Democracy and art have an uneasy yet insistent bond. Democracy is surely vital for free creative expression; yet it has simultaneously been the reason to destroy regions and “liberate” their ruins. Historically, global artworks have portrayed countless struggles for social equality, whether it’s the Spanish Civil War

or anti-apartheid activism. When South Africa’s apartheid regime finally fell in 1994, the Johannesburg-based Constitutional Court also began to host a significant artwork collection symbolizing the country’s new Bill of Rights and future, including Joseph Ndlovu’s expressive tapestry, Humanity.

“Democracy is surely vital for free creative expression; yet it has simultaneously been the reason to destroy regions and ‘liberate’ their ruins”

For generations, art has also grappled with the ideals and illusions of democracy. There’s still definitely a resonant sting to the satire and grotesque detail of William Hogarth’s 1755 series The Humours of an Election, which depicts rival party canvassing, polling and ceremonials in eighteenth-century England. Meanwhile, democracy brings twenty-first-century Britain together and tears it apart, in the wake of 2016’s EU referendum. Early this year, Swedish conceptual artist Jonas Lund provoked the ire of Leave pressure groups with his pro-EU “influencing agency” installation Operation Earnest Voice at The Photographers’ Gallery in London.

- Ewa Axelrad, Fetor, Greetings, 2014

Even the act of voting can feel like a kind of artform; the (possibly toxic) “electoral ink” used to stain voters’ fingers in modern elections from Afghanistan to Turkey carries a heavy symbolism. Around the world, art might be exploited as propaganda by oppressive states, but it also represents the potential for liberty—it sharply captures the shock to our system, when “democracy” does not deliver the results we expect.

Headlines and Hot Takes

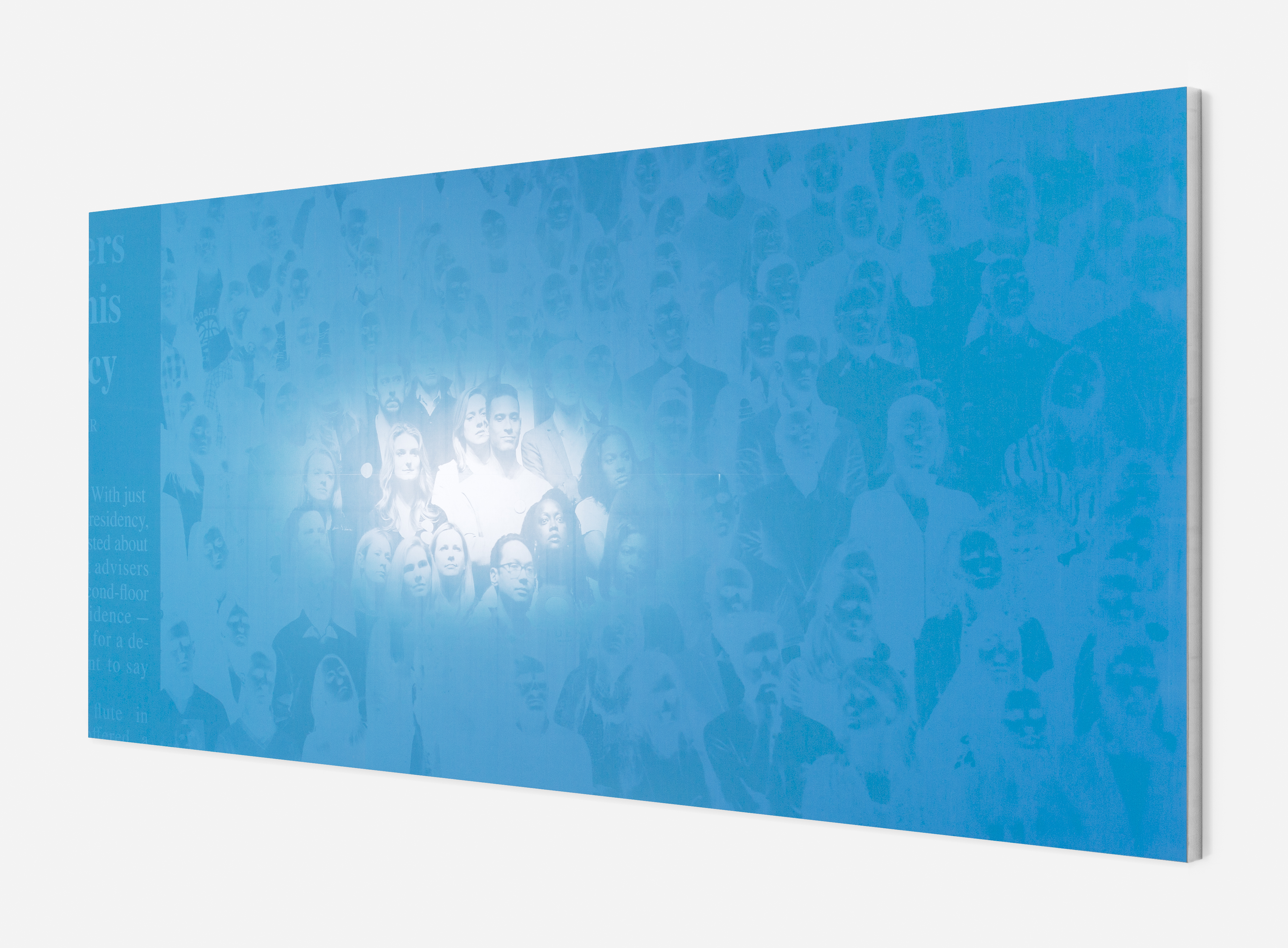

“Democracy is an idea. It is also an ideal. Still somehow we erected it as a myth and detached it both from history and contemporary culpability.” Belgian artist Emmanuel Van der Auwera’s multimedia creations pay testimony to the human

condition, and the way we react to the world around us. When we speak, he’s about to open his first US solo show at Harlan Levey Projects in Dallas, including his Memento series of large-scale news reportage and responses. I was also transfixed by his artworks in the recent group show We Are the People. Who Are You? at London’s Edel Assanti gallery. In Red IV (2018, from Memento), an offset panel from a newspaper printing press details an intense close-up crowd shot of Hillary Clinton’s supporters in the moment that Donald Trump’s US Presidential victory has been confirmed. The monochrome image magnifies the emotional charge; the faces display disbelief, distraction, horror, maybe hilarity. Van der Auwera also subverts a medium of “traditional” news-making in White Noise (2018), where a polarizing filter lens picks out images from a seemingly static white screen; these turn out to be taken from the footage of US strikes in civilian Baghdad, leaked by military whistleblower/heroine/activist Chelsea Manning.

“It was an image we were never supposed to see: a densely populated city gunned down like it were a videogame, the mechanical routine of distanced murder that was outside the language of images projected by mass media,” Van de Auwera says. “It seemed like a turning point, but eventually seemed to have no real legacy or impact. Leaking the video was the ‘right’ thing to do, but in the eye of the audience it wasn’t much different than any serial show or soap opera.”

He suggests that the dislocated myth of “democracy” has lingered over decades, and it’s also at large in his Memento series: “This is what we see in the work where Clinton’s supporters gasp and moan,” he explains. “For half of the country, this is a reaction to horror. For the other half, it’s short-sighted hysteria. Post-modernism allowed for post-everything. Truth included.”

As a European child of the eighties, Van der Auwera’s own first impression of “democracy” came through the 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall (“I was too young to grasp what it really meant, but it felt like light had defeated darkness, or something like that”). The ideal of democracy as a clear-cut force for good is persuasively deep-rooted, yet we now also exist in an era where public opinion is somehow amplified, polarized and shrilly distorted.

“The ideal of democracy as a clear-cut force for good is persuasively deep-rooted, yet we now also exist in an era where public opinion is somehow amplified, polarized and shrilly distorted”

“So-called social media generates a legion of influencers, anonymous popstars and myopic visionaries,” Van der Auwera says. “It’s marketed as utopian: an ultimate expression of direct democracy with a power unmatched in human history. How horrifying. Just imagine the two billion Facebook users, the databases behind it and deep learning technologies that suppress (and soon surpass?) best practices and knowledge pinnacles in our system. I’m in awe when I think about the infinite emojis, trash humour, sex pix, political comments and intimate information gifts channelled into a deep learning machine employed to create fake identities and feed them back to the same stream. This vision of flux, pump, valve—an endless flood of opinions with expressions of fear, anger, cruelty and ignorance—make what is promoted as hopeful feel like a tool of alienation instead of liberation.”

Film As Empowerment

“People sit in their living rooms and watch war footage, but how can they know what everyday life is like there; how people find resilience and resistance, not just to survive, but to live?” said London-based Iraqi filmmaker Maysoon Pachachi to Middle East Institute. Modern media lends the illusion that we are watching democracy unfold in faraway lands, with Western powers as the gatekeepers of this liberation. It is a surreal, disorientating spectacle—as French sociologist/commentator Jean Baudrillard noted in his 1991 essays about propaganda and atrocity, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place. It is also hollow beneath the bombast; decades after the first Gulf War, and its 2003 blockbuster sequel (dubbed “Operation Iraqi Freedom” by the invading coalition), the “liberated” Iraqi voice, and the region’s rich heritage of arts and culture, is scarcely represented in the mainstream.

“Film can be part of the healing process. And for the people making it, an act of resistance and repair”

There are crucial counterpoints to this, such as the work of Pachachi, whose projects have presented an inspiring (and often heart-wrenching) range of expressions, with film and art as an act of human empowerment. Return to the Land of Wonders (2004) depicts post-invasion Iraq with a rare depth and range. It features her father Adnan Pachachi (formerly pre-Saddam Foreign Minister) and Iraq’s interim constitution attempting to create an independent democracy, as well as documenting the hopes, humour and dignity of ordinary Iraqis. In Our Feelings Took the Pictures: Open Shutters Iraq (2005), we engage with a group of Iraqi women creating a photography project in Syria (which was deemed to be safer at the time); its verbal and visual imagery is relatable and resonant, often devastatingly so. Pachachi and fellow Iraqi filmmaker Kasim Abid also co-founded Baghdad’s free, non-governmental Independent Film & Television School. Under previous Western sanctions, many Iraqi film students hadn’t been able to access working camera equipment.

Pachachi is currently filming her first feature movie, Another Day in Baghdad, created with writer and feminist activist Irada Al-Jabbour. Its story portrays intertwined lives in a Baghdad neighbourhood in 2006, at the height of the country’s sectarian violence (its Arabic title Shaku Maku, meaning “nothing doing”, has a particularly Iraqi drollness to it). The project is crowd-funded, and its cast showcases a multi-generational range of acting talent. “Film can be part of the healing process,” says Pachachi. “And for the people making it, an act of resistance and repair.”

Rap For Democracy

In January 2019, ultra-conservative politician Jair Bolsonaro was elected President of Brazil. The country’s “New Republic” democracy was established in 1985, after twenty-one years of oppressive military regime rule; Bolsonaro’s victory represents a throwback to “order” for his supporters, and serious repression for the nation’s social activists and artists. Of course, Brazil also has a rich tradition of creative resistance, and its modern champions include Sao Paulo-born music artist Criolo, whose celebrated material (from 2006 debut album Ainda Ha Tempo) has melded rap/soul/roots/electronic genres and eloquent social critiques.

“Art has this brutal force of communication… I grew up in environments that made me question the world,” says Criolo, who began writing and performing hip hop aged eleven, inspired by the social activism and teaching work of his mother, and the poverty and inequality that surrounded his family home in a Sao Paulo favela. As an emerging artist, Criolo founded the democratically-spirited creative forum, Rinha dos MCs, where local youth could get involved in and showcase their own music and visual art forms, from sculpture and photography to graffiti. In the build-up to Brazil’s latest general elections, Criolo became involved in the project Rap pela Democracia (Rap for Democracy).

- Criolo, frame from Etérea, directed by Gil Inoue & Gabriel Dietrich with creative direction by Tino Monetti & Pedro Inoue

“Rap pela Democracia is one of many attempts to raise awareness about democracy and remember what is at stake here, to remind everyone about the fragility of it,” he says. “Me and my peers do not believe that we are living in a positive political environment. We believe in different, healthier ideas for the country. We are against arming the population, the pro-gun lobby and also the prejudice; people’s hate has been explicit like never before. Xenophobia, homo/transphobia and racism are stronger than ever in Brazil. Our numbers on violence and death are war-like. Art is an efficient form of telling the rest of the world what’s going on.”

In an era of multimedia overload, music remains an exceptionally powerful tool for social protest. It’s worth noting that within the vibrant reverie of this year’s Rio Carnival parade, winning samba school Estação Primeira de Mangueira (one of the city’s most traditional samba institutions) performed a music anthem commemorating trailblazers including Marielle Franco

: an Afro-Brazilian bisexual female politician and human rights activist, who was murdered in 2018. Meanwhile, Criolo’s latest track “Eterea (Ethereal)” is a brilliantly soulful, spirit-soaring statement of LGBTQ solidarity, with a beautiful accompanying video.

“Modern media lends the illusion that we are watching democracy unfold in faraway lands, with Western powers as the gatekeepers of this liberation”

Criolo pays credit to Tino Monetti, the creative director for “Eterea”, and performer D’Avilla, who was responsible for the video’s casting and production. “It’s moving to see people’s reactions, to read the online comments, to hear what people have to say in the streets, on the radio,” he says.

“Brazil is the country that most kills LGBTs in the world. The numbers are alarming, and it’s an urgent social issue. People have to realize that playing with hate kills the ones that are targeted. The performers of ‘Etérea’ fight against prejudice by sharing their kindness, art, intelligence, with others. And they, as well as every LGBTQ collective around the world, have my biggest admiration. Thank you, Ákira Avalanx (House of Avalanx), D’Avilla (Popporn and Festa Dando), Fefa (Animalia), Flip (Amem Collective), Juju ZL and Kiara (Batekoo), Transälien (Marsha Trans and Collectivity Namibia) and Zaila (House of Zion).”

The Desire For Unity

“Every time a conversation about democracy comes up, it ends with the question: was there democracy in the first place?” London-based, Polish-born artist Ewa Axelrad converses with an appealingly warm and wry sense of humour; she also comes across as keenly observant, sensitive to the dynamics around her, and curious about how they’ve been shaped. All of these qualities come into play in Axelrad’s multi-layered sculptures and images, where familiar objects assume strangely mesmerising new forms, and questions arise about belonging and collective identity. Her 2017 body of work Shtamah took its title from a Polish word entailing reciprocal help between allies (with its roots in the German word for “tribe”); its mixed-media works evoked nationalism, military pride and the way that individual identity is subsumed by the collective body.

“Nationalist narratives can be very powerful and destructive,” says Axelrad. “With Shtamah, I was interested in how certain narratives tap into the shared desires of people, and the universal theme of territory.”

“In an era of multimedia overload, music remains an exceptionally powerful tool for social protest”

The themes of her work feel instinctive, drawing from the roots of exclusion, both historically, and on an intensely personal level; her family have been coming to terms with her grandmother’s painful revelation that she was a Holocaust survivor. Her art feels imbued with a deep sensitivity.

Axelrad was just five years old when democracy was introduced to Poland in the late eighties; she recalls the swiftness and celebration of this shock to the system. “Everyone was excited about embracing this change; democracy and capitalism coincided,” she says. “By the time I went to school, there was such an optimism. Everything from the West seemed unbelievably stable, whereas we had been behind.”

Modern political reportage questions the state of Poland’s democracy, with the dominant conservatism/nationalism of the country’s PiS (Law and Justice) party and its clampdowns on the media and judicial system. Axelrad’s work avoids judging society from a distance, though she concedes that: “When you are away from your country, you see certain things more clearly. I was able to see a wider political context.”

Rather than didactic commentary, her art taps into human qualities and desires, occasionally manifested in unusual ways. Her 2014 work Fetor, Greetings retains a strange allure through its subject of “riot tourism”. “It’s people travelling to a place of political unrest to attend a riot, and it’s completely dependent on social media,” she explains. “It’s so telling about how certain societies, usually those who are privileged not to have conflict in their countries; they are intrigued and tempted to participate for the sense of feeling ‘together’. They describe feeling the most intense human experience… Populism grew out of democracy in certain ways; how we inform our choices has changed. What I find most problematic, and fascinating, is how it taps into the emotional aspect: the need for unity.”