The Brazilian artist Paulo Nimer Pjota (b. 1988, São José do Rio Preto) has had a meteoric rise since his breakout exhibition at Mendes Wood DM in 2012, achieving critical acclaim for his engrossing paintings and sculptures that combine an elysian visual vocabulary with a distinct approach to technique and materials. Some of Pjota’s latest works are on view in the space’s New York outpost in Na Boca do Sol (January 27-March 2, 2024) and, following the exhibition, the artist will have a solo presentation at Art Brussels in April and will be featured in the 38th edition of the Panorama of Brazilian Art biennial at the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art in October. Pjota has also recently joined the New York- and Los Angeles-based François Ghebaly Gallery. In an interview with Elephant, Pjota shares some thoughts on the beginnings of his practice, his process and the pervading presence of myth and mysticism in his work.

You began your practice as a graffiti artist. How did your later practice develop, and how do those early experiences continue to influence your work?

I was actually painting on every possible surface I could find until I stumbled upon graffiti and hip-hop culture at the age of twelve. There were no museums or galleries in Rio Petro, where I grew up, and the only rebellious way to think about art was through graffiti. The main characteristics that I brought to my work don’t come directly from graffiti itself, but from the experience of living in Rio Preto and experiencing the popular architecture there.

You began creating your own pigments early in your career. Could you please talk about your process and the genesis of this part of your work?

The beginning of my research into pigments also stems from my hometown. Initially, I used the same pigments that are used for painting the façades of houses. The use of tempera as the first layer in the paintings actually comes from techniques used in cal painting, which involves mixing cal powder with pigment and water, resulting in a thin paint. The colours are usually lighter and more subdued compared to acrylic paint. I apply tempera as the first layer in my paintings, using the same principle but mixing powdered pigment with transparent varnish.

Over time, I had the opportunity to visit several countries such as Morocco, Mexico, and others in Europe, which allowed me to expand my research and explore the possibilities of using and composing different types of pigments. In Morocco, for example, the use of mineral and natural pigments derived from plants and stones for house painting is very common, similar to the use of lime paint in Brazil. The perspective in my work is achieved through layers of different types of paint: tempera, oil, and acrylic.

Your current exhibition at Mendes Wood DM brings together paintings that are both enigmatic and evoke art historical and mythological references, organised chronologically from day to night. What influenced some of these works?

I divided the paintings in the exhibition into phases of the day—morning, afternoon, evening, and their tonal variations—after the music of [the Brazilian singer] Maestro [Arthur] Verocai. The three nocturnal paintings evoke mythological and personal passages in a way that this division becomes metaphorical. It takes on a character of dreamlike intoxication, where the perspectives of the paintings and their elements, like flowers and beings, blend in the pictorial plane, expressing a fantastical and spiritual thought drawn from fables and myths.

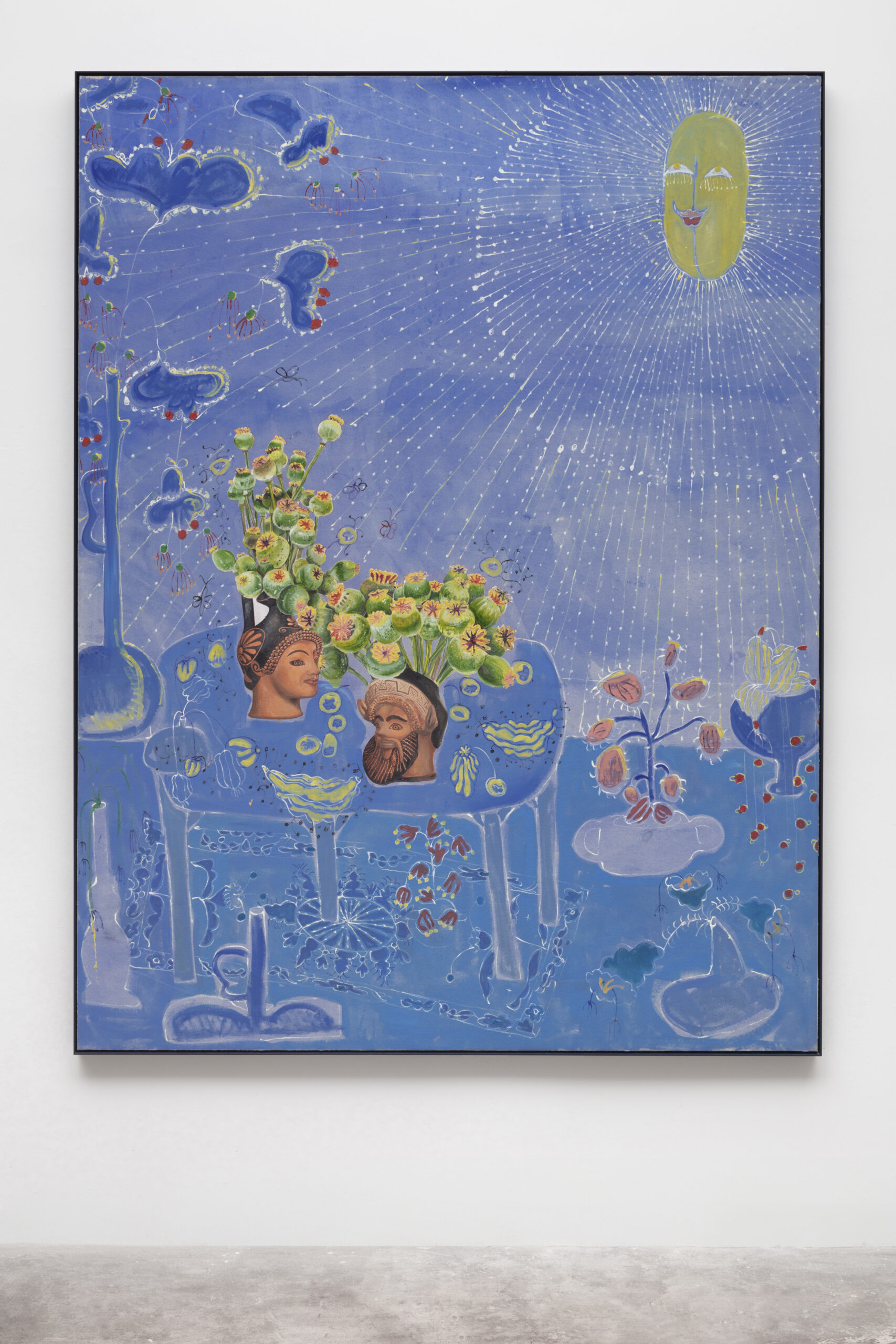

In Noite com Dionísio, for example, I refer to the Greek god who possessed knowledge of vital cycles, festivities, activities related to material pleasure, insanity, religious rituals, theatre, and wine, as he was knowledgeable in its preparation and, primarily, intoxication. Dionysus appears veiled by the twilight of the blue night, with his classic crown of grapes and his wine goblet. Alongside him in another painting, Noite com Julia, I depict my wife Julia as a fantastical woman blending with the flowers and leaves on her body. I thought of the magic of Artemis when I painted her.

You’ve titled the exhibition Na Boca do Sol after a song by Arthur Verocai. What does this song symbolise to you?

I had the opportunity to attend two Verocai concerts in Brazil, the last one in 2023. Both times, when he played “Na Boca do Sol,” I was moved to the point of tears. This song reminds me of my grandfather speaking about his train journeys from Rio Preto to Rio de Janeiro—the countryside sun scorching even in the shade, the railway crossing the city, and the sound of the train whistle. To produce this exhibition, I had to delve into my inner self, revisiting artworks from when I was twenty years old, something I hadn’t done in a long time. I connected with this return to childhood, with my dreams, and with the realisation that I have achieved them.

I spent six years immersed in this series of works, discarding many paintings until I found this state of mind. Realising that I found what I was looking for on this journey back in time to my adolescence, experiencing life on the streets, noticing the nuances of the countryside, and waiting for the train to stop so I could paint it fills me with deep emotion. I realised that no movement was random and that painting is a timeless construction.

The works contain deeply spiritual elements. How does your spiritual practice inform your work in the studio?

For me, painting is not just a creative act but a spiritual practice that I’ve come to understand over time. It’s found in the rituals of the studio—the need to listen intently to what each painting demands and the trance-like state induced by the brush’s touch on the canvas. There’s a unique level of concentration and focus that each painting requires; within my body of work, this process becomes a kind of mantra. The repetitive motion of the brush on the canvas and the fluidity of the strokes draw me into hours of uninterrupted immersion, where thoughts of anything else fade away. It’s a meditative state reminiscent of my spiritual practices outside the studio, but here, it’s even more intimate.

What was your day-to-day like in preparation for the exhibition? Was there anything that had an impact on your approach and the final works?

I go to my studio in São Paulo from Monday to Friday at a fixed time, and I try to paint every day or think about what I will paint. For this group of works, I looked closely at the construction of space in Flemish painting, exploring still life, vanitas, gardens and interior scenes; landscape construction in Japanese prints and their verticalised perspective, composition, and appearance of fantastic beings; cartoons; religious altars; Greek, Mesoamerican, and Brazilian culture.

Your paintings and sculptures often employ salvaged or found materials. What is your relationship with these materials?

Yes, that was quite common in my previous works prior to this series. The choice of these found iron sheets is inspired by the architecture of the house façades, with their worn and weathered gates. These sheets bear traces of time, which greatly interests me as I envision the cultural and imagistic structure of my work as timeless. These sheets are filled with inscriptions, dirt, and colours that came before me, much like the painted images. As I mentioned, I’ve been heavily influenced by architecture. In these recent works, I’ve set aside the iron sheets because this group of paintings has a more dreamlike character inspired by dreams, myths, and fables. The discussion is less rational and geometric than before.

You’ve cited Joseph Campbell as one of your greatest influences. What were some of your earliest encounters of Campbell’s work, and how did it resonate with you?

The first time I encountered Campbell’s work was by chance. While researching symbolic relationships, I stumbled upon his interview titled The Power of Myth on YouTube. It was then that I realised that what I was thinking not only made sense to me but also had a broader resonance. For Campbell, myth is not merely a fantasy or something unreal, which is a conception that often prevails in the minds of Westerners. He argues that myth is, in fact, a key to unravelling what humans have in common—a calling for mysteries and the enigmatic. It is from this understanding that the concept of the monomyth arises, connecting different periods of time and spaces in diverse cultures that never intersected. This thinking was fundamental to my research and is how it manifests in my pictorial work.

What I do is a combination of historical elements that share aesthetic and meaningful similarities, often outside Western standards. In my most recent works from 2023 and 2024, this approach manifests in a different way. While mythological patterns are still present, I believe that now the subjective power of myth is more evident than its symbols. In these works, the painting itself becomes the myth, evoking dreams and transcendence. There is a new layer of subjective meaning that arises not just from the object but from the work as a whole. The painting becomes a portal.

Written by Gabriella Angeleti