“I sometimes feel as though I have said and heard enough. I cheer the blank page. And central to my own work has always been the fact that women have more than one pair of lips,” the artist Linder Sterling, known simply as Linder, once stated in an interview with her close friend Morrissey.

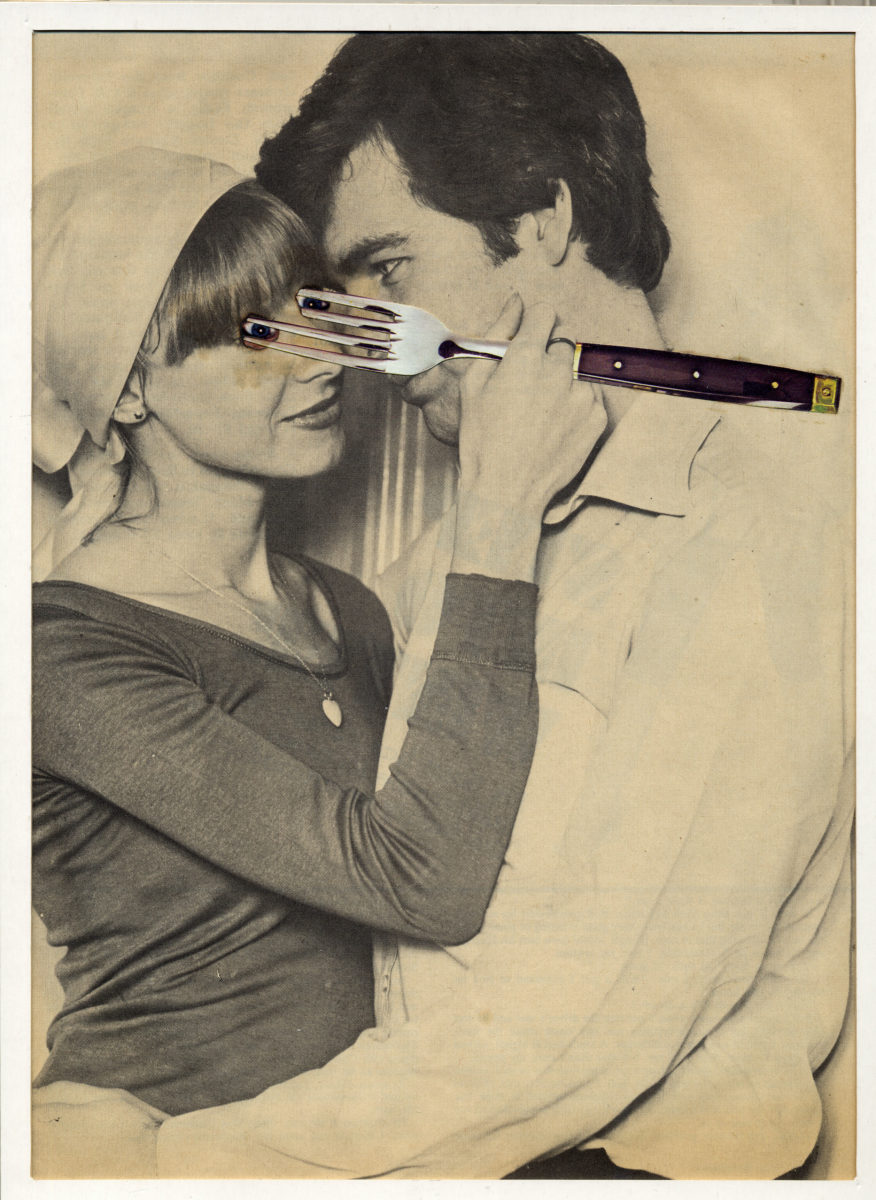

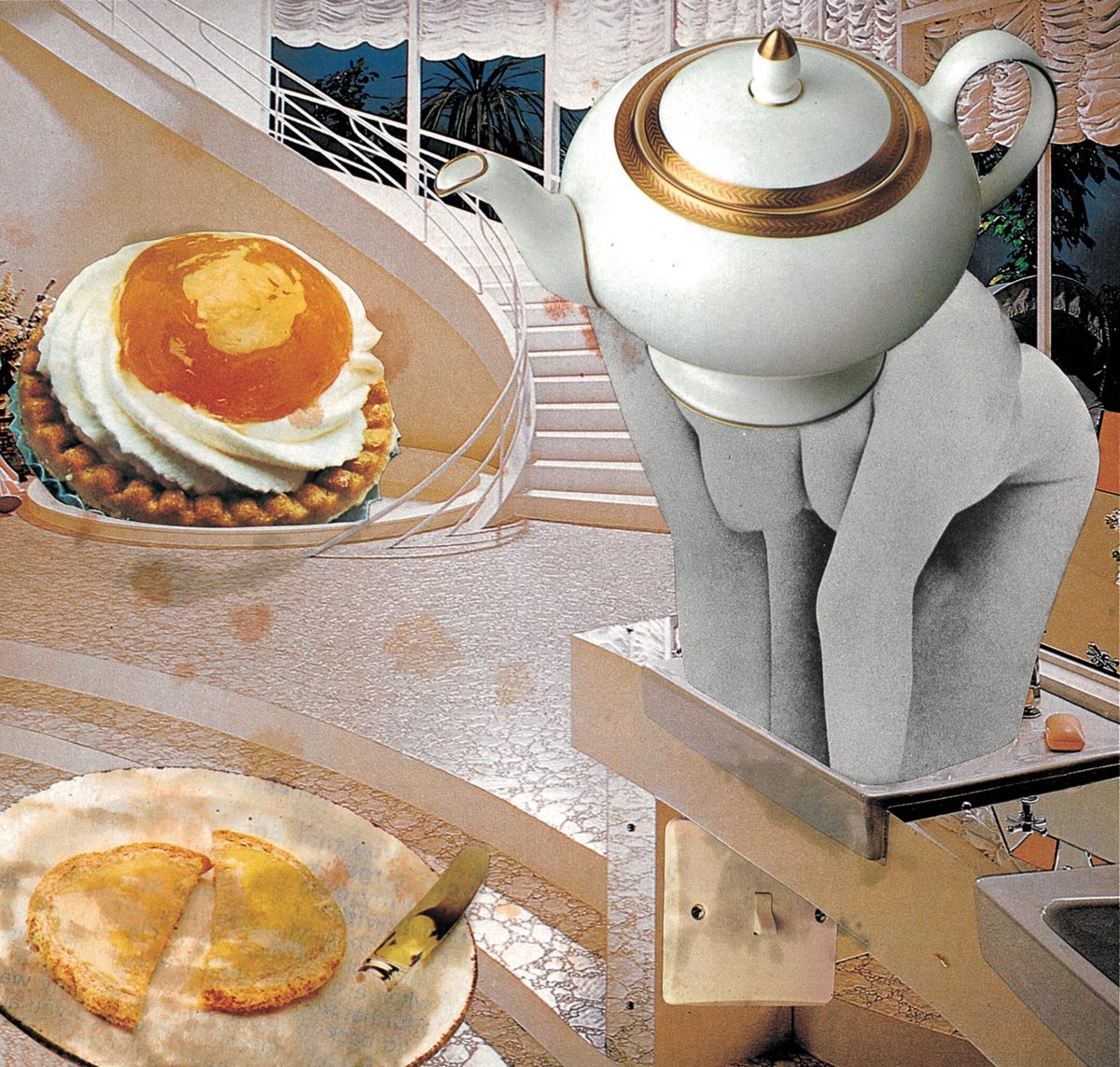

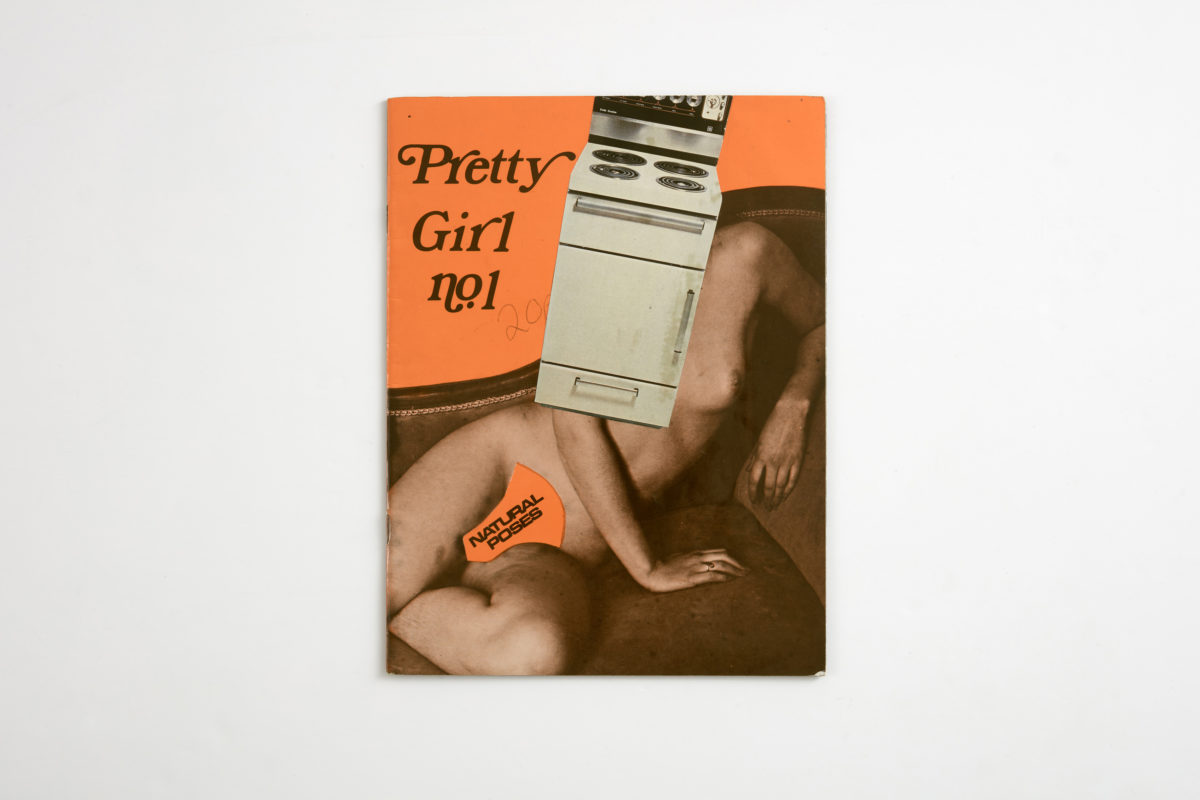

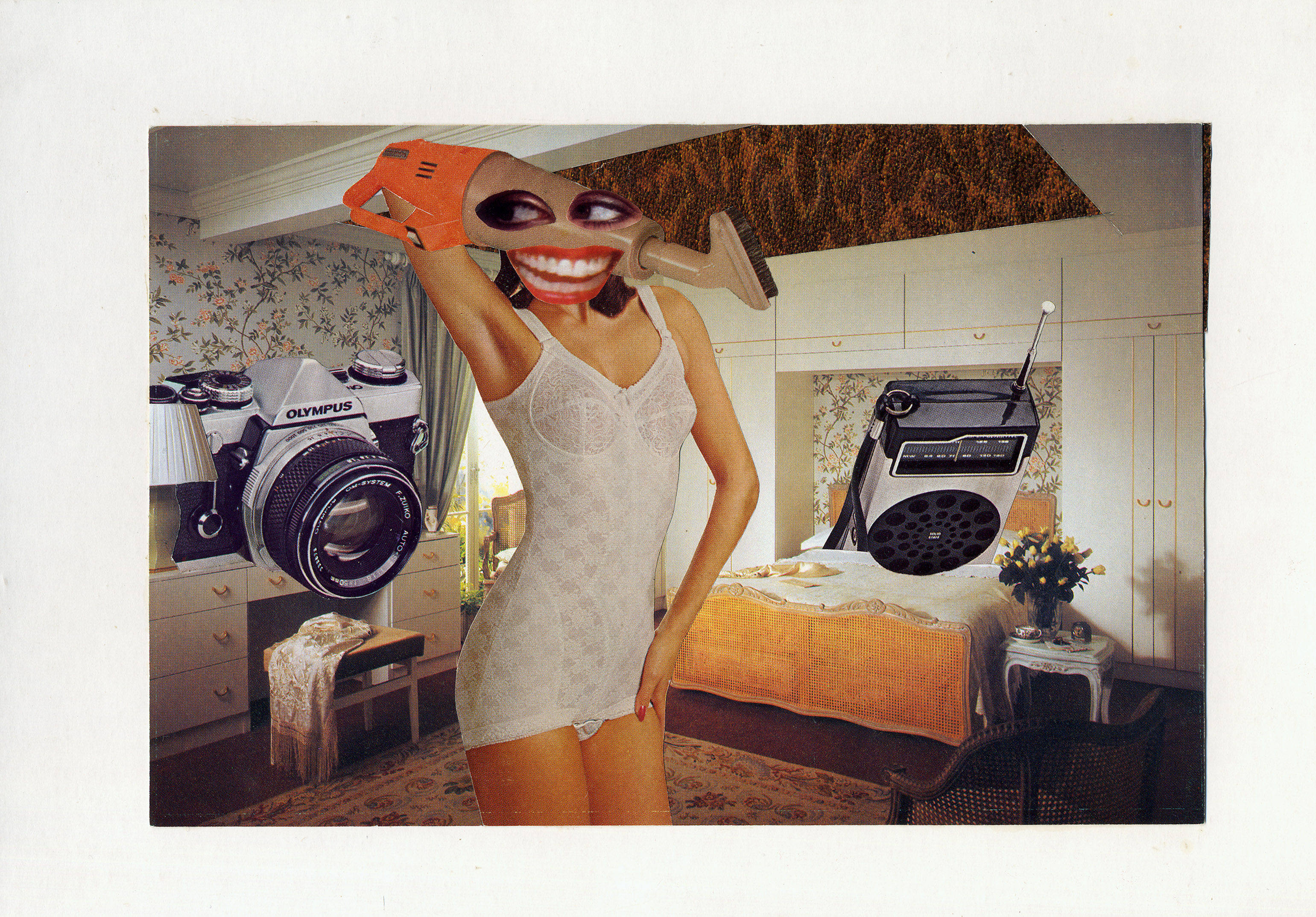

In the late 1970s, when Linder started her first photomontage series, the magazine market was unabashedly gendered. There were magazines for men and magazines for women: for men, it was cars and porn; for women, it was the home and fashion. Linder’s simple yet brilliant conceit was to cut and paste the two together. The juxtapositions she assembled were revelatory: forms that were free of gender, and which vyed with convention—both sexual and sensual.

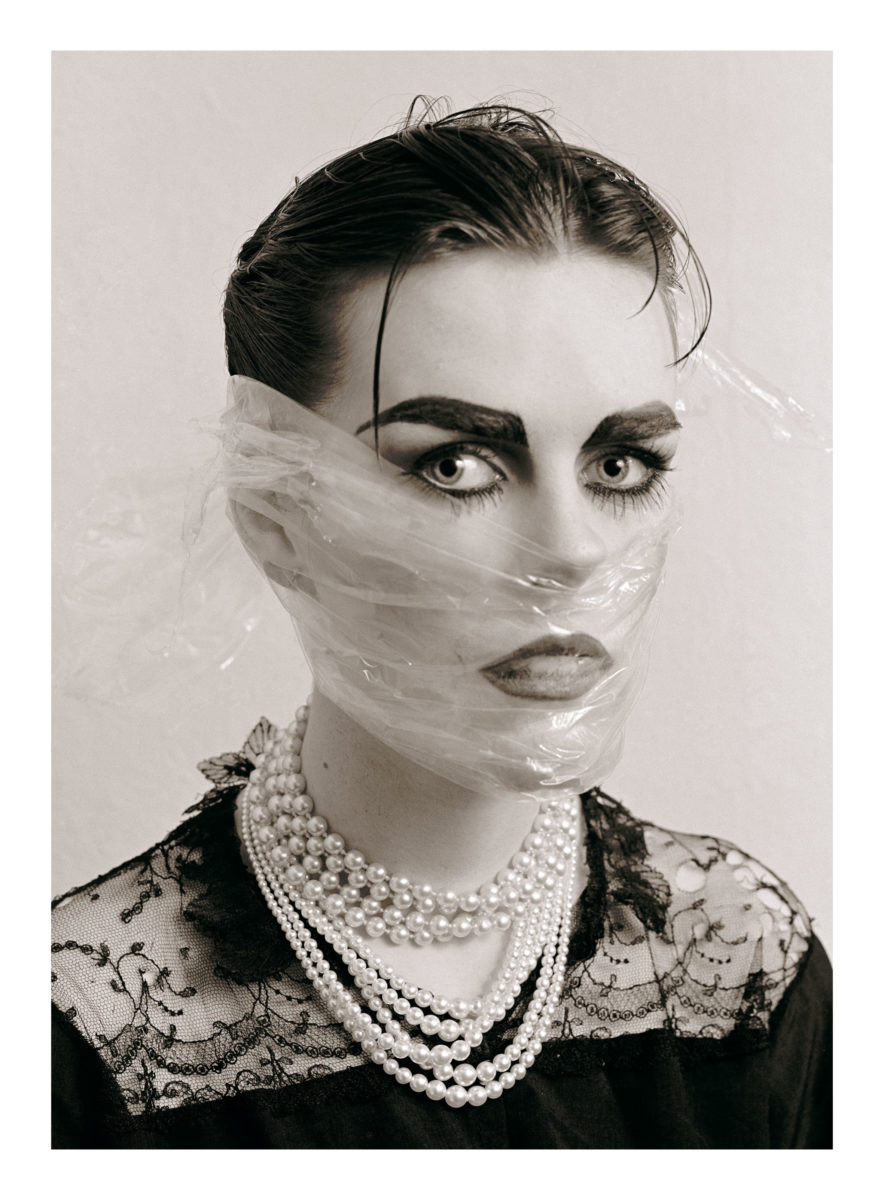

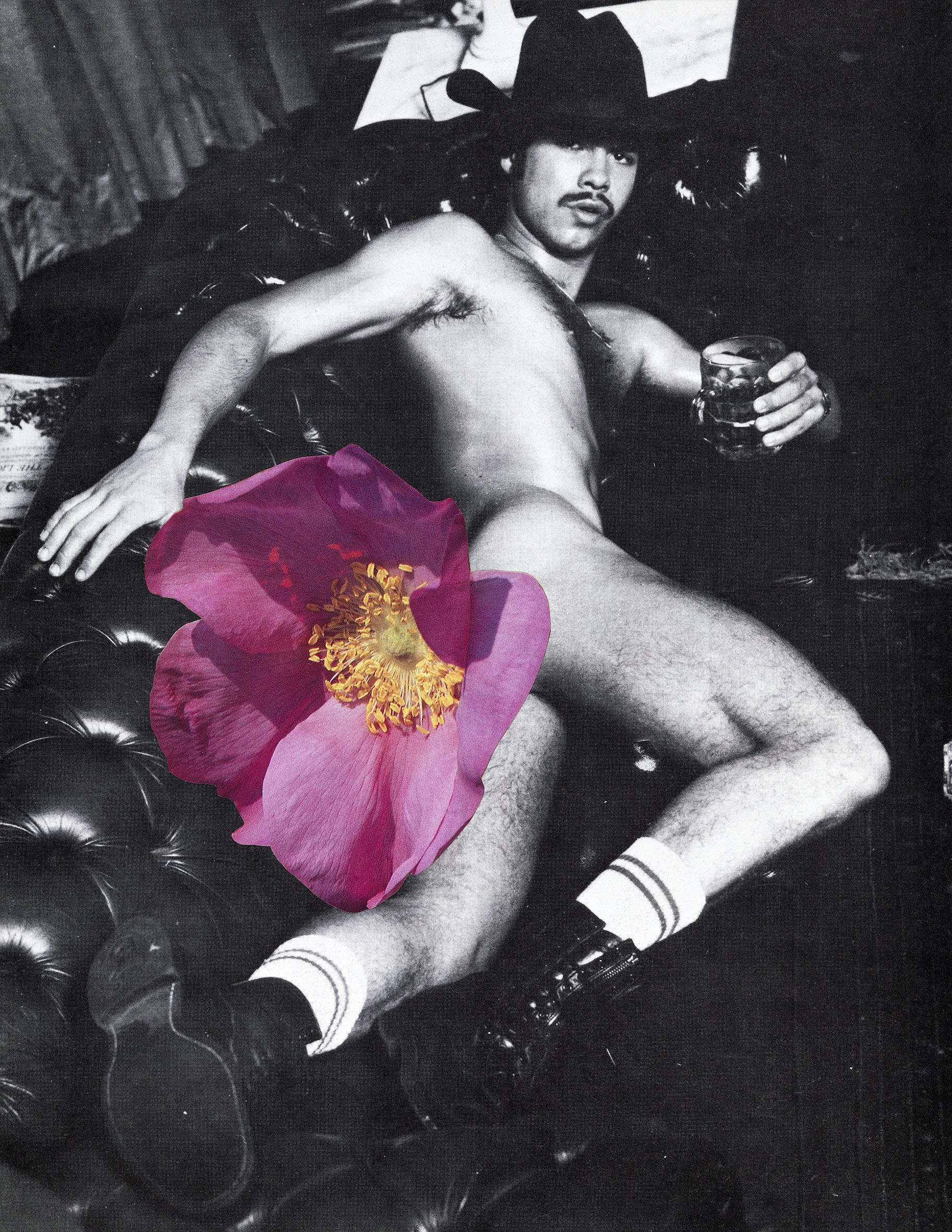

Gender fluidity, feminism and sex have been at the centre of Linder’s work ever since. By rearranging the images and forms from mass, mainstream print culture, Linder showed up the contradictions and conflicts in modern visual language. In 1976 she was already making women straddle lipstick, and replacing their heads with vacuum cleaners, an absurd indictment of the way women are conditioned to consume, even as they reduce themselves to product. Though Linder’s focus has predominantly been the slick, glossy, pruned bodies of pin-ups, found-images of dancers and models, or even herself, men haven’t been spared her scissors either; an erection becomes a hoover, an asshole blooms into a gorgeous rose. We are all, in the end, inferior to interiors.

Linder’s long-standing and personal relationship with British punk, and some of its most famous musicians, has made her something of a 1970s legend. She was only in her twenties when she created the now-iconic cover art for the Buzzcocks 1977 single Orgasm Addict; she was well-known on the scene in Manchester and Liverpool especially, and started her own post-punk group in 1978—she performed in dead meat and dildos. With the subversive, fast and frivolous energy of her art, Linder’s affinity with punk was natural. But there was also more to it than youthful dissent and shock value for laughs.

“Central to my work has always been the fact that women have more than one pair of lips”

Though Linder has worked continuously since, in the 2010s Linder’s work has seen something of a revival: she collaborated on a ballet performance in response to Barbara Hepworth which took place at the Tate St. Ives and the Hepworth Wakefield, and had solo exhibitions at prominent spaces in Paris, London, LA, Glasgow and Nottingham. In 2018 she also created an eighty-five-metre long billboard, The Bower of Bliss, at Southwark Station for Art on the Underground. This visibility has introduced a whole new audience to Linder’s purposefully political, fully-frontal feminist works. Her investigations into the way women are treated by and in visual culture, for profit and gain, whether they are erased or over-exposed, have only become increasingly relevant since the 1970s and its radical feminist canon.

The time is ripe for her latest exhibition, unabashedly titled Linderism, opening on 15 February at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge. Typical of Linder, it promises to be an experience for several senses at once, with interventions in the cafe and the scent of a special, historic potpourri once adored by Kettle Yard’s founder Jim Ede. Linder has even reinvented the staff’s uniform. On the aural front, there’s a sound installation in what was once Ede’s wife Helen’s bedroom, made in collaboration with Linder’s son.

There is also a new photomontage work based on Helen Ede’s image. Ede’s material absence became a concern for the artist when researching the space and its history. Linder has even gone full circle and created a line of products (including scented candles, fabric squares and notebooks) in Helen’s name, available to buy. Commodity, after all, might be the only language that we can all really understand.