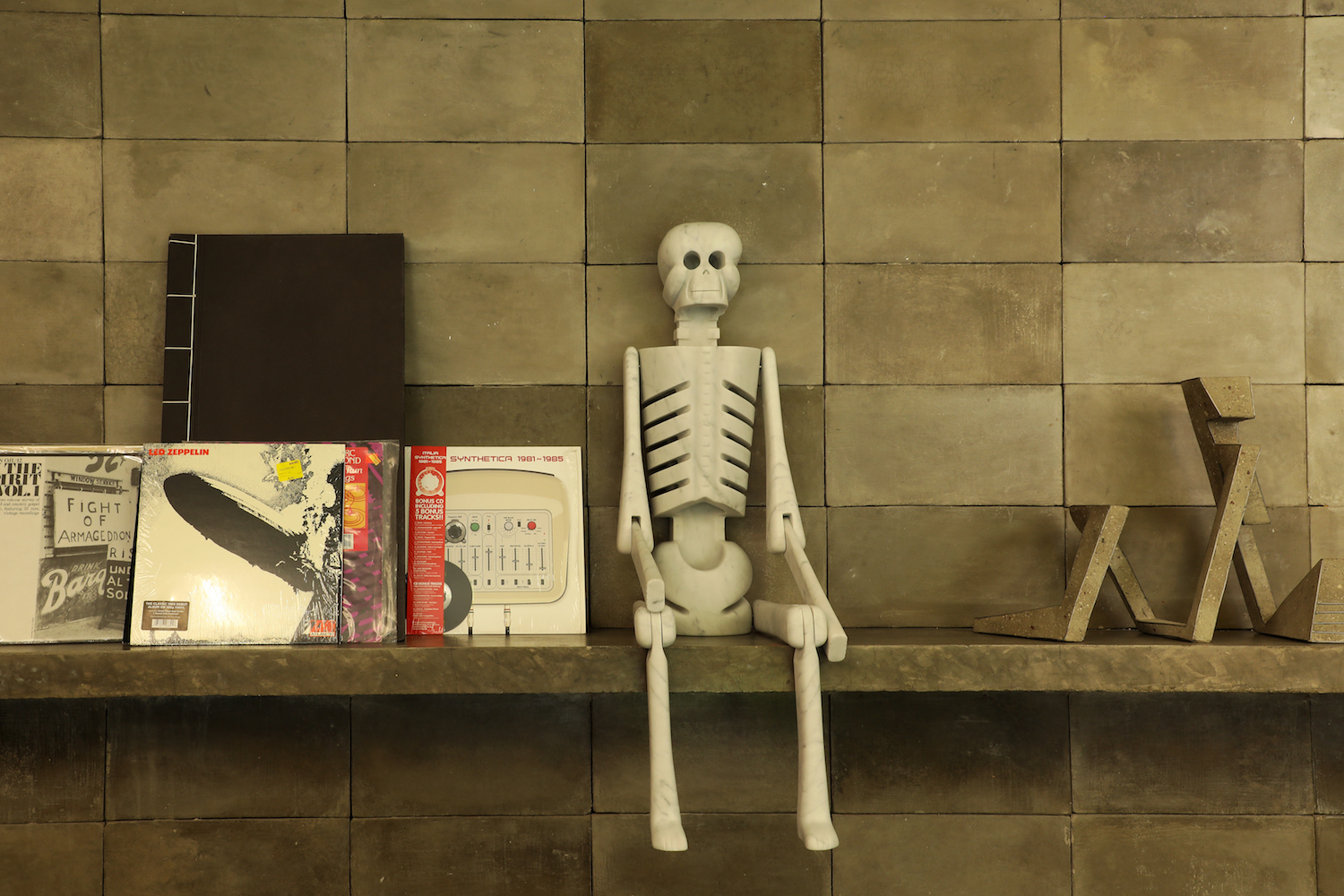

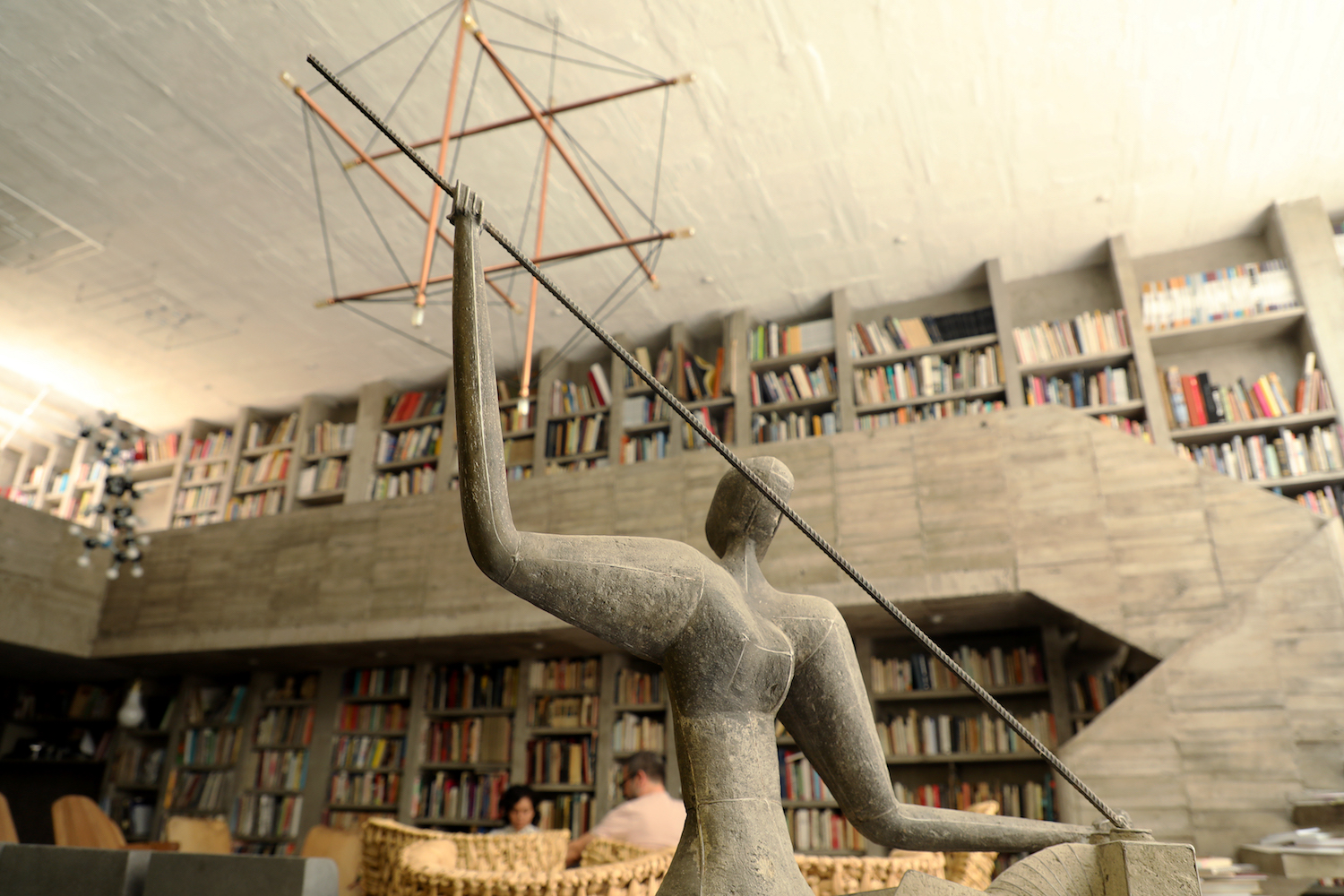

If books make a home, then Pedro Reyes’s Mexico City abode is the most inviting dwelling of all, filled with thousands upon thousands of titles. The vast, multi-storey library dominates the self-designed space, built in homage to Mexican painter and architect Juan O’Gorman who was born in this same neighborhood, Coyoacán. The local history and culture of his native city infuses Reyes’s work, most clearly in its open and participatory nature. His is a varied practice, moving easily between sculpture, performance and video to enact a critical socio-political position on the modern world.

Reyes brings activism to the gallery in projects such as Disarm, shown at Lisson in 2013, in which remnants of weapons, collected and destroyed by the Mexican army, were used to create mechanical musical instruments. In another project, Palas por Pistolas (2008), he melted down guns into shovels, intended to plant trees in cities around the world. In 2016 Reyes presented immersive exhibition Doomocracy, in the Brooklyn Army Terminal in New York, which made use of the tropes of the fairground haunted house to explore contemporary political anxiety at the time of the US presidential election. His most recent exhibition at Lisson’s London gallery this April, he presented a fictional museum of sculpture, creating an totemic array of figures from stone, marble and steel, suggesting that history can be fluid and alternative stories, heroes and icons can and should be celebrated.

Back at his enchanted, book-filled home in Mexico City, Reyes opens up about the importance of inclusivity, social activism … and, of course, the simple pleasure of reading.

While you explore the formal language of sculpture through materiality—be it using plants, weapons, volcanic stones or marble—each piece is completed by the sound it produces in performance when it is played. What is your relationship with ephemerality?

I work with tangible and intangible materials. The intangible may be the experiences and specific psychodynamics that the artwork can create. That is why I have always been interested in therapy and theatre. Yet I consider both the tangible and the intangible within the realm of sculpture, because is about form. In sculpture, forms are concepts. If you take a material and change its form to make a new concept, you are making sculpture. Pieces are ambassadors of your ideas; objects that are there to exist without your presence.

“I’ve never been someone who can stay in a single field or have a single style. I like to explore, and sculpture is an endless quest”

I am always working in two fields. Participation is a material for me. I relate strongly to Augusto Boal’s idea of the spectator: a spectator who becomes an actor. For instance, I have pieces like Sanatorium where the participants ask a question to an oracle or make a confession, write their own epitaph or propose a solution for a public policy problem. You arrive at solutions that you could not have arrived at by yourself; you create with your ears. It is not so much about what you have to say, but what you can listen to. It’s the same with the musical instruments I do. They are sonic sculptures yet I am not a musician. I don’t know how to play. So I always look forward to seeing what the musicians will do.

Recently I made these lithophones (musical instruments made of stone). The first performances were in Brazil and the musicians there had a very particular way of playing. Later in Mexico I invited Tambuco, a legendary percussion ensemble, and they did the most beautiful concerts, everyone in the room was connected with the experience of the music. It was magical. So often the object and the performance, the material and the immaterial, come together; they need each other to exist.

You also make sculptures which aren’t involved in participation but have more of the classical sense of what we understand as sculpture.

In Mexico we have been carving stone for 4000 years, and it’s a great feeling to be connected with that tradition because there is so much to learn from pre-Columbian art and from modern sculpture in Mexico. Often my themes are political or I make references to writers and philosophers who have influenced me. Yet sculpture is always about the history of sculpture and how you can inhabit space and create a form that will offer you a surprise every time you look at it from a different angle.

It is a passion I cannot hide, and the composition and technical problems that it possesses could keep me busy for several lifetimes—even to the point that I look with certain contempt to conceptual practices. But that’s not really true; I love conceptual art. What I’m trying to say is that I’ve never been someone who can stay in a single field or have a single style. I like to explore, and sculpture is an endless quest.

You designed your home studio in homage to the Mexican painter and architect Juan O’Gorman who was born in this same neighborhood, Coyoacán. O’Gorman in fact was commissioned to build the house-studio of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in the early thirties.

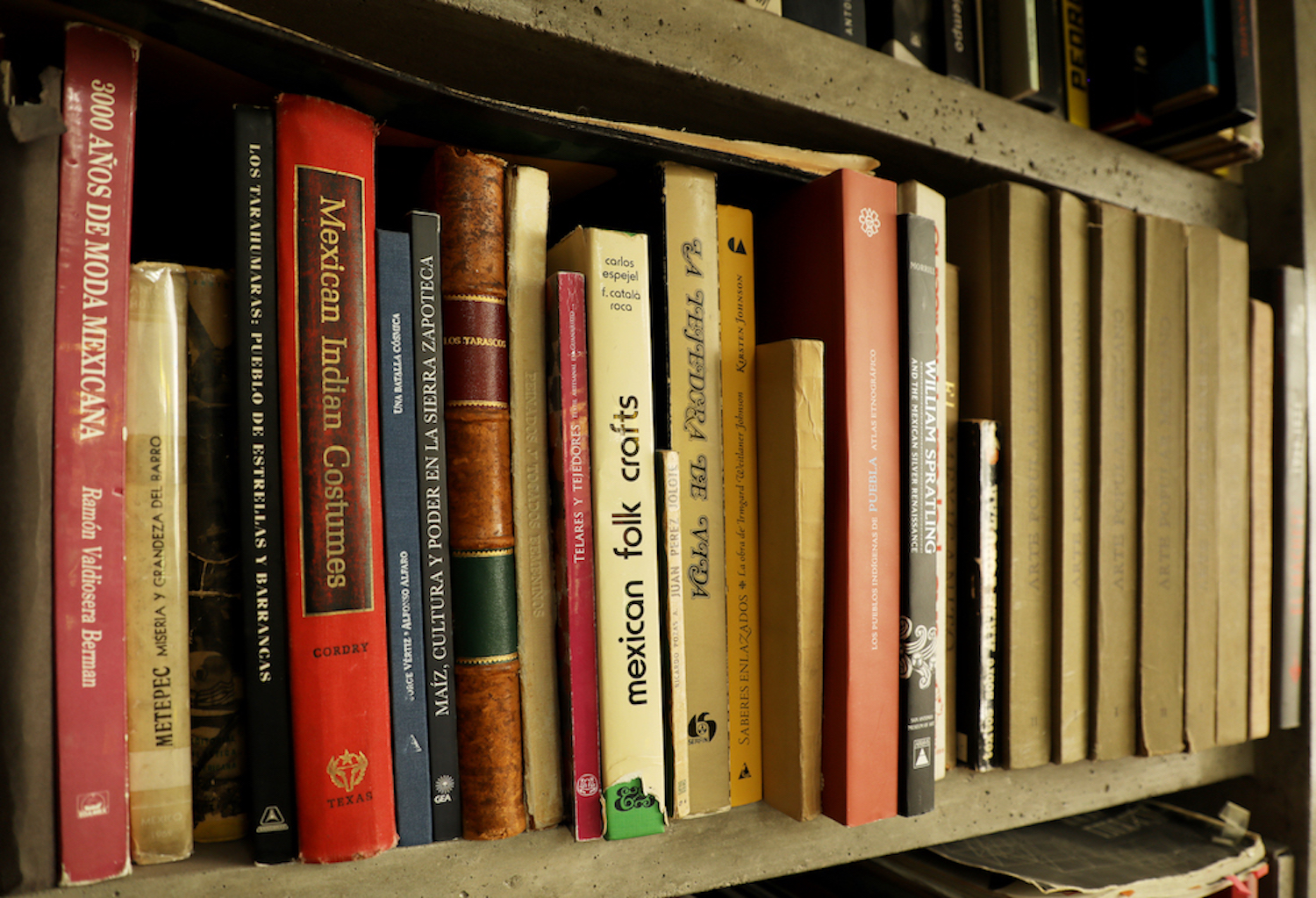

O’Gorman is one of those examples of an artist/architect, like Mathias Goeritz and others who made important contributions both to architecture and art. I studied architecture and never practiced as an architect, so for me this was a kind of opportunity that I could only have doing my own house. All this has been a collaborative project with my wife Carla Fernández and one of the main issues was how to house the ever-growing library. Our neighborhood is a great place with a lot of second-hand bookstores.

The library works as a tool as there is always a lot of research for every project that I do. Every night I spend about four hours rearranging the books that I get, which is where ideas come from. What is in the books is not on the internet. It is very important to have the physical presence of books; it is during the rearrangement process that the serendipitous findings that happen.

What are you reading at the moment?

I am reading several titles by Pierre Guyotat that I got in Paris.

You have been very invested in Marxism and socialism. As an artist whose work deals with social activism, how do you negotiate working within the ideology and economic system of neoliberalism?

In Mexico there are artists like Francisco Toledo who have made really important contributions to the civic life of his city and beyond. One of the reasons he has been able to do major improvements to the city of Oaxaca is because he has a market that allows him extra income to support this cause. I find that example very inspiring. There is a lot of work to do, even if the changes are partial it is important to transform our institutions for the better. Reform is not as sexy as revolution, but I have learned from my mentors Antanas Mockus and Augusto Boal that it is important to find space for agency.

“An idea is only a good idea if others want to copy it or develop it further”

Take the issue of violence in Mexico. A massive 98% of guns in Mexico are bought in the US. And actually, 64% of all new weapons sold worldwide are sold to civilians inside the US. This is more than all the military and police forces in the world combined. That is why the NRA spends so much money lobbying to prevent any kind of gun control. So you don’t need a revolution, you need reform. Inspired by Augusto Boal’s method of Legislative Theatre, I made a project called Amendment to the Amendment, which is a rewrite of the Second Amendment. This workshop is a sort of massive hackathon where the public creates rewrites of the Second Amendment.

My hope is that some of the interventions are replicated. An idea is only a good idea if others want to copy it or develop it further. For example, turning weapons into musical instruments, I have seen in the last few years that a lot of people independently have replicated the project, so even if it is some small examples, I get satisfaction knowing that someone liked it and recreated the idea themselves.

Recently a monograph of your work was edited by José Luis Falconi and distributed by Harvard University Press. This monograph is not only a survey of your work, but you engage in conversations with academics, philosophers, mathematicians, architects, from Antanas Mockus to Manuel DeLanda, Javier Téllez and Lauren Berlant. Can you tell me about the processes of engaging with these particular thinkers and these particular topics from forgiveness to consciousness and the theory of moral sentiments?

The title of this monograph Ad Usum: To Be Used has to do with the fact that half of the projects involve participation, the work was only completed through other people’s input. It has a section of conversations that I had with thinkers that I found to be useful.

It is not enough to identify what is wrong with a system, you have to find solutions, bright spots and case studies where change has happened. I think that a lot of the people who I interviewed fall into this category of cultural agents. I have consulted with Antanas Mockus for the last twelve years, because Colombia has similar problems as Mexico. He created a school of public administration which is very inspiring. It is strange to suddenly find a politician that you trust and believe in. He is not only a politician, he is also a philosopher and a mathematician. He is an extremely creative mind. Augusto Boal, with all the techniques that he came up with for the theatre for the oppressed, a legislative theatre, is also someone I have been inspired by for years.

You have been a prolific artist for close to twenty years now. How has the current political climate, with Trump, Brexit, the alarming rate of femicides in Mexico, reshaped your practice? What is next? Feminism?

(Laughs) I am afraid of venturing into feminism because you can very easily be reprimanded. But I think Simone de Beauvoir was right when she said “the problem of woman has always been a problem of men”. Masculinity needs a major makeover. I am very much interested in toxic masculinity because war and violence have male insecurities at their source. Men who won’t find respect and admiration in life suddenly find reassurance in guns. So a nobody with a gun suddenly becomes The Man, and that is something that has been constructed culturally in movies, TV shows, video games, etc.

“We’re turned on by violence as much as we are turned on by sex”

Even if we would like to ignore it, we continue to be apes. Timewise, we are not that far removed from these ancestors of ours—it’s as if our grandparents were primates. Our brain architecture is built to use violence as if our survival depended on it. In the face of a threat, we release adrenaline and dopamine, two substances that our brain loves, and as soon as these substances reach our neuroreceptors our brains crave more. That’s why when you’re fighting or having an argument you feel a drive to build up the fight—even if, from a rational standpoint, you want to stop. We’re turned on by violence as much as we are turned on by sex.

The problem, in short: the saturation of guns in films normalizes them and reinforces the belief that you need one to survive. Male insecurities run very deep and manifest themselves as militarization. So this machismo continues to fuel the military-industrial complex. It is a very primitive instinct of territoriality, so patriarchy is obviously connected to nationalism.

Going back to culture, I think there could be interesting ways to fix this. You could get a handful of celebrities to change the perception of guns by moving away from trigger-happy roles. If they express contempt for poor storytelling and refuse to act out unnecessary violence, it would only take a handful of stars to get a meaningful dialogue started.

Photographs © Bruno Ruiz Nava