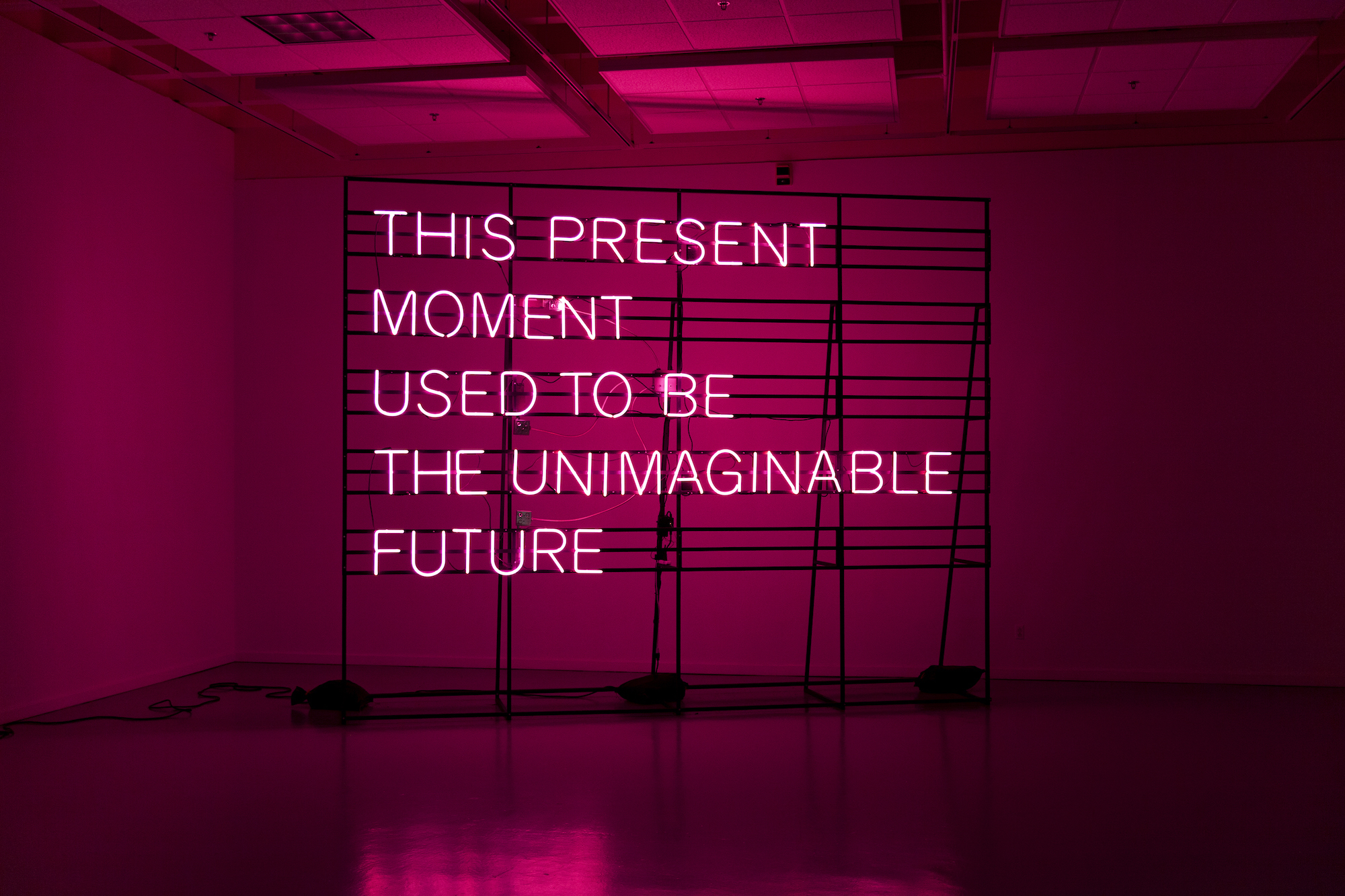

They say a picture is worth a thousand words. For Alicia Eggert, the opposite is true. The Dallas-based artist thinks in terms of ideas and messages rather than images. Her practice depends on the concept of time (the way it structures our experiences and affects our perception of reality) and her point of entry is text.

“I’m asking big existential questions that are often a bit out of my reach intellectually, so I come back to the language that I rely on every day to communicate them,” she explains. “Common language is a bottomless pit in terms of nuance, and even very simple words mean different things in different contexts.”

Text and art have been bedfellows for centuries (think medieval illuminated manuscripts), but it was in the early 20th century that the relationship blossomed. Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque collaged newspaper clippings into their Cubist still lifes to add variety and texture, while Dada and Surrealist artists used wordplay to underscore their social and political designs.

The shift came hand in hand with developments in advertising and product packaging, whose typographical elements Pop artists tapped into. With the conceptual art movement, language replaced brushes and canvas as a material and became a tool with which to disrupt the notion that an artwork should be a physical object.

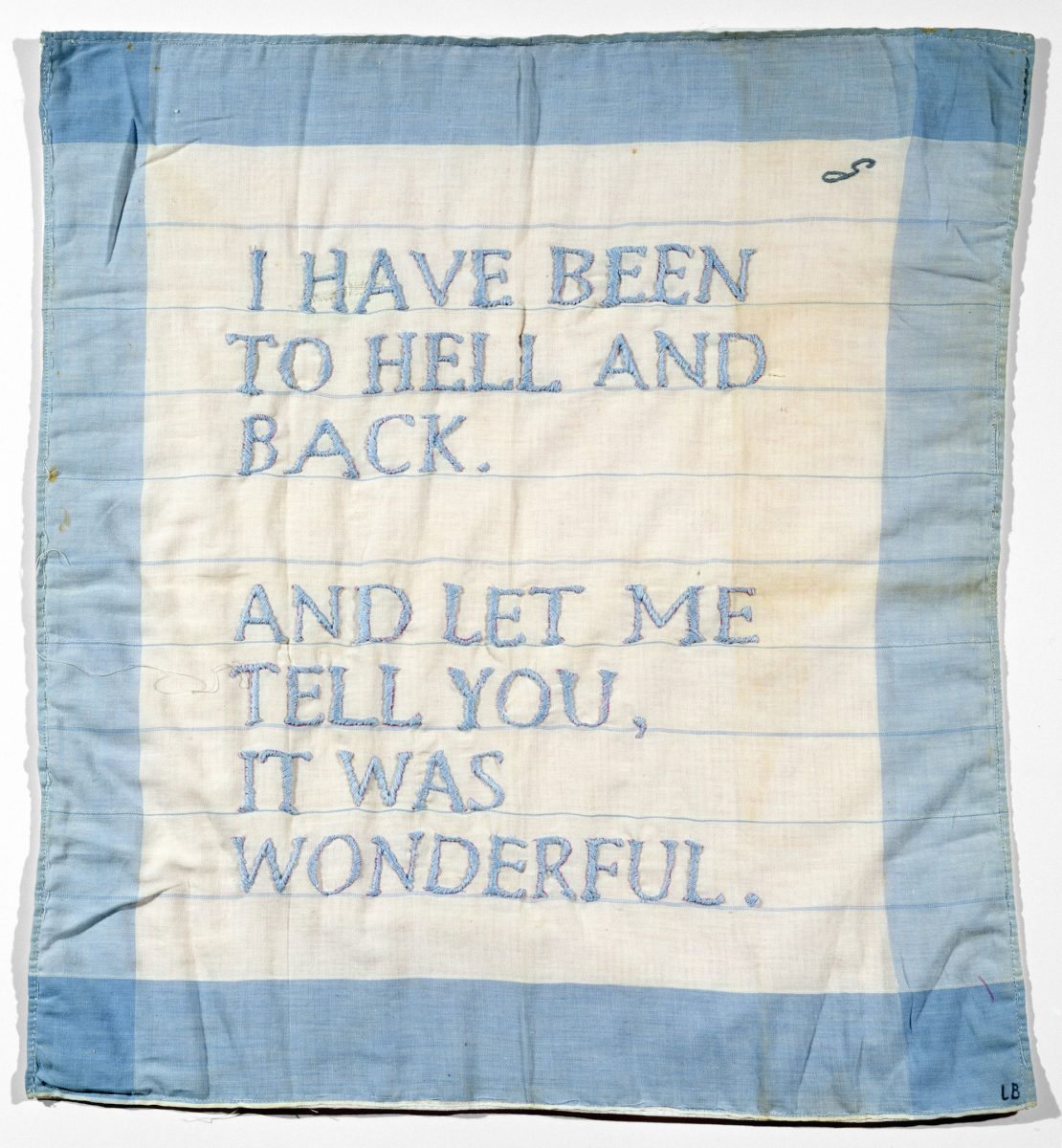

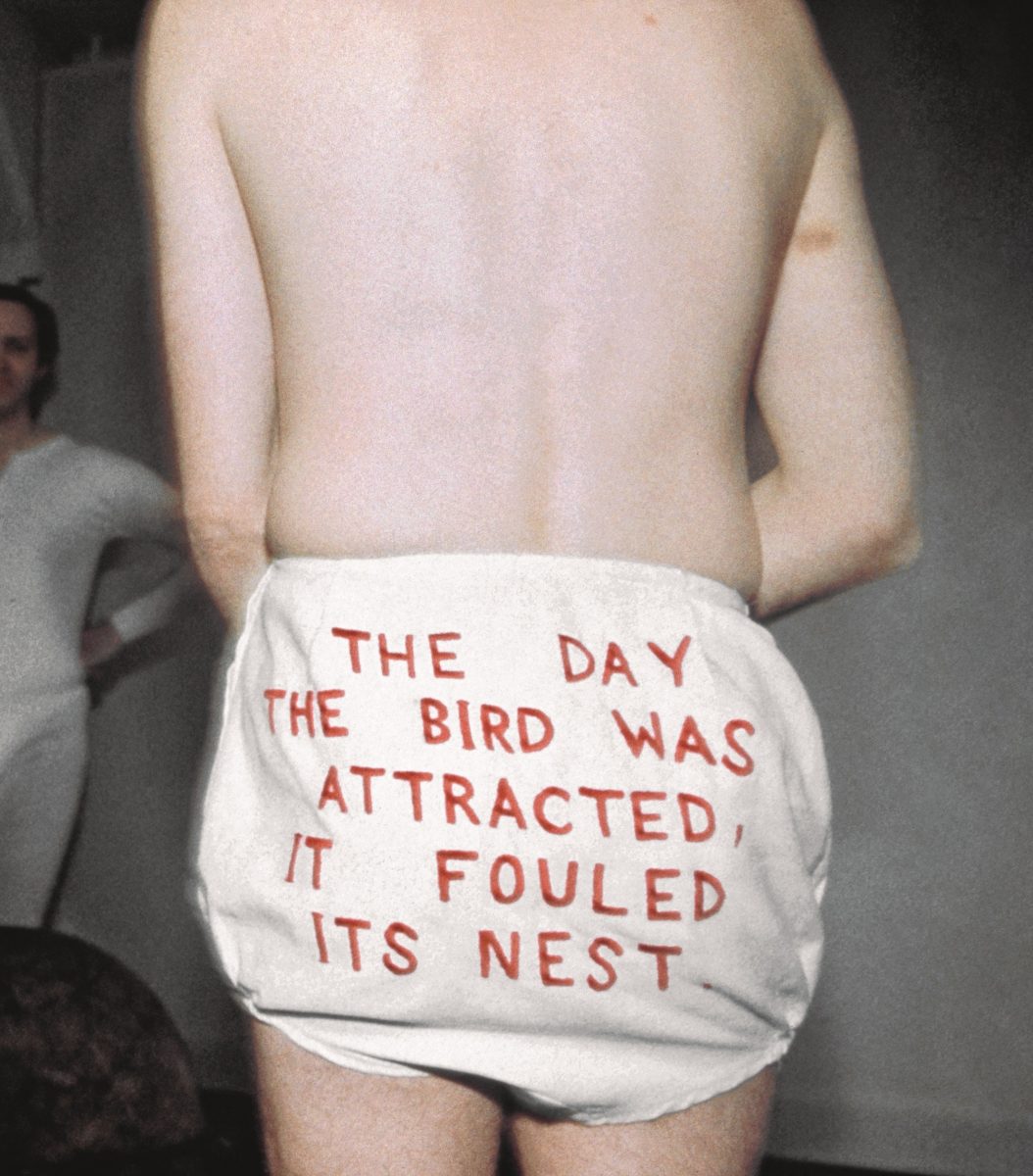

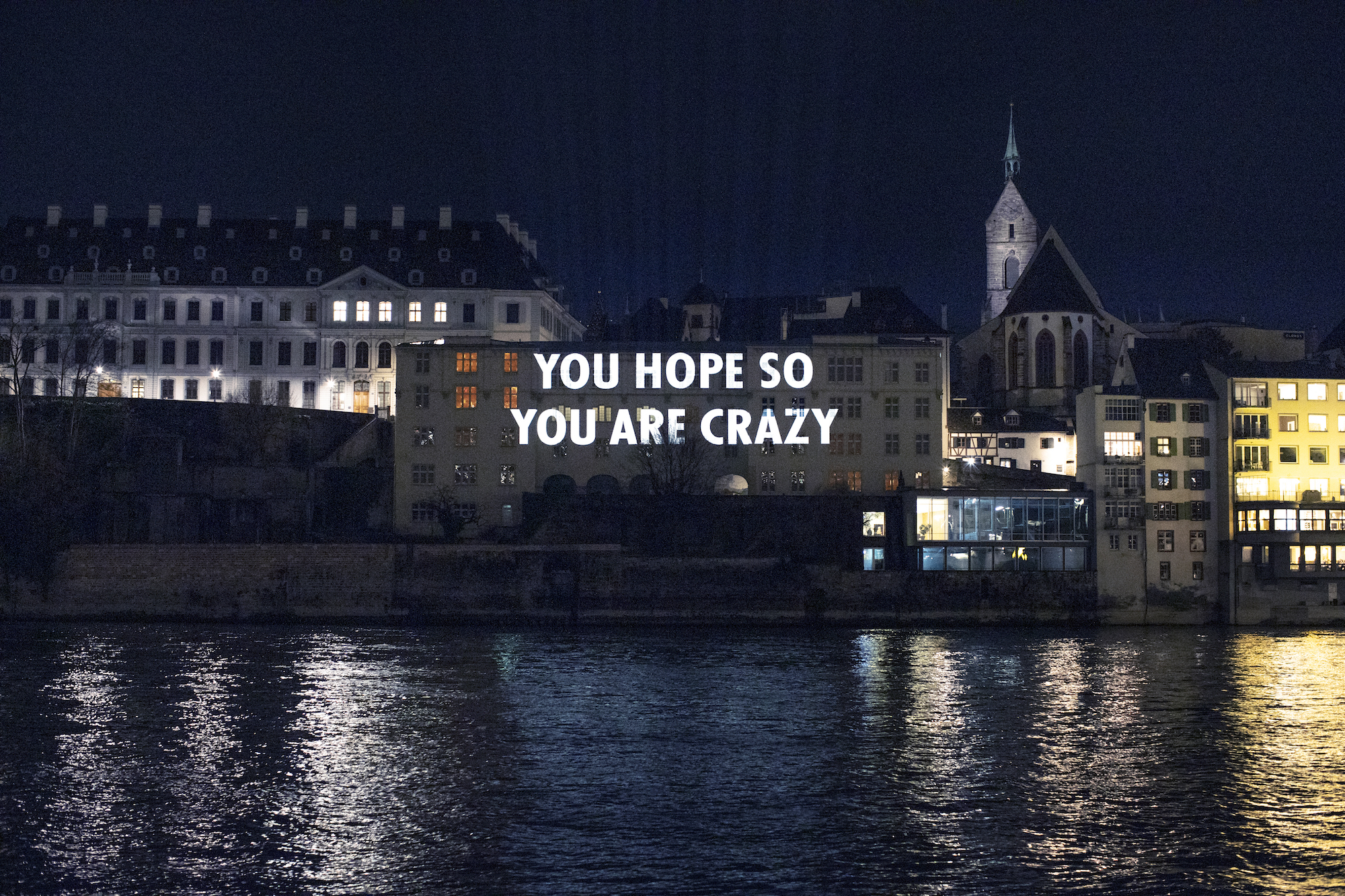

Contemporary artists continue to explore text in art in bold and innovative ways: Ed Ruscha’s word-works employ puns, alliteration and other literary devices, while Jenny Holzer is known for harnessing the power of language and projecting it into public spaces. This month an exhibition exploring language in Louise Bourgeois’ career opens at the Kunstmuseum Basel, curated by Holzer, who was a long-time friend of the late French artist.

“Text is where I go to for inspiration,” says Eggert, who reads a lot and jots down extracts in her journals. Later, when she’s brainstorming for a neon sign or a billboard, she flicks back through the pages and considers the potential of words and phrases. Sometimes she’s inspired to adapt them or to write her own version, sometimes she uses a direct quote. “But even then, by switching some words off, and by adding that element of time and animation, it can take on a whole new life,” she says. “Even when I don’t change the words, I make them my own.”

“Giving language a physical form and allowing it to change enables us to question the way words and messages relate to us personally”

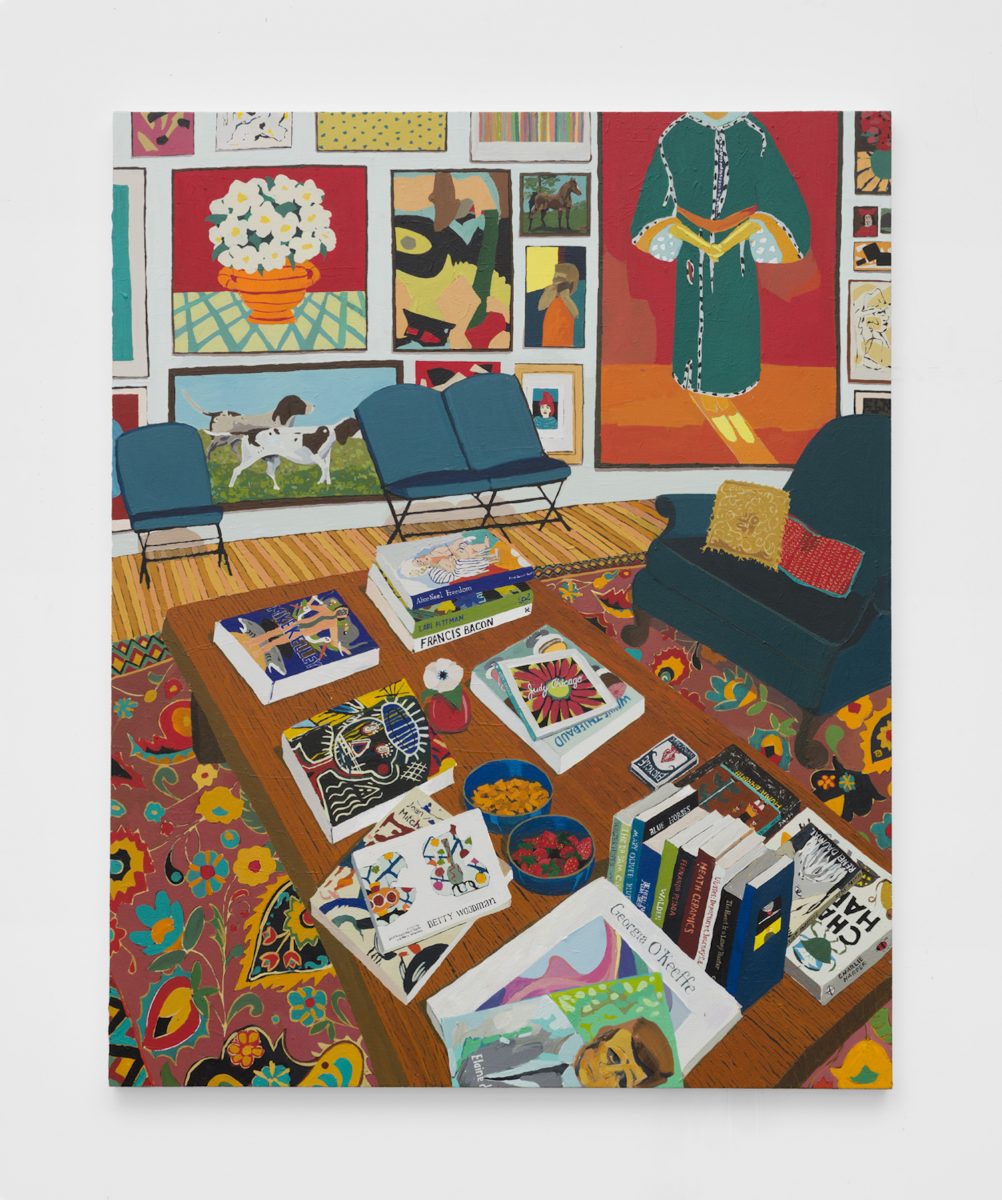

The artist Hilary Pecis also finds inspiration in text. Or rather, the text that appears on her charming canvases nods to the folk she finds inspiring. Monographs by Eva Hesse, Alice Neel and Henry Taylor appear on tabletops alongside half-full wine glasses and leafy potted plants. Occasionally, an exhibition catalogue is open and Pecis has reproduced a painting from inside.

“I work from photos, most of them taken in either my home or my friend’s home,” she says over video call from her studio in Los Angeles. “My husband and I are both artists so there are always stacks of books around. But I edit out a lot. I probably wouldn’t include a book about an artist I don’t like.”

- Left: Hilary Pecis, Adrianne's Bookshelf, 2020. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery;

- Right: Interior with Books and Paintings, 2019

Pecis edits out text itself when it’s hard to read, replacing letters with dots and lines. She’s less concerned with things being legible than she is with conveying an impression, and she’s as fascinated by the formal qualities of language as she is its content, the way words align with one another and take up space. “There are a few fundamentals that I find really interesting in paintings, like line and colour,” she says. “Text makes for a nice natural line. There’s a beautiful way that the strokes appear.”

“I love when there’s text on things I’m drawing because it can anthropomorphise objects. It lends character”

She switches to the back-facing camera on her phone and points it towards a couple of canvases by way of example. In the first, which shows a friend’s bookshelf, the titles on some spines are so small they’re illegible. In the second, depicting the window display of an Italian deli, the blurred writing on cheese wheels becomes just another pattern in the painting. Like the tin tiles lining the shop’s ceiling, it adds texture. Of course, sometimes it’s more than that: a newspaper or a calendar can act as timestamp, rooting a work in a particular time and place.

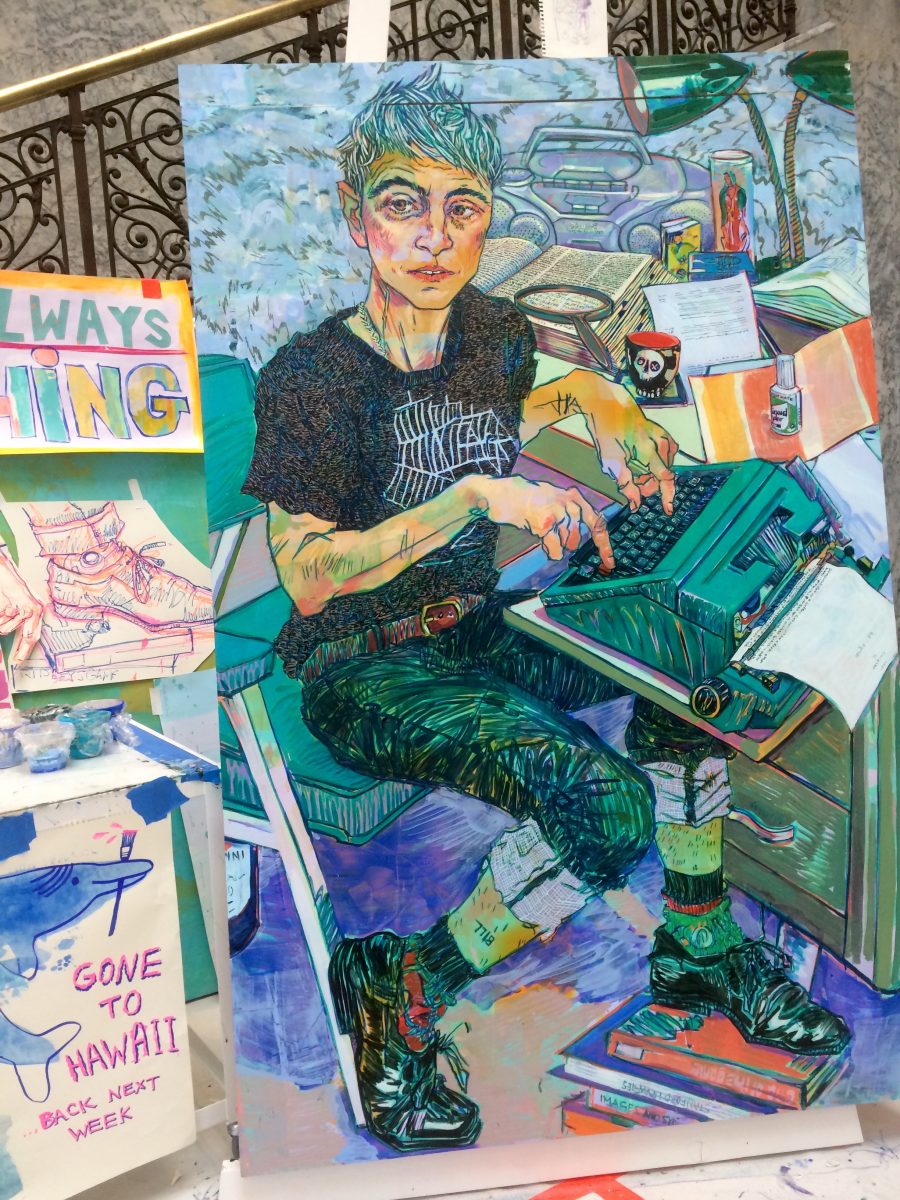

Over in New York, Hope Gangloff is painting the bumpy texture of life itself. Her repertoire includes paintings, illustrations and postcards, and as she works, she listens to the radio.

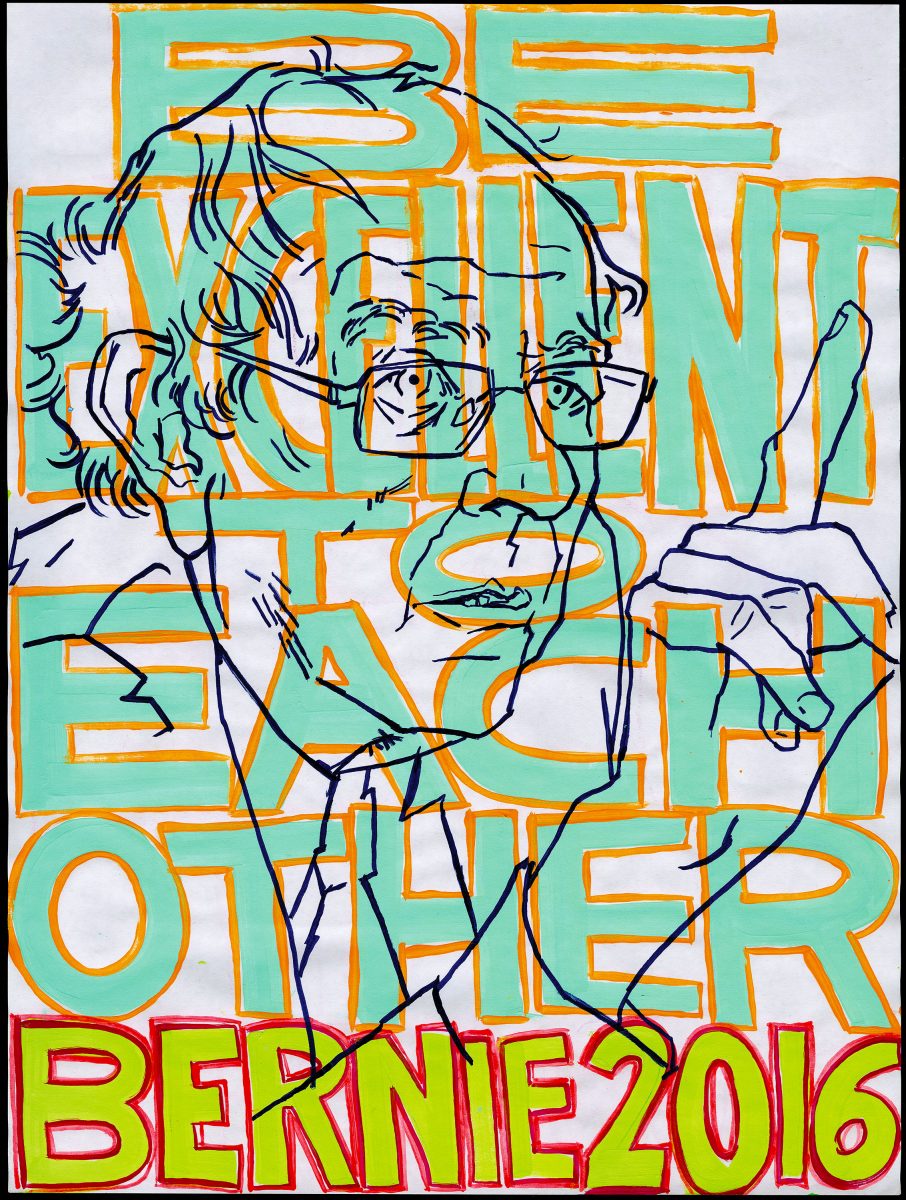

“I paint with an urgency, because there’s limited time on the planet and there are a lot of things I want to paint, and because it’s how I communicate with everyone around me,” she says. “Often the news is infuriating, and my brain goes into overdrive. I’ll start thinking about words that articulate the absurdity, and to break my brain’s fever I’ll make a text-based piece in the same colours as whatever I’m working on. It helps to relieve the crazy political stuff.”

The result are high-impact political posters. Or, as Gangloff calls them, artefacts. She uploads them to her website and encourages people to download them and take them to protests, in the same way that she did as a child when she and her family attended a rally in Washington DC against the Iraq War. “I’ve always used text to communicate, and in this case it’s hugely helpful, if you’re holding up a sign and you’re articulate,” she says. “It’s also a fun challenge because you have to make a big visual punch in a small amount of space.”

“Text is where I go to for inspiration. Even when I don’t change the words, I make them my own”

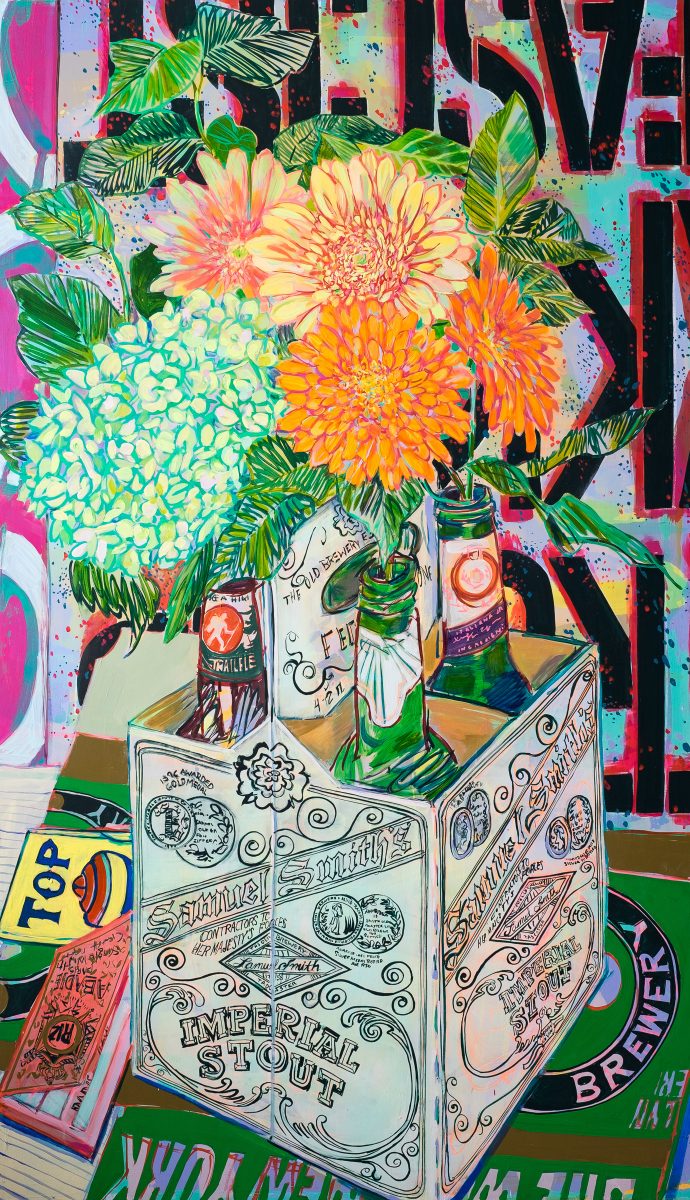

It can also be fun, full-stop. “Sometimes my text pieces are goofy,” says Gangloff. “I love when there’s text on things I’m drawing because it can anthropomorphise objects. It lends character.”

A sardine can becomes as much about the label as the wet fish inside. A box of safety matches makes you stop and wonder what it is exactly that makes them safe. What does a young woman’s choice of magazine (in one case, The World of Interiors) say about her? There are notepads and nail polishes, condiments and cosmetics. “I like there to be some kind of visual story,” Gangloff explains.

Language is more than communication. It’s a material for realising ideas. It’s direct and accessible, and when it’s turned into an object it takes on new meanings. “There’s so much to be learned from deconstructing and reconstructing something, which can be done conceptually, by looking at a word and thinking about all its definitions,” says Eggert. “Just giving language a physical form and then allowing it to change enables us to question the way words and messages relate to us personally.”

By incorporating language into their practice, these artists are inviting us to reflect on the letters, symbols and signs that fill our days. Maybe they’re spelling out more than we think?

Chloë Ashby is an author and arts journalist. Her first novel, Wet Paint, will be published by Trapeze in April