“If there is a theme to this themeless show,” Ward notes, “the idea is that some of the works really do transcend time. They relate back to history as much as they do to the present.”

Everything At Once brings together forty-five works by twenty-four Lisson artists at Store Studio on the Strand (presented in partnership with the Vinyl Factory), including classics such as Tony Cragg’s sculptural spires made from rubber, stone, wood and metal detritus, Minster (1985) and Anish Kapoor’s gigantic bell-like installation from 1998 At the Edge of the World II, which hovers above the viewer as if to swallow them up within its mute red recess. Testament to their timelessness is the fact that these works fit seamlessly with more recent pieces such as Cory Arcangel’s blithely sinister projections from a hacked video game MIG 29 Soviet Fighter Plane and Clouds (2005) and Ryan Gander’s sculptures of armatures adopting expressive human poses, including two as Mary holding Jesus in a surreal, robotic recreation of the Pietà.

“The visitor must leave any expectations of tightly curated thematic coherence at the door.”

Everything At Once declares itself to be “neither a chronological nor encyclopedic history” of the gallery’s exhibitions but rather an “interconnected journey” exploring experience, effect, and event. And indeed the visitor must leave any expectations of tightly curated thematic coherence at the door because the show meanders delightfully through works that sometimes seem to have little obvious link, such as a glass and steel pavilion by Dan Graham placed near sculptures of a tree root and trunk by Ai Wei Wei and his 60m wallpaper frieze depicting the displacement of people from ancient to contemporary times.

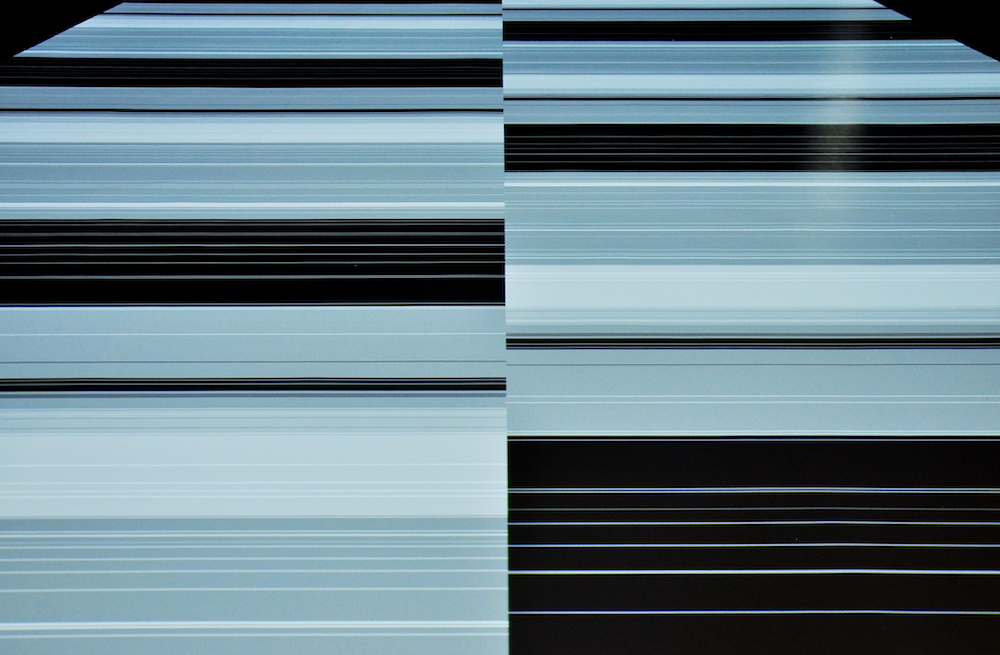

These are among several “important sculptural statements” found on the ground floor. On the first floor, older works are juxtaposed with the very new, among them a series of vibrant paintings by Stanley Whitney in brightly-coloured grids that appear to pulsate and a monumental mural by Richard Long, painted this past Sunday with mud from the River Avon. The top floor is given over to works that fuse diverse languages and voices, some along existential lines. In Susan Hiller’s mesmerising installation Channels (2013), for instance, disembodied voices recount individual “near-death” experiences in a darkened room but for an eerie bank of television monitors, highlighting the gaps in scientific understanding of such phenomena, while Tatsuo Miyajima’s Time Waterfall, created this year, presents a hi-tech column of randomly cascading numbers from one to nine, avoiding the deathly void of zero in a monument to life and perpetual renewal. Another standout is Wael Shawky’s final film in his trilogy of Egyptian parables Al Araba Al Madonna, which makes its London debut here. Produced in negative, with child actors whose speech is dubbed with adult voices, the film estranges and enchants as it weaves together myth, metaphysics, superstition, and history into a richly poetic whole.

This exhibition demonstrates Lisson founder Nicholas Logsdail’s extraordinary eye for talent, which has remained constant since he opened the gallery on Bell Street in 1967. Logsdail began pioneering Minimal and Conceptual artists such as Daniel Buren, Sol LeWitt and Richard Long and in the 1980s gained acclaim for championing British sculptors such as Richard Deacon, Kapoor and Cragg. In the past ten years or so he has taken on rising stars such as Gander, Nathalie Djurberg & Hans Berg, Haroon Mirza, Wael Shawky and most recently, Laure Prouvost.

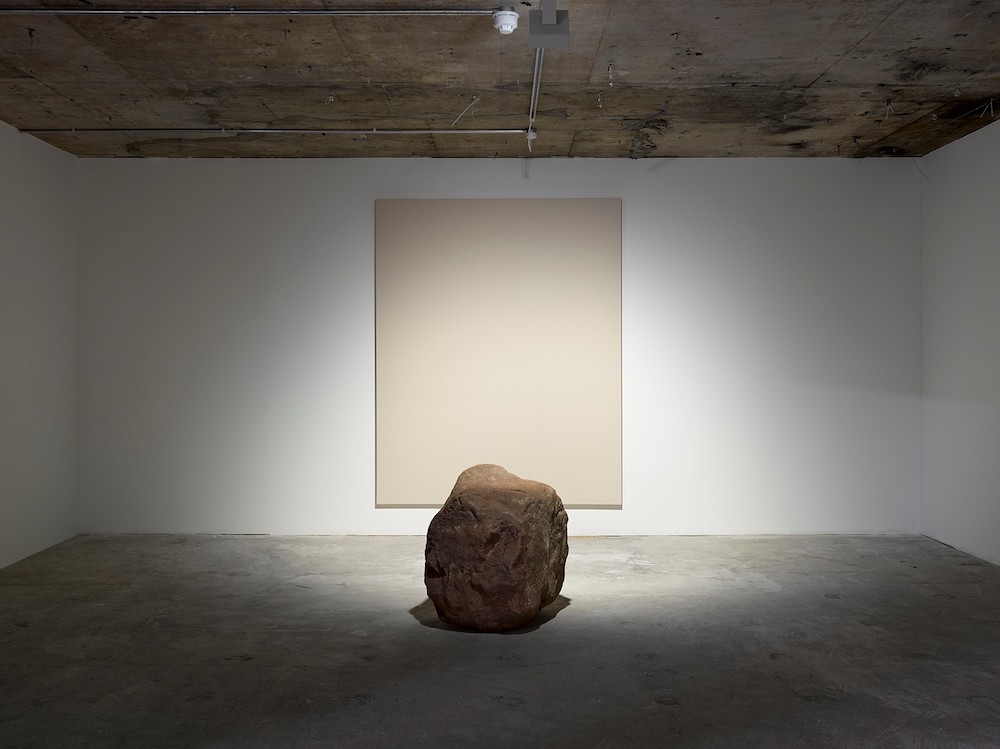

The works in this show share an underlying integrity that makes them immune from the notoriously fickle fashions of the art world. Several are profoundly contemplative. Lee Ufan’s raw stone facing a blank canvas, Dialogue – Silence (2013) is displayed in a dimly lit chamber opposite a multi-layered brush-stroke on the wall; Shirazeh Houshiary’s compelling 2003 installation Breath envelops the visitor in simultaneous chanting of Buddhist, Christian, Islamic and Jewish prayers as the vocalists’ breath is captured in delicate animations on four video projections. The world would benefit if versions of this work were placed in global trouble spots.

Heading up and out of the Lisson exhibition, a new departure is the use of the roof at The Store. The climb to the top rewards the viewer with both an amazing view of the London skyline and Arthur Jafa’s 2016 video work Love is the Message, the Message is Death, splicing found footage of Los Angeles riots, civil rights protests, sporting events and numerous arrests of black people to create a snapshot of African-American life in the twenty-first century. One of the most heartbreaking moments is a clip of police forcing a mother and her young children out of her car on a night-lit highway.

“It was an unending stream, a flood, a tsunami of police malfeasance.”

The police murder of seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2012 was the tipping point, Jafa told me, that prompted him to string together various sequences of footage he had stored up to make the film. “It was an unending stream, a flood, a tsunami of police malfeasance,” he said.

The Serpentine Gallery, which is co-presenting Jafa’s film at The Store with The Vinyl Factory, had wanted to include it in the artist’s recent show at the gallery, but Jafa refused, hoping instead to display it on council estates in predominantly poor black areas. “It was always intended as this nomadic black stealth thing, but London was like: ‘No’,” he said. Local councillors worried that it was “like stirring up a hornet’s nest”.

It was always going to be a challenge to follow up The Infinite Mix, the hugely successful audio-visual exhibition staged by The Vinyl Factory and Hayward Gallery last year, but Everything at Once has avoided trying to replicate its predecessor by encompassing a wider range of media. As with last year’s extravaganza, the brutalist architecture of the building plays a leading role.

“Again I think what we’ve managed to create is this unique experience of exploring a space and discovering artists that you may or may not know or thought you knew but you’ll see them in a new light, hopefully,” said Bidder.

Everything at Once

Until 10 December at Store Studio, 180 The Strand, London

lissongallery.com

You can read more about the Vinyl Factory in Elizabeth Fullerton’s article in Issue 32.