“My girlfriend is about to give birth!” my boyfriend shouted urgently into the phone. From my position on all fours on the bed, I rolled my eyes. “Ask them if I should come in yet. Tell them I’m having contractions,” I rasped.

I knew it was going to be bad. I just didn’t realize how bad. It was nothing like Queen Elizabeth’s birth scene in The Crown, there was no “ping” like in Monty Python and it definitely wasn’t like I saw it in the 1990s (Julianne Moore being attended to by Robin Williams in Nine Months? Nope). It didn’t look like any of the medieval birth paintings, nor a Heji Shin photograph (from my viewpoint, at least).

We arrived at the hospital waiting room, me sweating, with a blanket over my head. Another woman was in labour, straddling three seats, howling, her partner nervously rubbing her back.

“I can’t do it, just cut it out of me!” I cried, seven hours later, after twenty-seven hours in labour. The pain was at times terrifying, and the scariest thing was there was no way out; my body was acting of its own volition and I couldn’t control it. This was supposed to feel natural, “our bodies are designed to do this”, etc, etc. The words I’d learned in my hypnobirth course haunted me. It felt to me like a trauma that my body couldn’t cope with, and that it was impossible there was enough room for a human to come out of it.

Nonplussed, my boyfriend and the midwife gently offered encouragement as I writhed around like a wild animal in the birthing pool. I couldn’t communicate except in sounds that came from some primitive, cave-woman version of myself, but heard snippets of their conversation about the poor quality of hospital coffee. “You’re almost there,” they kept telling me. When the head was finally “visible”, somewhere up there, I thought that must surely be the end. “How long now?” I pleaded. “It’s usually about two hours from here,” came the calm reply. Expletives, gritted teeth, tears.

“I felt overwhelmed by a gentle wave of calm. She was going to have a happy and good life.”

As the tiny purplish person, perfectly formed, resembling my dad, was finally placed in my arms, quiet and blinking up at me with a wise look, I experienced something I have never felt before. But it wasn’t a spiritual awakening or the fireworks of a prise de conscience. As the little thing looked straight into my eyes I felt overwhelmed by a gentle wave of calm. She was going to have a happy and good life. She was going to make me a much better person. It felt natural and normal that she was here in the world now and we were part of each other, and would carry on together.

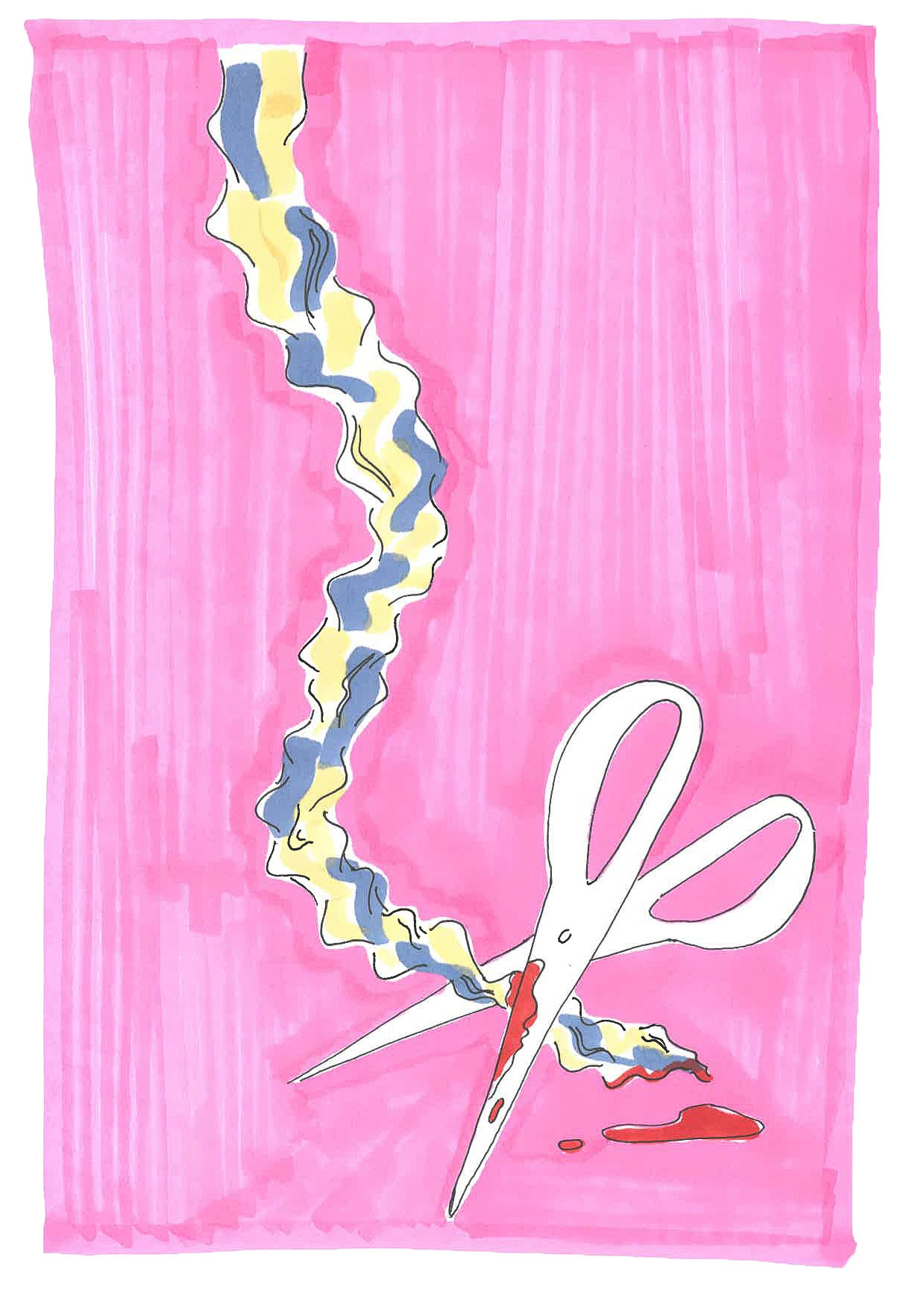

Soon enough practicality kicked in, as it inevitably does. I began to feel sorry for the little purple wonder in my arms, our untainted specimen of humanity spending the first minutes of her life sitting in a lukewarm pool swirling with blood and bits of faeces. My boyfriend cut the cord (a thick, liquorice-like thing) and took the babe in his arms, while I waddled out of the water and across the room, dragging the rest of the cord, scissors attached to the end, like the protagonist of a David Cronenberg movie. Awakening from my birth trance, I came over all British, apologizing to the midwife, who had just moments before been fishing bits of my poo out of the water with a mini fishing net, for the strange noises.

But that wasn’t quite the end of it.

An hour later a slab of meat the size of a Hawksmoor steak came out (not without another excruciating effort) and then a theatre bed was wheeled in for the finale: stitches. The midwife then on duty thought it a good chance for her junior to practise. “Er, maybe you could finish it?” My boyfriend nervously called to the senior nurse from a safe distance across the room.

“No one wants to hear about the grisly stuff. And, of course, no two births are the same.”

Once I had recuperated enough to hold a phone I called my sister. “How could you not have told me how bad it is?!” I levelled at her. “Well, it wouldn’t really have helped, would it?” I understood then that there is a code among mothers to not talk about birth experiences, at least not in gory detail. There’s a collective reluctance to talk about something so individual and basically indescribable. No one wants to hear about the grisly stuff. And, of course, no two births are the same. But isn’t this partly self-imposed taboo, a bit like our society’s attitude towards menstruation, another way of repressing women’s bodies, making them seem cleaner, neater, more sexual than they really are?

When famous artists do make direct works about birth, they often become their least known: Frida Kahlo’s imagining of her own entry to the world, My Birth, is rarely seen printed on mugs and postcards like her other self-portraits. Judy Chicago’s 1980-85 Birth Project, a collaboration with 150 needleworkers, was a literal attempt to create a tapestry that could reflect the gamut of birth experiences and address the apocryphal tales about birth in pop culture—but it’s been forgotten, eclipsed by her more palatable dinner table. As an observer of art, I’m constantly amazed by creation, yet the physical processes of women’s bodies seemed to me until my own experience to be run-of-the-mill, something so many people do that it must be ordinary.

I can’t say I felt empowered as I shuffled out of Homerton Hospital with my baby, my boyfriend, my deflating balloon of a belly and my NHS designer vagina. But life suddenly seemed more remarkable than ever.

Illustration by Rosalind Duguid

Out Now: Issue 37

BUY ISSUE 37