When I got my first period nearly 20 years ago, like many tomboyish kids, I hated it. I hated that my body was suddenly doing things I didn’t want it to; I felt I was forced to reconcile with the idea of being a “woman”. Where a handful of girls at school proudly yelled about leaking, tampons and cramps, I couldn’t think of anything worse than admitting that my body had hurled itself into an arena that felt as much an emotional battleground as a physical one.

While it was difficult to articulate as a teenager, the whole experience felt political. I had spent years defiantly listening to Blur, not the Spice Girls; laughing at the ludicrousness of sticky Juicy Tubes lipgloss or the idea of wearing anything but enormous t-shirts and Dr Martens boots. Girliness felt so pointless and daft. Periods and the pinky-purple floral patterns of sanitary products were the ultimate symbols of a very gendered world that I had no interest in being a part of.

If conversations around menstruation had been as open, frank and shame-free as they are (slowly) becoming today, perhaps things would have felt different. It seems as though many people, though I can’t speak for teenagers, are moving away from tampon-up-the-sleeve secrecy. The design and advertising teams that want to sell such things need to help accelerate those changes.

There’s a long way to go, and while these brands ultimately want to sell things, for them to do so they should look to catalyse a shift away from menstruation as taboo. Schools still do little in the way of educating young people about periods; the psychological side is rarely touched upon, and aside from family guidance, many girls have little to go on, aside from branded campaigns, when it comes to understanding what “Aunt Flo” is really like. Brands and the creatives they work with have a big responsibility.

Back in the 1980s, discretion was a prime selling point for tampons (though not outfits worn in the commercials, if this neon-laden Playtex spot

is anything to go by). This notion was further perpetuated by those early 2000s Tampax Compak ads, which pushed the idea that the product was so good, people would likely mistake it for a sweetie. Periods were nothing more than embarrassing monthly encumbrances, and firmly just for “the girls” to worry about.

A recent baffling talkshow-style Tampax ad moved away from discretion, but took a sort of Carry On Menstruating approach, and was pulled following numerous complaints to the ASA for phrases like “You gotta get ’em up there girls” which complainants described as “offensive” and “crude”. It’s just another little footnote in society’s ongoing failure to see periods as anything more than bleeding, rather than a perpetual, cyclical, holistic health topic.

“Packaging designs still lean toward infantile distraction techniques, like butterflies, floral patterns and saccharine pink”

In creative industries where men overwhelmingly dominate top positions (IPA research suggests that 89 percent of creative directors in the UK are men), perhaps it’s little wonder progress has been so slow and packaging designs still lean toward infantile distraction techniques, like butterflies, floral patterns and saccharine pink. Yet better design work is emerging. Numerous recent rebrands and product launches have promised they’re moving on from “periods equals embarrassing” and towards a more “lifestyle” approach, in line with wider cultural trends, such as sustainability and openness.

Sales of Mooncups, for instance, have risen by 98 percent over the past five years. The company’s rebrand by Bluemarlin eschews photographs of flowers and takes a Scandi-like, more minimal design approach “that people could ultimately feel proud of”. Emerging “eco period care” brand TOTM has eye-catching colours and patterns; like any other product sold in supermarkets, it wants to jump off the shelf.

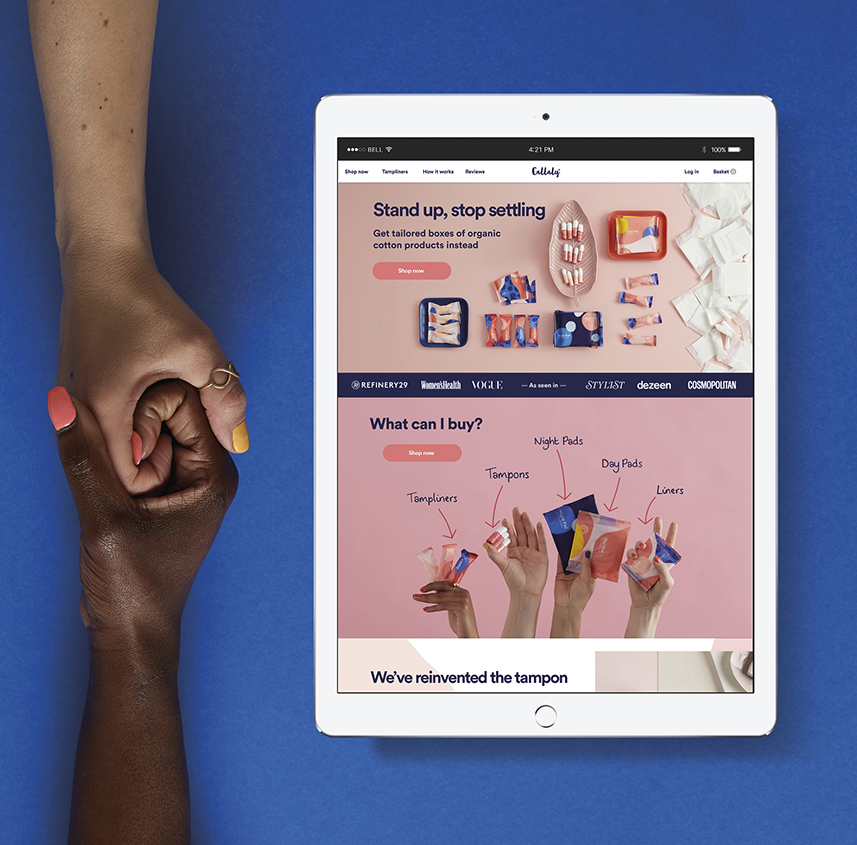

- Callaly website designs by Design Bridge

Yet even many of the newer brands, which have innovative models such as personalised subscription services, move towards discretion. While many claim their bold designs and upfront copywriting do away with shame, they still disguise what the product actually is in some way. Teen-focused brand Betty works with the agency

Straight Forward Design, which proudly states that “because they don’t follow the stereotypical trend of period products, if a pad or a tampon fell out of their bag at school… onlookers won’t be sure what it is”. While this may ultimately be appealing to many, it still feeds into the notion that periods are something to be ashamed of.

Design Bridge’s work for organic tampon subscription brand Callay looked to move away from “girly clichés” and make its products “something that anybody could be proud of” using “informative, confident, conversational” copy, popping colours and a striking graphical look. The agency says it wants to take Callaly out of the “cabinet of shame”.

More positive changes are being made with Bodyform. The brand’s recent campaign continues its moves towards more honest, holistic discussions of periods: its 2017 #BloodNormal campaign was the first TV ad to use red, rather than that once-familiar blue, liquid. Last year, its Viva la Vulva ad acted as a glorious celebration of physical differences, featuring art by an all-women animation team including Anna Ginsburg

. The spot features a singing clitoris, a healthy dose of camel toe, and a tonne of vulva proxies including oysters, cupcakes, gemstones and origami.

Bodyform’s latest campaign, Womb Stories, by agency Abbott Mead Vickers BBDO, launched in July 2020. It chronicles the multifarious ways periods affect women through animations, again created by an all-female team. The motivation (as well as selling Bodyform products, obviously) was to highlight the complex, less discussed experiences of people with wombs, which are often shrouded in shame, and to encourage more openness around them. The advert touches on subjects like nipple hair, getting your first period at school, miscarriage (the much less discussed reason people use sanitary products), menopause and infertility.

“The ad features a singing clitoris, a healthy dose of camel toe, and a tonne of vulva proxies including oysters, cupcakes, gemstones and origami”

Historically, adverts have promoted the idea of periods as little more than clockwork monthly secretions, which are easily solved by buying things to absorb them. At their worst, they could cause little gusset stains, bring on cake cravings and make you a bit grumpy. Creatives need to look towards approaches like Womb Stories, and acknowledge the complexities of periods as emotional, psychological and even societal.

Bodyform’s campaign was smart in opening up these conversations, and was also shrewd in appealing to women who had likely long felt silenced. Womb Stories’ launch was accompanied by research which found that 68 percent of women with experience of miscarriage, endometriosis, fertility issues and menopause said that being open with family and friends helped them cope. By selling on openness, they’re making these women feel heard, especially in light of another of the study’s findings which showed that 21 percent of women reported feeling that society actively wants them to keep silent. Sure, it’s marketing, but if people feel more able to talk about such problems, the benefits are enormous. This is a major health issue: 44 percent of women who reported feeling unable to discuss these problems say their silence has damaged their mental health.

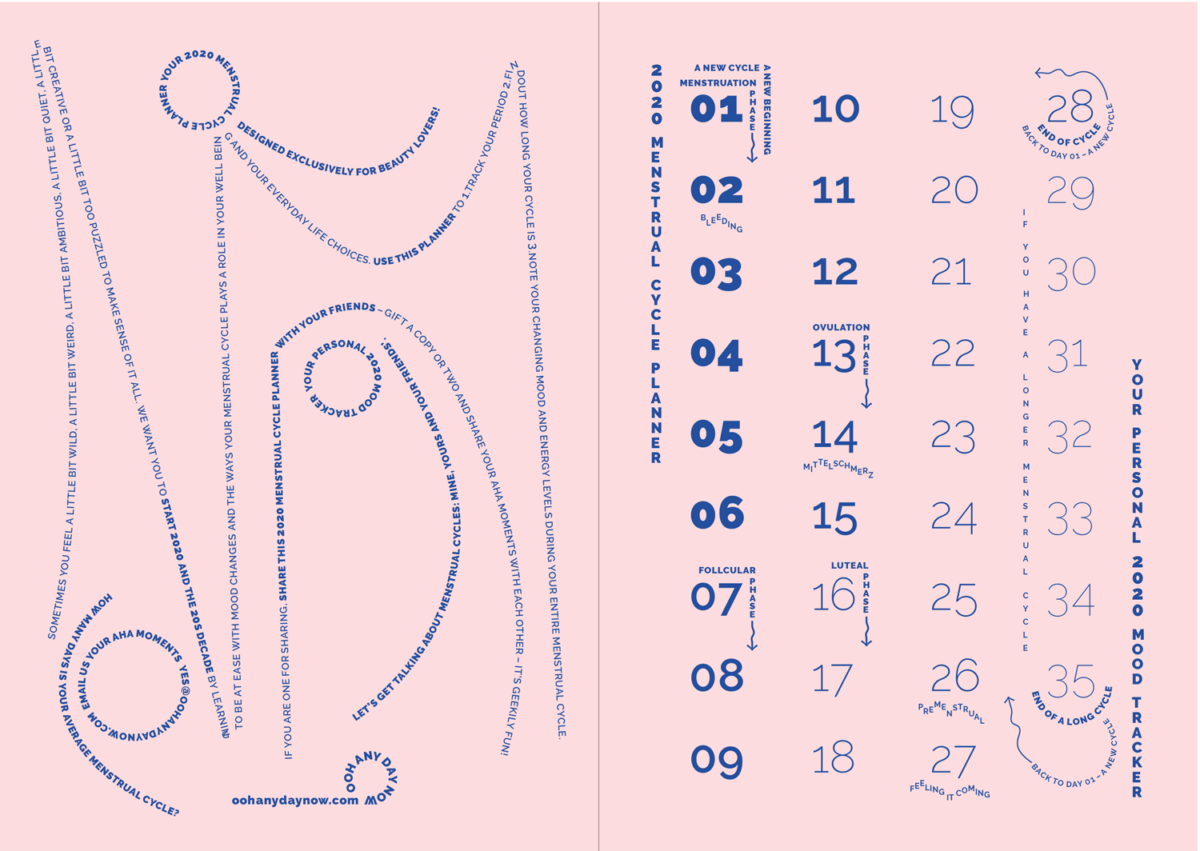

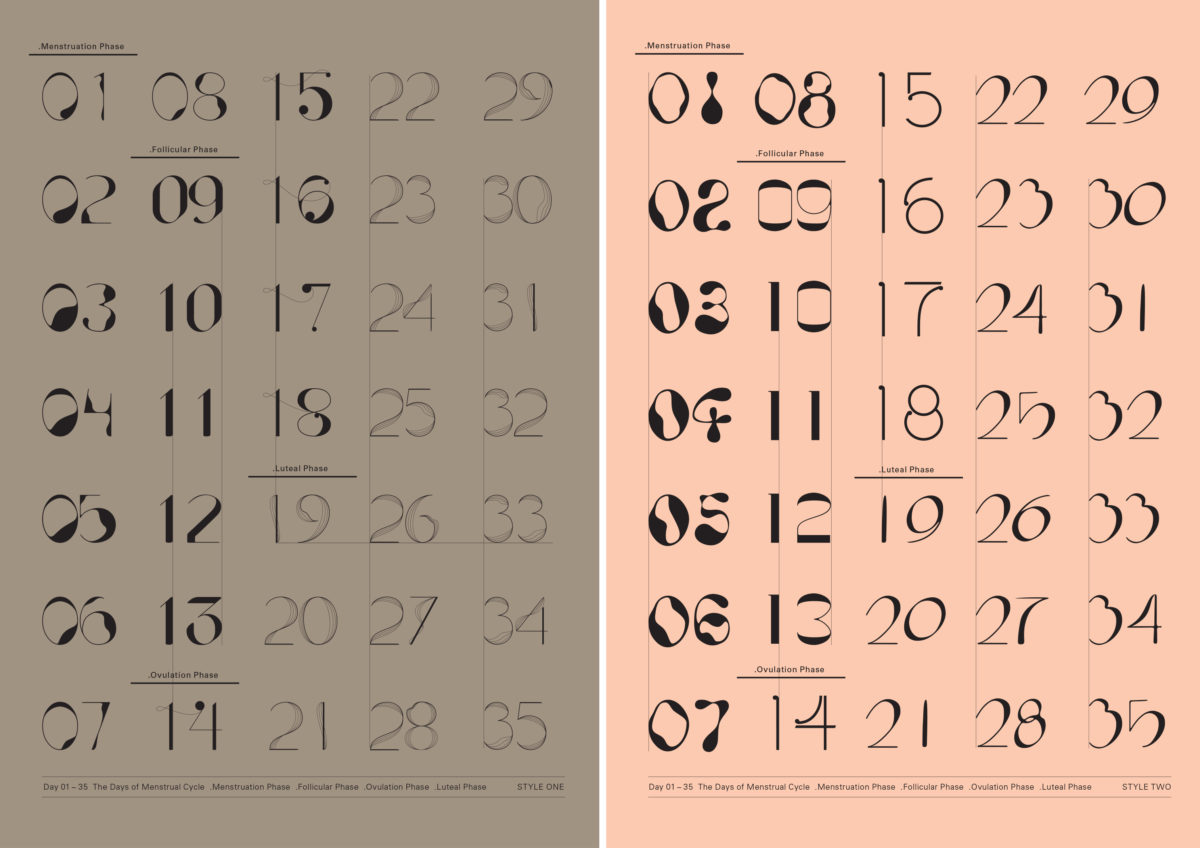

Hopefully, younger generations will take openness around menstruation as a given. Organisations like Ooh Any Day Now (OADN) hint that things are changing for the better. The design platform’s website sits in the trendy graphic design school camp: accents of muted terminal green, wry typographic in-jokes nodding to various fashion houses, a kind of effortlessly hip youthfulness bridging sass and chill. Reframing periods as “acts of resilience and strength”, the platform does a fantastic job of normalising them, as well as pushing the fact that blood is just the visible, viscous physical signifier in a five-part, cyclical process that’s woefully overlooked.

Such initiatives are small but significant steps. Being able to finally discuss periods has been life-changing for me: during and since the ten years when my periods almost totally stopped, I’d been led to believe by both male and female doctors that it was all my fault: my lifestyle, weight, habits. I’d been bad, so I was denied this central tenet of “womanhood” and might be punished by crumbling bones. A five-minute chat with my mum revealed she’d gone through exactly the same thing when she came off the pill, and was told to go away and eat a Mars bar. That knowledge, coupled with wider discussions around things like Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD)—finally acknowledged by the WHO just last year—is a profound form of emancipation that takes minutes to discuss, and impacts people for an entire lifetime. Knowledge, as the cliché goes, is power.

- Ooh Any Day Now menstrual cycle calendar

“Women have long internalised the idea that they should feel and act the same throughout the month”

OADN’s platform hosts period-centric texts and visual essays, and a design-led boutique. This approach orients periods as just one part of a very twenty-first-century, youthful, fashion-led, quietly feminist lifestyle (think high-end Depop meets “new ugly” graphic design). Typographically-led planners are a standout—simple but not too minimal, cute but not too twee—aligning the physical aspects of periods with their emotional counterparts and refreshingly showing that the 28-day-cycle, often held up as a menstrual gold standard, is not a reality for most people.

The Bloody Yes calendar is a similarly design-led tracker from Swedish collective Shevolution. Slightly less hipsterish aesthetically, yet clearly created with an artsy-leaning audience in mind, the calendar features 12 different women illustrators alongside insights from scientists, fertility experts and “body activists” like artist and M.I.A drummer Madame Gandhi.

The calendar positions period knowledge as a key tool for female empowerment: “Unfortunately, society wasn’t designed to accommodate a cycle that differs from a man’s,” says Shevolution. “Instead, women have long internalised the idea that we should feel and act the same throughout the month, whether it comes to productivity, social life or libido… By learning about our cycles, we get access to an extraordinarily powerful catalyst for productivity and well-being.”

The project spotlights the depressing fact that so few women, even in privileged, highly educated, relatively liberal parts of the world, really understand menstrual cycles. If that seems like a sweeping statement, consider how few people in your social circle realise that it’s pretty much impossible to get pregnant outside of a three-to five day window each month. I learned this in my early thirties, and I’d say the majority of my friends across all genders still haven’t.

Knowing more about periods and women’s bodies doesn’t just impact those who experience and live in them, but already-overstretched health services around the world, family relationships, the kind of sex people have, how people work and where, and society as a whole. It’s not just about wombs, it’s about agency, and the more creative teams that perpetuate this, the better.