I’m struggling to work out exactly where Saelia Aparicio is from—all I can find online is a “secret Spanish island”—and the difficult is partly down to our mutual terrible phone signal—despite the fact that we’re just a few miles up the road from one another in less-than-glamourous parts of East London; partly due to her beautifully thick accent and rapid-fire approach to talking; and partly down to the answer itself, once she offers one. Where is she from? “A mental space”.

Aparicio lives in Peckham, having moved to London to study sculpture at the Royal College of Art from somewhere that may or may not be a Spanish island. In a way, she’s from “no place”—the Greek definition of Utopia—yet her artistic impulses draw mainly on things that could be considered dystopian—such as mould, climate change and so on. She, and her work, are full of dualities: everywhere and nowhere, utopian and dystopian, funny as hell but serious too.

The Carpenter’s Estate, where her studio is based in Stratford, has been the subject of much of her work in recent years, which spans film, animation, drawing and installations taking in everything from sculpture to found objects to the use of scent. Her short film based on the estate was recently shown as part of a programme organised by the Serpentine called The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish with Plants.

“She, and her work, are full of dualities: everywhere and nowhere, utopian and dystopian, funny as hell but serious as hell too”

She’s preoccupied with space; both the literal spaces she lives and works in, and the way that space can be used as a medium in her installations. These are often site-specific and labyrinthine, jerking the viewer from one peculiar assemblage to another to raise and ask questions about societal inequality, sustainability and the strange way we separate two apparently apposing tropes of our bodies—sexuality and disgust.

Why have you found working in and with the Carpenter’s Estate so important to your work?

For a while I’d been wanting to change how I worked, for instance I stopped working with commercial galleries. There’s this whole thing that being a “good” artist means that you’re commercially successful, but I don’t think they’re related. I want to take a step back from that. Working more in the Carpenter’s Estate makes sense for my practice at the moment and what I see as being a “good” artist—things like collaboration, working with the things that are closest to me, and being democratic—the residents have become like a family to me.

I want to expand the Serpentine piece into a trilogy and make other things around it to create a whole atmosphere: a project of many projects. I think I fit outside of categories, so to me a house plant or a weed could be used to establish a tonality between a neighbour from the estate and a neighbour from one of the new build blocks around it. My work is often around things like sustainability and equality, the fact affordable housing is decreasing and inequality is rising, even in the UK. I find that very worrying. My work is making a comment on, or establishing a language through which to look at, these problems.

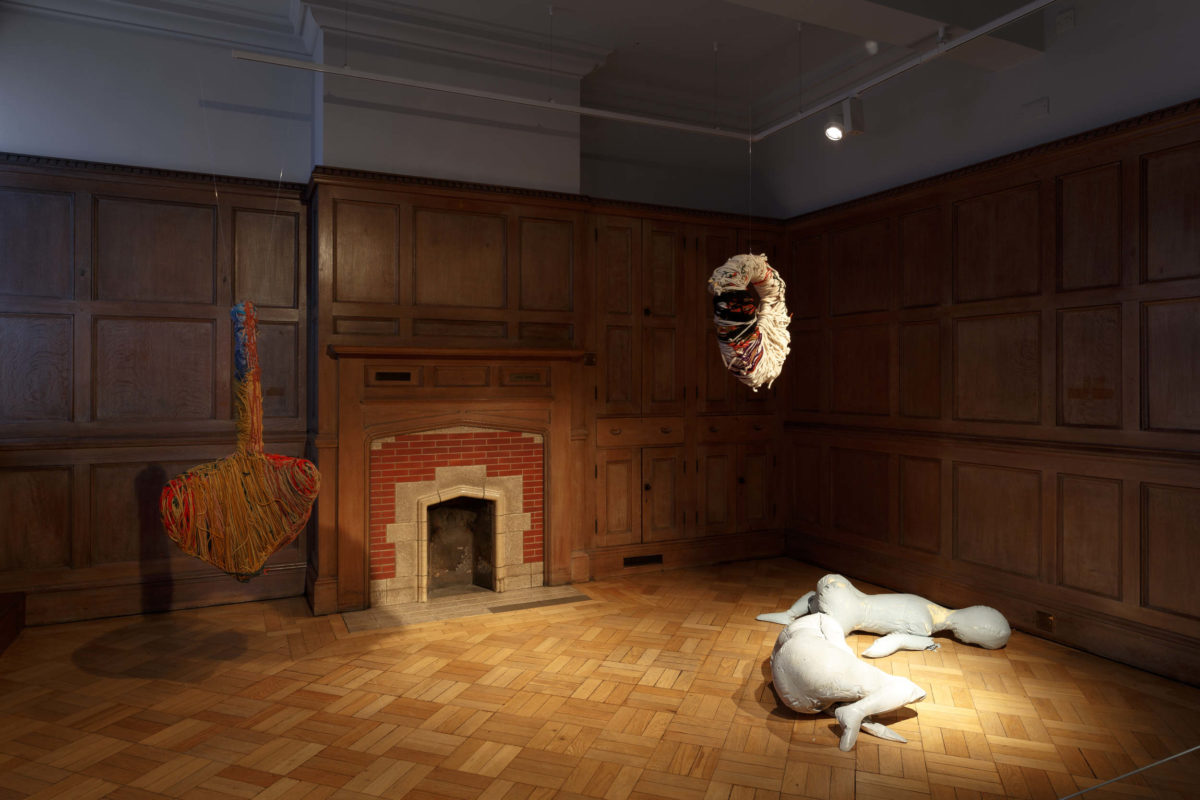

- Your Consequences Have Actions, 2017

“My work is making a comment on, or establishing a language through which to look at the problems that are there and which worry me”

That idea of space as a medium and a starting point seems to be important in the way you configure your installations too. How do you relate to space in your work more broadly?

It sounds like an oxymoron, but I want to create a sort of “mini-mart baroque” feel. It’s abut making an atmosphere within a new environment: a show I did in Madrid in January [Prosthetics for Invertebrates] felt like a mixture between a spaceship and a crazy lab. That idea of atmosphere is why I’m using smell more: often chemical smells give us a feeling of safety, but they’re harmful for our system, and I’m interested in the idea that things we trust are poisonous—they aren’t good for us or the environment.

In your piece Your Consequences Have Actions, the gallery discusses the idea of the body as a source of “wonder and horror”. Can you tell me more about what that means?

I don’t see the body as a source of horror but we’re living in a world that’s increasingly superficial and very related to the surface of the body. Things like fermentation and digestion are seen as gross and scary, but we all have this whole unknown world inside us that we don’t know and understand—I find that fascinating.

“Things like fermentation and digestion are seen as gross and scary, but we all have this whole unknown world inside us that we don’t understand”

There’s also always a sort of undercurrent of humour in your work. How does that play a role in your practice?

With the humour, I want to make art approachable to everyone: not just trained artists or people in that world who appreciate art. It has to work on different levels, and humour is a way of doing that. There are often different layers of humour in the same work: some are lighthearted, others are dark.

In my drawings, it’s not really deliberate; sometimes, when I draw men, they go more into the feminine spectrum. Why do I do that? Because I’m a feminist maybe… I just want to concentrate more on the feminine side of it; I want to put the spotlight on that.

The piece Prosthetics for Invertebrates looks really interesting. What was the thinking behind it?

It’s partly about how our obsession with cleaning affects us in a negative way: it’s harmful to our organisms and our environment. I was also thinking about cleaners, and seeing them in the work as a mix between cleaners and sex workers, like kinky cleaners. I worked a lot with cleaners and cleaning products and found objects.

It’s interesting when you think, for instance, about products like rubber gloves and latex gloves: the materials are often the same, but the meaning is very different [cleaning tool and sexy]. That’s very interesting. I was also noticing that some cleaning objects–especially in the way they’re marketed to women—look a bit like masturbators.

- Prosthetics for Invertebrates, 2019