An eclectic crowd of young professionals, including corporate suit-and-tie types amidst the usual artsy crowd, gathered at the Guggenheim’s Frank Lloyd Wright-designed rotunda in New York this April to watch ballet dancers being tied up by professional S&M masters. A handful of male dancers hung from a cage-like structure, while girls mixed the gentle routines of classical dance with the sultriness of bondage, circling around the cage. “Ballet originated as a set of rules—an etiquette for bowing to King Louis XIV—and traces of this act of submission remain in the form,” muses multimedia artist Brendan Fernandes, who orchestrated the performance for the museum’s annual Young Collectors Council Gala. In doing so, he blended a practice more associated with underground gay culture than ballet within the hallowed walls of a traditional art institution.

Chicago-based Fernandes, who dropped out of ballet lessons after a childhood injury, has long been associated with the intersection of sadomasochism and ballet, two modes of performance radiating aesthetic pleasure at the expense of pain. “In S&M, queer bodies and queer communities use acts of submission and domination to experience new forms of agency and empowerment. In our current and complicated political moment, how might hybridized techniques bring about a new sense of agency or empowerment?” Fernandes, along with a group of queer artists, assume the manifestation of power and compliance embedded in S&M to dissect our precarious social and political dynamics. In doing so, they challenge a systematic effort by the authorities to limit self-governance through expression of consensual submission.

Fernandes, who coined the term “ballet kink” to define his hybrid of influences, was watching his dancers train months earlier this year, on a sunny January day by the coast of North Fork, Long Island. He was partaking in an artist residency, Uncommon Art at Sound View Hotel, overlooking a shore quite different than either the Guggenheim or an S&M club. The rehearsal at the refreshing Long Island seaside led to a performance at Central Synagogue, where the dancers dégagéd and twirled based on the artist’s signature kinky yet elegant moves.

“In S&M, queer bodies and queer communities use acts of submission and domination to experience new forms of agency and empowerment”

Meanwhile, the Kenyan-born artist is one of the standout stars of the 2019 Whitney Biennial with The Master and Form, another cage-like installation—a subtle riff on Modernist sculpture—activated by his team of dancers throughout the run of the show with his signature choreography of pain and pleasure. On the horizon for Fernandes is a solo September exhibition, titled Contract and Release, at the Isamu Noguchi Museum in Queens, where he will continue his take on Modernist sculpture with objects designed with inspiration from ballet training devices, the rocking chair Noguchi designed for Martha Graham’s Appalachian Spring and, again, S&M.

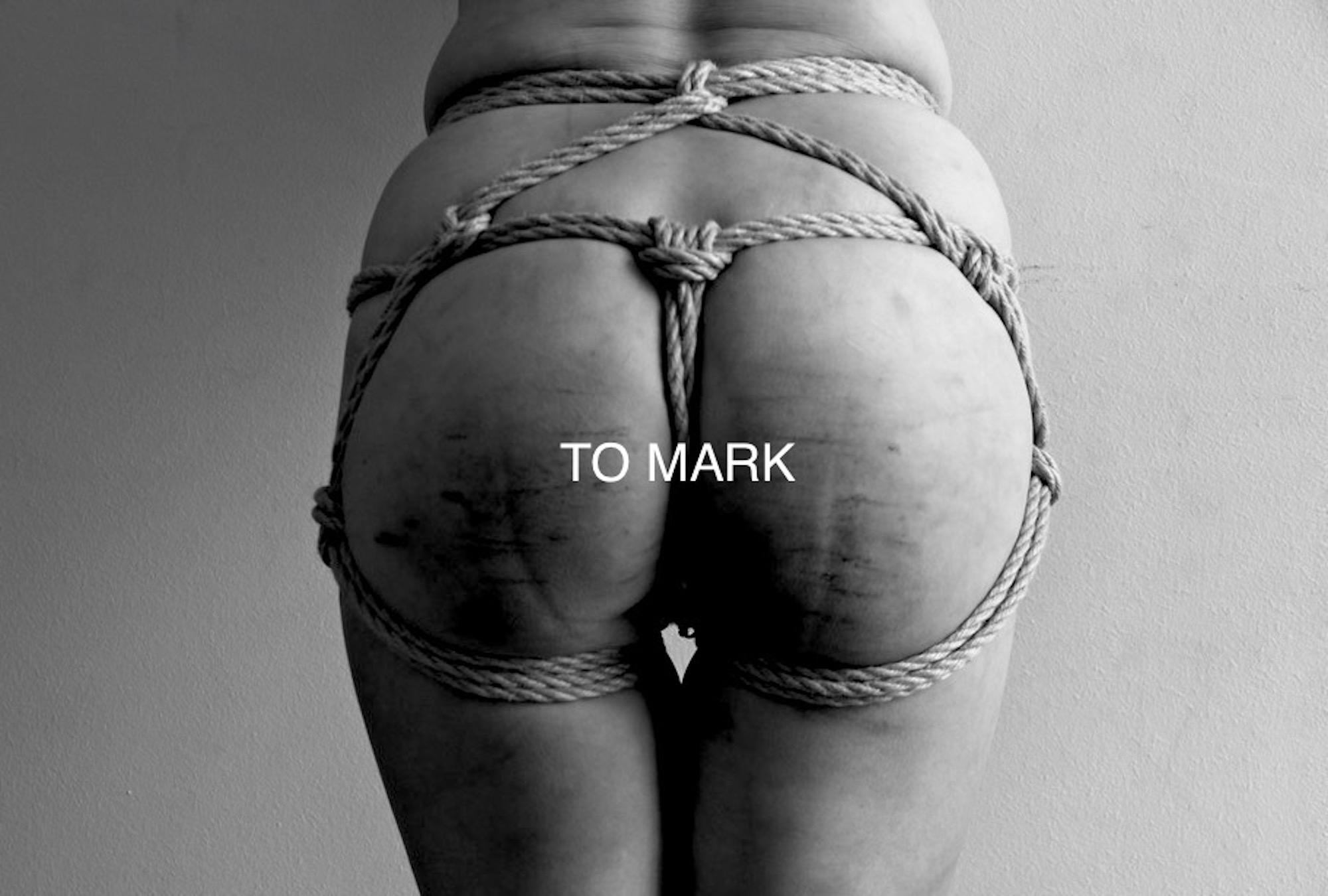

In May, curatorial platform SUBLIMATION hosted an two-hour-long performance to kick off artist Vincent Tiley’s solo exhibition, Scorpions, for his leather, rope and horse bit paintings tied in knots based on the Japanese bondage art of shibari. During the performance three performers, held together by custom-designed Chris Habana jewellery, remained still, enduring the pain of maintaining their bodies in positions dictated by the jewellery. The crowd observed the live endurance, in which one of the two performers conjoined by a ball gag started drooling half an hour into the performance, to the backdrop of paintings echoing the show’s exploration of the thin line between pain and pleasure.

Racial power dynamics and S&M have also spearheaded New York artist Carlos Motta’s recent P.P.O.W. Gallery exhibition Conatus, in which a twenty-four-minute film, titled Corpo Fechado: The Devil’s Work, intertwined the story of an eighteenth-century Ghanaian man sold into slavery in Brazil and later tried for engaging with sodomy. Among the film’s most gripping scenes was the man’s whipped back, on which leash marks before the bloodshed resembled an abstract painting. Colombian-born Motta delves into colonial histories to examine how religious (mainly Catholic) oppression impacted traditions of sexual expression in indigenous societies. Through his work in film, photography and sculpture, Motta excavates the overlooked stories of intersex individuals or same-sex couples executed under stigmas of western colonialism. He connects his thesis to prevalent conservatism in our society towards the LGBTQ+ communities and freedom of sexual experimentation—and, yes, leather makes multiple appearances in his visual lexicon.

“Mapplethorpe offers both a legacy and case study in terms of his depiction of colour and idealized beauty”

His sharpest use of S&M in this exhibition parallels power dynamics in the history of race with that of art: Self-Portrait with Whip (after Robert Mapplethorpe’s Self-Portrait with Whip, 1978) (2019) is an auto-photograph (or a selfie) replicating Mapplethorpe’s famous photograph of himself with a whip emerging from his butthole, with the photograph darkened to near invisibility. In the image Mapplethorpe, who had turned himself into a tailed beast—or a devil, even—is placed before the eyes of a predominantly heterosexual audience, bringing S&M into the sterile borders of the white cube. For Motta, similar to Glenn Ligon—who made his Notes on the Margin of the Black Book (1991-93) series in response to Mapplethorpe’s infamous Black Book (1986) that had aestheticized and objectified the black male body—Mapplethorpe offers both a legacy and case study in terms of his depiction of colour and idealized beauty.

In this same manner, the Guggenheim Museum has embarked on a year-long programme, titled Implicit Tensions: Mapplethorpe Now, dedicated to Mapplethorpe’s powerful influence on contemporary queer photography, from depictions of extreme bodily experiments to studio photography and portraiture. Back in January, the museum brought together the artist’s lesser known sculptural experiments with frame, in addition to his signature photographs of slaves and masters. His colourful frames in unconventional shapes and formats spoke to his subjects’ psychological complexities. The second chapter, which opens on July 24th, pairs Mapplethorpe with contemporary queer photographers , such as Catherine Opie (the only white artist in the list), Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Zanele Muholi and, again, Ligon, influenced by his ability to convey strength and virility in posing for camera, while challenging the photographer’s depiction of race.

Mapplethorpe is further commemorated in the group exhibition Art After Stonewall, 1969-1989 at the Leslie-Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art, as part of New York’s city-wide celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. A striking work in this exhibition is an image of pioneering minimalist sculptor Robert Morris sporting an S&M-inspired attire, completed with chains and a hat. Showing off his hairy chest and muscular arms, Morris portrays a leather daddy. However, the artist was straight and posed in this fashion for his then-lover and Artforum editor Rosalind Krauss to promote his 1974 exhibition at Castelli-Sonnabend, sparking attention and criticism at the time for his promotion of hyper masculinity and appropriation of gay subculture. In response, Lynda Benglis famously placed her legendary Artforum ad, wearing nothing on her oiled body but one of her dildo sculptures, scrutinizing hyper-masculinity through her own self-fashioning.

“The intersection of S&M and art still remains a territory extensively occupied by male artists”

The intersection of S&M and art still remains a territory extensively occupied by male artists. Exceptions include artists such as Nancy Grossman, a New York-based sculptor who made captivating busts and bodies shrouded by leather masks and body suits adorned by shiny zippers, to tackle issues of power, dominance, gender, decades before a new generation of artists. Grossman, who is also a part of Leslie Lohman’s group exhibition, made around one hundred leather-covered sculptures in the 1970s, yet maintained a low-key in a male-dominated platform.

Brooklyn artist Jessica Segall, similar to Benglis, puts a tongue-in-cheek twist on work by another minimalist male figure Richard Serra, whose 1967 drawing Verblist includes a list of directions for body movements, such as bend or fold. In her in-progress body of work, Segall uses the directions coming from a straight white man and turns each direction into an act of sexual pleasure shared between a master and slave. The artist’s online porn-culled images show couples engaging with physical acts dictated by Serra’s commands. Segall’s plan for the future is to turn Serra’s dictations, which she believes perfectly resonate with power dynamics in sexual bondage, into a performance series, and eventually a video.

No doubt the rising temperatures of the summer are most experienced on the scorching platforms of New York subway, and in the exhibitions celebrating queer rebellion and commemorating the invaluable legacy of the Stonewall Uprising. And sexuality, in its every unabashed form and expression, continues to be a tool for artists to raise their fists higher up in the air for visibility and pleasure.