After graduating with a masters from the Royal College of Art, Olivia Twist has adorned many different surfaces with her illustrations. She explores, upholds and validates the mundane; thick lines and loud colours shape scenes from the chicken shop run, Ridley Road Market, and the sanctity of the barbershop experience. Human-centred interactions are at the heart of Twist’s practice, fuelled by her work as a lecturer at Camberwell College of Arts. Breaking down the traditional structures of academia that other particular students is key to Twist’s educational ethos, and she has a determination to increase access to arts institutions.

Twist grapples with threads of place, intimacy and preservation within her practice. This rings particularly true in a project named For Us, in which she acts as the family archivist. In these works, dark lines are gouged into the page, revealing textured figures, and her close eye for detail ensures that no clothing crease or wistful expression is rendered any less carefully. With this quiet, meticulous attitude, Twist turns the audience into a fly on the wall, privy to moments of intimacy that she shares with her subjects.

“Human-centred interactions are at the heart of Twist’s practice, fuelled by her work as a lecturer at Camberwell College of Arts”

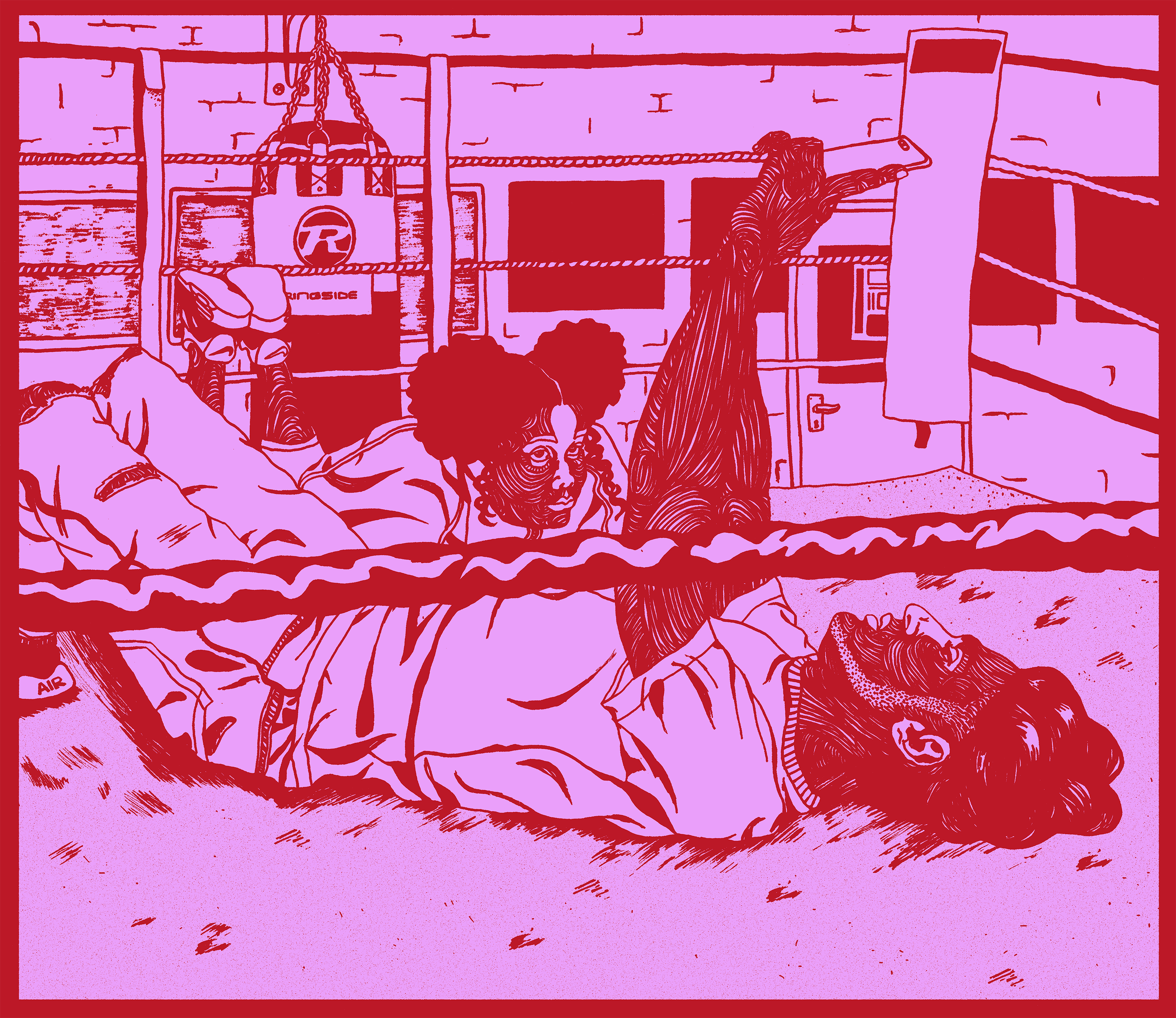

Her ability to capture an atmosphere is heightened in a collaboration with poet Caleb Femi, entitled Goldfish Bowl. Based on Femi’s work, the project interrogates “the small, but defining moments that make up a life”. Co-commissioned by The Albany, Roundhouse and Battersea Arts Centre, Twist’s larger than life illustrations visually magnify the poet’s words, immersing the viewer in her take on his world. Whilst she’s racked up commercial work for WePresent and the Wellcome Collection, it’s these more personal projects in which Twist acts as a visual journalist that showcase the true breadth of her skills.

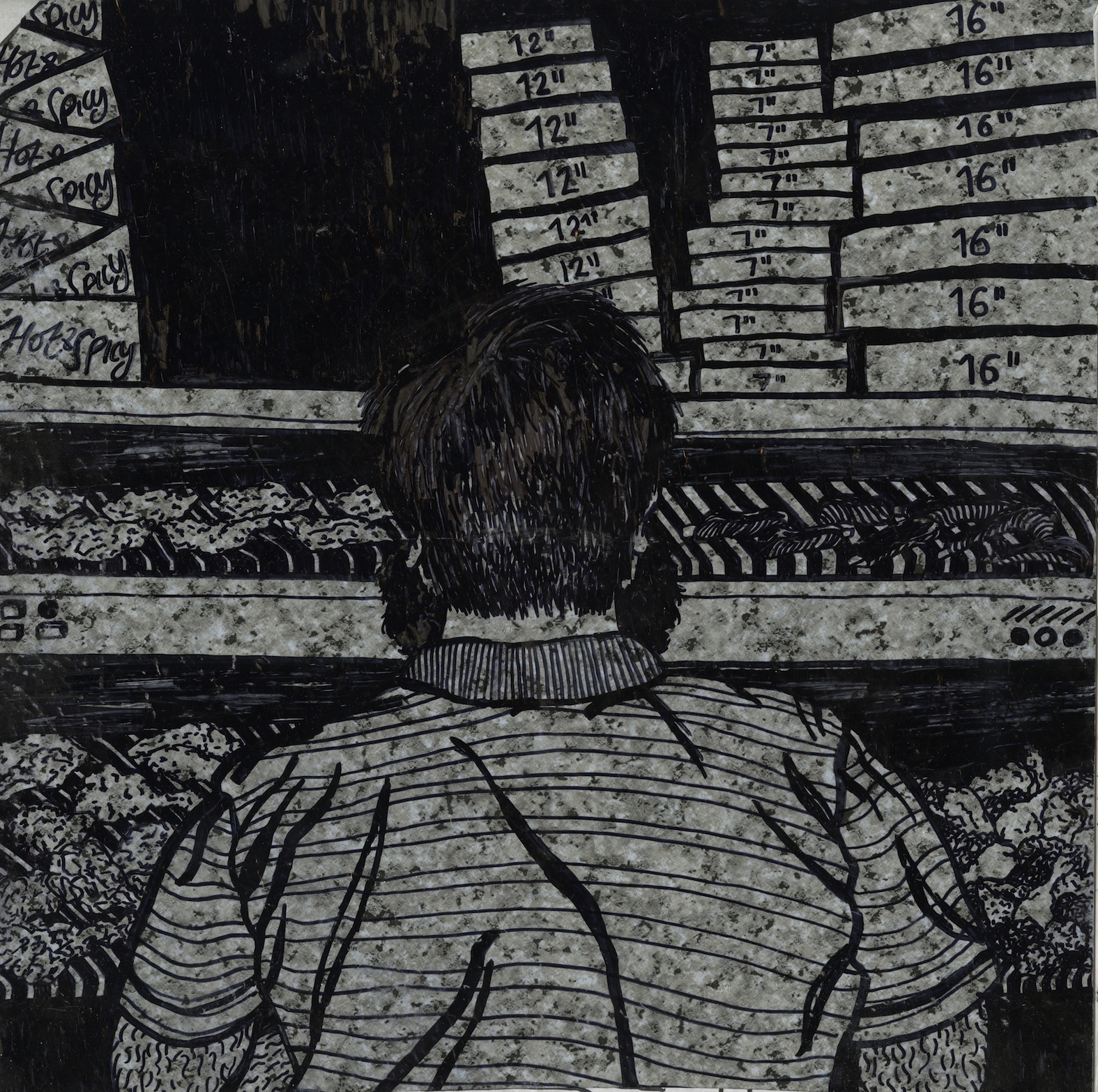

You’re skilled at translating very particular experiences into immersive visual narratives. What is it about these specific moments—such as the teenage pilgrimage to the chicken shop—that you want to preserve?

For me, it’s got to be the joy. The way we laughed a bit too loud, too often. When it was happening, I didn’t realise what a transformative time it was in my life. Moments like that teach you how to banter, they also help you form your circle and help you to begin to understand the fullness of friendship.

I want to preserve everything that comes with those experiences, like the fashion and styles we were doing at the time; it’s good to be able to laugh at yourself. Some of the drawings make me think back to the music charts then, and also parallels what young people are enjoying at the moment. Even thinking about how you put sauce over your food, and how even once you have started working and gone to a few nice restaurants, there is still something about good chicken, chips and ketchup that can just hit the spot. I wanna toast to that through my work. This project particularly has been a talking point between me and my younger brothers, who are currently doing the chicken shop pilgrimage after college with their mates.

Your residency with Carney’s Community explored ‘chosen family and self-expression’. Why did you choose to examine these concepts in particular?

I am really into platonic intimacy and I really value family. I was an only child for 12 years, and I really used to see sisterhood on TV and crave it; I guess because of that, I really value friendship. But then you start to realise that saying ‘blood is thicker than water’ doesn’t always ring true. Culturally, I’ve grown up calling women of no relation to me Aunty, to show respect and reverence. People greet friends of friends and call them Bro. Unity is big around me. And in Carneys, kids who weren’t related by blood were telling me that they’re cousins, because they have pretty much grown up together and have a number of shared experiences. Kinship is real in the youth club and I really admired it and wanted to celebrate it, so I created a mural that had a family photo album vibe, because that’s what the young people told me they wanted.

“Kinship is real in the youth club and I really admired it and wanted to celebrate it”

Social interaction plays a central role within your practice. Does your work as a lecturer and arts facilitator enable this, and how does this relate to your desire for greater access to the arts?

I think my roles as a lecturer and facilitator really help each other. I guess from working with different community groups (ranging from women in prison, to older adults who are part of the Windrush generation, to looked-after young people), I have built up confidence interacting with people. I am actually quite shy. Workshops came before the lecturing and I just wanted to participate in knowledge exchange and encourage people to make and help build their confidence in doing so. Art is for everyone, and everyone is creative. I guess my formal training for my PGCert taught me about learning styles and how to switch things up to ensure everyone feels empowered to participate.

I started lecturing quite soon after graduating, so initially I was very close in age to some of my students. That worked well, as I am approachable and pretty chill. I just want everyone to do well. I want all students to feel like they can really make a career out of this. I bring in visiting staff that reflect the diversity of the cohort. I know academia can feel uncomfortable for some and I want to do what I can to ease that or trample on things that make people feel othered. I encourage my students to see beyond the gallery or design blog, and think about placing their work where the people who inspired it frequent.

The poetic pairing of words with illustrations on your website really sets the scene for the story you’re telling with each project. How does this relationship with words tie into your collaboration with poet Caleb Femi?

Back in the day, maybe like 2014, we formed a creative collective called SXWKS with a few friends. Before that I didn’t have much of a relationship with poetry at all. But spending time with poets, photographers, djs, rappers and all of that, things start to rub off on you. We all encouraged each other to push our practices. I’m not too much of a talker, which is why I draw, but there are just some words and phrases that marry well besides the drawings. So from that collective, I got to work with Caleb a few times, and the most iterative of those times was for his theatre show called Goldfish Bowl, which was also done with the Rapper Lex Amor; it was an exciting process. I did some illustrations and animations for the set design.

- Olivia Twist, For Us/I Am The Family Archivist

I love the project For Us/I Am The Family Archivist, which explores illustration as a tool for demonstrating worth. How do you think illustration has the power to validate?

Illustration is something I believe is incredibly intimate and intentional. You can sit there for seven hours drawing a portrait of someone. It’s a real labour of love and a solid commitment. And when you present the image to someone, it’s a mixture of them and how you see them. Being drawn means you are important. Overlooked communities deserve to have the opportunities to document their stories, and illustration is an accessible way to do so through pairing it with oral history.