A bloody and violent dream prompts the protagonist of Han Kang’s novel The Vegetarian, Yeong-hye, to give up meat. Haunted by this vision, she progressively withdraws from society and behaves in increasingly strange ways. She stops wearing a bra. She basks nude in the sun. She stops eating altogether, and stands motionless in the forest, trying to cast off her human body and become a plant.

I’ve been thinking lately about Kang’s novel in relation to the work of plant-obsessed, Philadelphia-based photographer Roxana Azar. In The Vegetarian, Yeong-hye’s refusal of her human body can be interpreted as an extreme protest against the patriarchal society she inhabits, and a way of expressing her own personal desires. Following Azar on social media, amid her posts exalting her houseplants, I’ve observed that her distaste for the patriarchy is palpable and often humorously expressed, particularly since the election. On the other hand, the luxuriant calm of Azar’s drop-dead-gorgeous, digitally manipulated photographs of dramatically lit plants and landscapes belies their critical nature.

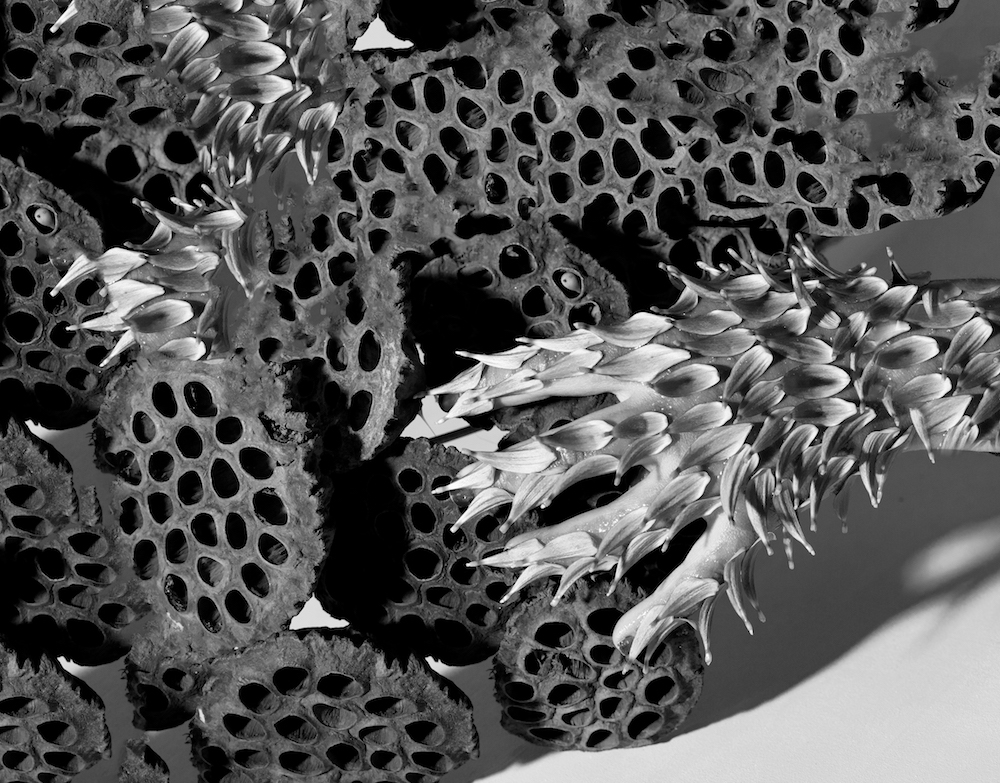

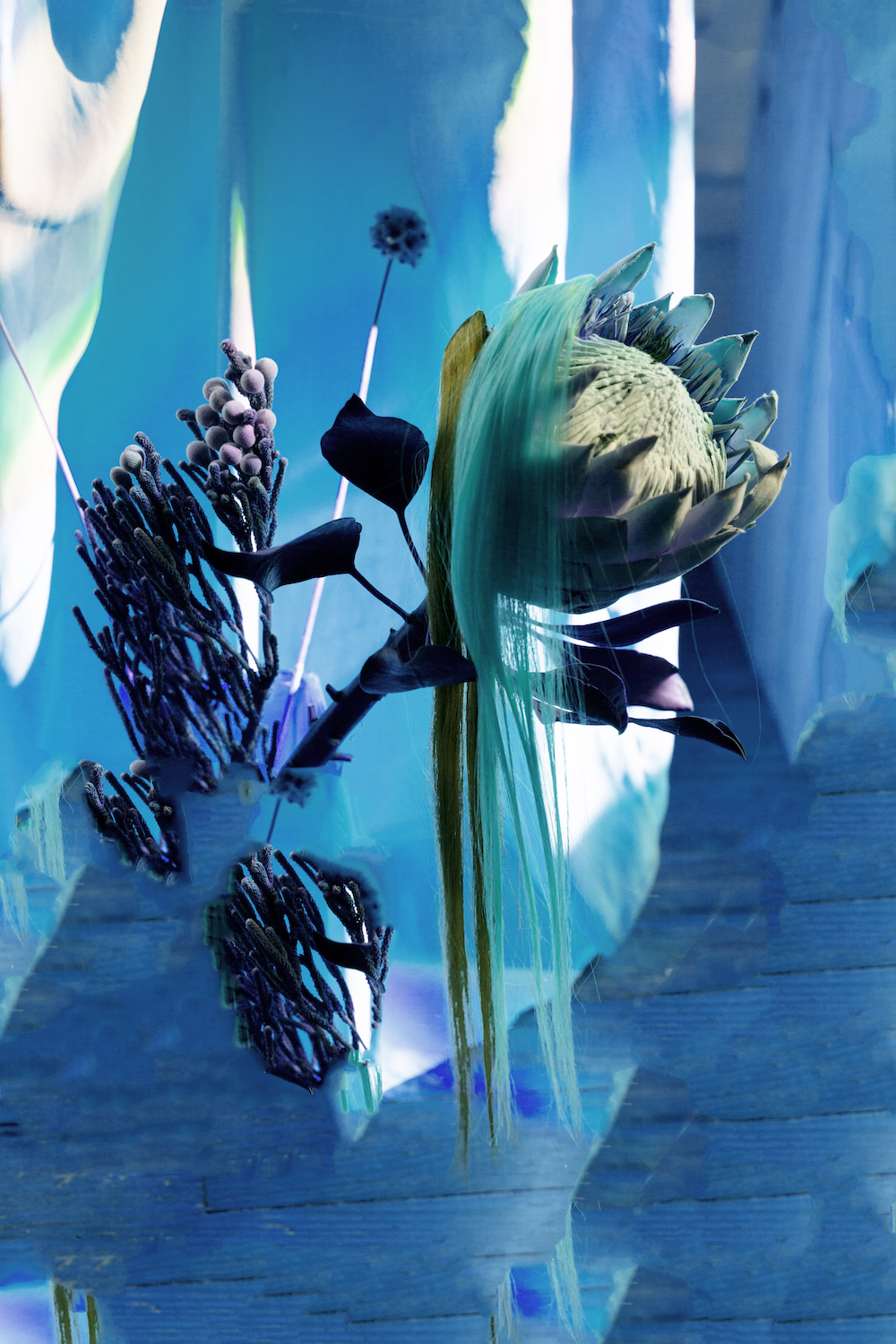

Like Yeong-hye, in her latest series, Roxana Azar, too, becomes a plant—or a Plantoid, rather. In her studio process, she switches between constructing sculptures and photographs, in the company of other exciting peers and predecessors in the field of photography, like Barbara Kasten, Erin O’Keeffe, Anastasia Samoylova, to name just a few. Science fiction stories that Azar writes serve as prompts for her image-making: her series Plantoid, part of Azar’s MFA thesis work from Virginia Commonwealth University, imagines what intelligent plant life would look like on another planet. It is a cross between the sentient atmosphere of Tarkovsky’s Solaris and CIA-man Cleve Backster’s telepathic communications with his dracaena (the same kind of spiky shrub subjected to language lessons by John Baldessari just a few years later), all under the cool blue hue of a sunset as seen on Mars.

For a generation staring down the barrel of a fucked future filled with fossil-fueled climate disasters, projecting an idealized version of the world onto the distant vistas of another planet contains an implicit critique of the current state of affairs, and how we got to this point. ‘I wanted to imagine a world where the landscape and plant life could stop their destruction at the hands of violent and colonialist human civilizations,’ Azar says. ‘I think the landscape is Othered a lot and is also gendered, which enables violence against it in a patriarchal society.’

Azar reclaims agency in the landscape. Resilient, pervasive, and sometimes invasive, vegetable life is stronger than you think. Plants are survivors. Rooted to the spot, they must understand and adapt to their environment in nuanced, sophisticated ways. Their astounding sensory capabilities are only just beginning to be understood and formulated by the scientists who study plant intelligence (a far cry from Backster’s claims of plant telepathy, but nonetheless intriguing).

A solitary practitioner, ‘I always use plants as stand-ins for people,’ Azar tells me. Until recently, the human body was only represented by proxy in her work, but lately, her own body has made an appearance. As the Plantoid, she draws connections between her body and the gendering/Othering of the landscape. Affixing petals and leaves to her body to become the Plantoid, Azar’s self-portraits recall Ana Mendieta’s feather-adorned bodies. Spots and patterns erupting from her skin, Azar’s body becomes variegated, like the leaves of her plants.

In the mysterious second part of Kang’s novel, Yeong-hye’s brother-in-law, an artist, paints her nude body with flowers and leaves—a sexual fantasy for him, but a moment of actualization for Yeong-hye. Seeing herself painted like a plant furthers her resolve to become one, freed from the constraints of society. Her transgressions, however, eventually find her institutionalized, and in complete withdrawal from human contact. Her bloody dreams continue to torment her, as she refuses all food—sure in the belief that all she requires is air, sunlight, and water. In an interview, Kang describes Yeong-hye’s denial of the needs of her human body as a refusal of violence and cruelty, at the root of which ‘lies a deep despair and doubt about humanity.’

In light of recent events—the chorus of climate-change-deniers and apologists in the wake of the horrific devastation of Hurricane Harvey, the terrifying white supremacist uprising in Charlottesville—despair and doubts about humanity seem well founded. Yet, while Azar might personally relate to that, it is hope that lies at the root of her work. ‘I think my work is definitely less “angry” than I am,’ she confesses, ‘since I mainly used to make work because I wanted to create beautiful stuff as a way to get out of my own mind.’

For Azar, plants serve as a refuge, a solace, and a backdrop for memories. ‘I never thought I could keep a plant alive but tending to them has improved my mental health,’ she says, ‘It’s very therapeutic.’ We can learn a lot from plants, clearly. Azar speaks about their ‘simple needs’—sun, water, care—and the symbiotic relationships they uphold between different forms of life on the planet.

Whether it is possible or not, Yeong-hye becomes more plant-like as a means to escape the cruelties of being human, as a return to innocence in a way. In much the same way, Azar dreams of ‘a world where the Plantoid multiplies and flourishes, regardless of forces that work against it.’ In the face of a society based on violence, greed, domination, oppression, apathy, hatred, and denial of all of the above, this beautiful vision is perhaps one we can all hold on to. After all, once we’re all long gone, Earth’s plant life will still be here and will find a way to thrive.

All images: Roxana Azar, Plantoid, 2017