Contributor Phin Jennings gives his highlights of his trip to the city of Palma where he explored the endless galleries the city had to offer with the help of the Italian curator Francesco Giaveri.

Sunday 14th January, 2024: on the evening of the second and final day of a short trip to Palma—my first—I suddenly begin to feel light headed. Why? It might be a rush of inspiration from having taken in so much of the city’s art landscape in so short a period. It might be a sudden onset of adverse effects from the many cervezas sin alcohol that I have put away over the weekend. It might be the image in front of me, Don’t Worry Darling (2023) by David Yarrow, a photograph of a supermodel and a poodle driving a vintage car down a palm tree-lined boulevard, away from a crime scene. I’m staring into the window of Galeria K, a Mallorcan gallery that represents the hedge-funder-turned-gaudy-photographer. Either way, it’s time to go home.

Palma is a city that, more than others, needs a gallery association. There are tens, if not hundreds of galleries in the city (although, not all of them are worth seeing). As you might expect of a place surrounded by the second homes of many leathery-skinned Brits, it contains more than its fair share of art galleries that function more like shops than incubators of art. Places where, instead of a considered programme of exhibitions, you will find a crowd of shiny and colourful objects available to take home.

Enter Francesco Giaveri, the Italian curator who runs Art Palma Contemporani, an association of galleries in and around the city with grander ambitions than to simply be Neo-pop vendors for second-homers. He has invited me back to join him for a tour of such galleries. Pounding the pavements of Palma together—which is what I spend the duration of my second visit doing—it is impossible to get more than a few metres without being stopped by a smiling acquaintance, more often than not an artist or dealer. For someone with so many friends, Giaveri must be ruthless. I can see that building APC has been an exercise in exclusion, and I’m sure that he has delivered more than a few rejections.

Notably absent from our programme is a visit to the Julian Opie exhibition taking place at the Llotja de Palma. I’m glad—I get more than enough opportunities to see Opie’s work at home. London is replete with well-funded institutions and outposts of global commercial galleries where recent art history is played out repeatedly, and I have been fully desensitised to the work of the YBAs.

Living in a global contemporary art capital, it’s easy to believe that other cities’ art scenes are weak imitations of yours, but Palma has much more going for it than its ability to emulate London—it is at its best when it plays itself. It’s a unique city in more ways than one, with a lot of things that London doesn’t have, and the galleries and projects that harness this uniqueness are invariably the most interesting ones.

I’ll start with an obvious point: cheaper rents. Axel Balazsi and Antoni Fermay both spent time living in London before opening galleries in Palma. Now directors of Tube Gallery (opened in 2023) and Galeria Fermay (opened in 2022), both on the northern edge of the city, have leapfrogged the years of living-room-sized spaces that London dealers tend to begin with. Both galleries are vast and well appointed, allowing Balazsi and Fermay to mount large-scale shows on emerging-artist budgets. For example, Tube Gallery’s current exhibition Mystic Cool is British painter Mattia Guarnera-MacCarthy’s first solo show. Tens of the artist’s airbrushed paintings form a sprawling comic-strip across the gallery’s two floors, accompanied by a newly commissioned film about his life and work. Surrounded by closely-cropped quotidian moments and surreal, filmic snapshots, I feel that I am entering Guarnera-MacCarthy’s world, and understand that a London debut wouldn’t have been so expansive.

For a better-funded outfit, the prospects in Mallorca become dizzying. A short drive out of Palma, CCA Andratx is a privately owned institution that founders Patricia and Jacob Asbaek built in 2001. Set around a Roman style courtyard, it contains multiple live-in art studios alongside over 75,000 square feet of exhibition space, 2,000 more than White Cube in Bermondsey. Muy grande.

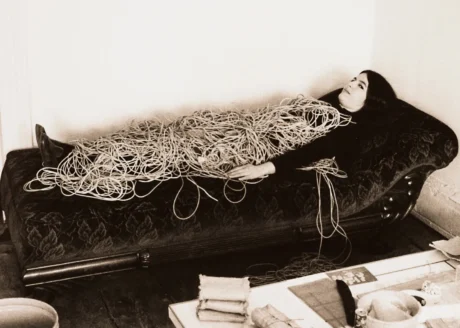

What they might lack in scale, many of Palma’s galleries make up for in architectural interest. After founding her eponymous gallery in São Paulo in 1999, Maria Baró recently moved the operation to a 17th century building in the city’s gothic centre. Currently, Portuguese artist Joana Vasconcelos’ bulbous forms hang from the walls and ceilings, drooping and bejewelled, surrounded by columns and Mallorcan stone arches. Nearby, German gallery Kewenig has an outpost in an 11th Century church, complete with the original altar stone which presides over each exhibition. It doesn’t set a passive stage for the work on show but actively interacts with it. Currently, the crudely sculpted and painted figures of Paloma Varga Weisz and Heinz Ackermans form a kind of ghostly congregation; sitting, laying, kneeling and creeping around the room, readying themselves for the coming sermon.

Impressive spaces aside, there is something else that makes Palma’s art scene special—something that quickly becomes clear on a walk around town with Giaveri meeting various local characters. In my experience, members of the art crowd in most major cities like to seem jaded, overstretched—too many important things to do to be enjoying themselves. Here, that isn’t the case. The gallerists, artists, curators and collectors seem to genuinely love art, and they contribute generously to the local scene.

Not only does everyone in this city know each other, but they are interested—often involved—in each other’s projects. Take artist Julià Panadès, who runs TACA, a small project space that hosts what he calls a microresidència, allowing artists and curators to take over the tucked-away space for a few weeks at a time. Around the corner, he has a solo exhibition at the more commercial Galería Fran Reus, showing ocean-worn assemblages made out of discarded objects found on the beach. The centre is a holy-looking structure made of sand, where a ceramic Snoopy bathes in front of a perpetually setting sun, surrounded by disposable lighters. I have no idea how the gallery will sell this shrine to the island’s gifts, but I am glad to have seen it.

My second weekend on the island ends more positively than my first. I am invited to visit COSTER, an artist’s residency and sculpture park run by Amador, the mononymous Mallorcan sculptor. Living and working on a rocky hill a few miles outside of Palma, invited artists are encouraged to work in concert with the landscape, producing artworks that exist in harmony with their surroundings. Clearly, it is a labour of love for Amador, who himself lives nearby and takes a hands-on approach to supporting residents’ productions. When I ask him in my broken Spanish what made him start the residency he shrugs, as if the answer is obvious: ¿por que no?

Words by Phin Jennings

Note: the title of this article was inspired by Croydon Plays Itself, Harold Offeh’s 2019 exhibition at Turf Projects about the uniqueness of the often-overlooked South London borough’s identity and history.