“Who cares what I do? Who cares what I say? I’m like this, I’ll stay like this, I’ll never change.” These song lyrics by Madrid’s eighties rockstar Alaska epitomised the spirit of a peculiar period in modern Spanish history. Images of Alaska and other celebrities and party-goers from that era are among over a hundred works on display as part of the Rencontres d’Arles photography festival, in an exhibition chronicling the movida madrileña—a radical cultural wave that emerged in Spain in the years following the end of Franco’s dictatorship in 1975.

While primarily a popular music movement, inspired by British punk and American new wave, the movida brought together artists of all disciplines, from painting and photography to film and theatre. The name loosely translates to “the Madrid movement”, and the word movida denotes a disruptive force: something with the power to shake things up.

“After so many years without freedom, the streets turned into a party. There was an urgent need to have fun”

Each of the photographers in this exhibition cast a different light on the period. While Pablo Pérez-Mínguez photographed the famous faces of the day, Miguel Trillo captured the anonymous partygoers of Madrid’s nightlife. Ouka Leele instead chose to photograph people she knew, and Alberto García-Alix’s intimate portraits tackle some of the crucial anxieties of the time, such as hard drug use and the spread of AIDS.

Franco’s fascist regime occupied a chunk of nearly forty years, right in the middle of the twentieth century, and being an artist during this time was risky business. While photographer Miguel Trillo was at university, the police would patrol the campus; public demonstrations were forbidden; Trillo was not allowed to take photos; even having a photocopier was a crime. So, as Spain shifted towards democracy after Franco, the creative world exploded. “After so many years without freedom, the streets turned into a party,” recalls Trillo. “There was an urgent need to have fun.”

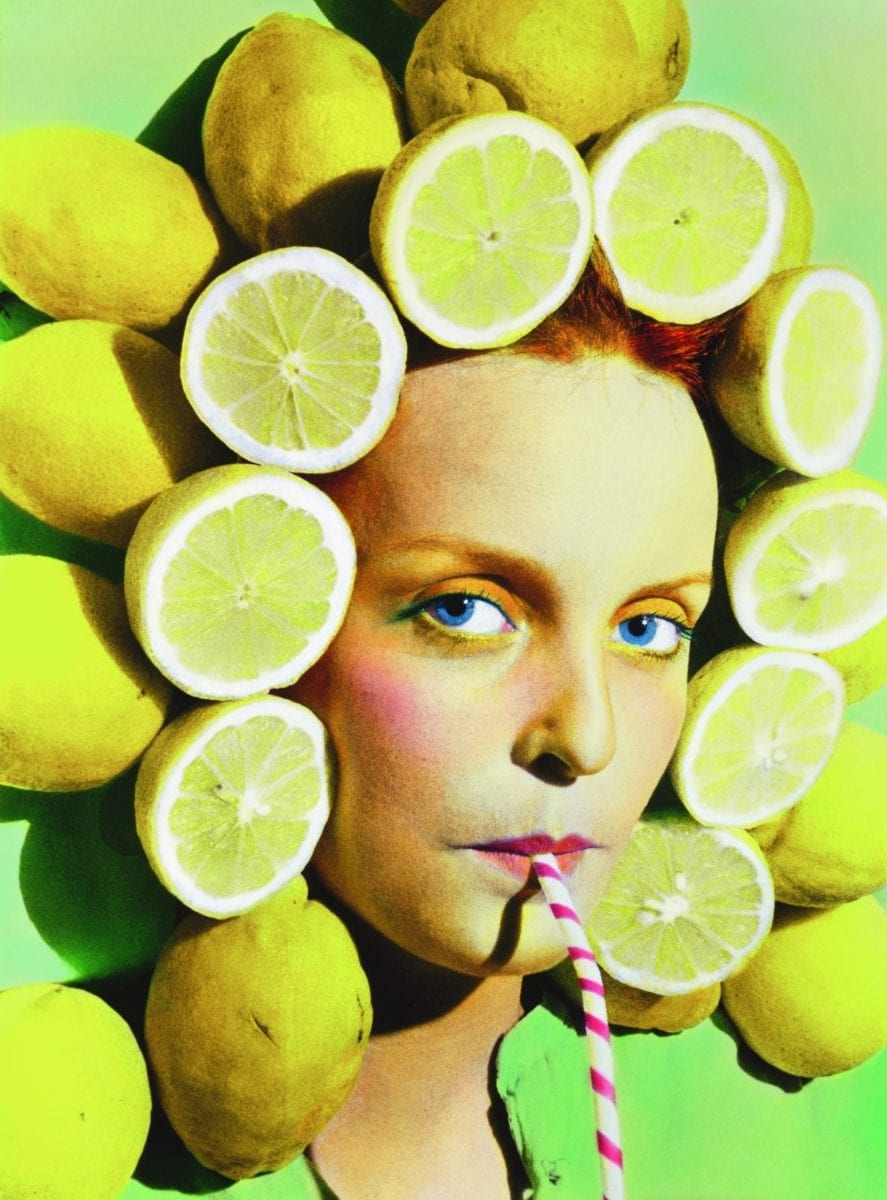

- Right: Ouka Leele, Peluquería, 1979 © Ouka Leele

Fun was certainly a major part of the movida. This period of unbridled cultural, social and sexual liberation was pioneered by the country’s creative community, who were suddenly free to express themselves and generate ideas and debate like never before. “But it wasn’t just an artistic movement,” says the painter-photographer Ouka Leele, “it was a form of utopia. We believed we could change the world and the way we live. We saw property as absurd—we shared everything.”

The year Franco died was the same year that Ouka Leele finished school and embarked on her artistic career. Although she is celebrated today as a photographer, painting was in fact her first calling. “I signed up to photography school out of curiosity, but I never actually planned on becoming a photographer,” she admits. “It didn’t attract me.” Instead, Ouka Leele combined the two practices, painting in acrylic and watercolour over stylized photographs to dreamlike effect. “Photographs normally reflect reality, but I have the vision of a painter—not a photographer. I always wanted to represent my interior world and make paintings out of photography.”

“It wasn’t just an artistic movement. It was a form of utopia. We believed we could change the world and the way we live”

Next February marks the fortieth anniversary of a concert in Madrid that is often thought of as the beginning of the movida. A number of initiatives in Spain are therefore likely to mark the milestone next year; there has even been talk a new museum in Madrid dedicated to the movida. But there are others reasons why this is a moment for Madrid to remember its post-Franco liberation—such as the seats that the extremist right-wing party Vox won this year in Madrid’s city hall and regional government. “There hasn’t been a Francoist party like this in forty years,” says Trillo. “Francoism was erased, democratically; nobody wanted to know anything more about it.”

- Left: Alberto García-Alix Ana Curra esperando mis besos, 1984 © Alberto García-Alix/VEGAP. Right: Ouka Leele, Peluqueria 1979

Many artists of the movida mocked the right-wing Francoism of which the country had just rid itself. The artist duo Costus—one of whom was the son of a Francoist military officer—would make fun of the saintly figures of the Valle de los Caídos (a holy monument built by Franco and where his remains now lie) by transforming them into pop icons.

But although its raison d’etre was largely against the repression of a dictatorial right-wing regime, the politics of the movida are not always clear. The movement also shocked the left side of the political spectrum, such as through its ironic but unashamed use of conservative motifs of Spanish folklore and popular culture. The vocally leftwing Pedro Almodovar, for example, depicted bullfighting in his 1986 film Matador in a way that many others on the left may not have dared.

Rather than left or right, the politics of the movida revolved around one simple concept: freedom. For Ouka Leele, the surrealist Paul Eluard’s poem Liberté (1942) defined the movida’s manifesto. “It was as if everyone wanted something new,” she says. “All social classes mixed together, all political leanings, all ages, backgrounds.” Freedom was, on the one hand, an opposition to the politics that had hitherto curtailed it—but it was also a rejection of politics entirely.

“Young people were suddenly disinterested in politics,” says Trillo. And today, as debate continues over what to do with Franco’s remains—whether they should be exhumed from the Valle de los Caídos, and if so, where to—many from the movida prefer not to get involved. “This is a purely political issue,” says Trillo. “The important thing for us was that Franco was buried. Where his corpse lay was of no interest.”

“Rather than left or right, the politics of the movida revolved around one simple concept: freedom”

But where is the line between political freedom and absence of politics altogether? The disparate political inclinations of the movida’s key figures today suggest the movement lacked political or ideological cohesion. The painter Antonio Villa-Toro has vehemently distanced himself from the ethos of the movida; the artist Fabio McNamara, once a collaborator of Pedro Almodovar, has been vocal about his alignment with the Catholic church; and the singer Alaska, the iconic face of several rock bands like Los Pegamoides and Fangoria, is now known to support the right-wing Partido Popular (PP).

To this day, it is difficult to fit the movida into one political box. Instead, the legacy that prevails is that people from all political directions subscribed to the movida’s promise of freedom—and its true power lay in its irreverent, even frivolous, view on what should or should not be permitted. “It was freedom of coexistence between people of different mentalities,” Trillo explains. “Nobody wanted to prohibit anything—prohibition is what we had just come out of.”

La Movida: A Chronicle of Turmoil

At Rencontres d’Arles until 22 September, and then at Foto Colectania in Barcelona from 18 October until 16 February 2020

VISIT WEBSITE