Admittedly, I was excited when I heard that Jessica Silverman Gallery was going to be showing never-before-seen work by Judy Chicago. But then I was worried to see cat paintings were included—this is Judy Chicago, of The Dinner Party (1979) fame. What have we become? To traverse from monumental work about art history, women artists, male hierarchy, white male dominated art world, gender inequality—the list goes on—to cats. ‘This is a low time, we’re stepping backward,’ I thought… and simultaneously, ‘I have to see this.’ The show, Judy Chicago’s Pussies is not, but is about “her” various pussies.

In the main gallery are several abstract works referencing proverbial and actual pussies; they each show the power and discomfort that seemingly innocent geometry can convey when equated with the female body. The colloquial use of the word ‘pussy’ is controversial: it’s a derogatory term used toward men who don’t operate within hetero-normative social behavior, and it is also an endearing or pejorative term (depending on context) for a woman’s vagina. Chicago’s objective is to bring to light the “absences in art history about women’s experiences,”she said at the press preview I attended. Seeing this work for the first time, getting a glimpse into her practice and knowing others are too, is exhilarating not only for historical significance but for its timeliness: it’s always a good time to talk about women in society, be it the art world or otherwise.

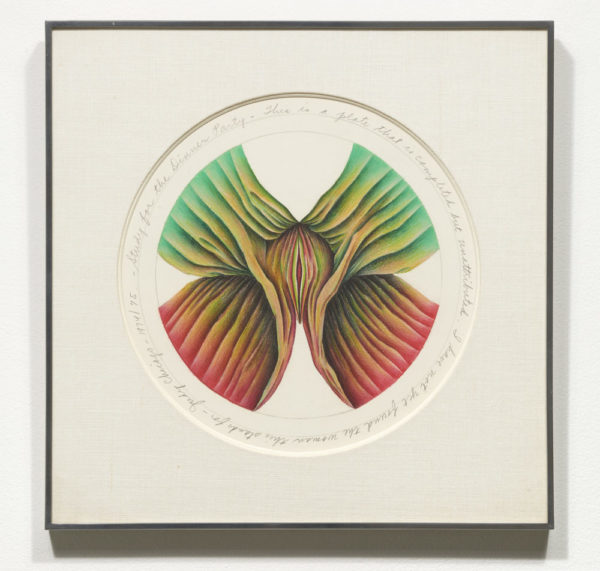

In the main gallery are three vaginal plate studies (1973-1975) developed during the making of The Dinner Party illustrating Hrosvitha, an 8thcentury German nun who wrote plays representing women as strong beings, powerfully steadfast compared to weaker male characters full of lust. On the wall are three black Prismacolor drawings titled Potent Pussy (1973)—abstracted mandala-like drawings removed from Chicago’s personal sketchbook and framed for display. In each, rigorous examinations of op-art in a composition of petal-like shapes expand from a radiating center. An actual page from the journal includes text handwritten by Chicago alongside Potent Pussy sketches; she recalls asking a female colleague if “they look like cunts.” Having offended her counterpart who was considering the work for a group show, it was never shown.

An even earlier work 3 Star Cunts (1963) is an obvious jab at male-dominated minimalism during that era. Far be it that a man would equate his work with his penis (or title it as such), yet within minimalism’s visual language are all sorts of descriptors that reinforce masculinity: rigid, rectilinear, pillars, towers, hard-edged grids. And with it came a certain power in the art world; to contest that, Chicago’s spirals and circles become minimalism’s “feminine” counterpart, before she made literal vaginas. “Feminism is a way of seeing the world.”

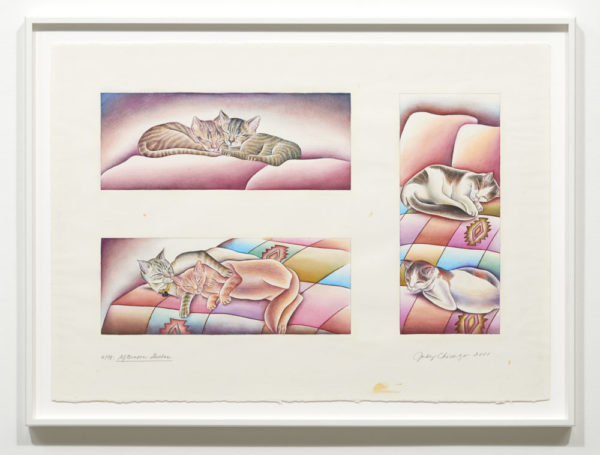

In contrast, the series titled Kitty City (2001) segues from abstracted “pussies” to colorfully illustrated portraits and domestic scenes of Chicago’s and her husband Donald Woodman’s several cats. The works on paper are displayed in the second smaller gallery on bubblegum pink walls. At first glance a rush of superficial reads come to the fore: cute, banal, “cat lady,” but on a serious note there is tremendous detail rendered in unforgiving finite watercolor, deep admiration for living things, and a glimpse into a very personal part of her life. Chicago spent countless hours studying the cats’ behavior, “like a Medieval book of hours.” She would wake up at 2am and photo-document their goings-on: lounging about and any number of things that go on in their daily lives, such as 7AM, Chowtime (2000). Ultimately, Kitty City looks deeply at the concept of animals as sentient beings with personality and feeling; they are metaphors for human nature: bondage, familial behavior, companionship, unconditional love, living life and power struggle.

Chicago explained that the works came about after her HolocaustProject: From Darkness to Light (1985-1993) and her continued examination of human behavior. Charles Patterson cites Chicago in his book, Eternal Treblinka: Our Treatment of Animals and the Holocaust: “After she began to see the slaughterhouse-like aspects of the Holocaust, she [Chicago] started to understand the connection between industrialized slaughter of animals and the industrialized slaughter of people.” She corroborated: the Nazi regime continuously referred to Jewish people as ‘pigs,’ thus dehumanizing them, and substantiating their rationale for extermination. “Humans beings are the only cruel animals on the planet,” she said.

The art world and the ideals and rules of Western global economics are still dominated by white cis males, and the mass “accepted male definitions of some things as ‘universal.’” Woodman chimed in about feminism at one point during Chicago’s discussion at the preview: the 70s were a time of separatism, whereas the 80s presented a different kind of “power play,” and now we are seeing discussions about gender fluid “value systems.”

“If anything, Chicago is teaching us that all subjects are worthy of making art about feminism, all subjects are fair game when talking about feminism.”

Chicago mentioned that she is tired of educating people about her work. I think the frustration comes from the fact that we still need to talk about this stuff, and we can’t completely move on to general humanitarian topics while there are still women and marginalized people at a competitive disadvantage. If anything, Chicago is teaching us that all subjects are worthy of making art about feminism, all subjects are fair game when talking about feminism.

We must keep talking about gender, about disparity, inequality, hierarchy—the list goes on. Along with Carolee Schneeman, Miriam Shapiro, Rachel Rosenthal and other feminist art icons of her generation, she is not timid about putting forth provocative images and language—she continues to push against the status quo of what it means to be a woman artist, and to take risks like—painting cats. “My privilege as an artist is to change [how women are represented]. If I was someone who just tried to fit in, I would have been seen as just another artist saying the same old thing.”Let us return to the cat metaphor: if cats are equated with women, then it’s fine time that the ol’ boys club cat and mouse game evolves and women turn the tables—again, again and again as needed. In a sense, her work is still a wake-up call of how we need to get real about pussies, about humanity, about women’s power and feminism.

Judy Chicago ‘Pussies’ is at Jessica Silverman until October 28.