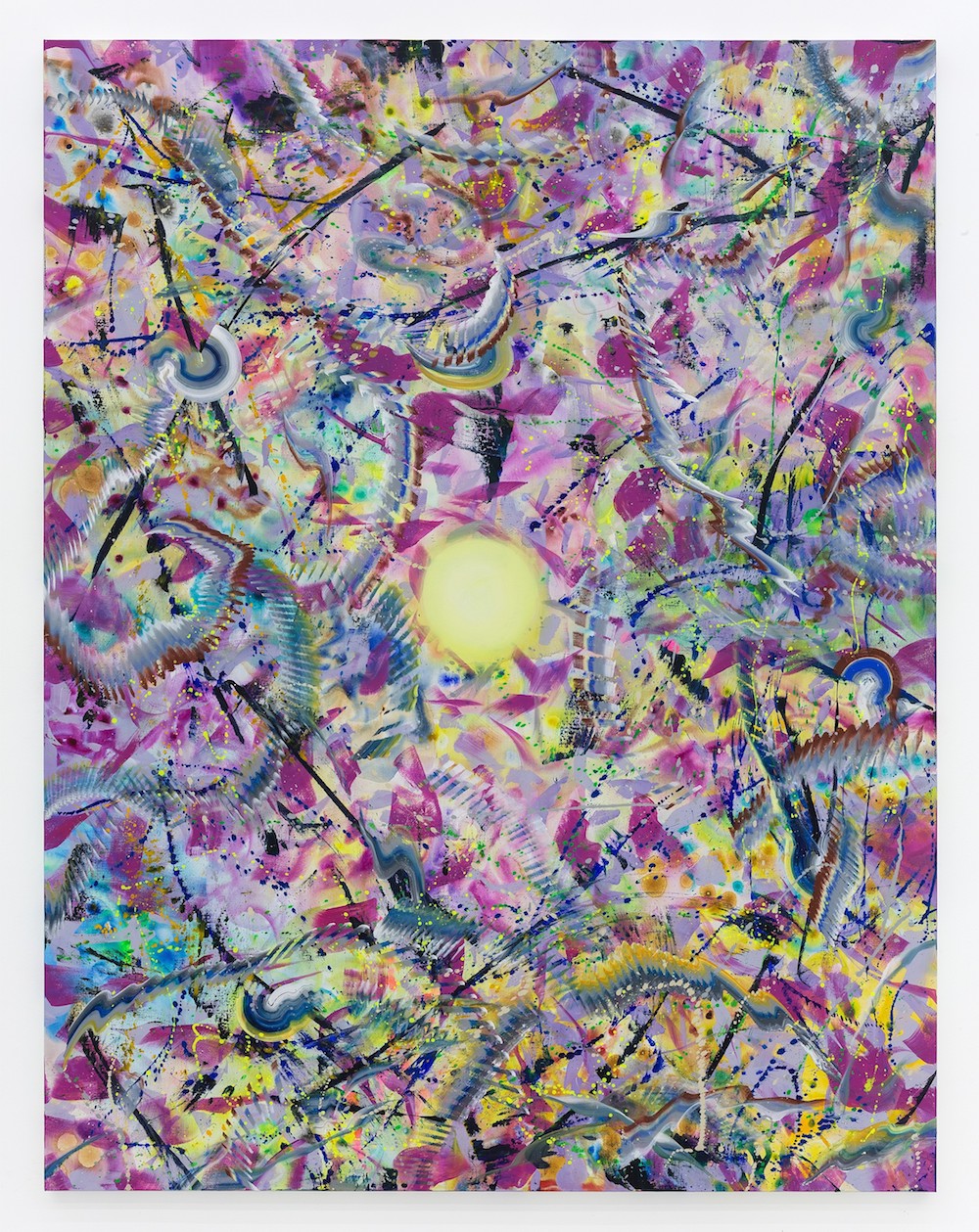

Sometimes illness can be fertile ground for artists. The painting Out of Reach No.2 (2017) by Beijing-based artist Wang Haiyang is part of a series which emerged during a period of convalescence that lasted over half a year. On display at White Space Gallery at this year’s Art Basel Hong Kong, the large-scale painting is an explosion of shapes and swirls in psychedelic pink, blue and yellow hues, except for a blank circle at the centre of the canvas that draws our focus amidst the colourful chaos. As his illness prevented the artist from standing for long periods of time, Wang Haiyang stretched the canvas over four chairs and painted around it, gradually making his way from the edges towards the middle. However, his arms could not reach the middle of the canvas, so he decided to leave a blank space as if to mark his ailing body’s limitations. Currently the subject of a trippy solo exhibition at White Space Beijing, Wang Haiyang’s work plunges us into the artist’s inner world, channelling his subconscious and inviting the viewer to partake in its very own logic.

Many of the standout presentations at this year’s Art Basel Hong Kong, which opens its sixth edition today, mine personal experience and biography, creating works that feel distinctly intimate, reflective or pull us into the artist’s private sphere. Alexie Glass-Kantor, who curates the fair’s Encounters section—a programme of site-specific installations and large-scale sculptures situated along the fair’s main thoroughfares—notes that this year the gallery submissions were less immediately focussed on the more universal problems of our times, but rather marked a renewed interest in the personal sphere. “Last year my presentation was very directly political, but this year, post-Brexit, post-Trump, post the sociopolitical turbulences in the Asia-Pacific region, the gallery proposals seemed to show a greater connection to the intimate, to the familiar, to what’s at hand and to the material.”

Erwin Wurm at Lehmann Maupin, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, König Galerie © Art Basel

The Encounters programme is characterized by works that demand the audience’s direct involvement, to varying degrees, from mere touch to full-on participation. The most obvious example is Erwin Wurm’s subversive One Minute Sculptures (2000-2018). Modest everyday objects, ranging from furniture, discarded toys and items of clothing, are scattered across a large white platform. Each piece comes with written or illustrated instructions detailing how to “activate” it, invariably playful and idiosyncratic. Wurm’s clever and humourous work requires that the participant put him or herself in the vulnerable position of the artist under the viewer’s scrutiny, inverting traditional roles of maker and spectator.

One of the most eye-catching booths at this year’s fair is undoubtedly Long March Space’s solo presentation of Yu Hong, one of China’s foremost artists who, like many of the country’s finest painters, trained at Beijing’s venerable Central Academy of Fine Arts (CAFA), where she now teaches. Her painting prowess is on ample display in the booth, which is dominated by a colossal, nine-metre long canvas that occupies the full length of one of the walls. Aptly titled A New Century, the painting depicts a post-apocalyptic scene populated by a forlorn cast of characters (including two children wrapped in reflective emergency blankets), who balance precariously on a thin branch, as a city’s skyline goes up in flames beneath them. The painting clearly alludes to the many ills that Yu Hong sees in our modern society, and is exhibited alongside a series of smaller-scale works that are less allegorical and often capture a particular moment of intimacy or tenderness.

Perhaps the most entrancing of Yu Hong’s works on display, however, shows her equally at ease in digital media as she is in painting. Entitled She’s Already Gone, the four-part virtual reality experience which premiered at the Farschou Foundation in Beijing earlier this year, charts the life of a woman from the moment of birth until old age, composed of a series of frames hand-painted by the artist and adapted for virtual reality. Yu Hong, who was born in the early years of China’s Cultural Revolution in 1966, draws widely from her own biography and experiences in the work. It shares the intimacy and candidness of her oil paintings but adds a whole new narrative and temporal dimension. For an artist like Yu Hong, with such an ability to tell human stories and draw you into their inner world, this is but a glimpse of the possibilities of the medium.