When Anna Lukashevsky arrived in Haifa, Israel, in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was obvious who she needed to paint: a generation of older women immigrants belonging to the Russian diaspora in Haifa. A mass wave of post-Soviet immigration to Israel followed Mikhail Gorbachev’s lift on restrictions on leaving the USSR. Lukashevsky fled her native Lithuania with her sister. “We can’t even answer the question of why we came, we just ran, like rats from a ship,” she remembers, when I meet her at her studio in Haifa. “We didn’t know anything about life here, we just went where you could go. It was very brutal. We had no money, we lost everything. But I hated it there—I hated the Soviet Union, where everything is grey and average. We were very poor, my Father was a drunk, and then the Nationalist regime came in, and that was no better.”

When Anna Lukashevsky arrived in Haifa, Israel, in the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was obvious who she needed to paint: a generation of older women immigrants belonging to the Russian diaspora in Haifa. A mass wave of post-Soviet immigration to Israel followed Mikhail Gorbachev’s lift on restrictions on leaving the USSR. Lukashevsky fled her native Lithuania with her sister. “We can’t even answer the question of why we came, we just ran, like rats from a ship,” she remembers, when I meet her at her studio in Haifa. “We didn’t know anything about life here, we just went where you could go. It was very brutal. We had no money, we lost everything. But I hated it there—I hated the Soviet Union, where everything is grey and average. We were very poor, my Father was a drunk, and then the Nationalist regime came in, and that was no better.”

Coming out from behind the Iron Curtain, Lukashevsky explains that her art education was cut off at Egon Schiele. “I knew nothing about contemporary art.” She explains that “like all Jewish children”, she had painted and studied art history, particularly Russian Impressionism, but she initially trained as a graphic designer. Seven years ago, “tired of serving Satan”, she quit and returned to painting, and to the Russian women of Haifa who she had first noticed when she arrived in her adopted home. Locally in Haifa, the Russian population are known for their particular style and attitude—maintaining many Russian traditions but fused with their Middle-Eastern surroundings. Lukashevsky’s portraits catch them in their most natural moments. (“When you paint from observation, all the answers are there.”)

“I hated it there—I hated the Soviet Union, where everything is grey and average”

It was at this time that Lukashevsky formed a group with four other post-Soviet feminist painters in Haifa, known as the New Barbizon group. Although they each maintain their individual practices, they share common interests in social realism and portraiture, analysing the position of Russian immigrants in Israel, many of whom have remained closed in their own culture and customs in Israel. Yet the women also speak subtly about the wider conflict between East and West, religion and secularity, women’s beauty and freedom. “We understood that our process is the concept—besides the fact we are five politically-engaged feminist women—the medium is the message. We believed the artist has to come out of the studio, and into the streets, to paint real life.” Painting outside means their work is engaged very directly with their public. “People never see artists on the street, so they don’t understand what you’re doing. They ask, why are you painting here, why this? Are you from the government?!”

“We are five politically-engaged feminist women—the medium is the message”

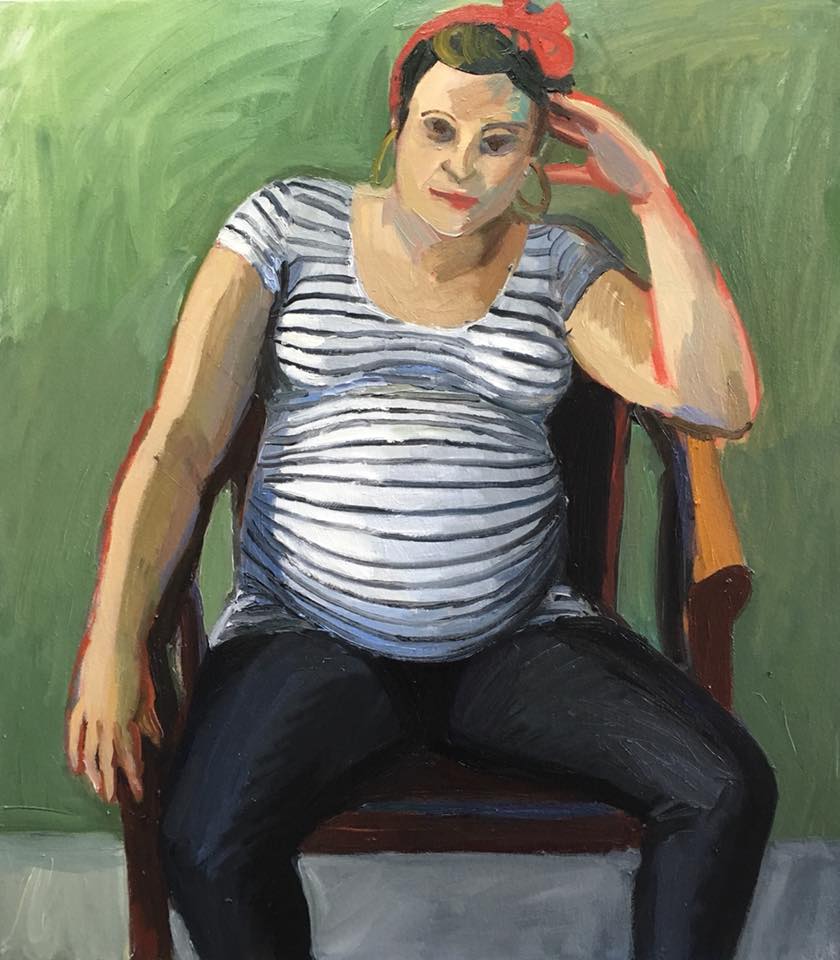

Since the 2015 series of portraits of post-Soviet women, Lukashevksy has touched on many social themes in her portraits, painting mostly lower working class subjects, in Israel and abroad, and moving between formalism and realism; she is often tormented by this and the complexity of painting other people—much like Alice Neel once was. “After two hours with my subject, I have to go to sleep. You have to have some kind of interaction, but it becomes a psychology session, people cry, and I have to work, I am automated.” Recently, she has completed a painting of her hairdresser, who she has known for years. In a role reversal, while sitting at Lukashevsky’s studio, her hairdresser suddenly opened up, and confessed she had spent two years as a patient on a psychiatric ward. Lukashevsky consistently hints at the darker moments of a woman’s life, her isolation, loneliness and suppressed sexuality lingering not far below the surface.

Since the 2015 series of portraits of post-Soviet women, Lukashevksy has touched on many social themes in her portraits, painting mostly lower working class subjects, in Israel and abroad, and moving between formalism and realism; she is often tormented by this and the complexity of painting other people—much like Alice Neel once was. “After two hours with my subject, I have to go to sleep. You have to have some kind of interaction, but it becomes a psychology session, people cry, and I have to work, I am automated.” Recently, she has completed a painting of her hairdresser, who she has known for years. In a role reversal, while sitting at Lukashevsky’s studio, her hairdresser suddenly opened up, and confessed she had spent two years as a patient on a psychiatric ward. Lukashevsky consistently hints at the darker moments of a woman’s life, her isolation, loneliness and suppressed sexuality lingering not far below the surface.

“It becomes a psychology session, people cry, and I have to work, I am automated”

The arresting portrait—a woman with elegant, classical features and coiffed hair contrasting with the wistful gaze on a blue background—is part of a new series Lukashevsky is currently focused on. Her subjects are all, “lonely women aged fifty” from different social classes. One of her subjects is a former model. Her body dominates the painting, poised, sexual and provocative. “I was living in her flat in Tel Aviv while we did the painting, and she totally commanded me during that time—she was manipulating me!” Lukashevsky recalls. “Every night she was drunk and stoned, of course, and so was I… She knows herself very well, she’s self-conscious, but she’s deluded.” Next to this painting is another woman in her fifties—the complete opposite—a woman who works as a translator, an academic from Lukashevsky’s circle. Her look by comparison is cast down; unconfident and shy. The atmosphere is mirrored in a palette of sombre hues; her dress, gaze, and pose all reflect the relationship between class, womanhood and how we see ourselves.

Rather than project a set of idealized ideas about being fifty, Lukashevsky—who is still in her forties—simply observes the women she is drawn to very closely, and captures what she sees. Fifty is a notoriously difficult time for women, as many hit the menopause. In representing these women as complex individuals Lukashevsky avoids steretoyping, but she represents an invisible community of women who need to be seen. Just last month, the fifty-year-old French novelist Yann Moix publicly commented in an interview with a glossy magazine that women over fifty are “too old to love”. Their bodies, he claimed, are “not extraordinary at all”. Surely this is ample proof of why more complex and humane explorations of women at this age are needed, in a world that favours the super young.