, and everyone’s attention is clearly elsewhere: nostalgically drinking in the endearing obsolescence of this black box, its wiry aux cords and a pair of fat speakers that cartoonishly just out from either side of the screen like animal ears. The archaic fixation is amusing indeed.

Hustling through the old building, I almost collide with a furry bicycle cloaked in the spectacular curling horns and bleached skull of a Welsh Mountain Ram. Whether genuinely funny, startling or merely filled with delirious relief from not KO-ing the sculpture (Fucking Inbred Welsh Sheepshagger by Bedwyr Williams) and causing a multi-thousand pound art disaster, I find myself laughing once again.

“Telling the same joke over and over gets boring, especially if it’s a one-liner built on a recurring hype”

In the main gallery, I find the heavy-handed humour of Martin Creed’s signal-bar of cacti and Ceal Foyer’s handsaw jutting out through the gallery floor (wherein a thin line of black masking tape is supposed to be a convincing substitute for an actual incision)—even Maurizio Cattelan’s signature taxidermy and Rondinone’s sad clowns leave me wanting more. Telling the same joke over and over gets boring, especially if it’s a one-liner built on a recurring hype. It’s the less kosher, unphotogenic moments—like the shared joy of noticing stray glitter on an old floor well-trodden by horses, now elevated to the status of a charming and considered interior detailing of a brilliant new art space—where delight flowers serendipitously, both weightlessly and infectiously, just as real laughter does.

But that’s how humour works. It riffs off everything else, whether that’s literally recycling content in the post-copyright internet age, or through establishing new kinds of jokes with their own codified language, like memes, or happy accidents in institutional spaces that reveal a sense of chance and humility in an otherwise obsessively controlled context. While laughter is a universal experience that has a profound capacity to bridge cultural divides and foster a sense of communality, what makes you laugh ends up revealing a lot about you.

Paying attention to which pieces in Knock Knock tickle my laughstrings (and those of others) ends up being an extended silent banter of its own accord. That laughter—sometimes tacit, sometimes audible—ripples through both the knowing smirks of the people who get the old references, and the eyerolls of a younger generation growing bored with the reigning kings of comedy, like conceptual and postmodern artists Cattelan and Creed. While laughter exists in and enhances the present—whether as a form of collective celebration, or as a brief respite from the overwhelming darkness of politics today—comical art has a magical capacity to reflect the evolution of the art world, and who’s about to get the vaudeville hook.