What do we keep and what do we leave behind? In the modern-day, it has become increasingly difficult to define. Layers of our digital history lie dormant but ready to be unearthed, with forgotten photos lingering in the Cloud, while landfill sites are at breaking point as we sit on the cusp of one of the biggest environmental crises in history. We leave our mark on the earth, circulating products, ideas and services in an ever-accelerating global economy.

Palimpsest, a new exhibition at Lismore Castle in Ireland, delves into the many layers that make up our contemporary moment, looking at traces of people past and present. Originally a manuscript or document that has been erased or scraped clean to be reused, the word palimpsest has since come to mean “something reused or altered but still bearing visible traces of its earlier form”. Curated by Charlie Porter, the former menswear critic for the Financial Times, it explores connections across time, looking at what endures and what disappears.

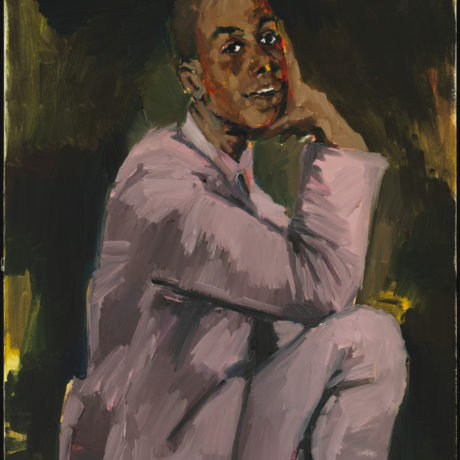

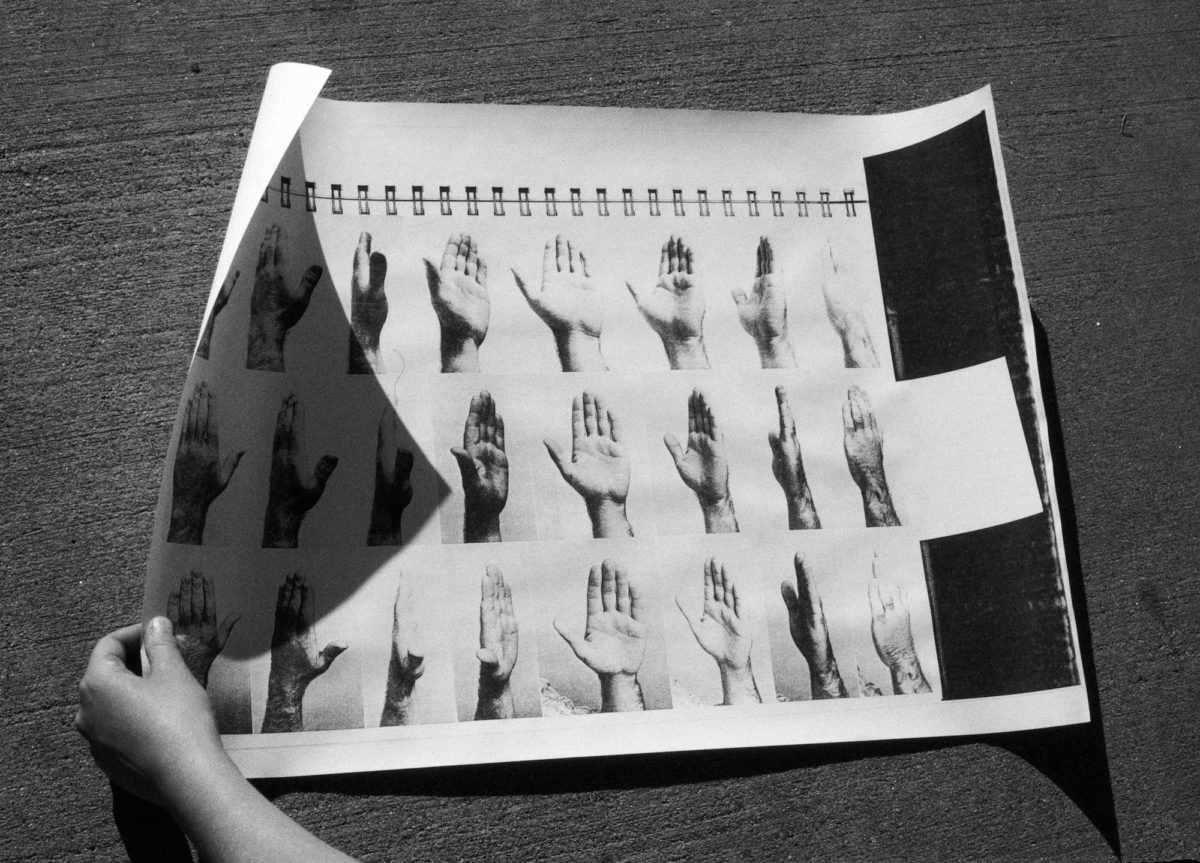

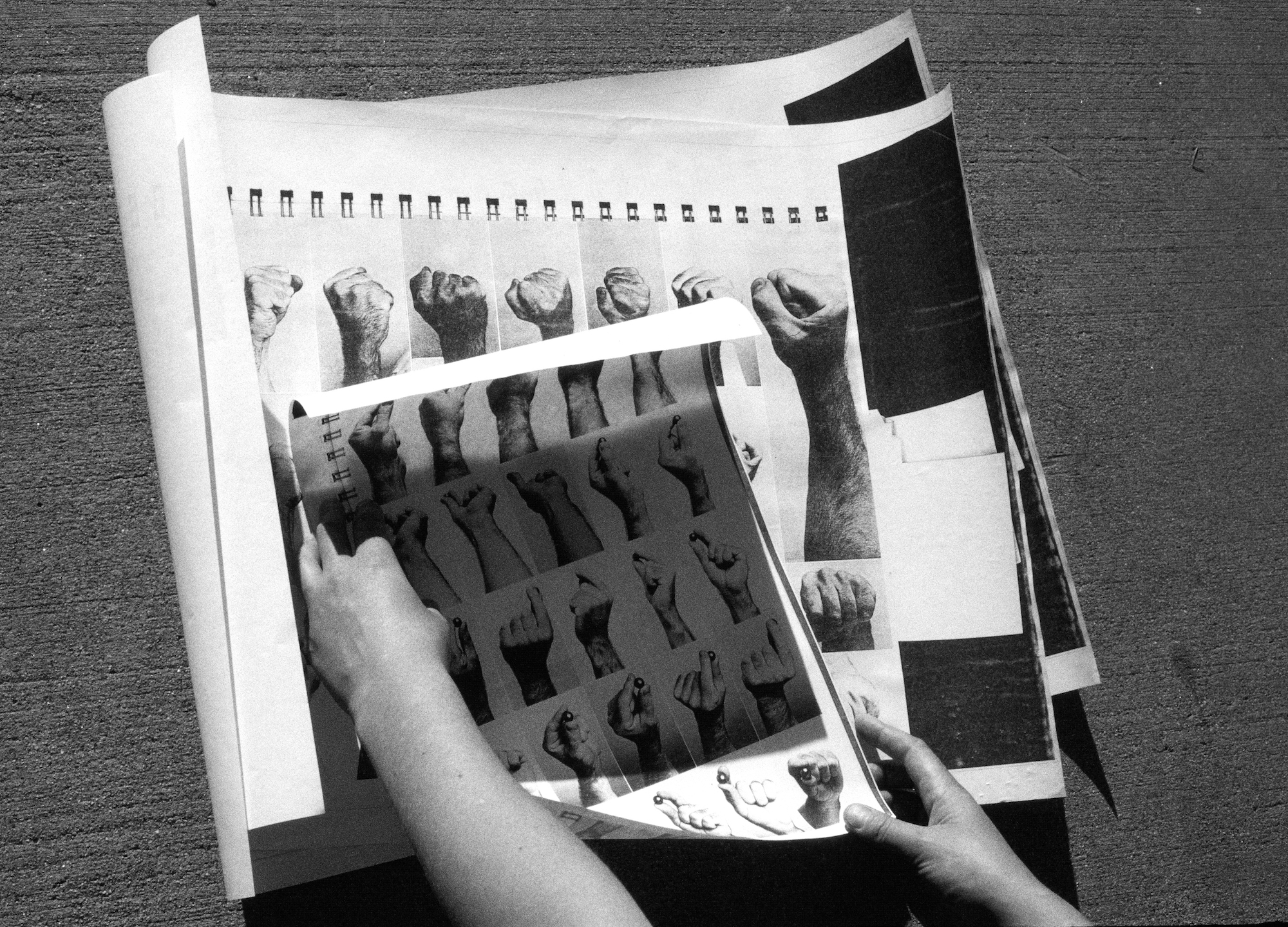

The exhibition features Nicole Eisenman, Zoe Leonard, Hilary Lloyd, Charlotte Prodger, Martine Syms, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Andrea Zittel. “Each of the artists is looking at time in different ways, as well as location and our existence,” Porter tells me over the phone. “Really big stuff but in non-showy ways—very personal ways—there’s no arrogance. They’re really deep in and trying to connect with something.”

“I’m sure that in the past, when people wrote that document or built that space, they were sure that this was its sole purpose. But then it was scratched out and reused“

“The starting point for me was Charlotte Prodger—the starting point for me is always her—I’m a super fan,” he laughs. “I’d seen her film Bridget for the first time a few months earlier in New York, and knew Charlotte would get so much from the nature and space of Lismore Castle. She has a different way of viewing time, exploring how ancient and modern are both the same, and queering nature.”

I want to know, how does the ancient notion of the palimpsest translate to how we process history today? “The way that I’ve been thinking about the palimpsest is not just in terms of what this space was before, but what it will be after. Could it be that what we know as human rights, which we assume are solid and unshakeable now, they could go? There is a sense of where are we with our certainty about things,” he says. “I’m sure that in the past, when people wrote that document or built that space, they were sure that this was its sole purpose. But then it was scratched out and reused, or a space is repurposed.”

In the digital age, this repurposing and reinvention inevitably takes place on a far wider and faster scale than ever before, I suggest to Porter. The idea of a single author, even, is vanishing. “The palimpsest is the original meme,” he agrees. “It can travel and transform in so many ways. A lot of that is in Zoe Leonard’s work for me more broadly, and we’re showing an image of hers that looks at how nature reclaims urban spaces: a tree trunk coming through the pavement. This really resonated with me.”

Palimpsest will be Porter’s first exhibition as a curator, having made the move from the world of fashion to art. “I’ve always found the relationship between journalists and artists really difficult,” he muses. “I was really happy to discover fashion criticism, which I found more rewarding. I’ve never approached art as a critic, so there hasn’t been a huge shift for me in approaching this show—it’s been more about opening up my relationship to art. It’s been about getting to know artists in a longer term way; talking with artists, sharing ideas and seeing where we can go with it. It’s like an opening up.”

Finally, I am curious to hear how this unusual route to the art world impacted on Porter’s curatorial direction for the show. “The process behind art is such an important part of it. It’s a palimpsest,” he concludes. “Making art is a lived experience; it’s a living experience.”

Palimpsest curated by Charlie Porter

At Lismore Castle from 31 October to 13 October 2019

VISIT WEBSITE