Monaco’s beach-front promenade stretches along much of the principality’s coastline, interrupted by luxury beach clubs, rocky cliff edges, private villas, the occasional drained pool and, for the last few years, construction boards depicting a photographic render of the horizon line they obscure. It seems to be a year-round festival of construction and Formula 1 prep. In a country with more billionaires per capita than anywhere else in the world, Monte Carlo’s lap of luxury is draped in elaborately decorated hoardings, wire mesh fencing, overlapping Belle Époque villas and peach-tinted skyscrapers; as well as the obligatory palm trees, gold-plating and jardins exotiques.

Navigating Monte Carlo on foot, between the Grimaldi Forum, where artmonte-carlo is held, the National Museum’s Villa Paloma and Villa Sauber, and the art fair’s various satellite events, is like being in an arcade game won by dodging Ferraris, locating hidden staircases, crossing world-famous hairpin bends, and counting the number of bedazzled, bouffant-ed, stiletto-ed women ambling along the sides of A-roads. It’s difficult to ground yourself in any sense of recognition, or reality, when even the high-gloss landscape is part simulation.

The fair itself mirrors this atmosphere of Riviera gloss, ornament and pastel excess, playing on the absurdity while existing within it and, in certain instances, utilizing its own visual language to critique it. Genova gallery Pinksummer’s exhibition of works by Invernomuto—a collaboration between Simone Bertuzzi and Simone Trabucchi—was focused on Italian colonialism and, in particular, Mussolini’s invasion of Ethiopia. It’s Invernomuto’s second project focused on the Mediterranean, the first being Black Med, which was exhibited at Manifesta 12, Palermo, and “explore[d] different journeys of sound movement, touching topics such as alternate use of technology, migrations, peripheries and interspecies”, rooted in Alessandra Di Maio’s adaption of black Atlantic theory to the Med.

MED T-1000 has the (knowing) feel of a Mediterranean, glass-fronted estate agent, with ceramic heads, a giant white rug, vending machine, photographs and postcards depicting bright blue skies and lush landscapes. On closer look, the ceramic heads are actually Moor’s Heads, turned into robots with laser eyes and the mass of picture-postcards is being “harassed” by a T-800 cyborg from the first Terminator film. The vending machine is dispensing water in plastic bottles labelled “Mediterranean Sea Water Not Suitable for Drinking” (a limitless edition by the artists) and has a still from Invernomuto’s film Negus—a documentary starring Lee “Scratch” Perry, which “explores the convergence of history, myth and magic through the complex and competing legacies of Ethiopia’s last explorer Haile Selasie I”—printed on its plexiglass front, and the carpet depicts a technical drawing of Selassié’s last visit to Italy in 1970. The installation is playful in its approach, and effective in presenting the Mediterranean sea as “the battleground for increasingly complex identities”: “once understood as a fluid entity aiding the formation of networks and exchange, [it’s] now the scenario of a humanitarian crisis and heated geopolitical dispute”.

“In a country with more billionaires per capita than anywhere else in the world, Monte Carlo’s lap of luxury is draped in elaborately decorated hoardings”

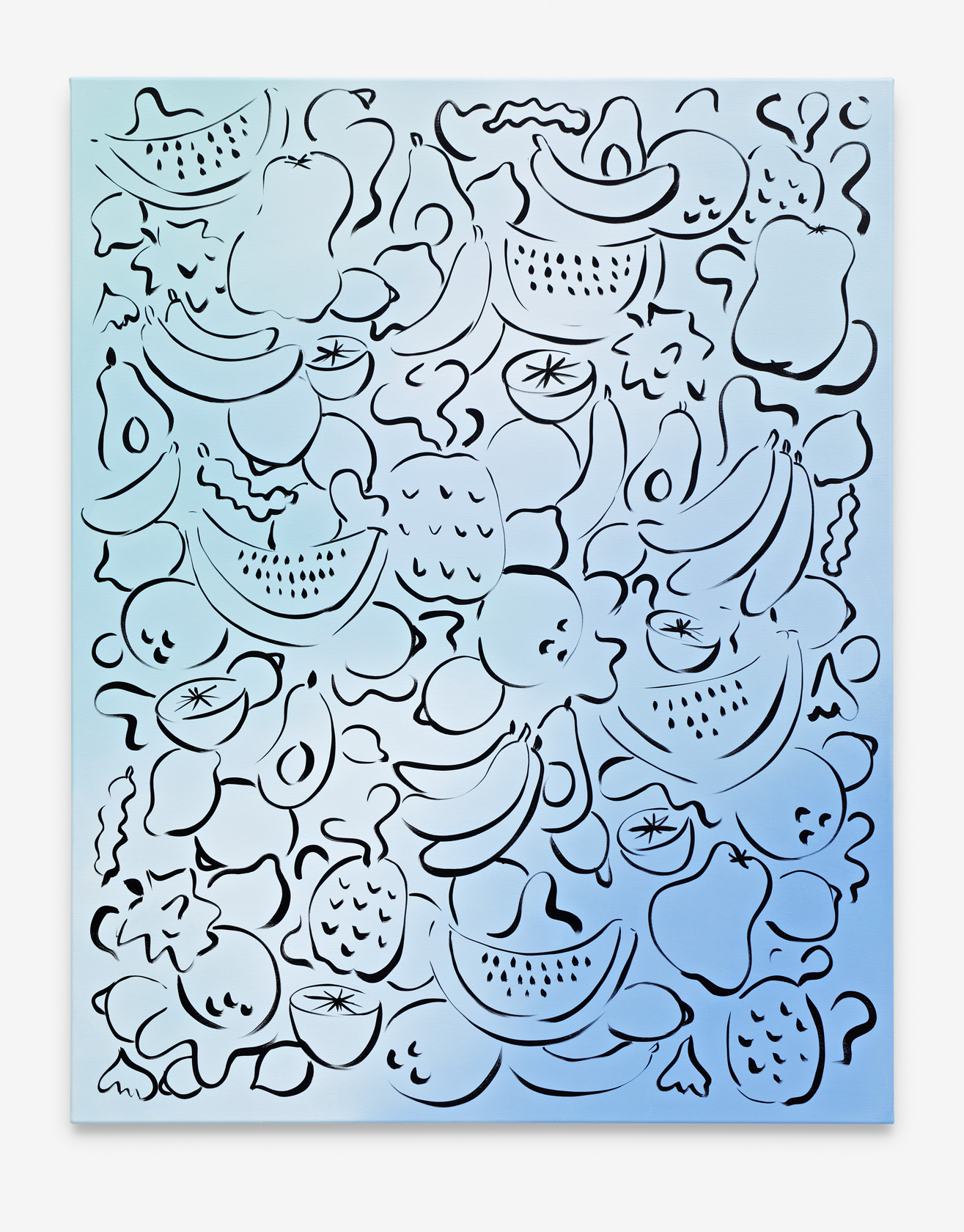

- Left: Sol Calero, Frutas friestail 6, 2018. Acrylic and oil stick on canvas 170 × 150cm; Right: Ad Minoliti, Untitled (Logos 2), 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 150 × 150 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Crèvecœur, Paris

Paris- and Marseille-based gallery Crèvecoeur showed works by a mix of practitioners working between textiles, sculpture, photography and painting, including two South American artists, Ad Minoliti and Sol Calero, from Argentina and Venezuela respectively. Minoliti’s work, Untitled (Logos 2), draws upon early modernist iconography, and like Invernomuto’s pieces it seems at first to be light and decorative, while tackling complex ideas around techno-feminism, queer theory, geometry, space travel and colonialism. Minoliti’s work is concerned with intersectionality in terms of both its core themes and use of disciplines—its radical politics told through light-hearted, colourful exuberance.

Similarly, Sol Calero’s work, often taking the form of brightly painted, immersive installations, can be considered social practice in its broadest sense—both in terms of engaging with political issues, and a want to engage her audience directly with and in the work. Calero’s projects can be informed by everything from hyperinflation to how salsa music reflects identity, interested in reflecting on the ambiguity of cultural signifiers, and how meanings can proliferate and change. She’s particularly drawn upon the popularization of Carmen Miranda, and the appropriation of Latin American culture by the USA in the mid-twentieth century; taking recognized and re-appropriated cultural codes and putting them back into context. In her series of Frutas paintings, Calero roots her work in the visual language of 1930s Latin America, focusing on lines, shapes and bold colours; in a study of the mis-appropriation of Carmen Miranda, who was seen to represent “the exotic beauty of Latin America”, when the context of her costume was based on clothing worn by Afro-Brazilian Baiana women who made their living selling fruit.

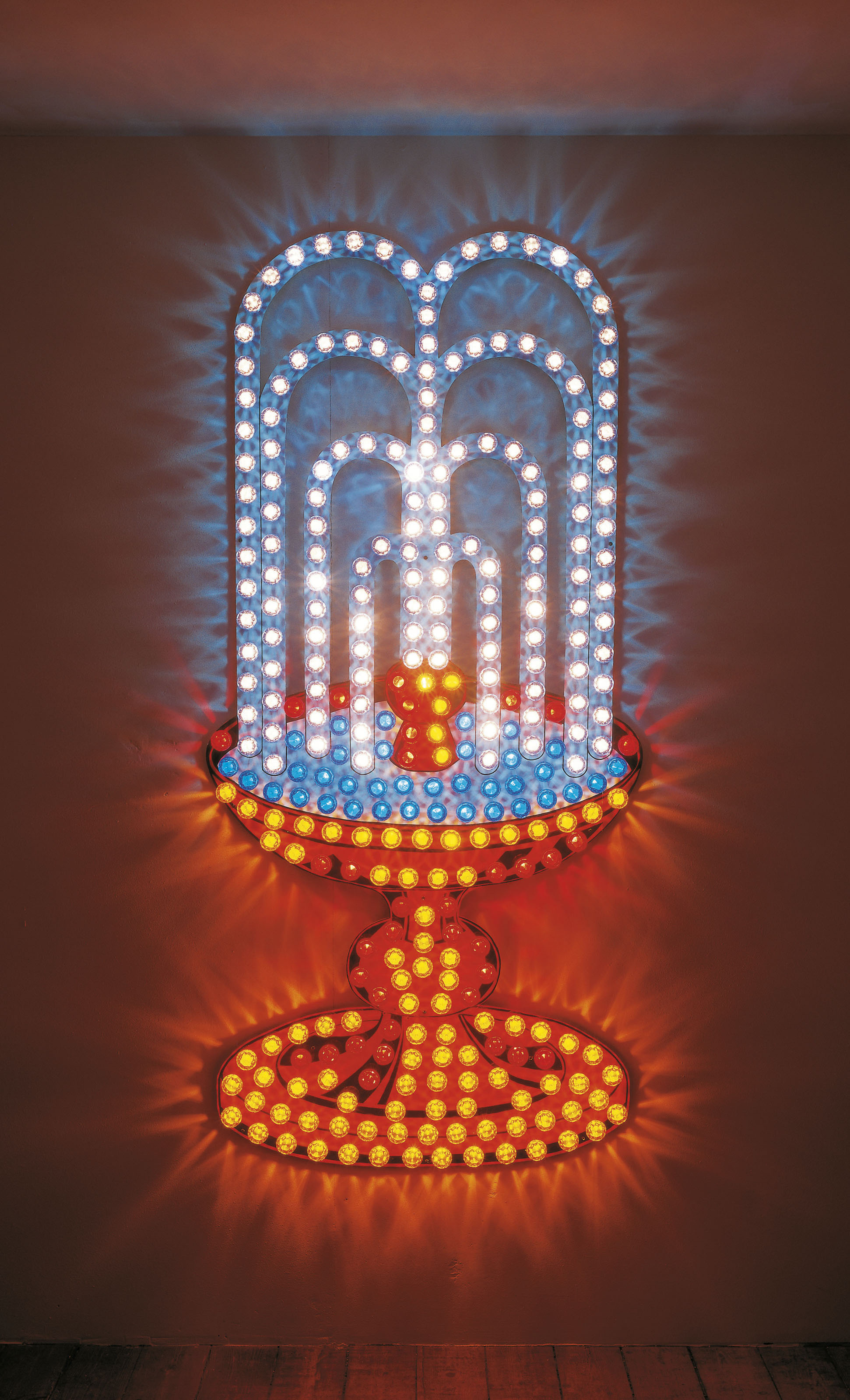

“The title, and the work itself—a dazzlingly absorbing and perpetual fountain in lights—immediately conjures up visions of the Las Vegas strip”

Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s Excessive Sensual Indulgence, exhibited by Blain Southern, also typifies this potential for misunderstanding. The title, and the work itself—a dazzlingly absorbing and perpetual fountain in lights—immediately conjures up visions of the Las Vegas strip, but the work was apparently made more with Blackpool in mind; in particular, its illuminations, the carnivalesque annual event founded in 1879, which sees out the ending of the seaside resort’s season.

Torino-based Galleria Franco Noero showed Francesco Vezzoli’s People People (Fighting Sexism with New Tactics – America Loves Her Again), two framed covers of People magazine side-by-side, one of Gloria Steinem, the other of Jane Fonda, each embroidered with tears in his signature needlepoint technique. It seemed to be Vezzoli’s only work at the fair, which is surprising considering how the whole of Monaco could so easily pass as an elaborate, site-specific Vezzoli performance; his core concerns being power and seduction in contemporary culture, and the ambiguity of what constitutes truth.