“The art of the past no longer exists as it once did. Its authority is lost. In its place there is a language of images. What matters now is who uses that language for what purpose.”

John Berger, Ways of Seeing (1972)

For the past five years I have been working on a series of exhibitions exploring an approach to making that seeks complete control and mastery over materials, while also pursuing conceptual rigour. The series is entitled Perfectionism, and to date there have been three iterations. The artists are not attempting to create perfect artworks; instead they are attempting to perfect the process, doggedly following a single line of intellectual and physical endeavour. In psychological terms, the pursuit of perfection is viewed as fruitless and ultimately destructive, considered to cause damage to those involved in the quest. I propose a different view: a perfectionism of artistic process, rooted in the desire to understand material properties and their nature, to use materials in a transformative way that ultimately pushes the boundaries of innovation and creative thinking. It is an approach that refers to the ancient practice of alchemy, in bringing together the disciplines of science, art and philosophy, and also seeks to imagine the future. Therefore, in this context, perfectionism is to be seen as entirely positive and productive. I would even go so far as to suggest that perfectionism has the potential to take us from the principles of the Enlightenment, accelerating the human capacity for creativity and innovation, into a liberated future on the planet that we are currently busy destroying.

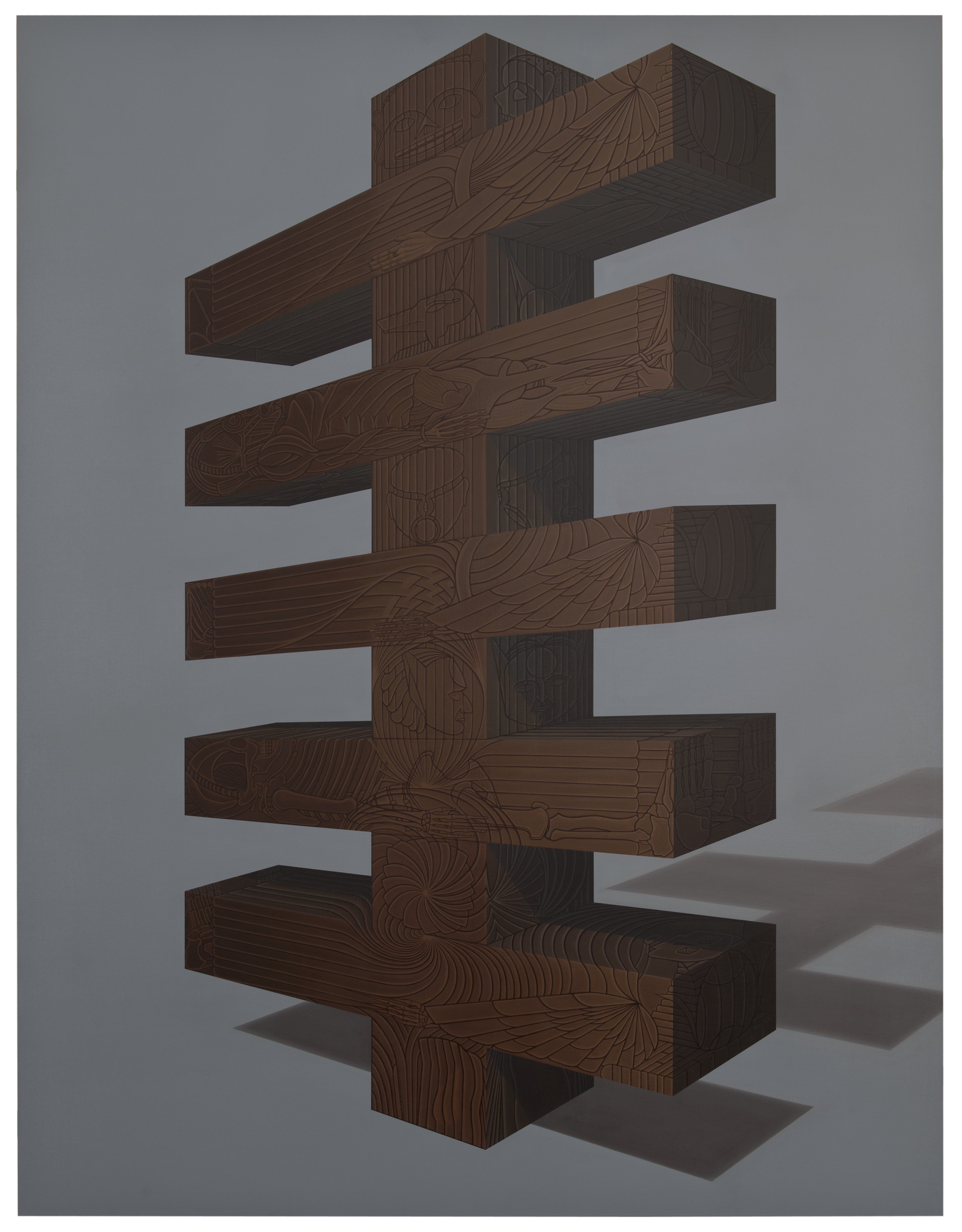

To explore the idea of perfectionism in relation to this series of exhibitions, the artists involved each create their own, very particular framework for undertaking research and practical making, and push themselves to explore every corner of it. The first Perfectionism exhibition in 2014 took a general look at this particular kind of artistic practice: meticulous dedication of time and a clear set of intentions. The resulting show was quiet and considered. Included was British painter Dale Adcock, a good example of the confluence of highly intellectual interrogation combined with meticulous and carefully considered practical application. Adcock’s work encompasses a dizzying array of references from ancient tribal and folkloric symbolism through to modern-day iconography. His paintings are monumental in scale and ambition, each one taking up to five years to complete due to their labour-intensive process, influenced by the classical masters. They are icons for today; totems of our past and our future, bringing together history, myth, scientific discovery, religious symbolism and popular culture. The hand of the artist is invisible and yet palpably present; these are works created by hours upon hours of human endeavour.

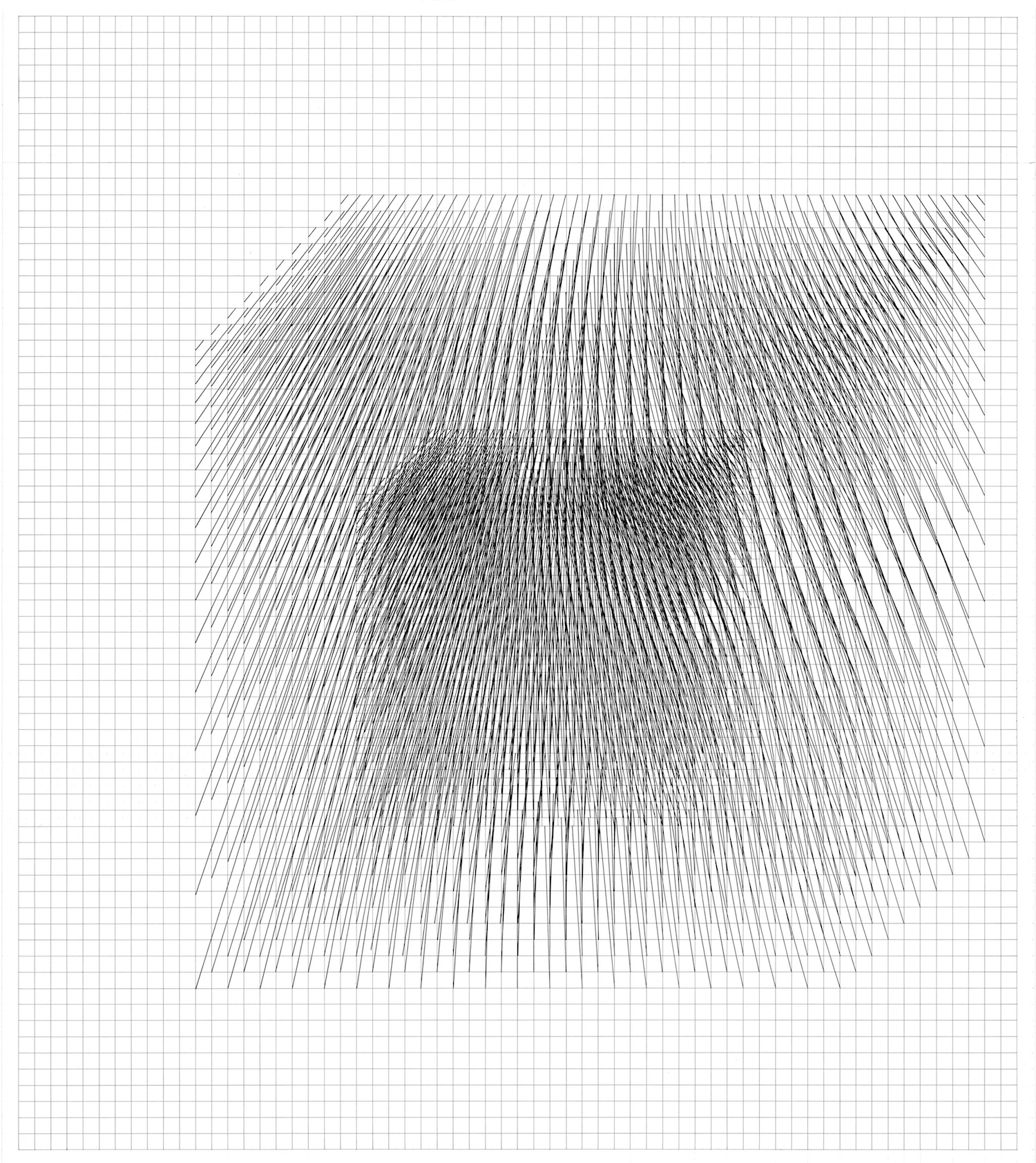

In Perfectionism (part ii) the following year, I became interested in the idea of repetition as a way of perfecting a process. Bringing together a group of artists whose practice involved a set of repeated actions or images—with an eye to Malcolm Gladwell’s claim that one could become an expert in a particular field after dedicating 10,000 hours to honing the skill required—the exhibition posed the question: does practice make perfect? Participant Wendy Smith, a much-underrated artist, is an explorer of the unknown; her delicate and meticulous geometric line drawings representing personal adventures into the liminal spaces of our existence. On first glance, they appear painstakingly planned and predetermined by a set of mathematical principles, but in reality they are created through a dynamic and intuitive process that requires absolute focus from Smith. She taps into something deep and ancient, and in so doing reveals to her viewing public a glimpse of the energetic forces driving the universe. This is only possible through complete knowledge of, and trust in, the materials she uses; most often black fine-liners on white paper, but the work also takes the form of elegant tonal gouache paintings.

The quest is for truth through materials; the results are not perfect but the process becomes ever more so with each undertaking.

The third part of the series, Perfectionism (part iii): The Alchemy of Making, turned towards the idea of transformation of materials, looking at a range of artists whose practice involved taking a material through a meticulous and carefully planned process in order to change its presence. Very much like a sixteenth-century alchemist, the “perfectionist” in this instance undertakes a combination of academic study and practical experimentation. The quest is for truth through materials; the results are not perfect but the process becomes ever more so with each undertaking. Exhibiting artist Nikolai Ishchuk always begins his process with a photograph; often broadly abstract, the photographic image is folded, painted over, scratched into and embedded into concrete so that it becomes something other. After withstanding several transformative processes, the resulting object is almost completely removed from its original state; it has taken on a new status. Ishchuk is an alchemist in the old-fashioned sense; he seeks truth through traditional methods, new experiments and pushing materials to their limits.

As I begin to think about the next iteration, due to take place in autumn 2018, I am starting to realize that this form of artistic perfectionism is not exclusively tied to manual labour and hand skills; it is a way of thinking about, of interrogating, of engaging with the world. My research for Perfectionism (part iv): Constructing Realities has so far encompassed the work and writings of artists such as Toby Ziegler, Hito Steyerl, Marguerite Humeau and Camille Henrot; artists who are working at the incredibly exciting confluence of academic research, technological advancement and artistic practice. They are concerned with imagery, with the ways in which humanity is communicating in ever-more visual forms, and they are also master craftsmen in their chosen fields. Their work is deeply researched and multilayered, pulling us into a swirling mass of information, uncertainty and a mix of fact and fiction that questions the very nature of imagery in today’s society.

“Many would say that artists are the early warning system for incoming threats to our society.”

Mass reproduction, digitization and the internet have exploded our world view over the past thirty years. So what is the role of the artist today, and how do they make their voices heard among the chaos of the information age? Many would say that artists are the early warning system for incoming threats to our society, their eyes and ears open to barely perceptible shifts in atmospheric pressure. While contemporary art doesn’t necessarily offer solutions to modern-day complexities, it is a place where the boundaries of convention are pushed at and new ideas are tested. The artistic practice discussed here takes into consideration both history and future, delves deep into the past and reaches far out into the as-yet-unknown; a practice that takes nothing for granted and makes no assumptions. Accelerationist theory posits that for humanity to not only survive but thrive on this planet, we must collectively undertake “a form of abductive experimentation that seeks the best means to act in a complex world”. ¹ Rather than technology chaining us further into the neo-liberal machine, it instead calls for the future to be “cracked open once again, unfastening our horizons towards the universal possibilities of the Outside” (Alex Williams and Nick Srnicek, #ACCELERATE: Manifesto for an Accelerationist Politics, 2013). As the world becomes ever more complex, technology advances and populations grow, perhaps the arena of contemporary art is where this experimentation is happening most progressively.

Becca Pelly-Fry is Director and Head Curator of Griffin Gallery in west London, and Head of Artist Engagement for Colart International, a global art materials manufacturer and parent company of Winsor & Newton, Liquitex, Lefranc Bourgeois and Conté à Paris.