Elephant contributor Bella Butler seeks to understand her experience of early 20th century artist Paula Modersohn-Becker’s body of work from her recent retrospective at the Neue Galerie in New York. More specifically, the writer explores why she was moved by the artist’s drawings above all else.

The intensity with which a subject is grasped (still lifes, portraits, or creations of the imagination) —this is what makes for beauty in art.

– Paula Modersohn-Becker [ca. March 1905)

Earlier this month I trekked to the Upper East Side from Princeton to visit one of my favorite galleries—The Neue Galerie—to see the retrospective that was about to close on Paula Modersohn-Becker (1876-1907). Until now, Modersohn-Becker, despite being a major figure in the history of German Expressionism, had never been the subject of a major retrospective in the United States. It felt thrilling and novel, then, to see the work so thoughtfully highlighted.

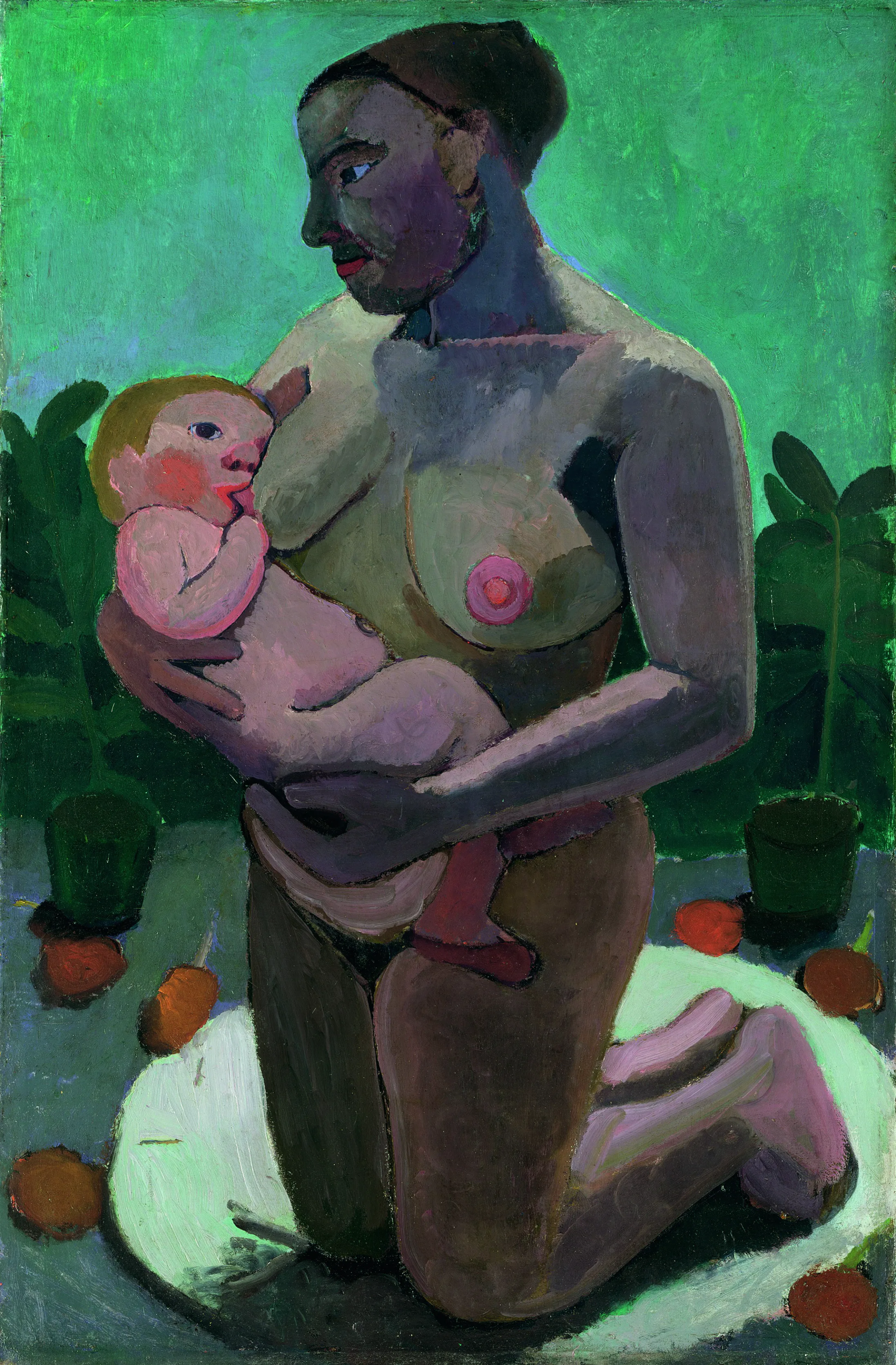

A painter first and foremost, Modersohn-Becker’s pieces are quaint, sometimes uncanny, and with regards to content, radical. They depict life and landscapes alike from the influential artists’ colony in Worpswede, Germany, where she resided along with other seminal artists and writers from the time—among them, her partner Otto Modersohn-Becker and friend the famed writer/poet Rainer Maria Rilke. I was moved by her paintings, in the sense that I recognized their significance amidst the male point of views on life, children, and the female psyche; they are flat in composition, expressionist in stroke, and evocative in the plainness of their subject matter, especially her self-portraits, known as some of the first nude Western female self-portraits. But I didn’t leave thinking about her paintings. I left thinking about the charcoal on paper: her drawings.

The layout of the show is such that you begin in the room of her drawings. Out of the four rooms, this first room is the only one dedicated to them. Materially speaking, this felt logical. The drawing is often considered the nascent stage for works of art. It is the first step of many. It is the blue-print to the masterpiece. Pedagogically, the artist typically draws before they learn to paint.

However, I would argue that the degree of vulnerability and proximity to the subject in Modersohn-Becker’s drawings place them higher in a hierarchy of alternative criteria, criteria that is founded upon the content’s relation to the ontological and emotional. What if they were not considered the “first step” in her artistic career, but masterpieces in themselves? And could the spatial organization and orientation of the show affect this?

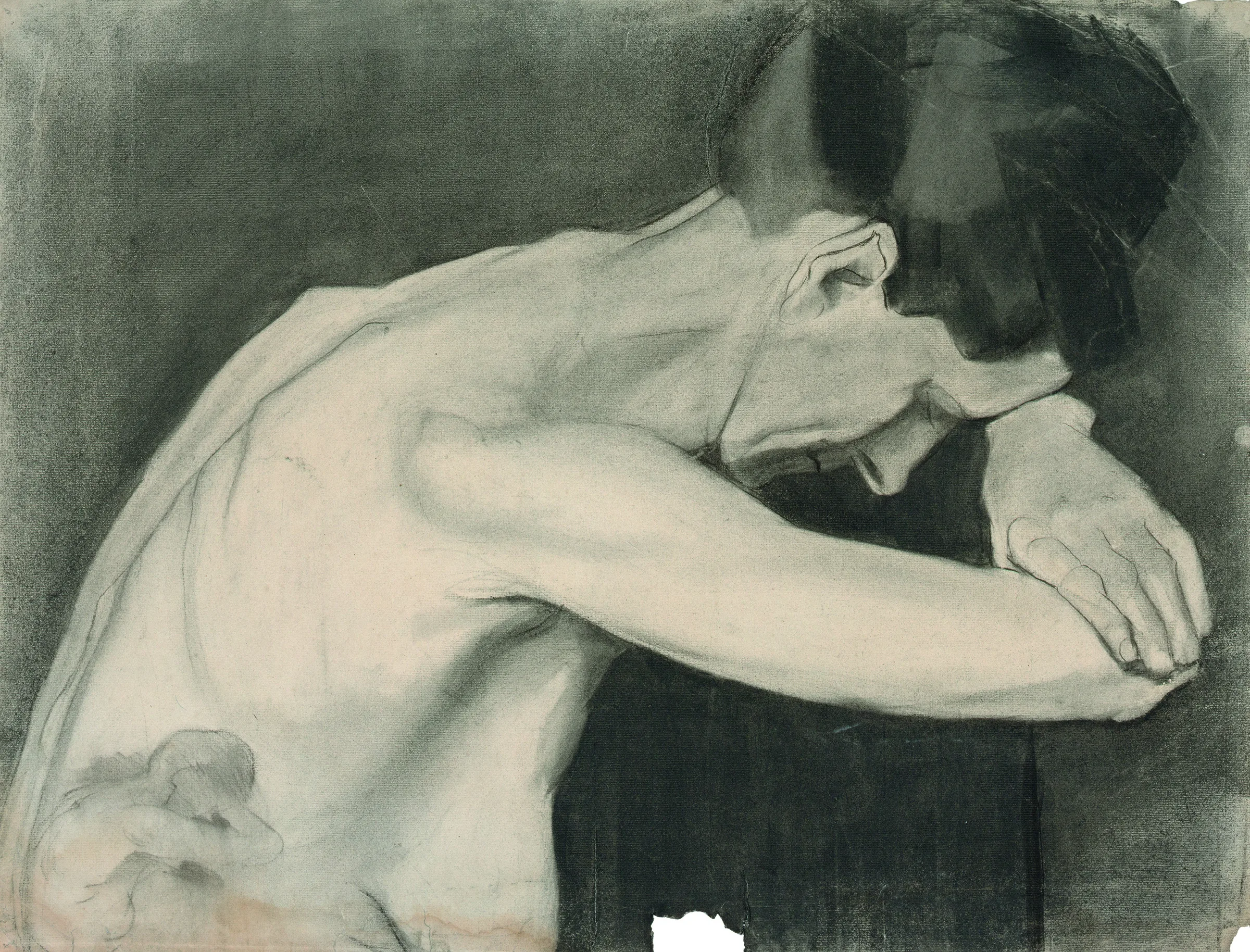

The drawings displayed in the show are a mix of portraits of everyday people and nude figures. Clothed or not, Modersohn-Becker’s portrayal of the human form is consistent: it is empathetic, patient, and for lack of a better phrase, deeply attuned.

This empathetic approach to the human figure is epitomized in Upper Body of a Woman Leaning toward the Left, Alongside a Small Sketch of the Same Motif (1898). In this charcoal drawing, Modersohn-Becker depicts a woman bent over and resting on her own arms. Her eyes are closed and the background is shaded entirely behind her. The elimination of an external landscape, paired with a closing of the eyes, suggests an inward turning on the part of the subject. Her body is present for the artist, but her mind has retreated. The lines around her face and mouth express fatigue, accompanied by the pull of her own breasts. The movement in the drawing has a gravitational pull downwards, the direction of flat ground, of earth. She is called by a surface on which she could lie flat. But, as Modersohn-Becker captures, she is not able to reach where the contours of her body, skin, and muscles are pulling her. Instead she is here, hunched over, stuck in a posture of that fatigue, able to be drawn by the artist.

The emotional intimacy of this drawing is something with which her paintings cannot compete. The medium of drawing, and especially the use of charcoal, allows for both gestural and temporal proximity to the subject. The hand to the paper is all that is required to “capture” the state of the figure, as opposed to painting, which requires the stages of color creation and manipulation and layering. In this way, these drawings portray an inherent indexicality—the implication of the artist’s physical hand, physical body, on the page where it has produced something. It is as if, in these drawings, she is reaching out with her hand, to connect with the subject. Additionally, the material of charcoal necessitates another degree of intimacy between the body of the artist and the page, as one must rub with the finger to blend and shade; the mediating object of the drawing instrument is therefore momentarily eliminated.

Upper Body of a Woman Leaning toward the Left is also reflective of a non-voyeuristic approach to the subject, present within all of Modersohn-Becker’s drawings. There is nothing fetishistic about the bodies she depicts, despite many of them being in the nude. As I floated through the space, a feeling of honesty hung in the air, hovering within the aura of the mounted pictures.

What I have come to after spending some time with these drawings is that the “honesty” stems from her ability to communicate the interiority of the subject through the exterior of the body. This devotion to interiority is most readily accessible in the form of the small figure in the bottom left hand corner of the aforementioned drawing, that sits within the figure of the full size woman. Because of her analogous posture, the viewer feels they are privy to an internalized version of the woman, the “real” version, dare we say. We can see the vague outlines of hands covering her ears, a gesture that relays a feeling of: this is too much. And Modersohn-Becker’s compositional choices and charcoal allow the woman to say this.

tempera on canvas mounted on wood. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin,

Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Nationalgalerie Berlin. Photo: © Paula-Modersohn-

Becker-Stiftung, Bremen.

While this interiority is present in her paintings, we are still materially further from it than with a drawing. With a painting, it is as if we must scrape through layers and layers of paint to reach the core of the human (even if there is no real biological ‘core’ in a painting of a figure), whereas a charcoal body reminds us that the skin is but a mere surface for what lies below. It is a visual manifestation of the subjectivity that lies beneath it.

Formerly at the Neue Galerie in New York, the show Paula Modersohn-Becker: I Am Me opened at The Art Institute of Chicago on October 12th, 2024, and will remain there until January 12th, 2025.

Words by Bella Butler