Pierre et Gilles

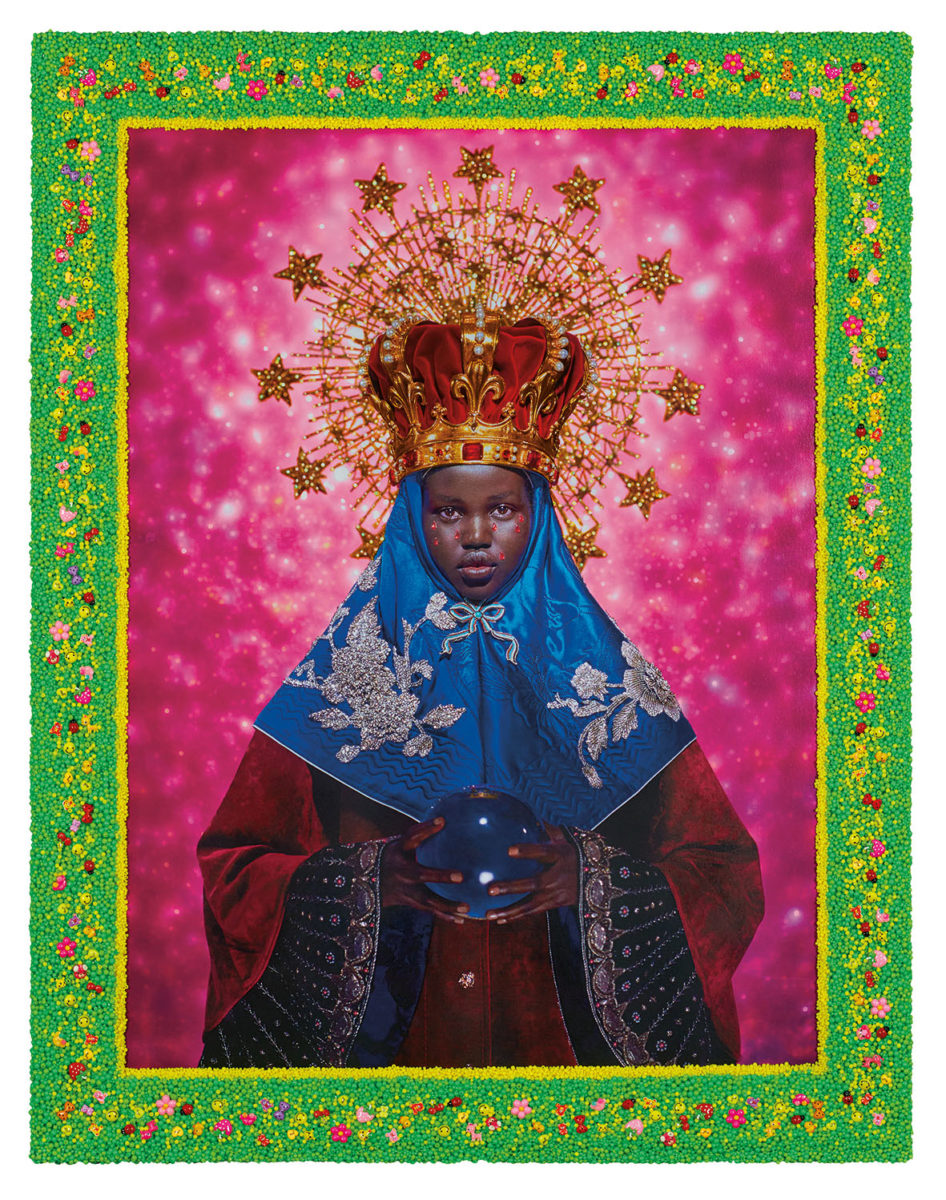

The French artists and romantic partners have collaborated since 1976, melding painting and photography in images infused with pop culture and art history.

Pierre Commoy

Growing up, I was mostly interested in music and the cinema until my parents gave me a little Instamatic camera and I began to take photos. A guy who ran a photography store encouraged me and displayed some of my pictures in his shop window—that gave me a lot of confidence. From then on, my dream was to be become a photographer.

Gilles and I met in a club in Paris. We knew we’d get on well as soon as we were introduced, and after a little time and several drinks, Gilles grabbed me, we went back to mine and… voila! Initially we worked separately—Gilles on his paintings, me on my photography. But then we started to work on a photographic project based on shots from photo booths that I used to collect, mainly images of our friends against brightly coloured backgrounds. I was really disappointed by the ugly colours in the initial prints, but then Gilles had the idea to retouch them, starting with the background colours, then the teeth, then the eyes. I was so happy with the results that we’ve never worked apart since.

“Gilles grabbed me, we went back to mine and… voila!”

Every project we’ve done has been an adventure, which after forty years doing this adds up to a very big adventure indeed. What we’re most proud of is the body of work we’ve built up since the beginning, and whatever we continue to add to it.

Collaboration works for us: you just have to respect one another and give each other certain freedoms. Like all couples, obviously, we have our disagreements—but that’s just normal. We’ve always shared the same interests. We had so much in common from the beginning (from Pop Art to films to weird things we both collect) that when we met we were both a bit blown away to discover we had so many shared tastes!

Our personal and professional lives have been indistinguishable since the beginning, which always seemed completely natural. Even in the recent lockdown, we’re still working: given the circumstances, it seemed like a good moment to make a self-portrait.

Another duo I admire? Starsky and Hutch, the TV cops. They’re a bit like us: one has brown hair, the other’s blonde; one’s an extrovert, the other more guarded. We definitely see ourselves in that—and I’m definitely more of a Starsky.

- Pierre et Gilles, La Vierge Noire, 2018; La Madonne au Coeur Blessée, 2018; La Madonne Voilée, 2018 (left to right). Courtesy the artists and Galerie Templon

Gilles Blanchard

I grew up in a provincial town by the sea, which I liked a lot. But I wasn’t so keen on school: I didn’t work, and my parents despaired about how to educate me. They took me to museums and tried to make me read books, but because I’m dyslexic I never read anything. Eventually, I ended up at art school when I was fifteen. At that age, I had no idea where I was headed, so finding myself at art college changed my life. I loved it and I was a good student—so, you could say I ended up as an artist by default.

My biggest early influence was Pop Art, particularly Richard Hamilton’s collages. I made loads of collages of my own, out of pop images, glitter and joke shop items. This really pissed off some of my teachers, but others loved it—and that’s how I got my degree. I came to Paris at eighteen to attend the École des Beaux-Arts, but I never studied. I was completely lost and basically just hung around in the streets for three years. Then I met Pierre, which determined the course of my life.

We didn’t exhibit much at the beginning. Art at that time was very conceptual—très intellectuelle—and I couldn’t find my place in that context. Then in the late 1970s, the art world began to change; people like Cindy Sherman came on the scene, and we understood that it was our moment.

“We’re quite unalike, me and Pierre, and that’s why the relationship works”

Our professional and personal lives are a happy mix. We’ve always worked at home: we started out in a tiny studio (about 35m2) in the Marais, and then spent eight years in another space in Bastille. Eventually we decided to look for somewhere a bit bigger in the banlieue, and found our current home just outside central Paris. Our work these days involves all sorts, from styling to going out shopping for props. Everything is very artisanal—we make everything ourselves.

We’re quite unalike, me and Pierre, and that’s why the relationship works. We have shared sensibilities, but our approach is very different. We need each other to create. When I was a child, I always needed a best friend—a double, if you will—and I now know I was always looking for one. Good thing I had the strength to find him!

As told to Digby Warde-Aldam

Jane and Louise Wilson

The British identical twins have worked together for over two decades, using film and photography to explore the overlap between art and architecture.

- Jane and Louise Wilson, Casemate SK667, 2006 (left); Untitled #7 'I'd Walk With You But Not With Her', 2018 (right). Courtesy the artists and Gallery 303

Louise Wilson

Growing up, we weren’t working on the same drawing as such, but we were always making drawings in the same space together. We used to spend most weekends with our father’s mum, and she had a house that had pretty much stood still since the 1930s. There was no television, but there was a radio and lots of books. She really encouraged us to paint and draw and make things.

We did an art foundation course together, and Jane decided she wanted to go to Newcastle Polytechnic, and I went to Dundee. We didn’t feel we needed to separate as such, but it opened up another space because we were 300 miles apart. If we’d just been living and working together, it might not have been so interesting.

I don’t think we really separate art and life. For some people it’s important to make that separation, but for us making the work feels part of your life; you’re defined by it so much. Until recently we were living together. Within that there’s always a discursive space, and that’s how we are as a family.

The biggest challenge is trying not to repeat ourselves. Often, because we’ve discussed something, I’ll be talking to someone about it when we’re socialising, and then five minutes later Jane will come up and say the exact same thing. It can weird people out sometimes.

“A good collaborator is someone who is prepared to go along without being able to predict or define what the outcome will be”

But, having said that, it’s intensely rewarding to have such an expansive space together, and it is one that has the potential to extend with other people. We’re working with other artists, curators and writers at the moment. I think it really opens things up, and it can be a really exciting extension of how we work together.

Collaboration is the impulse behind what we do. It’s something that we’re not so self-conscious about; it’s just part of our practice and part of how we work. The Coen Brothers are a great example of a creative duo, and of a family endeavour. As identical twins ourselves, it’s really interesting to see how siblings come together, but also just how relationships work.

A good collaborator is someone who is prepared to go along without discussion, and without being able to predict or define what the outcome will be. It’s because of the collective effort that it becomes what it will be, and that’s where its agency lies.

Jane Wilson

When we were at art college, we were surreptitiously working together to stage photographic setups. While we were at separate colleges, we would always say, “Oh, and this is something I’ve been doing with my sister,” you know, a little bit coy. It became more and more obvious that those were the pieces that were actually very interesting, and that was where our ideas were really gelling—in that dialogue together.

We’ve always been very connected to site and to space. We’re often thinking of this idea of the double-consciousness, identity, and the fluidity of all of these things. With the staging of our identical degree shows, it became absolutely clear that it was the only way we could manifest the work properly.

It grew out of the ideas we were sharing and the exchange we were having. It also became clear that, as a work, it was something that represented both of us. Certainly, with our piece named Garage, which we staged in our parents’ garage, it was very much a shared psychic space that we had inhabited together since childhood.

The art world still cannot let go of the notion of the individual and it has this very mundane approach towards what it values as “the artistic statement”. It can’t see a double. I think we are playing with that and creating something that is a lot more speculative, about why that idea of the individual needs to be so fixed and so enshrined.

“I don’t feel this shared sense of dialogue with anyone in the way I have it with my sister”

Also, we are in a culture now where other identities have been expanded out into trans or other associations of gender. People are constantly playing with their notion of how identity is perceived. But it seems that still, within the art world itself, it’s not an easy thing to accommodate. And I think that with the two-ness of us, it also is difficult, and frankly because we’re two women.

I don’t feel this shared sense of discussion or dialogue with anyone in the way I have it with my sister. I don’t think it’s a closed thing, as some people imagine, it’s just that we have this discussion between us. It has the potential to expand and involve other people, and other partners and other situations. I wouldn’t want to do it without Louise. I think that’s a big point, really. It is a shared life and that is very important to us.

As told to Louise Benson

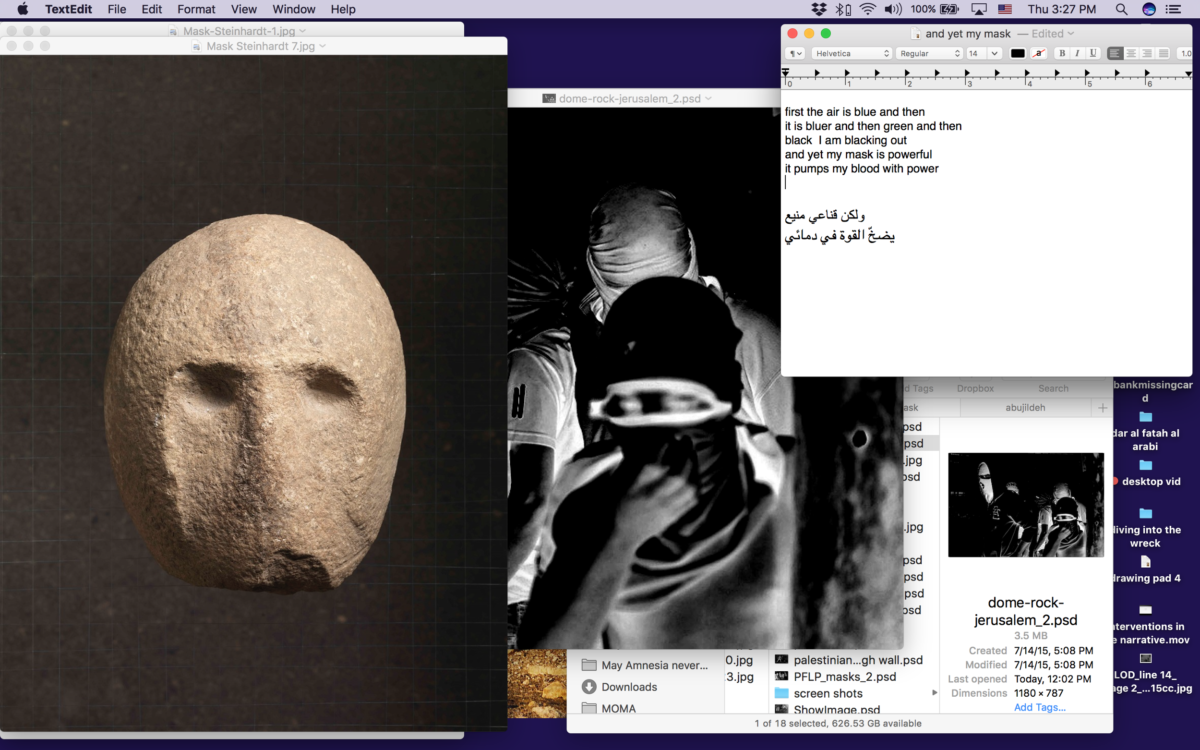

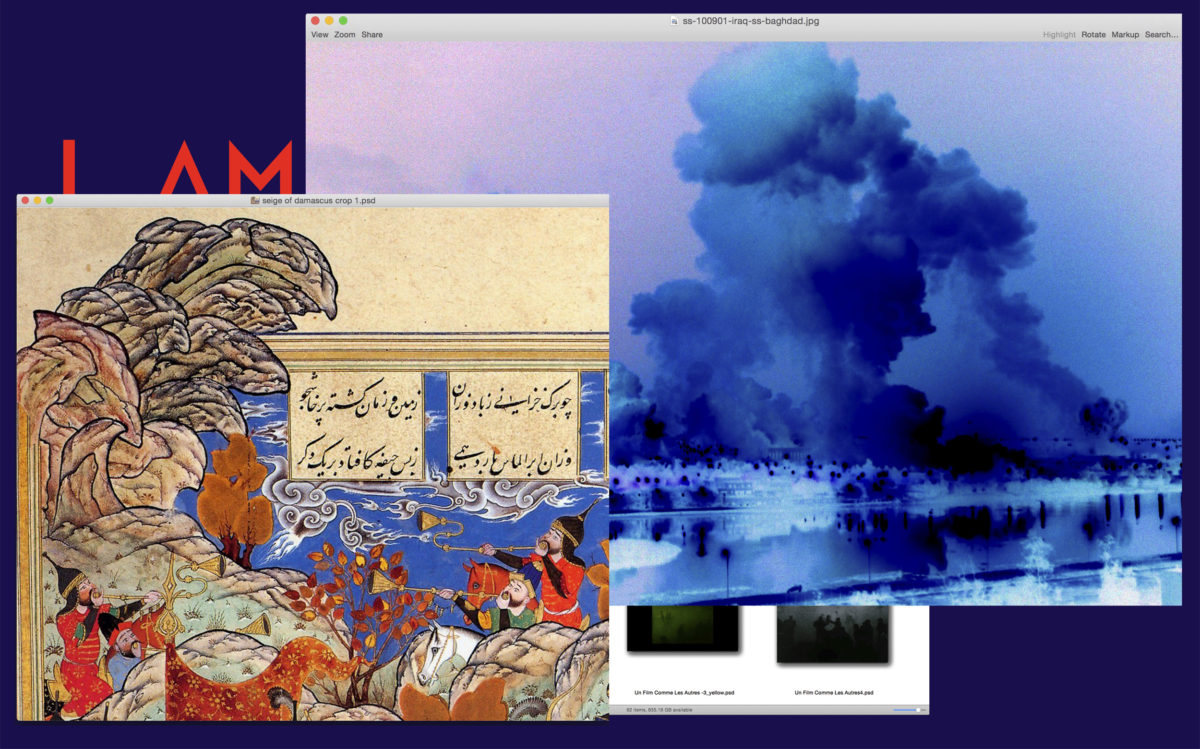

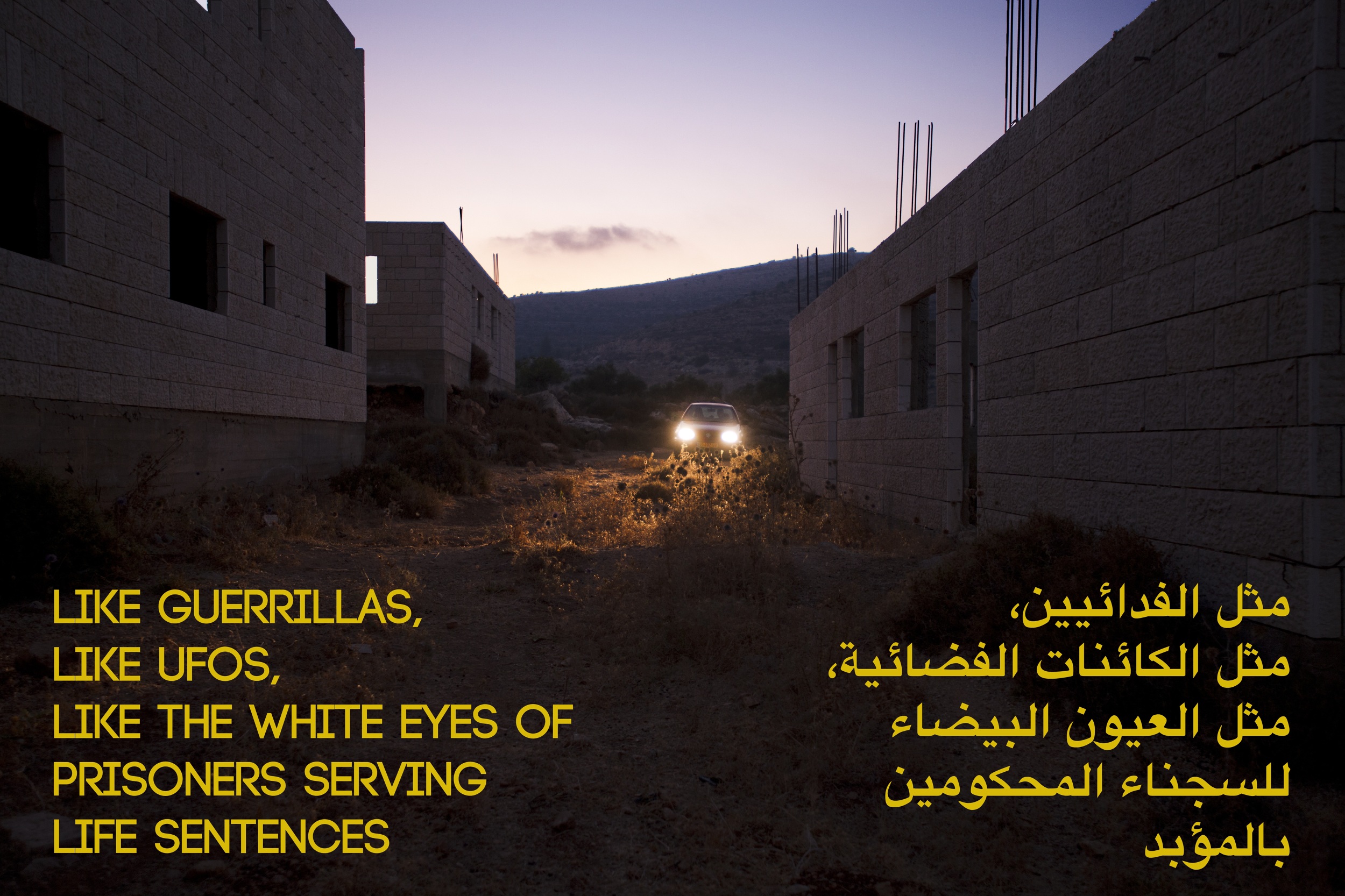

- Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou Rahme, Screenshots, 2014 to present. Courtesy the artists

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou Rahme

The Palestinian romantic couple and artistic duo explore their divided heritage through immersive sound, image and video.

Basel Abbas

I grew up with music as my first creative impulse. I had a guitar at home, an accordion and a keyboard, and I remember recording tapes, splicing things up, taking machines apart. I first met Ruanne in Jerusalem when I was sixteen years old. I was a friend of her brother’s. Much later, we were both studying in London and that’s where we became friends. We started a relationship, and the work came after that. We never really decided to become an artist duo per-se, but we got invited to do something together, and then it just kept happening. We became a de facto duo.

There is an obsession with the ego of the artist, the individual genius. First of all, we were very aware of a collaboration as a political position, and of our status as a duo makes a statement on its own. It’s difficult to actually let go of your creative ego, to put it bluntly. You need to learn how to let go of it as an artist. We worked very hard to teach each other about the skills we have early on. She taught me how to use a camera and edit video, and I taught her how to use a synthesiser.

“There is an obsession with the ego of the artist, the individual genius”

We’re very hands-on with our own production. We compose our own sound; we print our own images; we edit our own footage. We also collaborate with others. Even when you’re two people you can become quite insular, so it was quite important to maintain that collaborative process outside of our own partnership.

Finishing a project can be quite painful because you’re questioning everything all the time. We are very critical about our own practice, and about practice in general, and with two people you’re coming at it from many angles. We’re two humans, and there has to be some awareness that both people have their ups and downs. But then there’s a richness that you feel in the outcome because of those two minds.

It’s important to be aware that the person who you’re collaborating with is just like you. You need to allow space for the other person and respect the differences in the way people work. A good collaborator for me is someone who has awareness of their own ego, and of other people’s feelings, and who is able to negotiate and navigate with them.

Ruanne Abou Rahme

Our work is focused on ideas and issues that we’re passionate about, and so it becomes hard to distinguish between art and life. Like, are we having a conversation about this, or are we going back into work mode? You can very quickly go into talking about details of a project, or emails that you have to do. Even as a solo artist it’s hard to untangle where things end and where things begin. It’s a challenge, but we continue working together because it’s also a pleasure. The synergy is really exciting.

I grew up in Jerusalem. My first clear memories were of being part of the First Intifada, the uprising against Israel. I used to visit a girls’ orphanage near my house, and I also went to a children’s theatre. That was all during the time of soldiers on the street—very intense experiences.

There were no exhibitions, so the art I encountered was mostly through my father, who was a publisher of independent books. It was a very particular atmosphere to grow up in. There were also popular forms of song and dance, but visual art was in political posters and through books. I think that whole period really shaped me and shaped my work, and my trajectory.

“Collaboration is a humbling thing, and incredibly powerful. You’re much more permeable”

When you have two very different perspectives on particular aspects of the work, at first it’s just headbutting with the other person, but then you have to come up with a third way. There’s all that negotiation, and artists have egos. You can do something that you think is really working, and then the other person doesn’t think it’s that great.

The most rewarding thing is when you are able to synthesize something into a result that you could not have got to by yourself. Collaboration is a humbling thing, and incredibly powerful. You’re much more permeable.

I think you always have to respect the person that you’re working with and be open to other perspectives and ways of doing things. A true collaboration is about equality. We both do everything, and it’s very much about us creating something together. Of course, it’s easier said than done, and there will be arguments when you disagree. You constantly work towards all these qualities. It’s about mutual respect and a shared vision.

As told to Louise Benson

This article first appeared in Elephant issue #43, summer 2020

BUY NOW