All images courtesy Rod Barton

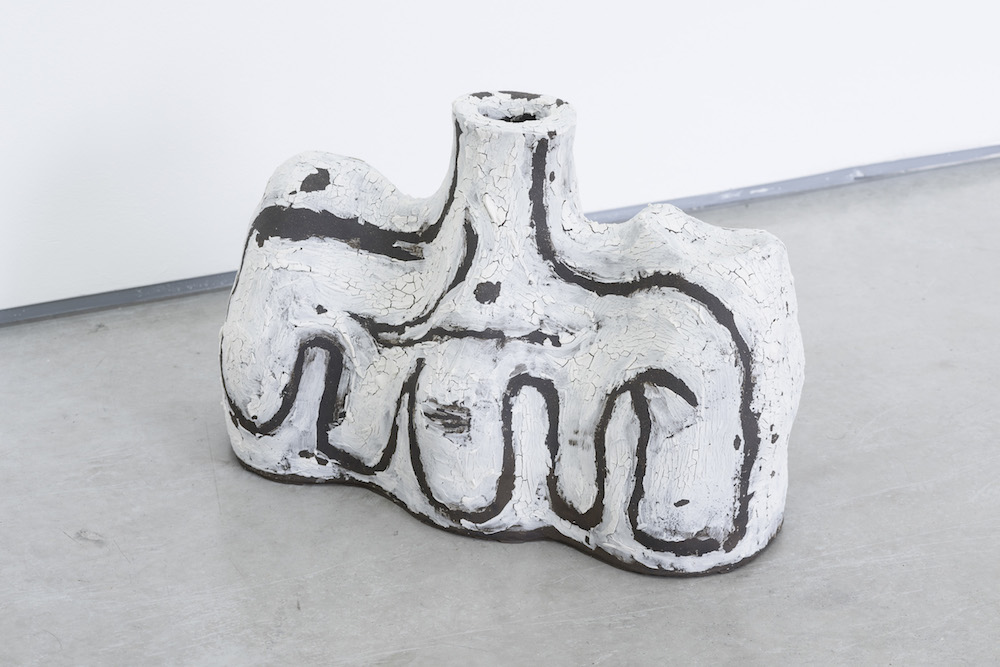

Three young men have taken over Rod Barton’s Peckham gallery with propositions about the state of clay and its relationship to painting. They are called Laurence Owen, James Collins and Tom Volkaert. They share a few things in common, aside from their deep attachment to their studio practices, and their fondness for playing with clay (the recent resurgence of which Barton attributes to its cheapness and availability). They have all dabbled in other physical practices—Collins was a semi-professional footballer, Antwerp-based Volkaert still moonlights as an art handler. Seeing the nuts and bolts, the behind-the-scenes of transporting and installing art, Volkaert says, is an inspiration in his sculpting. He has no training in the medium (he studied printmaking but has since abandoned it) and as a consequence his process is very experimental, freestyling, giving his works their gloppy, unstable look. The two anthropomorphic sculptures in this show, which beckon you in from the street through the window, their protruding phalluses/noses pointed to each other in a self-defeating battle, are an example of this inside-out approach, their structural screws and bolts made visible to the world, with plenty of space to walk around them.

What do you get if you mix clay with paint? On the other side of the gallery, muscularity meets warts-and-all fragility again, in the roughly-fashioned steering wheels that stick out from Owen’s painting, depicting a deliberately obfuscated copulating couple. Taking memories of fleeting moments and interactions as a source, Owen is a master of fragmentation, the blocky lines and graphic aesthetic sense of his sculpted-paintings also reminiscent of neo-surrealism. A glazed ceramic sculpture titled Hand by the artist has a flakiness to it, and looks more, disorientingly, like a dinosaur foot.

Owens describes his co-exhibitor Collins’s work as “painting with a capital P”. He’s bang-on. Collins’s thick, gestural works are the result of a laborious process of layering and digging emphatically into a plastic, epoxy resin impasto he makes out of various materials (no-one is quite sure what goes in it) dark, gloppy swathes, almost, in fact like the churned up turf of a football pitch. There is something almost self-flagellating about this process, making a material so dense that it makes it almost impossible to work with. Various figures and semiotics start to emerge from the darkness if you stare at them long enough.

But what are these three artists, with their aligned interests and techniques, trying to tell us? Their questioning begins in form, in the age-old battle of painting versus sculpture, but it veers briskly into other areas. Everything looks, materially, as if it is about to collapse or crumble, and human gestures are deconstructed and deformed.

Pushing forward with this dialogue between structure and form, using their processes of adding and subtracting to confront what Owens describes as “the baggage of art history”, slipping between sanity and obscurity, steering wheels that drive you nowhere, paintings so dense they cancel themselves out, these three young artists together give you a world of dissolving stability, trippy and cartoonish. It is art-making that is about “letting go and listening”, as Owen puts it. I think we can agree, we need more of that.

Lost & Found: James Collins, Laurence Owen, Tom Volkaert

Until 2 December at Rod Barton, London

VISIT WEBSITE