I’ve had very few brushes with fame. As such, I’ve been dining out on the fact that Craig off series one of Big Brother may or may not have winked at me as he ran past during the London marathon. For all the reality TV guff that has come since then, and the genre’s numerous problematic elements which we’ll go into later, there’s no doubt that the first series of Big Brother was a watershed moment when it came to television. It was the talk of our secondary school (and undoubtedly every other), as well as every office, home, and rival channel’s commissioning meetings.

Big Brother really did change everything. For the first time, we invested time and engagement in people who were ultimately quite dull, not unlike people you know, just on the telly, nigh on constantly. And while we’re all aware that these shows are heavily edited, the premise at least was that there’s no escape; even the showers weren’t out of bounds when it came to the menacingly rotating cameras in every corner of that house.

No longer did we need “national treasures”, or indeed any discernible talent for our TV stars. Nope, we wanted lesbian nuns and cheats-turned-removal-drivers (fact: a very good friend’s brother worked for Nasty Nick’s removals company in Australia just a couple of years ago).

“Even the showers weren’t out of bounds when it came to the menacingly rotating cameras in every corner of that house”

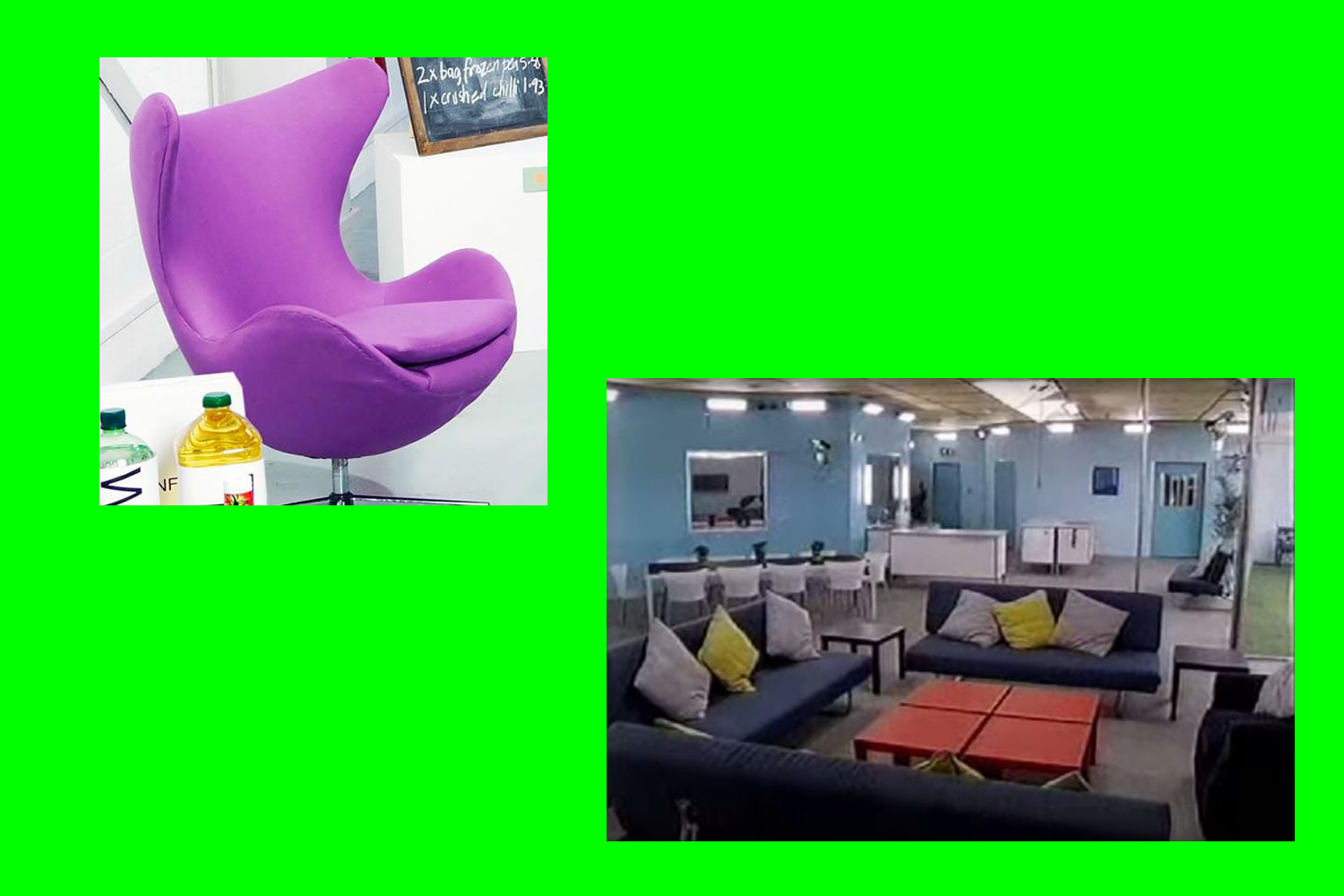

Since the contestants had literally nowhere to go but the house, it also made us look at interiors in a new way. The layout of the house was no accident; architecture, after all, has a huge impact on human behaviour. The famous diary room chair was none other than the Egg chair designed by Arne Jacobsen in 1958 for the Radisson SAS hotel in Copenhagen, manufactured by Republic of Fritz Hansen. A modernist classic for the show that epitomises postmodernism eating its own tail. But despite that Jacobsen chair, the set’s block colour, geometric-shaped furniture and carefully plumped cushions in mustard and grey screamed “We just discovered IKEA; Have you?” Then, of course, there was the hot tub, a rippling pool for the show’s preening narcissuses to fall into and, on occasion, lose a little dignity. Even the chickens were carefully chosen clucking props: you can tell a lot about a person by how they interact with animals.

- Big Brother series 1 screenshot

Though the first series came out in 2000, so much about BB’s first series feels so very nineties. There’s Craig—who ultimately went on to win—acting as the proxy for the ubiquitous dude with the big muscles holding a cute chubby baby on almost all posters sold in nineties high-treet mecca Athena. There’s the loudmouth but likeable skinhead girl; the Page 3 blonde; the “greed is good” hangover from the eighties and the pumping Big Club Anthem title music by, naturally, Paul Oakenfold. The graphics predicted their own mimicry twenty years on, that glitchy “ooooh, they’re watching you” disintegrating VHS thing.

The format, too, was undoubtedly revolutionary, and has since been mimicked time and time again, largely with diminishing returns. I personally make an exception for The Circle, another Channel Four show not unlike Big Brother, in which contestants are housed in their own self-contained flats; they interact only through video screens, thus enabling them to pretend to be whoever they want to be.

While the format naturally waned in interest over time, it was a show that united the nation and was perfect gossip and tabloid fodder. Until recently, people seemed to lament the lack of “water cooler” TV. The argument was that telly that galvanized us all died with the rise of streaming services, and the decline in people watching actual television sets in real time. There we were us millennials, selfishly watching things whenever we wanted, louchely scrolling through Mubi when not messing about with experiential brunches. Then Love Island came along, and those same people bitched about people watching Love Island instead.

Such reality shows have the power to galvanize all of human life into one squalling, bitching mess of emotion, lust and hatred. The caricatured fame-seekers offer us the acceptable face of downright rudeness and judgement. These people put themselves there to be scrutinized, right? So in scrutinizing, we’re just doing what we’re not-so-subtly told by those smart editors and producers.

- Big Brother series 1 screenshot

There are a lot of things wrong with such shows of course. It’s hard to forget the blatant racism in 2007’s Celebrity Big Brother, when a number of contestants continually made remarks around contestant Shilpa Shetty—most notably the late Jade Goody’s reference to the Indian actress and former model as “Shilpa Poppadom” and Danielle Lloyd’s “fuck off home” remark. By the end of the series, Ofcom had received “just over” 44,500 complaints about racism on the show.

In recent times especially, mental health concerns around such shows have become bleakly apparent for both those appearing in them and those watching them. Jo O’Meara and Goody were both treated for mental health issues after leaving the Big Brother house in 2007. A piece by the Guardian recently reported that The Mental Health Foundation was concerned about the impact such shows have on younger viewers, stating that a quarter of people aged 18-24 said in a survey that reality TV makes them worry about their body image. Two people are believed to have committed suicide after going on Love Island, as well as the show’s ex-presenter, Caroline Flack.

In 2020 there’s little room for Big Brother. An entire generation has passed, and it’s a different world for those in secondary school now. Big Brother has long been relegated to Channel 5, and seems like a relic of simpler times, before ubiquitous lip fillers, hashtags, influencers and online trolls. Big Brother is a thing of the past.

“Today, we’re collectively making ourselves the stars of our own reality broadcasts”

After all, today we are constantly surveyed by the big brother of big data (“accept cookies” for an easy life; “save password for this site”). To boot, we’re collectively making ourselves the stars of our own reality broadcasts without the need for Endemol producers or rounds of audition processes. We pimp, preen and post our Instagram stories, create YouTube channels, livestream the minutiae of our gaming on Twitch and our sex lives on Chaturbate. The big difference is that now we are the editors—no one’s there to twist the narrative for the ultimate good-cop-bad-cop storyline sucker punch.