The worst age to be a woman is forty-four. That’s according to studies in the US and the UK, at least. Why? Midlife, generally considered to be the time we hit our forties, is reported to be the bottom of a U shape of happiness, as women reach the menopause and things generally start going south—physically and psychologically. As women we are repeatedly told to expect to disappear, until we are fully released from the demand to be sexual.

Feminine identity has a particular relationship with age. The feminine ideal we’re exposed to perennially in society is one of preternatural youthfulness. Even when ads and films portray older women, they tend to be those who have “aged well”—a genetic miracle. Looking good for your age means looking younger than you are. But the women we see in their midlife in visual culture are usually the exceptions, not the norm.

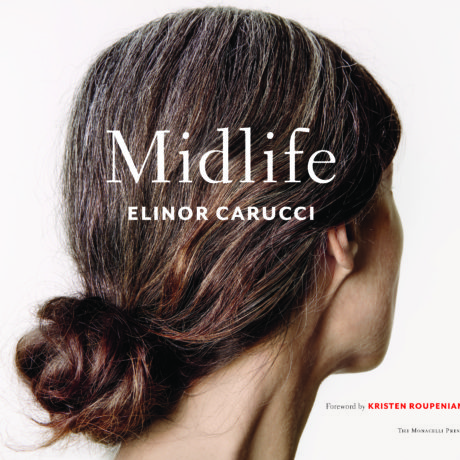

I feel in some ways as if I’ve watched the artist Elinor Carucci’s journey to midlife from afar, from her late-1990s monograph Closer (covering the first years of her relationship with her partner Eran and her own parents in their midlife) to Mother (an extended portrait of her life as a new and young mother; images of how brutal, all-consuming and tender it can be). Now she has released a continuation of her self-portrait in the form of a new photo book, Midlife, which is a document of life in her forties. Here, she once again turns the gaze that she used in the previous decade—harsh and forgiving at the same time—onto herself. the lighting she chooses doesn’t flatter flaws, and gives her images an almost theatrical look, a chiaroscuro effect, throwing into stark relief the parts we might usually try to tone down or avoid looking at for too long or too close.

“Having my uterus taken out of me was a catalyst for a sudden, overwhelming sense of loss”

Her examination of her own image—her body, her face, her family, her sexuality—is candid and unflinching. There is often a concern for the physical in Carucci’s work. She has previously looked at pain, comfort and strength, and in Midlife she appears topless; sweating; with facial hair; grey hair; strung out and stretched out; with no top on. At times, her lens is almost medical. There is a picture of her uterus, laid out on a blue cloth, after a 2015 hysterectomy. “Having my uterus taken out of me was a catalyst for a sudden, overwhelming sense of loss, not only because of losing this physical part of me but of something more: the definite end of my fertility. It felt like the final loss of youth. Everything seemed different, like my life was a building and I suddenly moved one floor up, or was it down, and that I wanted to run back to the previous floor but never could again,” she recounts in her own text.

Carucci zooms in on her skin, aged forty-six, in almost microscopic detail. There are blood paintings she began making and photographing in 2012. She flings us into the excruciating truth and detail, the signs of ageing that in women “are treated as though they ought to be invisible,” Kristen Roupenian—author of the viral New Yorker short story, Cat Person—writes in the foreword that introduces Carucci’s images.

There is an intimate portrait of the artist and Eran that recalls a 2002 picture of the two, And If I Don’t Get Enough Attention. The sofa is different, and the perspective is too: this time, Carucci appears more vulnerable, protected, gazing off into the distance, held by her partner, who has also changed with the years. In the earlier portrait, he appears to be asleep. There is also a portrait of a naked Carucci hugging her son tightly, and in another, her mother looks on in the kitchen as her grandson clings naked to the artist. She questions if this is appropriate—she titled the 2016 portrait Can I Still Hug My Son Naked. It is a challenge and a question not to the world but to herself, a poignant stage in her experience as a mother as her children become independent and more detached from her.

“Being inclusive shouldn’t only mean including positive stories”

It was a photograph of Carucci’s that originally illustrated Roupenian’s Cat Person: a close-up of a hirsute man with ginger-tinted stubble, open-mouthed learning in to kiss a young woman. As Roupenian pointed out, the photograph was so perfect for her story because it had the same measure of ambivalence and the same disquieting effect as her narrative had on people’s imaginations, so that we are never sure who is at fault or who has the power—in fact, those questions are displaced.

Often, the images that we see in art and culture that promote diversity give everything a glossy veneer—suggesting that everything is going to be ok. But being inclusive shouldn’t only mean including positive stories. We need complicated images with complex meanings, things that are difficult to untie. In an Insta-perfected world, we also need to see the average, the banal, the everyday of existence: images of Carucci at home in “house clothes”, with a glass of wine at the end of day, paying bills with her husband, are refreshing to see. Moving from page to page, Carucci’s narrative touches on it all.

There’s one image that does seem to sum Midlife up—though this isn’t a pointed decision by the artist. The photograph is another close-up, of two pubic hairs. One is dark, one is grey. They combination reveals a body in transition, moving inevitably forward and looking instinctively back, past and future together in the present.