“Because it’s in my nature; because it’s against nature; because it’s nasty; because it’s fun; because it flies in the face of all that’s normal, because I’m not normal,” the late performance artist Bob Flanagan wrote in his highly-charged, intensely emotive poem of 1985, Why. Flanagan suffered Cystic Fibrosis, and died aged forty-three, in 1996. In part a personal account of his own sexuality, the poem is arranged as an explanation, addressed to everyone, including the artist himself, an account of all the experiences that have shaped him: from Catholicism to childhood bullying and sickness. After reading Why, works like Flanagan’s first 1989 performance Nailed, in which he nailed his penis and balls to a board while singing If I Had a Hammer, by The Weavers, are far more relatable to the “normal” viewer.

An extract of Flanagan’s Why is reproduced in a text on the artist—together with a photograph of Bob on Scaffold, a 1989 work in which the artist uses an elaborate torture machine—in Art and Queer Culture, by Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer, a lesbian art critic and a gay art historian who do not always agree. Their book was first published in 2013, but this month, Phaidon releases a newly updated edition, still “forged through both dialogue and (occasional) disagreement”, as Meyer puts it. A whopping overview of artists from 1885 to the present, their survey embraces “the play of difference, debate and dispute” in the exchange between sexuality, art and identity, calling to mind two core commonalities in so-called queer art; the confrontation between fear and fantasy, as visualized perfectly in the slogan of the 1970s gay liberation movement.

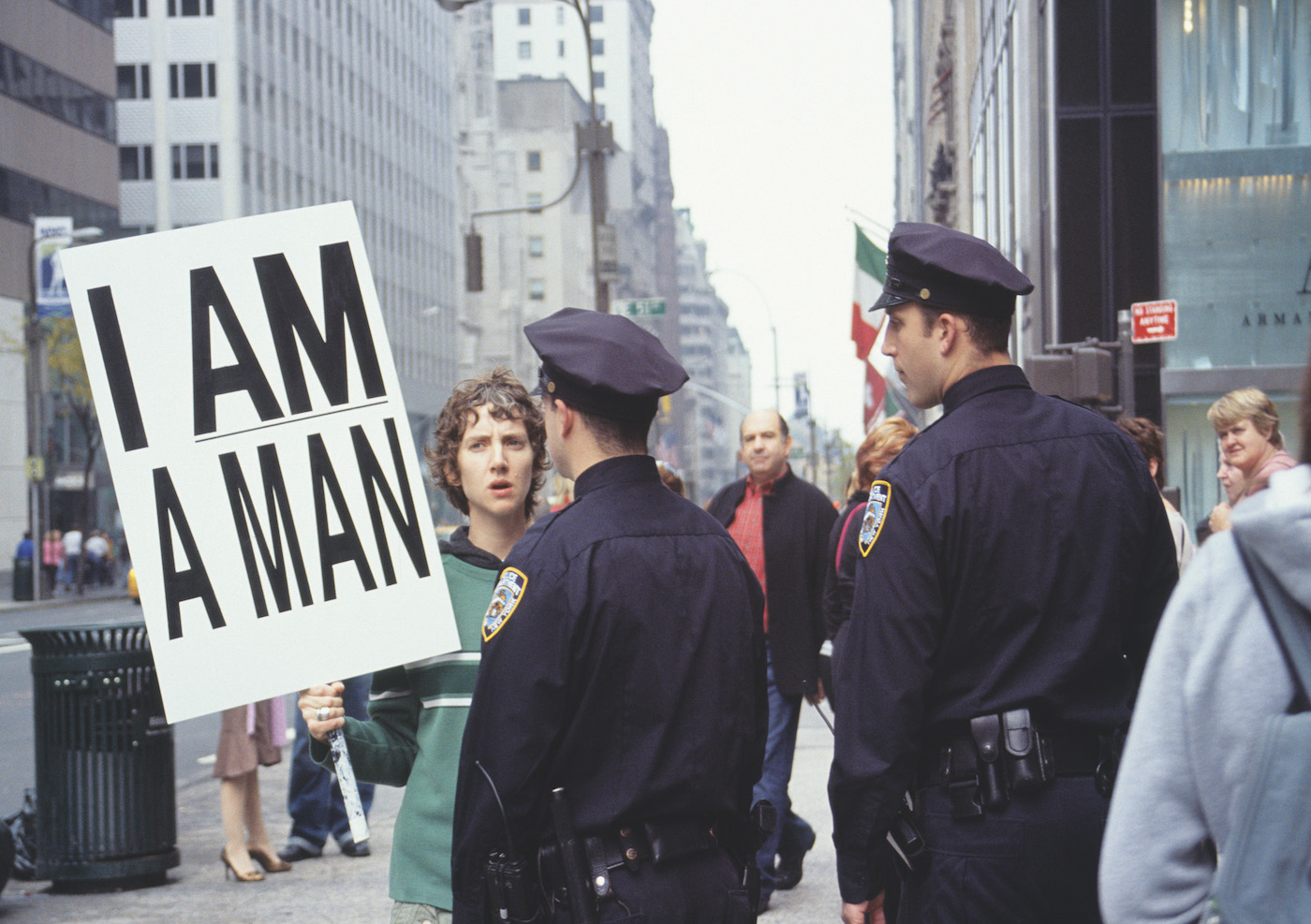

As Flanagan’s work demonstrates, fear and fantasy often coexist in queer art. The decision to include Why also emphasizes the fundamental importance of authorship when it comes to sexuality, something that is consistent throughout the book. Both Lord and Meyer’s own identities and practices form part of this book; one that seeks solidarity within the queer community and traces a shared history but that doesn’t try to represent everyone’s interests as aligned. “We have chosen the term ‘queer’ in the knowledge that no single word can accommodate the sheer expanse of cultural practices that oppose normative heterosexuality,” Meyer writes an introductory essay on the first chunk of history, up to the end of the 1970s, which Lord picks up in a separate essay, Inside the Body Politic. The rest of the book is entirely dedicated to the artists, their works, documents and texts.

A lot has changed in the six short years since Art & Queer Culture was first released, especially in terms of visibility for LGBTQI art; though in wider culture, there is still debate to be had about who makes the art and how we view it. The most recent example is the Belgian director Lukas Dhont’s new film, Girl

, which came under fire from critics, including Oliver Whitney, for using cis actors. Whitney referred on Twitter to the “the lack of trans voices in the critical conversation”, around the film. Jill Soloway’s series, Transparent, has faced similar criticisms for casting Jeffrey Tambor, a white cis male, in the role of a transwoman. Sebastian Leilo’s 2017 feature A Fantastic Woman, starring Chilean actress Daniela Vega, is one of few breakthrough features to have cast a transwoman in the lead role.

The cis gaze is still problematic on the screen and in the mainstream, and in visual arts, it is no different. What Lord and Meyer suggest is that the issue emerges from the lack of critical dialogue and the institutional sidelining when it comes to any art that is made “to oppose the tyranny of ‘the normal”. This book reclaims that space, and shows how rich and varied this history has been. With the increased visibility for queer art and culture now—as debates around films like Girl prove—there is a greater need to understand all the work that has been done to get to here, and why representation matters. There are phenomenally famous artists here, and artists who have not been recognized; there are artists who kept their sexuality hidden, or subtly sequestered in their art, and others, Flanagan just one of many, who were unambiguous and direct. There are also artworks that only queer history has paid attention to: such as Jasper Johns 1955 Target with Plaster Casts

, a painting with a plaster cast of a penis that was considered too provocative to purchase for the MoMA collection.

The artists Lord and Meyer arrange in their “unruly history” worked in very varied social and political contexts over the last century, between times when homosexuality has been illegal (and remains so in parts of the world); the trauma of hate and violence ripple through the pages. But what these artists all share, if nothing else, is the courage to tell their stories as they wanted; to make art, no matter what. As Minor White, photographer, editor and co-founder of Aperture, included in the book, writes: “Privacy is a choice; it’s about living your life the way you want to. Secrecy is usually a form of protection, but the safety it affords has the same relationship to freedom as being locked in an isolation chamber.”

Art & Queer Culture By Catherine Lord and Richard Meyer is published by Phaidon

BUY NOW