I last saw George Shaw in the small, crowded upstairs room of a Soho pub where he was singing the Morecambe and Wise signature tune, Bring Me Sunshine, while his friend accompanied him on the ukulele. We were there for the Yale University Press book launch of A Corner of a Foreign Field, a big and learned tome on Shaw’s work. The title comes from Rupert Brooke’s famous poem The Soldier. Although Brooke never actually saw active service in the First World War, his lines: “If I should die, think only this of me/ That there’s some corner of a foreign field/ That is for ever England” are the patriotic outburst of a young man contemplating the slaughter of tens of thousands in a cruel and pointless war. Since then, his words have acquired a more flag-waving, UKIP-esque resonance. It’s these complex shifts in English life that Shaw mirrors with a forensic clarity, tinged with tender romanticism, in his meticulous paintings.

Today, we’re meeting in Soho House and he’s dressed more like a prosperous young farmer from the West Country where he lives—in a smart tweed jacket and waistcoat—than a cutting-edge artist. Sitting by the real wood fire we both mention that the newly decorated room retains something of the old Soho. History, nostalgia and authenticity are important to Shaw. For more than twenty years he’s walked round the same small corner of the Tile Hill council estate in the Midlands where he grew up, taking photographs to create an encyclopaedic reference library that he uses for his paintings.

For Proust it was a madeleine dipped in lime tea. For Shaw it’s Tile Hill Estate’s run down terraced houses with their sagging net curtains, the playing fields and lock-up garages where bored youngsters hang out to kick footballs, sniff glue and look at girlie magazines that bring his childhood gushing back. But his is not a bleak dystopian vision, rather it’s a nostalgic, elegiac image of an all but vanished England, “a dream of Britain, an island I have come to know as a landscape of ghosts and haunted houses, of fair to middling weather and stony prehistory but also a backdrop for injustice, criminality, humour, suspicion and sparse grace.”

It is, he says, “a homely and unsettling vision”. This contradiction between the homely, what Freud called (heimlich) and the uncanny (unheimlich) is central to Shaw’s paintings. Although he left Tile Hill at eighteen (his mother still lives there) to study art, the estate remains the emotional core and catalyst at the centre of his work.

“As an artist you can’t just rely on style. You have to rely on intention but it’s hard. As Beckett knew there’s a lot of potential for failure but you just have to keep going”

What, I ask, did it feel like to grow up there during the Thatcher years that badly disrupted the cohesion of such communities? His dad, he tells me, worked in a storeroom of the Standard-Triumph Motor Company in Cranley Coventry, which was swallowed up by British Leyland in 1968 and then closed in 1980. After that he never worked again. But far from giving up, he took the opportunity to educate himself.

“My dad read Pinter and Beckett. We watched TV together on our little black-and-white telly, discussed the kitchen sink dramas, and endless repeats of Hammer horror films. He was a clever man, my dad, aspirational, but he had few opportunities. His motto was ‘question everything’. Mum was Irish and worked in the local pub and saw education as a way out. My sister learned Latin and somehow Dad bought us a piano. He saved money in a box file. Put away £5 a week for Christmas. He’d start doing that the previous year. We always had presents.”

And school? “Well I suppose I was a bit weird but I was never ostracized. There was a lot of violence around then with skinheads and racism around Coventry. But I was mostly up in my bedroom reading. It was a bit of a disappointment, then, when I eventually got to the Royal College expecting this rich cultural life to find that no one much read. My dissertation was on the body in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist As a Young Man. Before that—in 86 to 89—I was doing my BA in Sheffield. I’d been painting in my room since I was ten, life drawing since I was eleven. After my degree I got a job as a medical illustrator at Charing Cross and Westminster Medical School, because I could use a video camera. Then I moved back to Sheffield, worked as a secondary school teacher, teaching children with learning difficulties and had a small studio. Loads of the people there were applying for the Royal College. So I thought, I’ll have a go. I can do that. Though the work I was doing then was closer to Rauschenberg than anything I do now.”

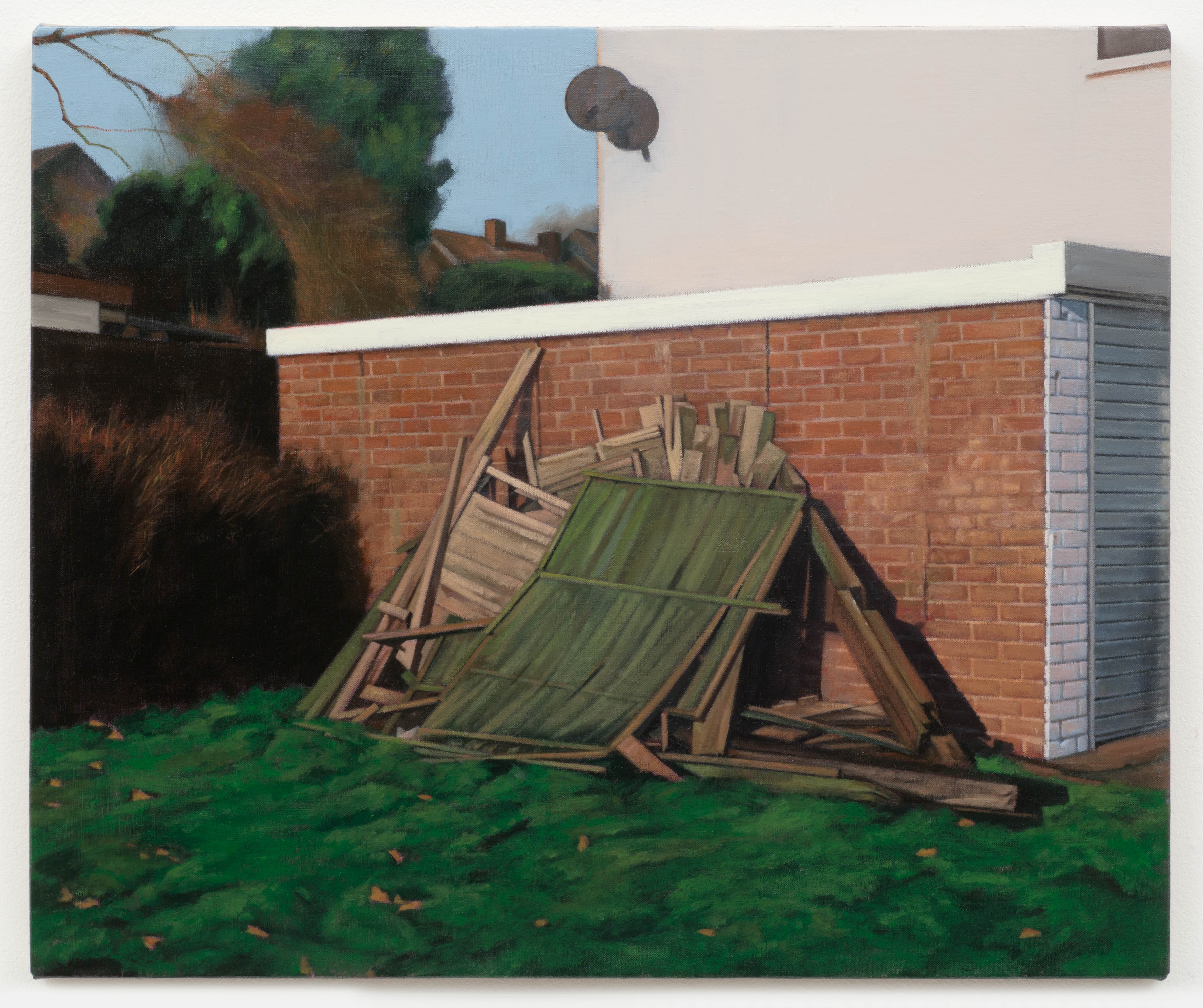

The Man Who Would Be King, 2017

From an early age Shaw had a natural talent for drawing (his uncle was a gifted self-taught artist). At the time the Royal College of Art was a bastion of painting under Paul Huxley, but he didn’t want to offer Shaw a place, saying he’d be depriving kids of a good special needs teacher. Shaw’s response was to demand “a fucking place”. He got in. This allowed him, even as the 1997 Sensation opened at the Royal Academy showcasing the slightly older YBAs, to follow his own trajectory. It was at the Royal College that he embraced Tile Hill as his core subject. At first he’d treat the graffiti he found on a garage door, say, in a gestural way. Then someone suggested he just paint the door instead of pretending to be an expressionist.

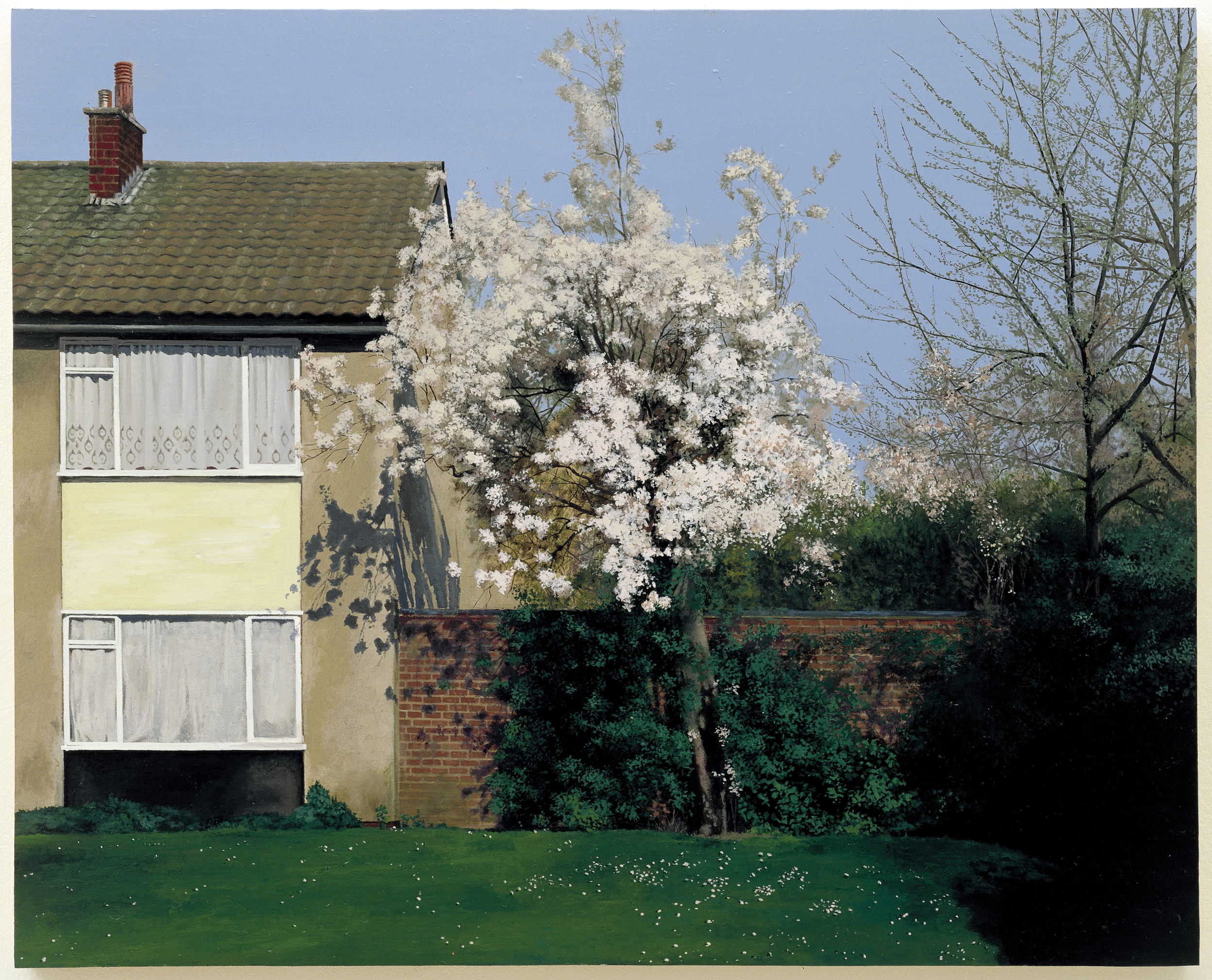

The result has been an extraordinary body of work famously created with Hombrol paints—enamel paints traditionally used for painting model airplanes—which has become a love song to the suburbs. An acute observer of the shades of English life, he’s made poetry from the council estate and odes from playgrounds and wasteland. This is a world where the slow erasure of the pastural dream has gone almost unnoticed, as woods become liminal spaces between suburb and country, between then and now. His sylvan scenes from the Passion series resonate with the romanticism of Caspar David Friederich. While others from the same series, such as The Blossomiest Blossom, reflect the spirituality of his lapsed Catholicism. His rows of modest houses also speak of loss. Of a post-war utopianism, expressed through architecture, that believed in social change and a fairer society.

“There’s a way that this place is always home. I had a happy childhood there. I remember watching the play A Voyage Round My Father with my dad in our living room”

There is a strong desire to create narratives from Shaw’s work. Yet the most recent story, suggested by the Cross of Saint George flag sagging in one of the windows of the estate, is a tougher and more despairing one than the warmth expressed in his earlier more wistful paintings. This is the tale of the hubris and xenophobia that is Brexit. Entitled The Man Who Would Be King, the painting resonates with a sense of collapse and spiritual dilapidation.

“When I went back to the estate,” he says, “I wondered what I was doing there. I thought I had nothing more to say. I resisted doing the flag paintings for a year. I worried I might seem condescending or even right-wing. Might be criticized for living in a nice house on Dartmoor and painting a shithole. But there’s a way that this place is always home. I had a happy childhood there. I remember watching the play A Voyage Round My Father with my dad in our living room. It’s a strong memory. I suppose we’re all continually looking for our home, even though we know ‘the past is another country’. Still, we try and find the unfamiliar though the familiar. As an artist you can’t just rely on style. You have to rely on intention but it’s hard. As Beckett knew there’s a lot of potential for failure but you just have to keep going. I think it was Novalis who said, ‘Philosophy is really home sickness: the urge to be at home everywhere.’” The same might be said of George Shaw’s paintings.