Ali Mobasser’s work grapples with the nuanced nature of his identity. The London-based photographer narrates the stories of his family members, who as part of the Iranian diaspora led complicated lives of their own. In assuming the role of storyteller, he creates a form of catharsis for himself, charting the history of his own family.

In 1979, when he was three years old, Mobasser’s family fled Iran following the revolution. After a period of moving from one country to the next, they sought refuge in the US, and his parents separated; he remained with his mother while his father moved to the UK. In 1985, Mobasser was put on a plane to London to visit his father for the summer, and as September drew near, he was told that he would not be returning to his mother. His aunt, Afsaneh, stepped in as a maternal influence. Thus began the next period of his life, as he tried to find his feet in Putney, London. After turning 18, he went to study at Kingston School of Art. “I always went back to photography; it has the power to create narrative,” he says. “The art I like is that which tells someone’s personal story. Politically, everyone’s trying to find the next cause and to go help others, but I think you need to look at yourself first, before trying to save the world.”

“I always went back to photography; it has the power to create narrative”

Politics had ruled Mobasser’s family life for so long that he wanted to be rid of it. In order to find his voice as an artist, he worked as a photographic assistant in the fashion industry for five years, before taking up a role as picture editor at the BBC. “I do try to keep my work apolitical. My grandfather was part of the pre-revolution government, and my father was part of the anti-regime movement. I used to use my physical addictions to escape; since giving up drinking, my work is my only addiction. My therapy has been trying to figure out more about their history.”

- Ali Mobasser, Afsaneh Box 3

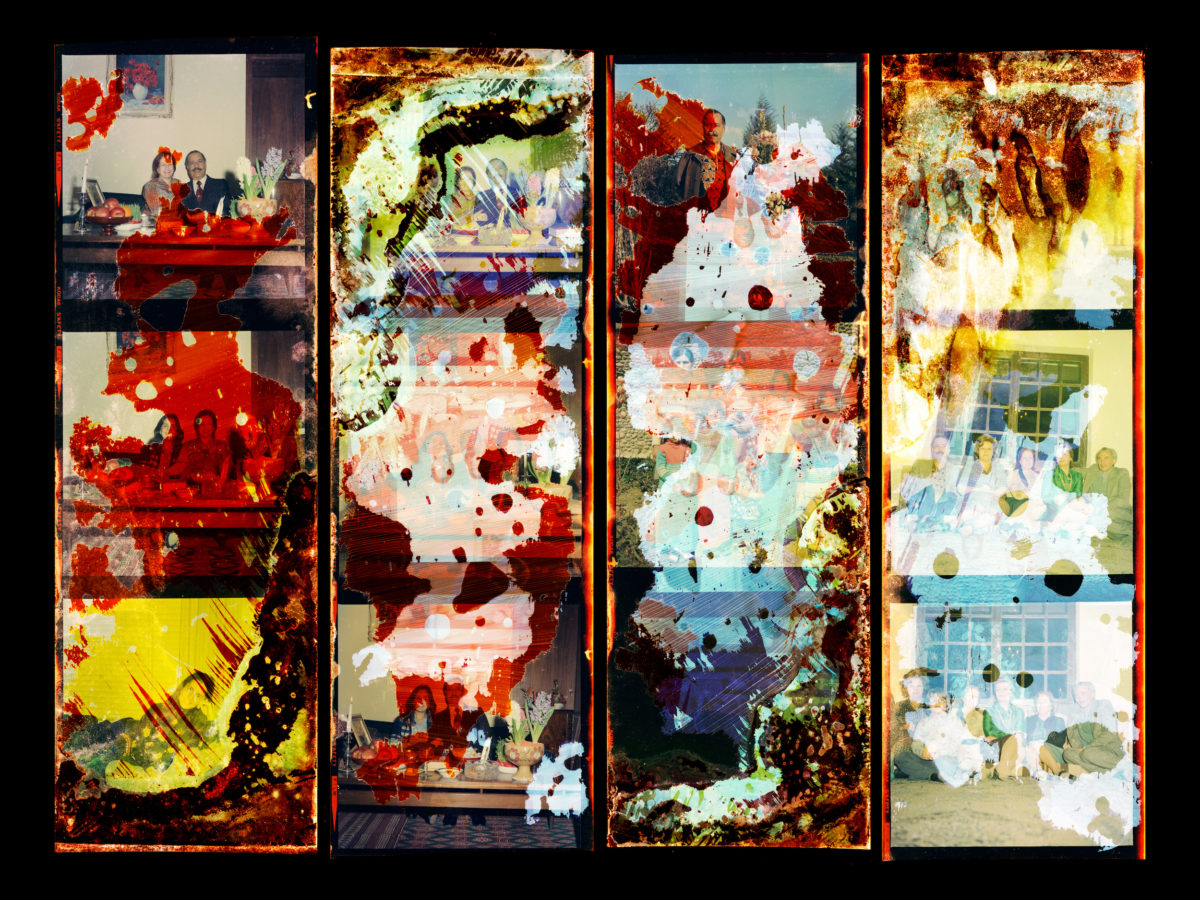

When Mobasser’s father passed away, and he found a box of his grandfather’s medium format negatives nestled underneath his bed, the photographs helped him through his grieving process. Death enabled Mobasser to unearth stories about his family, in a way that wouldn’t have happened if they were alive. “It was so traumatic hearing the older generation talk of these times that we never spoke about it,” he says. The negatives formed The Pieces of My Grandfather’s Broken Heart, a project which was exhibited at Arles in 2018. Water damage resulted in beautiful distortions on some of the contact sheets; a medley of colours corrupt the imagery, almost as if nostalgia were bubbling up from the pictures themselves. For Mobasser, they reflect his determination to find beauty in the trauma of his family’s story.

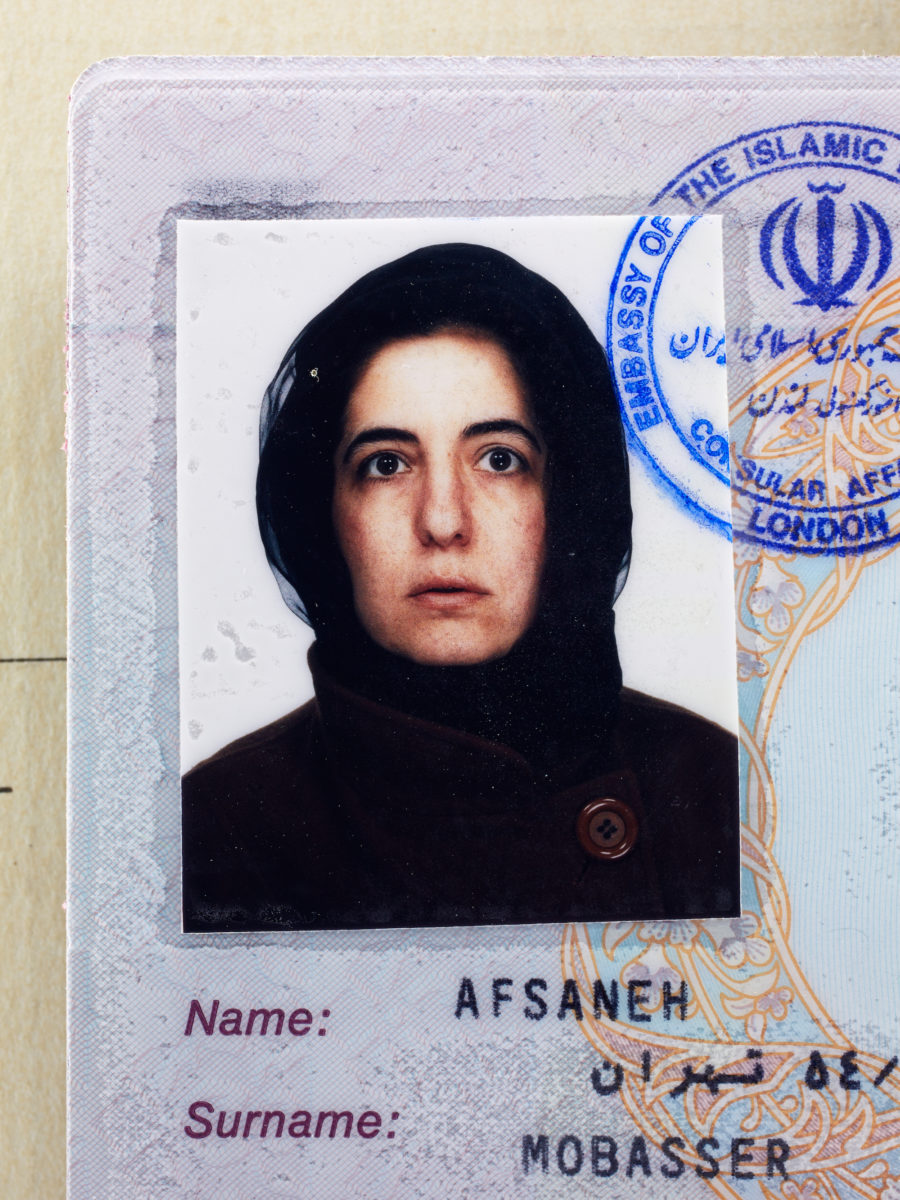

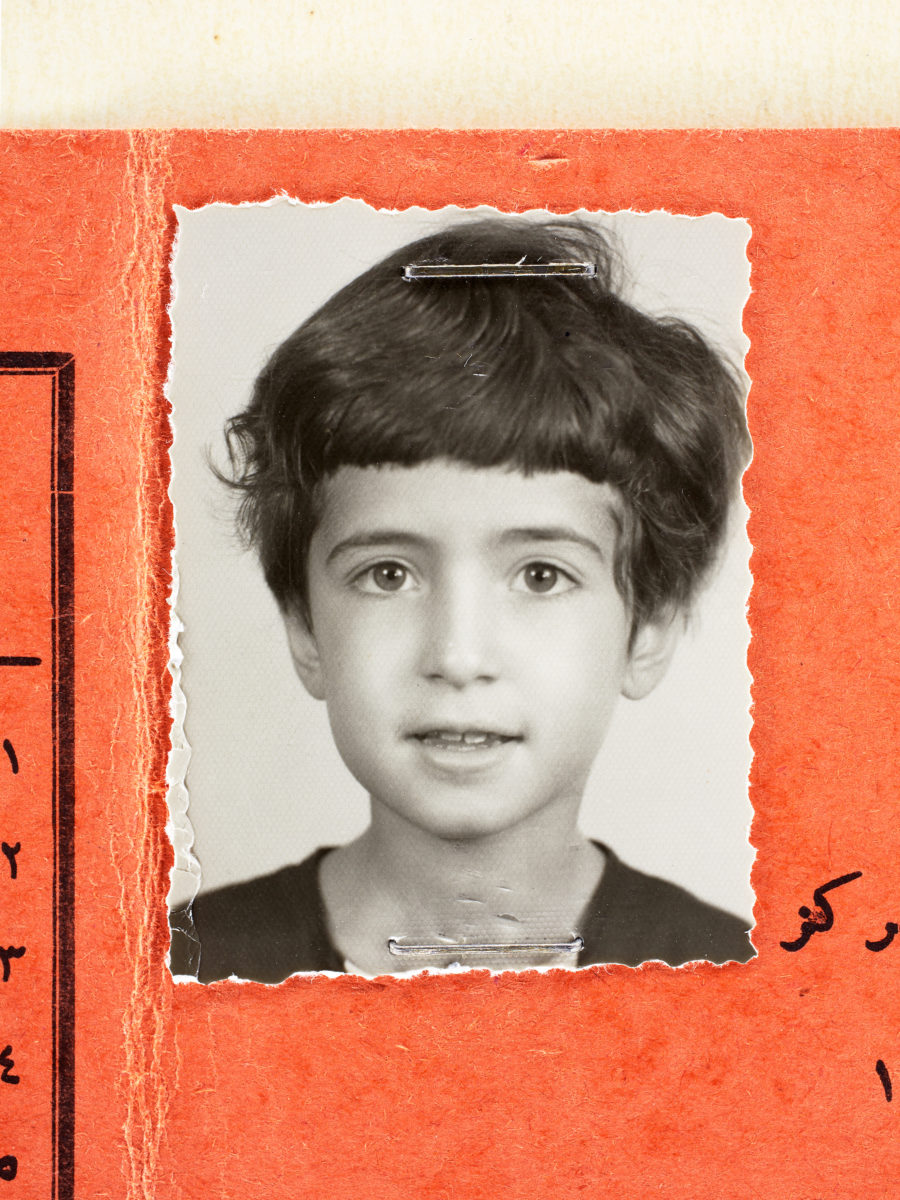

The artist’s Afsaneh Box series helped Mobasser process his aunt’s untimely passing. Box 1 showcases images of Afsaneh’s house on the morning of her death, while Box 2 depicts her possessions with startling focus. He spotlights each object with a loving dedication, using the camera to imbue her belongings with importance. “I treated my aunt like an art director, a posthumous force shaping the outcome.” It’s Box 3, however, that tells Afsaneh’s story with the most poignancy. Sorting through her belongings, Mobasser discovered his aunt’s report cards and identity cards from different stages of her life, visualising her passage from childhood into adult years.

- Ali Mobasser, Afsaneh Box 3

“A medley of colours corrupt the imagery, almost as if nostalgia were bubbling up from the pictures themselves”

There’s an ephemeral nature to the photographs. The viewer is privy to acute levels of intimacy in seeing the subject up close in a series of portraits which also showcase the changing nature of photography. The Iranian revolution is symbolised by the harshness of the photobooth in comparison to the nostalgic portrait set-up of earlier years, and Afsaneh’s time as a refugee is chronicled by a particular travel document that moves from monochrome to colour photography. In reversing the chronology of Afsaneh’s story, moving from her most recent Oyster Card picture to her youth, Mobasser explains that he avoids “a sad ending” for the series.

The projects are a kind of visual journalism, an archive of tales that could have easily been lost in the momentum of migration, and Mobasser acts as a curator as much as an image-maker. He explains that he takes issue with the fact that photography is heralded as the most truthful medium: “The photograph is very opinionated, or it lies. Society’s biggest flaw is believing the image.” The artist is under no illusions that his projects offer any kind of universal truth, but rather, an untold side of history. “It’s not your typical refugee story. We were privileged kids who lost everything, and people don’t want to talk about it because it’s not the usual narrative.” Through excavating stories from his heritage, he puts the personal on a pedestal, offering audiences a window into an oft-forgotten world.