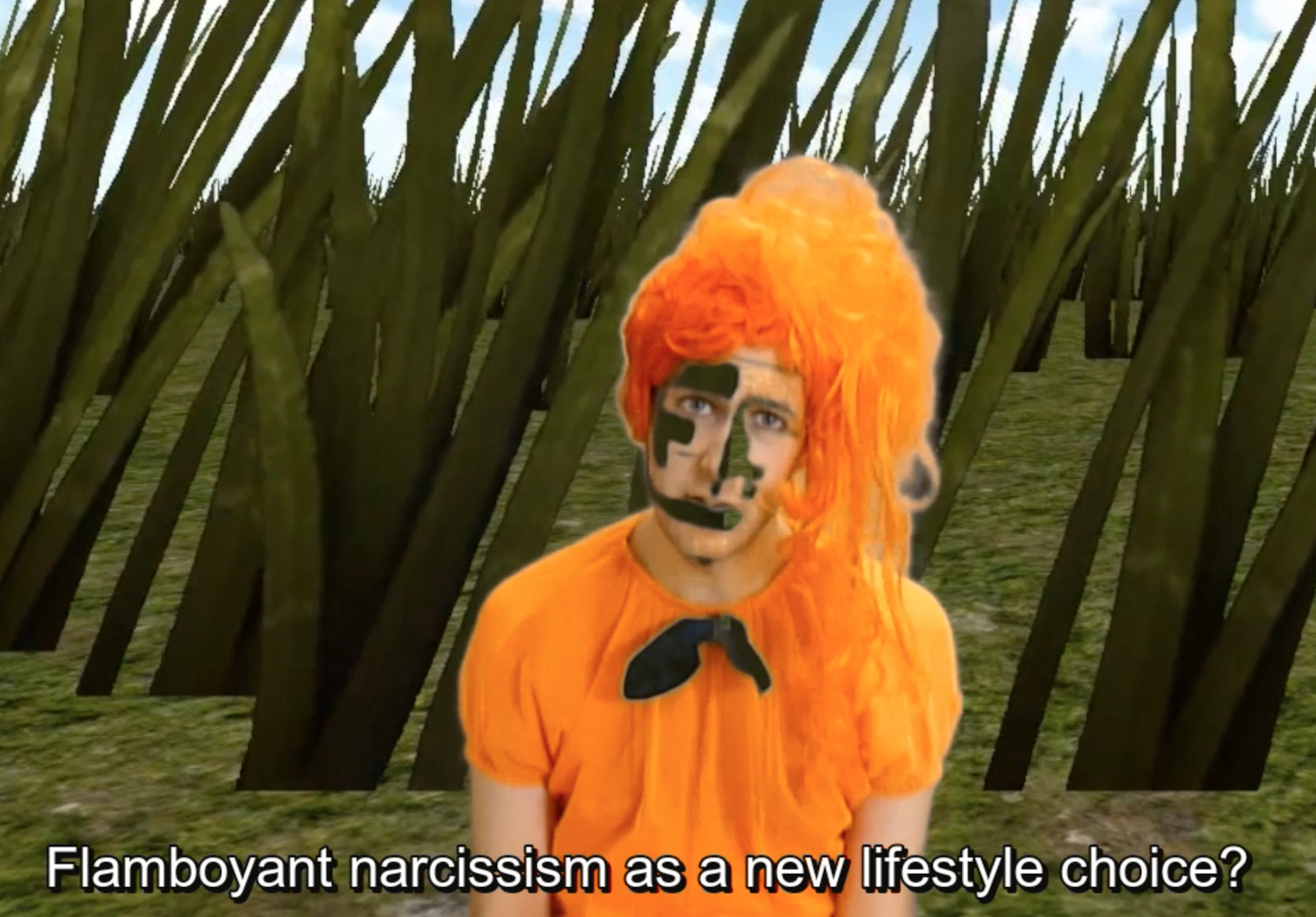

Paul Kindersley loves to dress up. Fantasy, drag and immersive performance come together in the British artist’s high-energy work, which draws a line between art and life. In his early homemade films, makeup tutorials are given a surreal spin as Kindersley transforms the face into an artist’s canvas, layering acrylic paint with face paint with, say, a lipstick. Drag spills over into Kindersley’s everyday life, where he is likely to be spotted sporting a brightly coloured wig on the streets of London. He has exhibited and performed across the UK and further afield, including as Charleston, home of the Bloomsbury Group

, where he was commissioned produce a major film work inspired by Virginia Woolf’s Orlando.

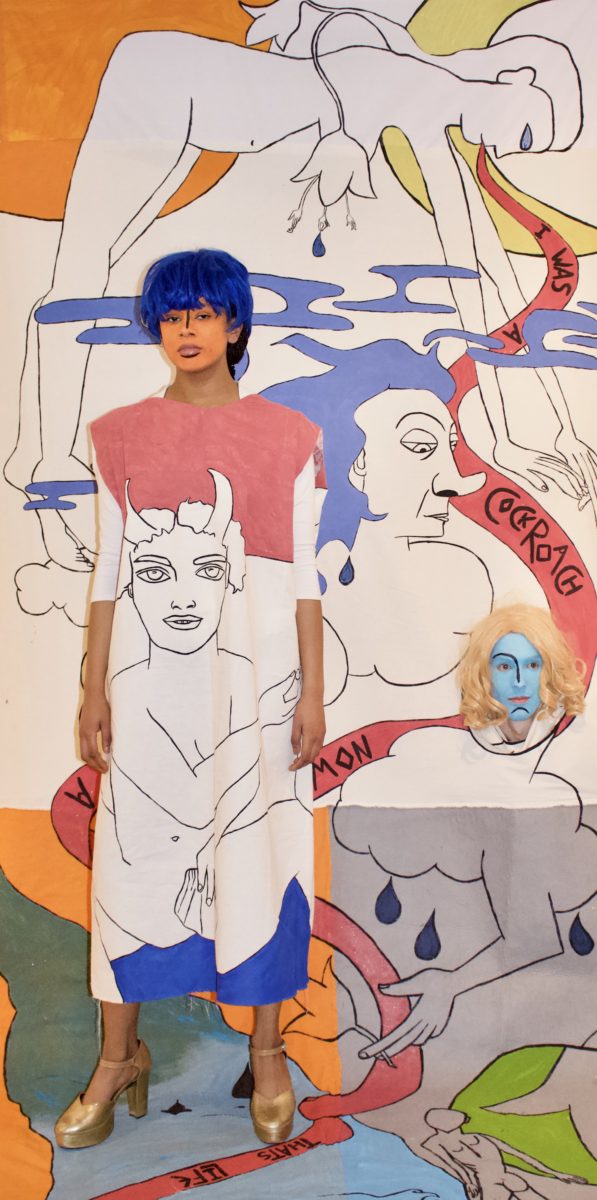

Kindersley increasingly works with a larger cast in his video and performance works, such as in Ship of Fools, a play written by the artist and inspired by a Hieronymus Bosch painting. The Burning Baby, his latest and most ambitious film to date, sees him and a group of professional and non-professional actors inhabit the Scottish island of Eilean Shona to shoot a psychological horror fairytale. The film is a surreal queer fantasy that investigates landscape, identity, family, sexuality and death. Kindersley also sketches and produces regular drawings as part of his artistic practice, many of which form the backdrops to his live performances. Vivid, all-encompassing and theatrical, his work moves easily between multiple spheres, from fashion to fiction, humour to horror, and from fantasy to reality.

Your performance work often features yourself, and you tend to make use of props, costumes and wigs as part of this self-presentation. How important is drag and gender identity to your work, and how much of yourself do you want to hide or reveal through it?

It’s about hiding and not hiding with it because, although it seems like becoming someone else, I find that through these props I learn so much more about myself. It’s weird that sometimes, when I look back, I realize that I’m actually exposing myself in a way that I never thought I was. I’m not good at having alter-egos, so it’s all just different variations of myself. Even when I’m drawing, they end up being self-portraits, in a way. But I think that’s true for all art. It’s a bit narcissistic. What I like about doing something artistic or creative is that it brings out things that are within all of us. They’re not necessarily nice, or good, or beautiful things, but we all have them within us and it’s just about accessing them.

I think drag is very basic and that every decision that we make about the way we present ourselves is sort of drag. During lockdown I’ve been at my parents’ with hardly any clothes, and I do feel like I’m in drag now because I’m basically wearing the same tracksuit every day, and to me it almost feels alien in my presentation. I always find the weirdest thin—especially when you’re in London—is all the men in suits. To me that’s that exemplifies drag because you’re really trying to make a specific impact with your clothing, and it’s specialized and ridiculous. So, for me, drag is just a dressing up— from the very basic getting dressed each day right through to trying to give off a really specific vibe.

“I’m not good at having alter-egos, so it’s all just different variations of myself. But I think that’s true for all art. It’s a bit narcissistic”

Dressing up has always been such a massive thing for me from a young age. It was one thing I could do relatively easily, and I used to do it at home. I would go to the jumble sale at the church and come back with gowns and all sorts of things for my one pound coin—you could buy anything. I remember realizing the power of clothes and things when I was younger. I used to really want to wear dressed and my parents didn’t mind, but people at school were really quite horrible, including the parents. So you realise really early on that this is not what you’re supposed to do. I do wish that everyone could just wear what they want. It baffles me that there’s so much policing by people of themselves.

Makeup is another feature of your work, and seems to connect your drawings on paper with the possibility of the face as a canvas. How do you relate your drawing practice to your live performances and films?

It’s all connected. For me, whether I’m doing drawings or performances, and they’re all different iterations of the same thing. There’s never one artwork that’s necessarily “the thing”. Drawing is something I’m always doing, and it got to a stage where making more physical things seemed a bit pointless. So I just literally started drawing on myself. And it just felt like there was so much freedom in the way you could just wash it off and there would be no physical remnants. It felt really liberating that the artwork didn’t have to be something that would clutter the world and fill up space.

I’ve always been interested in makeup, but at first I was just painting my face with things that I had lying round the house, like acrylic paints and face paint. And then people started sending me actual makeup, so I’ve now got a collection of people’s old makeup and stage makeup. But there’s something about just using everything—like you said, the face as a canvas—and just trying everything out. Sometimes you just have to be spontaneous.

It connects back to drag and how we can tell stories by adorning ourselves in different ways, and how we can understand our purpose. We’re so concerned as well about the impression that we give and what other people think of us. I play into it so much but it’s one of the things that worries me, and that stresses me so much about life is that that as individuals. It takes up such a disproportionate amount of our mental time and energy and probably our mental health, when we could be experiencing other joys that people have to offer that aren’t exteriors. But then, I think that dressing up and painting and performing, and trying on characters, is a shortcut into an interior that I can’t access easily in myself just by being me.

YouTube has been an important part of your work, both in terms of taking direction from the style of the amateur tutorial video and in making use of the platform to share videos yourself. What is your relationship to it now?

With the amateurism (I’m trying to think of a better word!), it’s about harnessing the moment and the excitement and the joy and the making: the actual physicality of doing it. I like to have everything set out, so that within it we have even more possibility to explore that impulse. Now, especially if you’re working with other people, you need to be in an environment where you can heighten your ability to get in touch with an intuitive and impulsive moment.

But with the YouTube tutorials, again it was at a time when I was just thinking there’s so much stuff in the world, so physically I didn’t want to create more things. And also, there was something about storytelling that has always been very important to me. I believe the highest form of art is other people telling and embellishing stories. I’m quite into the idea of fake-news and post-truth—before Trump and everyone started. I like the idea that people’s stories can be completely embellished and almost false but, because of that, so many truths start to come out—like the way people choose to tell myths and legends and pass them on.

“I believe the highest form of art is other people telling and embellishing stories. I’m quite into the idea of fake-news and post-truth”

I would record my videos on my webcam and computer. It was just an instant thing, and there would be basically no editing so I just had to talk non-stop. It’s a form of storytelling. But the thing I liked most about YouTube is that the people watching were basically in the exact same situation as you. You were one person sitting in front of your camera and each person watching you was alone in front of the camera as well.

- Left: The Image, 2018. Right: The Burning Baby, 2020

What has it been like to expand your video practice to larger scale films, with a bigger cast than just yourself? What have you learned from the experience?

I like it to be an intimate group where we’re all together and living the experience as well. Through film history there are people like the Dogme 95 who tried to do this as well, where everything on camera has to actually happen. That was the case with my latest film, which we shot on a Scottish island that was basically uninhabited. While we were filming, we had to eat and do all the normal things, everything together. It was almost like trying to create some sort of utopian commune for a really short period of time and if you’re all together and you’re all striving towards creating something.

We’re all a bit obsessed about what’s real and reality, but I don’t think necessarily that just presenting what you think is real (which is obviously impossible) is ever that interesting. When we’re talking about the truth, people are editing themselves. We live in the world of the hyper-documentary, and you see the way that people are almost documentary-ready. When people tell stories, they’re editing them. I think you have to get away from the edit and just include all the wildness within that. Because, as people, we are confusing and complicated, and also we’re filled with things that we wouldn’t want anyone to know or we wouldn’t want to admit, but actually, it is within us all. It’s more useful to acknowledge we’re not that different.

You’ve been very busy during lockdown on isolation projects, from daily sketches to a unique way with your Lego constructions. How has this time impacted on your work, and what advice would you give to others looking to explore their creativity during this time?

I’m sharing drawings and it’s nice, although I do a lot of that anyway. But I also like the Artist Support Pledge initiative because it supports a community, and the idea that you can buy someone else’s work—I bought a really amazing painting—and I just thought there was something quite special about that, and also having the direct connection with people and artists. It created an online gallery, which is not actually that new as we mainly access art through the internet, we live in an online gallery anyway.

“Everything that you do is art. You can be creative without having the external pressure”

In terms of being creative, I’ve been helping to look after my niece and nephew, so when they were playing Lego, I thought, “Well, I’ll just sit and play Lego with them.” And it’s just nice to do something that you don’t necessarily think is creative. But, really, everything is creative, and it’s also interesting to realize that everything that you do is art. You can be creative without having the external pressure. It’s been widely talked about, and I think there’s this new pressure of, “What? You’re not doing anything in your lock-down? You’re not learning how to knit or baking banana bread. You’re not being productive?”

But I think we probably need to do the opposite and just stop trying to be productive. I think that’s probably the most useful thing you can do right now, because in daily life we have to be productive every day, whether we want to or not. So this maybe is a good time, if you’re not still going to work, to actually just work out what happens when you don’t have to produce or make. With my Lego, when I wake up in the morning, my nephew has always smashed it. It takes away the pressure, even when I make something really nice, he’ll have pulled it apart to make a car or something. But I think it just helps to make stuff—I know it’s a cheesy thing. The more you make, the better it is. And I don’t mean necessarily physical things. Just making.