During the age of transatlantic slavery, trade winds allowed sailors to cross the oceans with greater efficiency at different times of the year. Travel from Europe or Africa to the Americas benefited from these seasonal winds, creating systems of westwards movement either side of the equator, and forever entwining the practice of slavery with Earth’s meteorology.

Migration—both forced and unforced—has been a major influence for Paul Anthony Smith, whose latest exhibition of photography-based works borrows its title from these natural cycles. Smith’s practice seeks to reconcile the differences between populations, cultures, landscapes and languages that have been displaced or partitioned by colonialism. He casts his lens from east to west Jamaica; Aruba to Barbados; and on the Caribbean diasporas of London and New York. He retraces historic patterns of movement, but empowers his subjects to exist beyond these colonial labels.

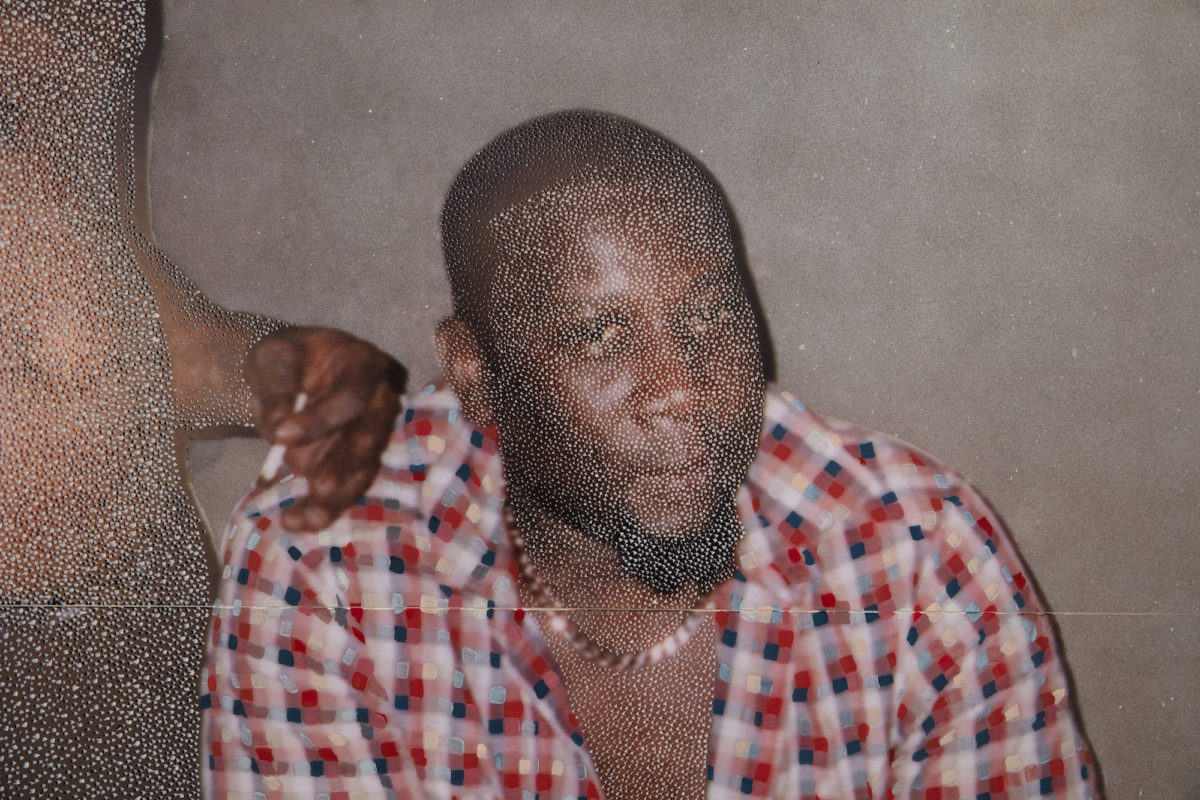

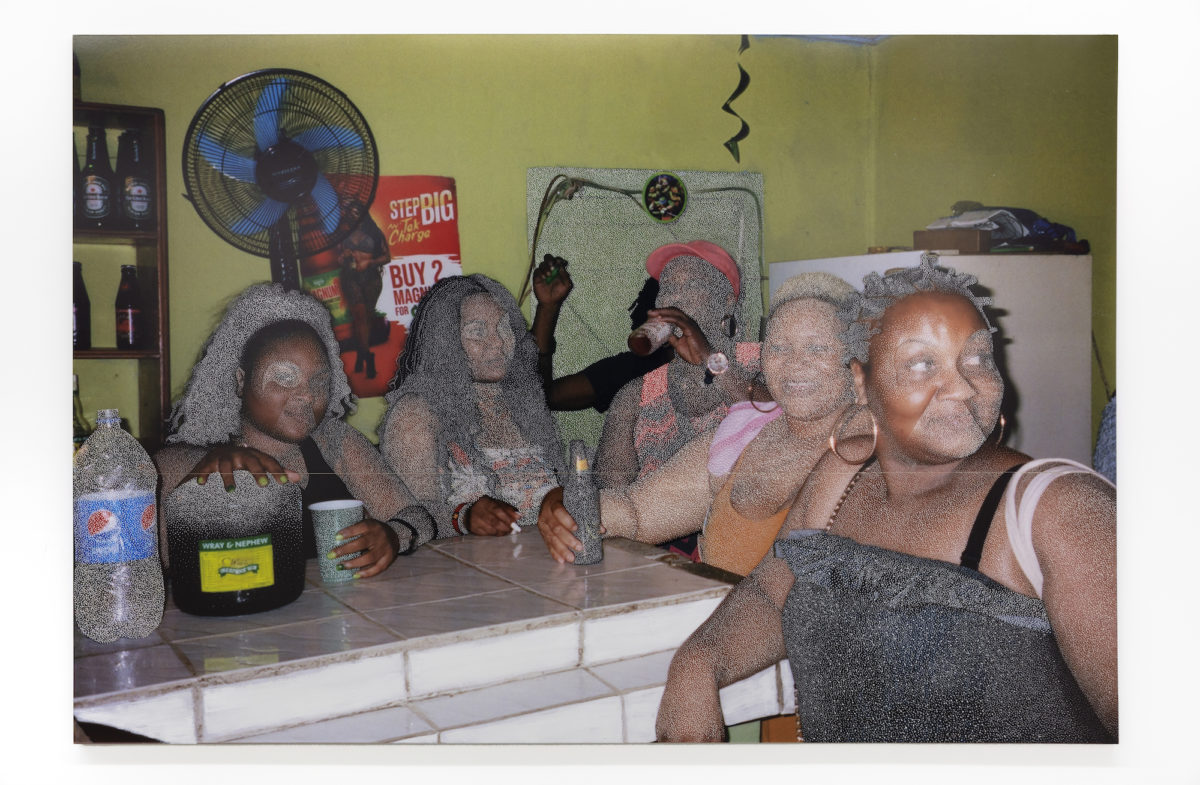

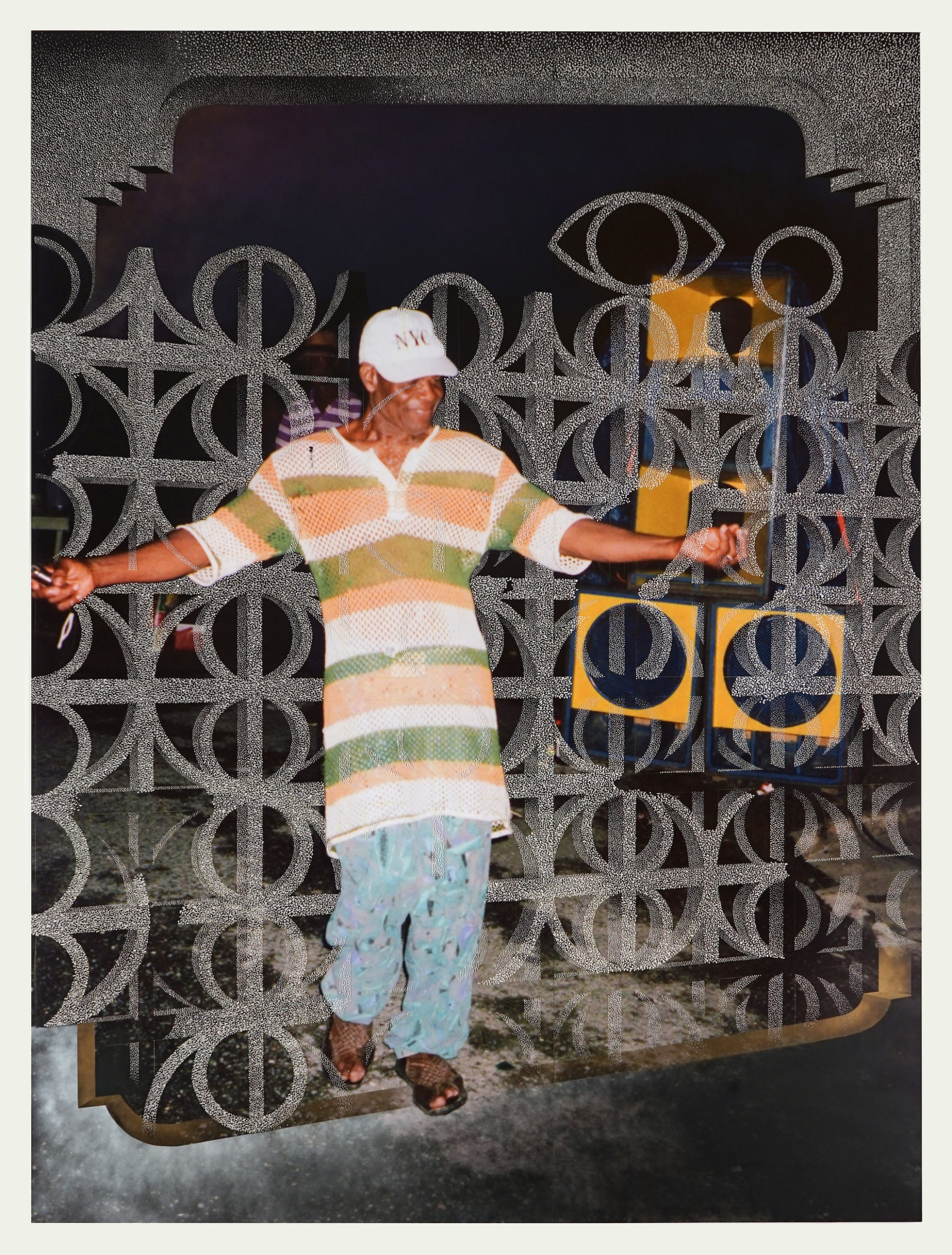

Paul Anthony Smith, Dog an Duppy Drink Rum, 2020-1. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

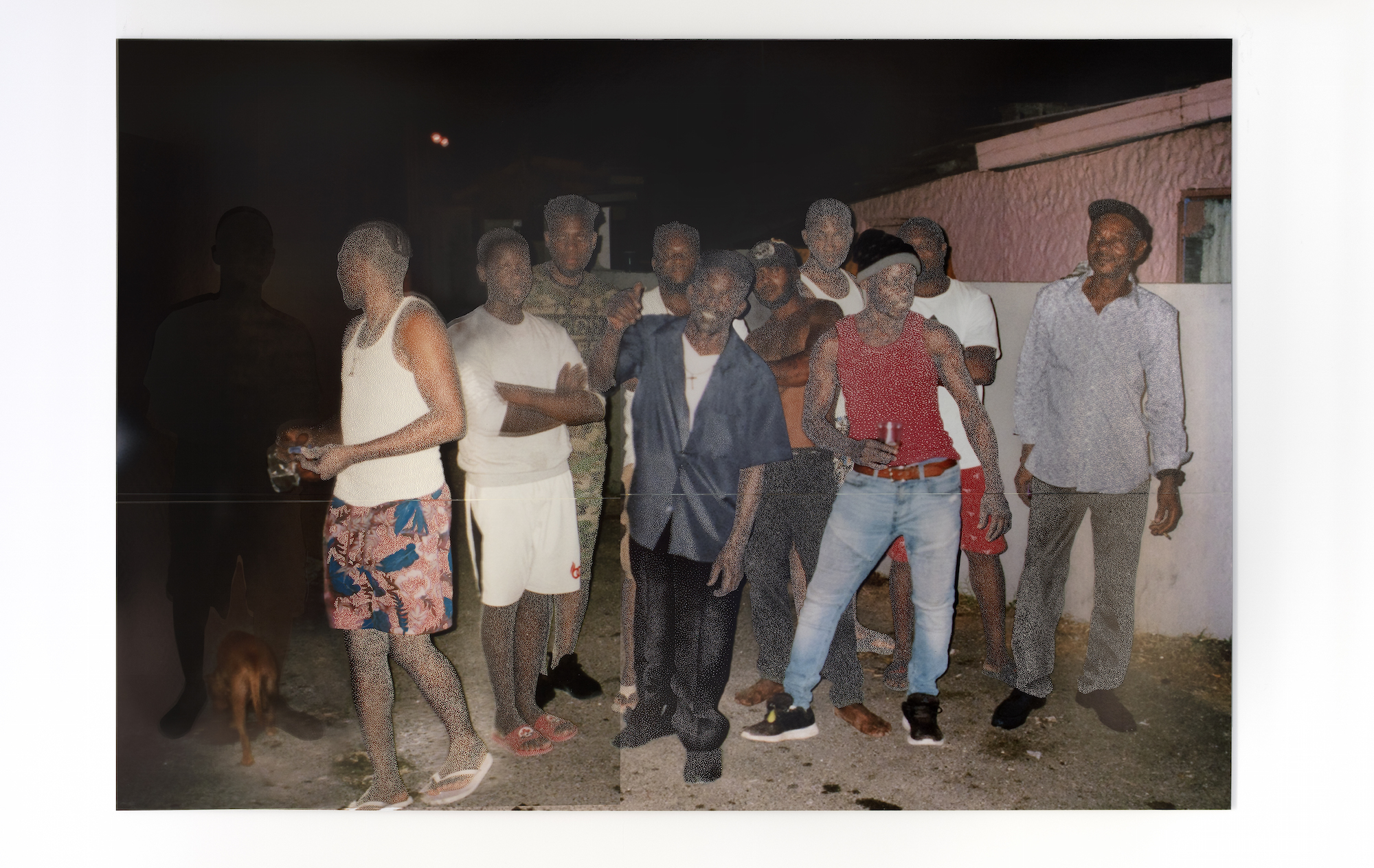

“I think about these people that I show occupying spaces and being themselves and being explorers and travellers,” Jamaica-born Smith tells me from New York City. He shoots subjects in a range of casual settings—

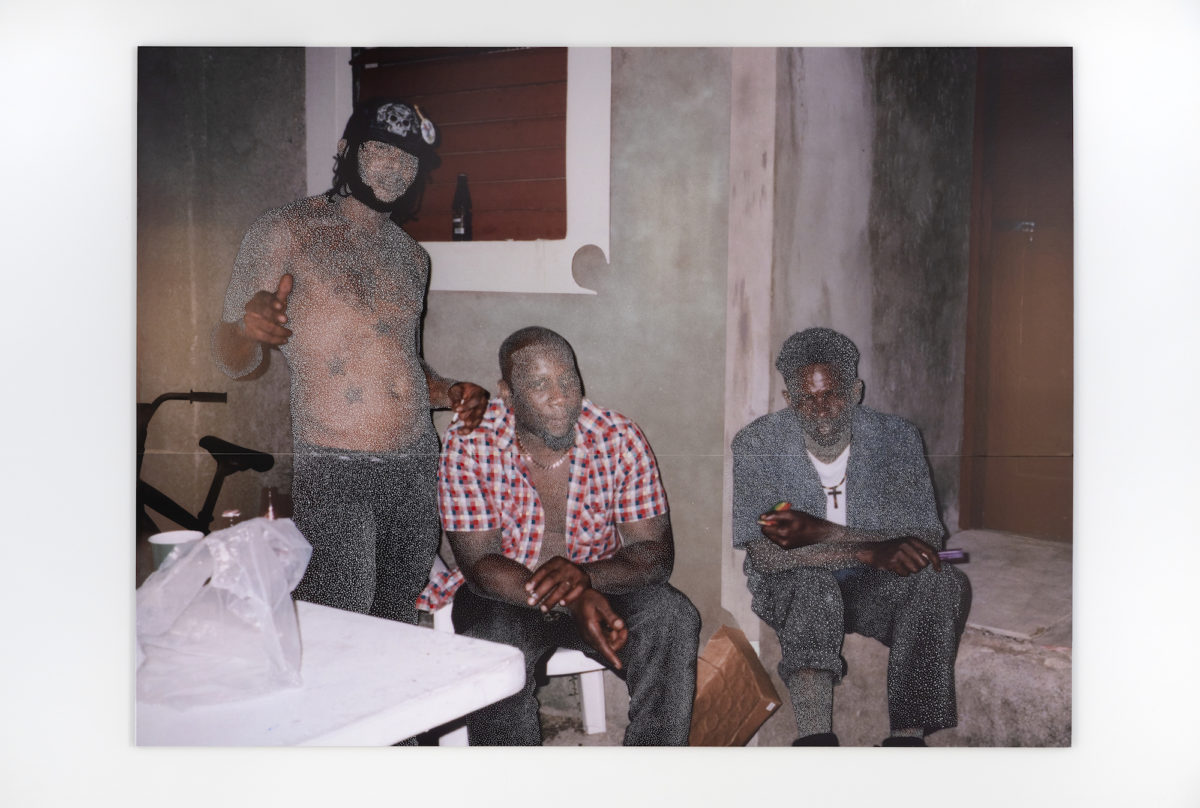

their familiar, homely environments representing a milestone in each of their journeys, rather than a fixed stasis. The exhibition emerged from his own journeys in 2019. While visiting London for Notting Hill Carnival, Smith was informed of the death of a relative in Jamaica and returned to partake in the traditional Dead Yard commemorations—an extended wake-style celebration involving dance, games and large feasts. “

While that was happening I was thinking a lot about fatherhood and manhood,” Smith says. “What does it mean to be a man from the Caribbean and to be a provider?”

“I think about these people that I show occupying spaces and being themselves and being explorers and travellers”

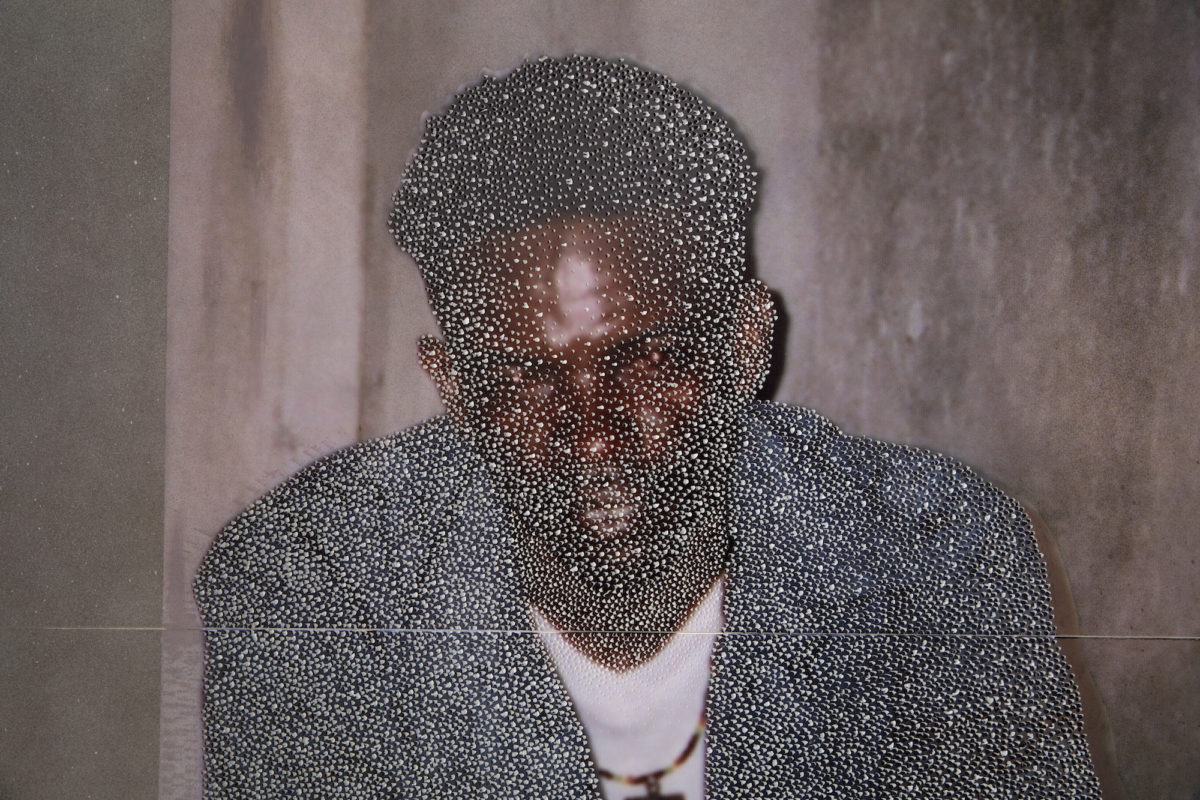

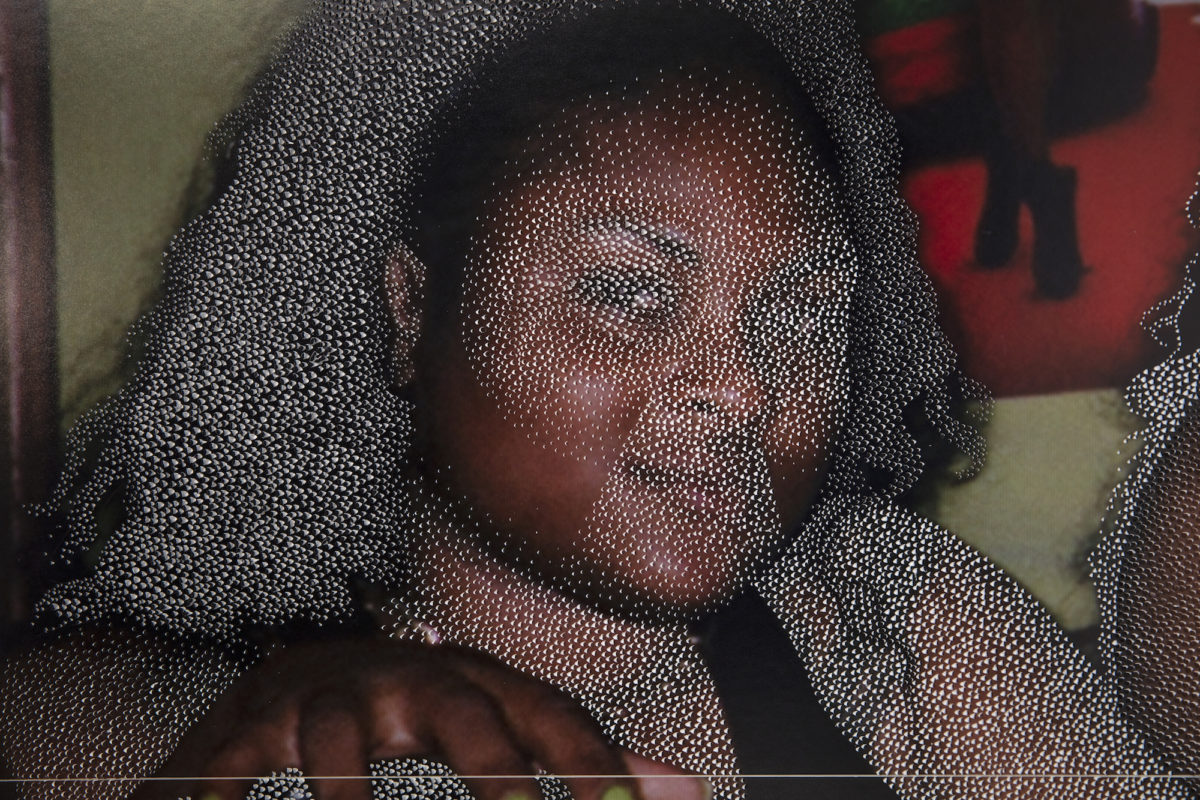

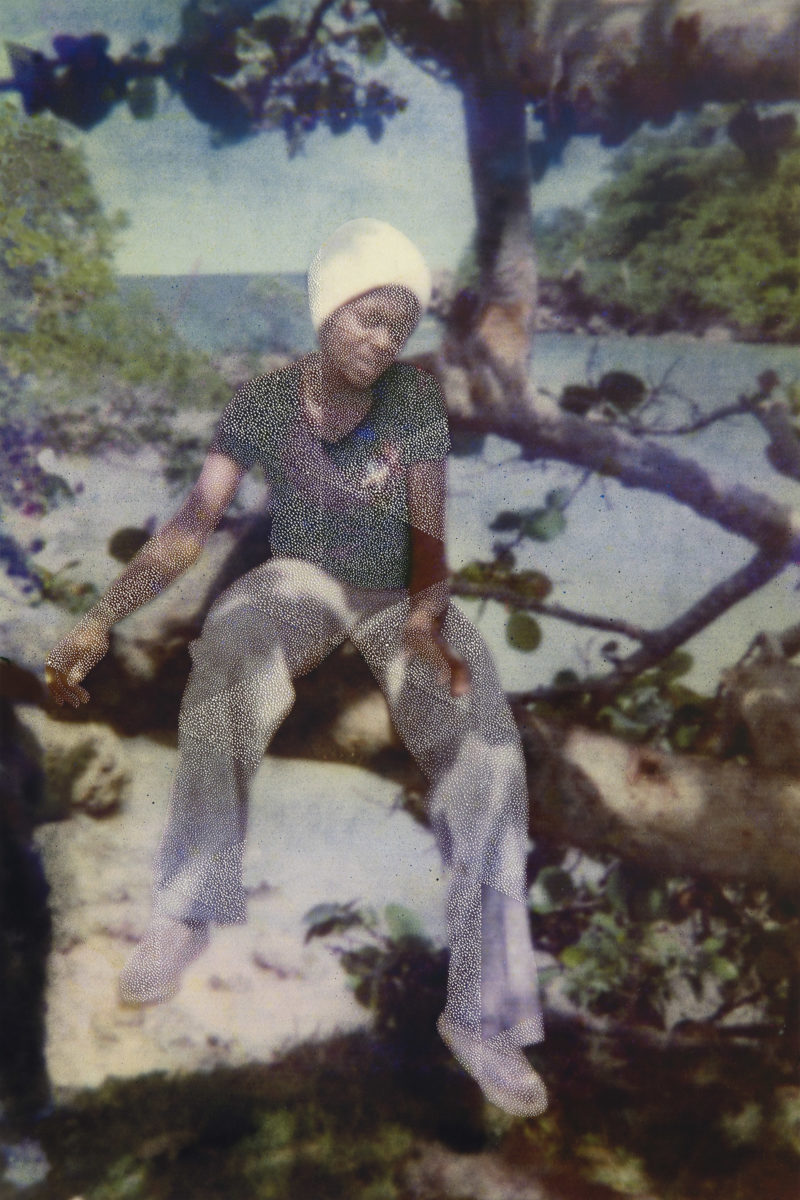

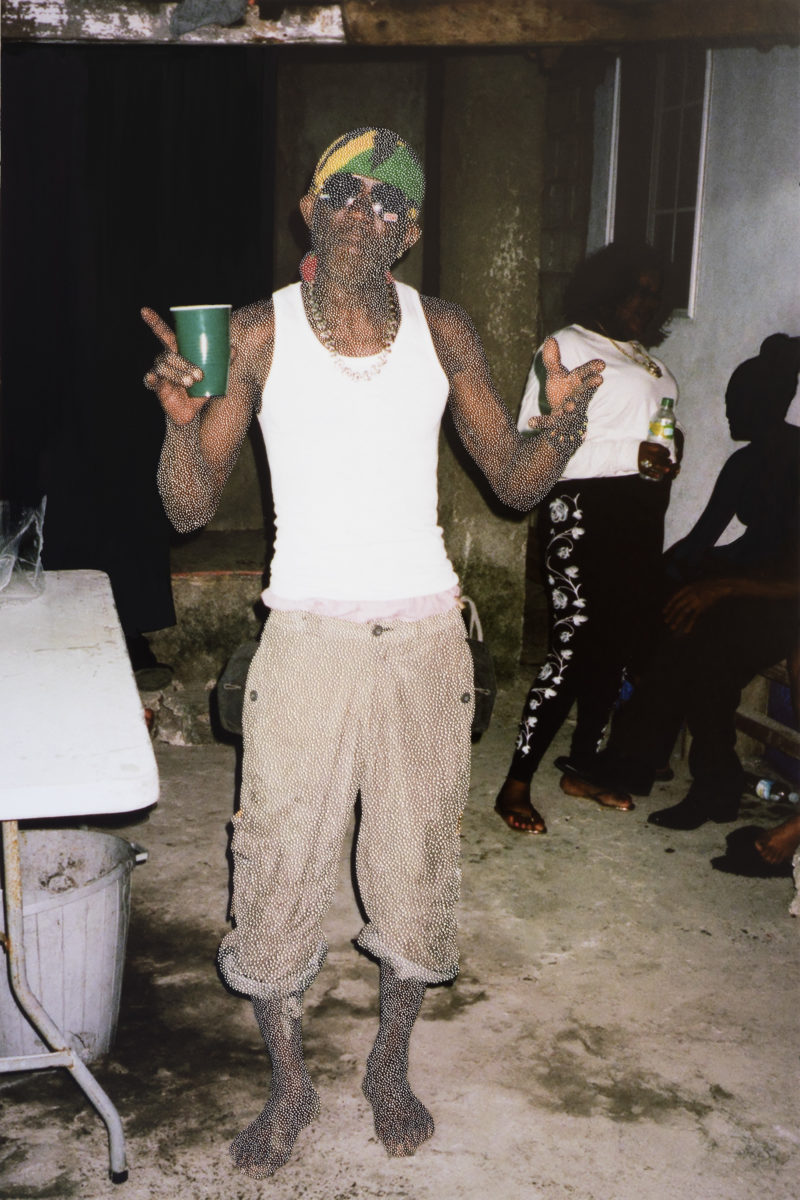

Later that year he returned to the UK especially to see a solo show by abstract painter Mark Bradford at Hauser & Wirth in London. Smith’s work shares a textural idiom with Bradford’s vast, Rauschenberg-inspired canvases in that both layer their surfaces. But where Bradford builds outwards using paper, Smith uses a picotage technique to pick and partially remove tiny sections of the prints to create a dotted, almost disappearing effect. “The scales mean that there’s a lenticular quality to how the image works, because when you walk in front of it, it kind of shifts,” Smith explains. Exposing the board beneath the print in a single direction allows the images to almost protrude towards the viewer, while simultaneously appearing flattened from other angles.

- Paul Anthony Smith, Untitled [details] (left; centre-left; centre-right); Dog an Duppy Drink Rum [detail] (right), 2020-1. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

We discuss the acclaim afforded to the works of Titus Kaphar over the past year, which take this idea of creative subtraction to its extreme by completely cutting subjects from the canvas. Is Smith’s technique akin to this—or does he view surface manipulation as a kind of addition? “In this show, I’m revealing a bit more to the audience than I usually do,” Smith says of his sparser picotage in Tradewinds. Whereas his previous exhibitions have focused specifically on the Windrush era and modernism, the latest Jack Shainman show is more domestic and intimate. “I’m giving you a bit more insight into who I am rather than picking away at my subjects as much. I’m using various patterns of disguise.”

“I’m giving you a bit more insight into who I am rather than picking away at my subjects as much. I’m using various patterns of disguise”

This impetus has allowed Smith to synthesise this cultural moment—one in which Black death is ubiquitous—into these new works. The result is a mixture of memory, commemoration and quiet contemplation, away from the carnival and music-oriented impulses of previous exhibitions like Junction (2019). In Untitled (Dead Yard), a man walks down a nighttime street, arms outstretched and wearing an unknowing smile. Smith’s picotage resembles a superimposed metal gate around him, which seems to lift the subject from his quotidian surroundings. “I was trying to be a bit more vulnerable with my subjects and show more human nature,” Smith explains. “These calm candid shots rather than the more performative aspects of Junction, which was about music.”

- Both: Untitled, 2020-1. © Paul Anthony Smith. Courtesy the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery

Although not addressing the pandemic and 2020’s racial justice movements in a photojournalistic sense, Smith views his Black and diaspora subjects as part of wider historical moments, despite focusing on this vulnerability—and the ritual and communities which enable it. Two untitled shots show the simple closeness of a friendly gathering: shared drinks, brightly painted nails and open shirts for the thick Caribbean air. “We come on earth for such a short time, and we are celebrated a few times in our lives,” Smith reflects. “I think death is much closer to us than we think—but there’s something amazing about it.”