Got a deadline looming? Someone chasing you for an important email, or just a phone call you need to return? Chances are, you’ll deftly bring up Instagram, Twitter or Facebook on your phone and start scrolling; anything to avoid the task ahead. The more urgent the job, the more likely you are to procrastinate. While Instagram, with its image-led feed, has long been lauded as the art world’s distraction of choice, there has been a quiet revolution brewing over on Twitter.

A host of art bots are wordlessly shaking up art history, putting out randomly generated images from sources as diverse as Mark Rothko’s colour abstracts to Hieronymus Bosch. Together, they offer a refreshing, poignant view on visual culture, filtered through the distinct lens of the Internet—in all its weird, rude and downright hilarious iterations.

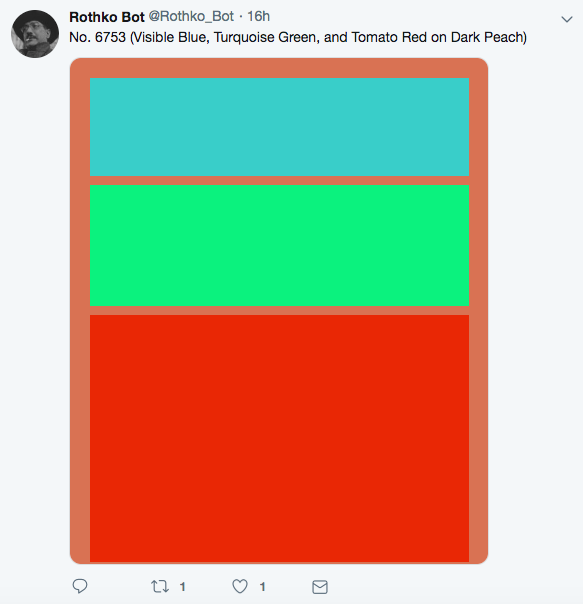

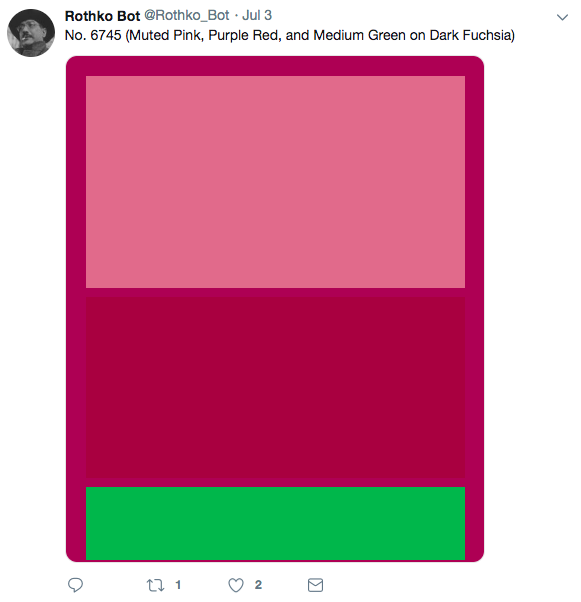

One of these curious automated accounts is Rothko Bot (@Rothko_Bot), created in the summer of 2017 by Zachary Davis in the downtime between graduating and starting his job as a computer engineer. “It selects three or four colours, randomly generates the dimensions of the squares that exist in the foreground of the images, and tweets out a unique creation every two hours,” he explains. It took less than one hundred lines of code to build, and has been running continuously for about two years now.

Inspiration for Rothko Bot came from a few different places. “I had seen some pretty neat Twitter bots in the past that did things like tweet out song lyrics or write short stories by pulling from a large corpus of verbs and nouns. My favourite example of this is @MagicRealismBot. Generative or algorithmically generated art has always been fascinating to me.

“Musicians like Brian Eno and artists like Harold Cohen have built mechanical and computer systems to create really stunning works of art. Given all of that, I wanted to build a fun Twitter bot that would periodically create new and unique works of art. Mark Rothko is one of my favourite artists of any medium, and I thought the visual structure of his works could be something that a bot could procedurally generate.”

If there’s one thing that the Internet does well, it’s the radical reshuffling of high and low culture, mixing the serious with the silly. Similarly, “combining art and technology goes against the ‘right brain vs. left brain’ way of viewing the world”, as Davis puts it. “Things that are vastly different on the surface (like a painter that died in 1970 and a massively popular social media website) can be combined in new and unique ways that would not be possible without modern technology.”

While accounts like Rothko Bot may seem frivolous, they speak to a wider movement towards digitally generated art. Just recently, a painting generated by an artificial neural network sold for $432,500—nearly forty-five times its high estimate—as Christie’s became the first auction house to offer a work of art created by an algorithm.

“Just recently, a painting generated by an artificial neural network sold for $432,500—nearly forty-five times its high estimate”

One of the newest bots on the block is inspired by Dutch artist Piet Mondrian; operating under the handle @BotMondrian, it was launched just last October. Four times a day, the account generates digital interpretations of Mondrian’s work in primary colours of red, yellow and blue. More intriguing is the process behind the making, which is based on the weather in Saint Paul, Minnesota.

There’s even the option to toggle the conditions on a separate GitHub page, revealing the code that connects, say, hotter weather with more occurrences of red in the painting. Sunnier conditions equals more yellow, while rain makes for a leaning towards blue. Carefully considered and truly absurd in equal measure, Mondrian Bot is a quiet work of genius.

Other bots take a different approach to art history, working not just with generative digital images inspired by the original but the real thing itself. Accounts like Bosch Bot (@boschbot) and Bruegel Bot (@bruegelbot) are trawling through iconic paintings with one simple aim: tweet out a random section of these artists’ oeuvre—every hour, every day.

Bosch Bot focuses on The Garden of Earthly Delights, the crowning glory of the Dutch master, a strange, surreal and frequently sexually explicit painting. Measuring almost four metres wide and two metres high, it is a work best viewed up close in order to observe its many bizarre and brilliant details, from fruit delicately balanced on naked bodies to curious demons emerging from the shrubbery.

“If there’s one thing that the Internet does well, it’s the radical reshuffling of high and low culture”

IT consultant and sheep farmer Nig Thomas is the brains behind Bosch Bot, which reportedly took just thirty minutes to build: “It’s the simplest bot I have made—just a few lines of code,” he told Wired last year. “The combination of comical and disturbing is pretty compelling but even given free rein to explore, you miss bits. It’s just too dense.” The account offers an alternative view of the painting, one snapshot at a time. Rather than making the trip to the Prado Museum in Madrid, where the painting is housed, idle procrastinators can find snippets of Bosch’s vision integrated into their day-to-day online scrolling.

Bosch Bot has built up a loyal following of almost 35,000, who will retweet, comment and caption the images generated by the bot, while Bruegel Bot currently boasts 10,000. One caption on Bosch Bot, on an image of a writhing mass of nude bodies, reads, “What are you doing after the orgy?”; another, “Comin’ out of my cage and I’ve been doin’ just fine, fine”.

By posting to a platform like Twitter, art bots are able to build a new, networked outlook on art history—one that stretches far beyond visitor numbers to museums. In doing so, they embody and carry forward the unique ability of great art to be intensely personal while also speaking to a wider, universal human condition.

Tiny Gallery, meanwhile, keeps things small-scale. There are no great masterpieces to be found on this bot’s account. Instead, every tweet displays a box built from a series of hyphens, giving a completely different, visual spin on Twitter’s usual focus on text. Together these lines form a white cube gallery of sorts, albeit in the virtual realm. Their exhibitions? Emoji: from a snowy mountain peak to a billowing rainbow, these little splashes of colour are placed on Tiny Gallery’s walls, elevating them to a newly cultured status. Even the visitors to Tiny Gallery are reimagined as emoji figures, from the dancing lady in red to a pair of male joggers.

“By posting to a platform like Twitter, art bots are able to build a new, networked outlook on art history”

“Lots of the iOS emojis are perfect squares in little tiny frames, and I’d not seen anyone really do anything with them despite the fact that there’s lots of really cute emoji Twitter bots,” Emma Winston, the artist behind the account, explained to Vice in 2016. “I like the idea of messing around with people’s idea of what art and creativity are, of making things fun and making things accessible.”

While emoji have leapt in popularity in recent years, and there have been attempts to rewrite everything from Moby Dick to the Bible in the miniature colourful characters, the concept behind Tiny Gallery remains rooted firmly in the art world, gently poking fun at the airs and graces of the traditional gallery space.

So next time you find yourself idly flicking through your social media, don’t be too hard on yourself. While the Internet might offer a distraction from the daily grind, it can also inspire, transport and surprise in weird and wonderful ways. In the simplest of terms, the rise of the Twitter art bot—created purely for the fun of it—represents some respite from the relentless commodification of the online realm, from data mining to sponsored content. Both pointless and profound, these bots offer a hopeful throwback to a time when the Internet remained a place of utopian ideals.