Which would surprise you more: a sexy image of an unclothed woman, or one of a naked man? It is a disparity that remains starkly drawn between the sexes. As the Guerilla Girls pointed out in their 2012 iteration of the Do Women Have to Be Naked series, less than 4% of the artists in the Modern Art section of the Met are women, but 76% of the nudes are female. It doesn’t look much better in the ads on our screens: women were shown in sexually revealing clothing six times more than men between 2006 and 2016, according to research by J Walter Thompson New York and The Geena Davis Institute on Gender in Media, for which they partnered with Google to analyse its data.

Elephant has long championed the reclaiming of female sexuality, such as in Issue 25’s Girl on Girl (now a book by Editor-at-Large Charlotte Jansen, published by Laurence King), focused on women photographing women. It is a more essential undertaking than ever at a time when the gender pay gap is under fierce scrutiny, and when women’s bodies continue to be misrepresented. But what about the erotic identity of the opposite sex?

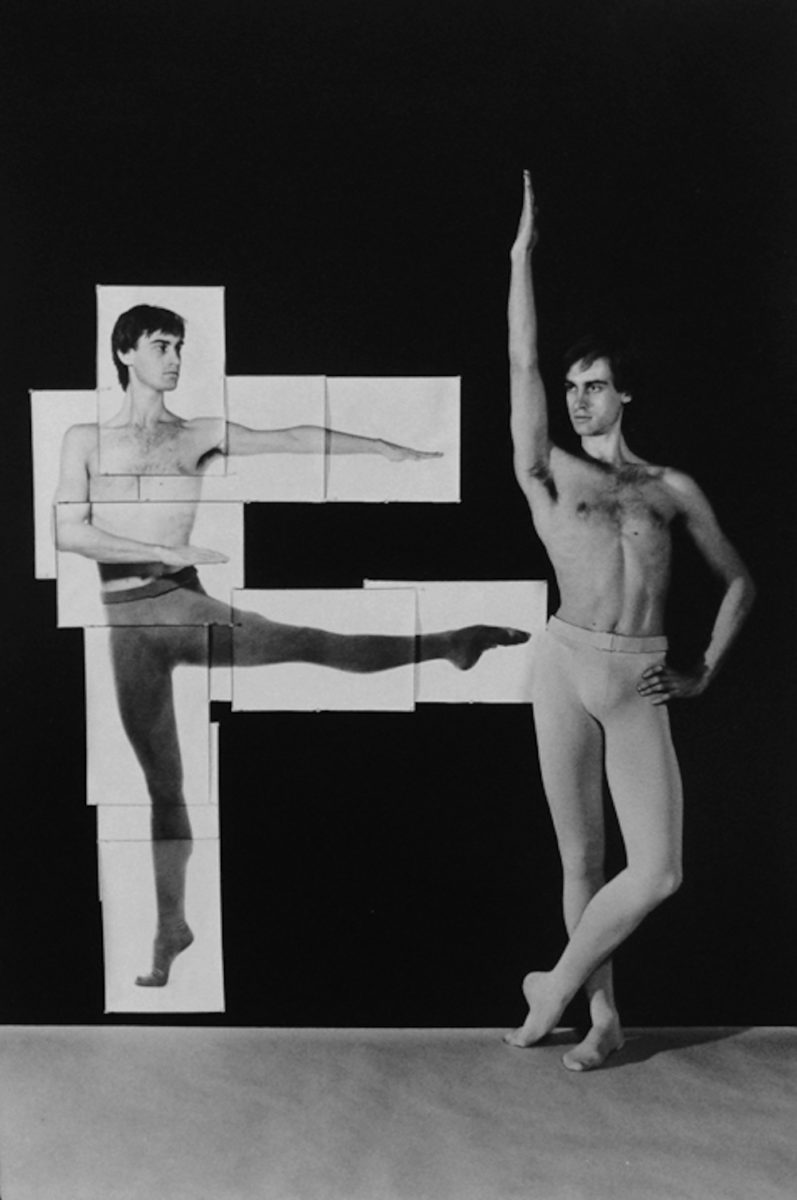

The male form remains reticent in galleries and the media at large, and its appearance can cause something of a stir. Think of Robert Mapplethorpe’s stylized photographs of friends and lovers from the underground BDSM scene of New York in the 1970s, in which men squat and strut in leather and whips. They are at turns violent, assertive and intimately tender––as arresting today as when they were first taken.

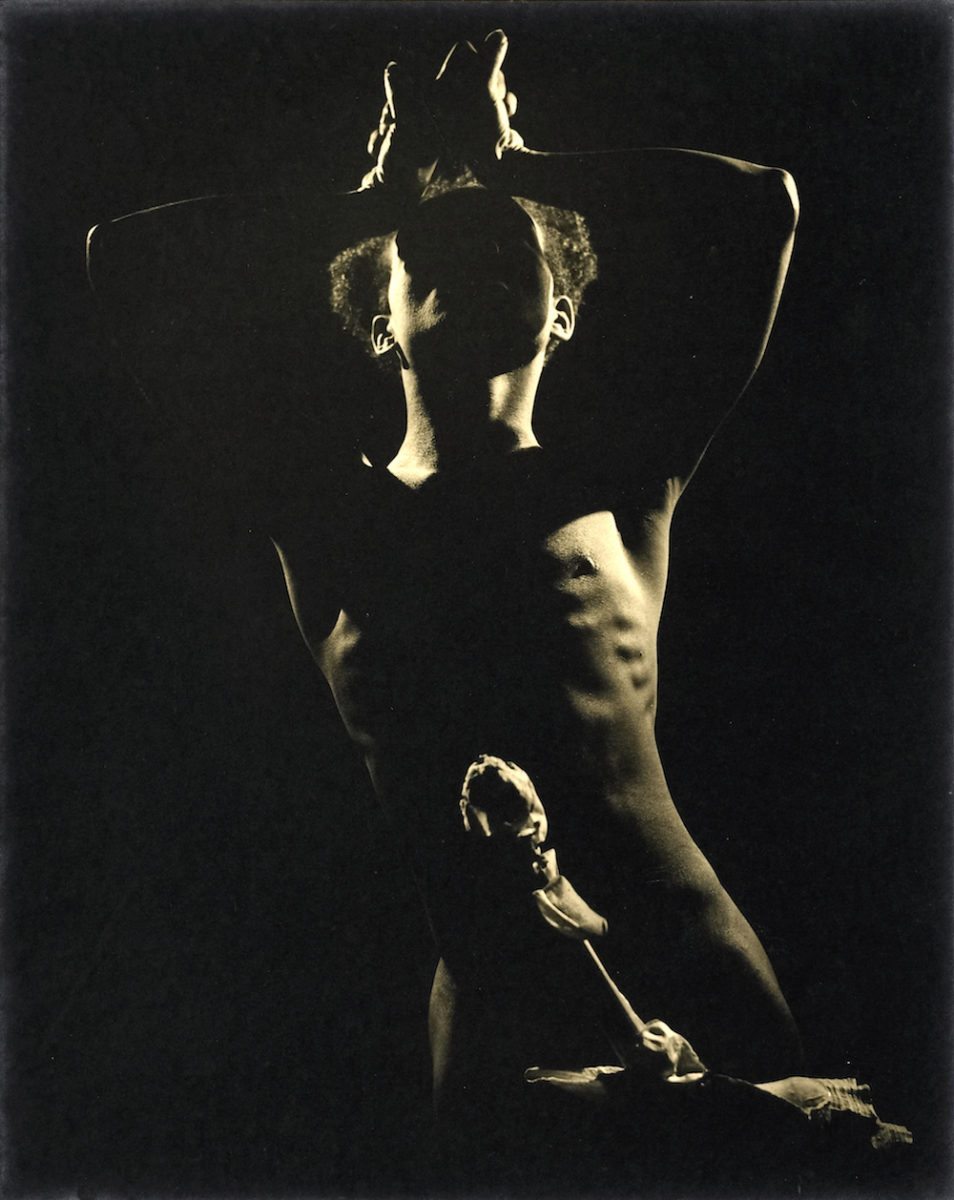

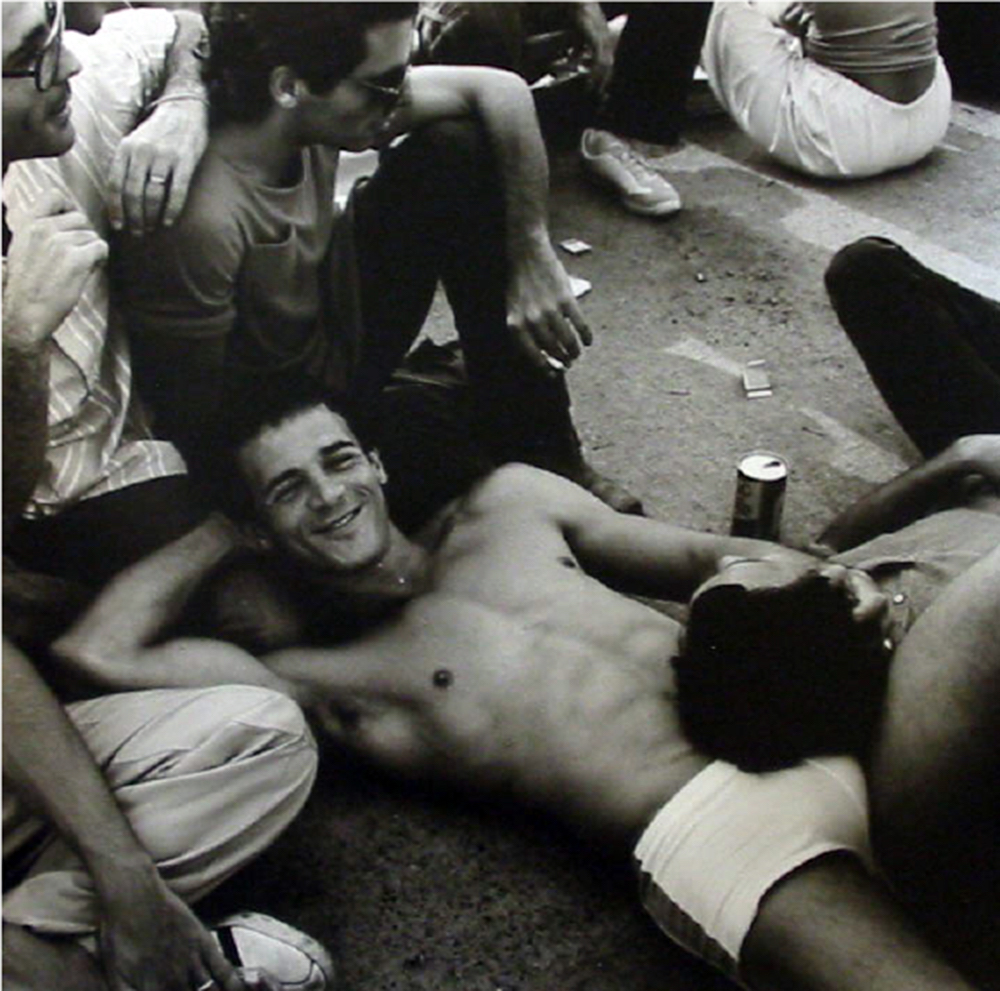

Peter Hujar was another figure on the New York scene at the time, an old acquaintance of Warhol’s who had appeared in several of his Screen Tests. A photographer in his own right, his black and white images of men he met through friends and at New York’s piers are quietly compassionate, his subjects open and at ease. In The Lonely City (2016), Olivia Laing describes how “Hujar looked at his subjects with the eye of an equal, a fellow citizen, […] the tenderness of an insider, rather than the chilliness of a voyeur.

“The erotic male form is too often sidelined, even as women are undressed again and again to the point of ennui”

It is impossible to consider the homoerotic male body depicted by Mapplethorpe and Hujar without touching upon the AIDS crisis that cut through the gay artistic community of 1980s New York––Hujar died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987, while Mapplethorpe passed away two years later. Sarah Schulman called it “the beginning of the end of the world” in the opening sentence of her 1990 novel about AIDS, People in Trouble. The virus tainted the creative energy of the time, taking many long before their time, and is inextricably linked in memory to the raw sexuality that shaped the works of its artists.

The Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art in New York is the only museum of its kind, focused on the preservation and promotion of the LGBTQ visual arts, founded in 1987 in the midst of the city’s burgeoning queer culture. Since then, it has amassed a remarkable collection, spanning several centuries and continents. Little-known and anonymous artists are included alongside figures such as David Hockney, Mapplethorpe and Hujar.

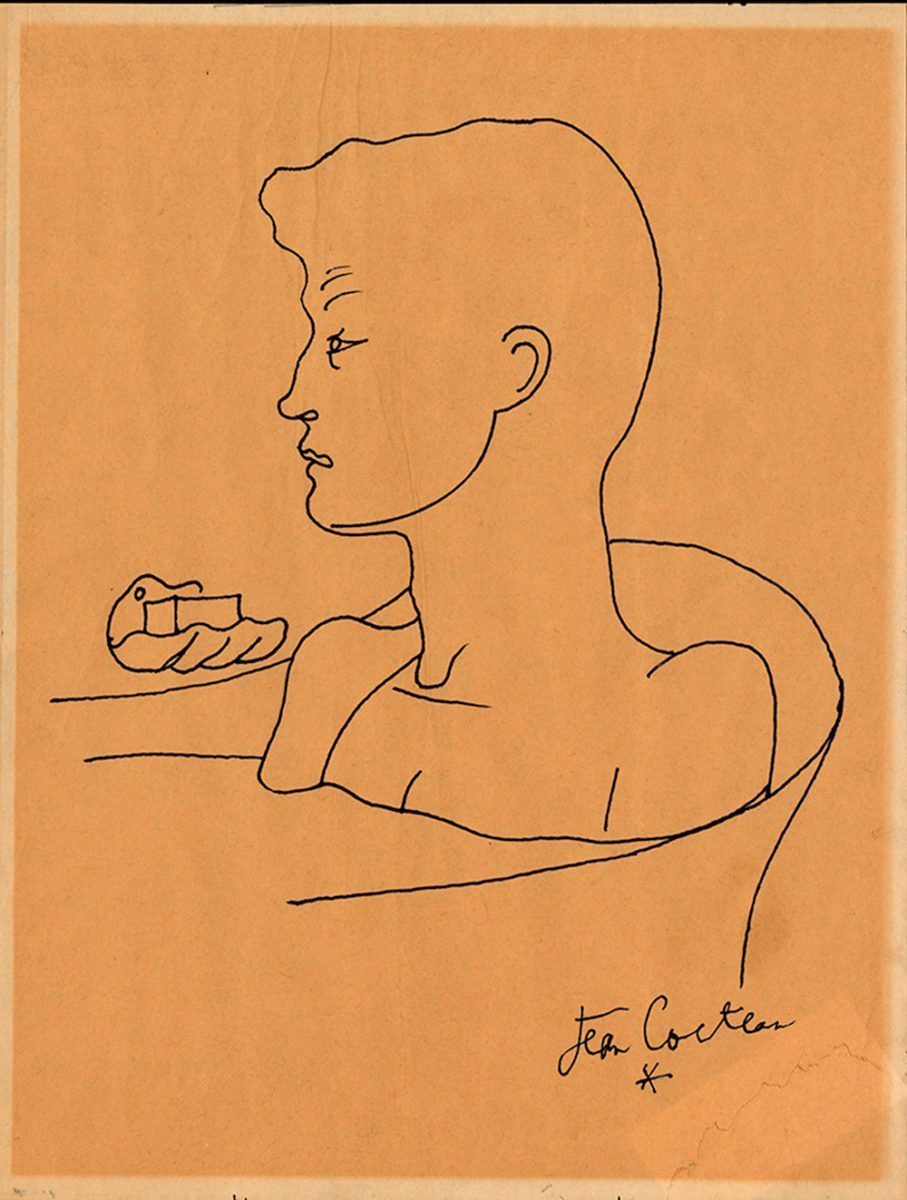

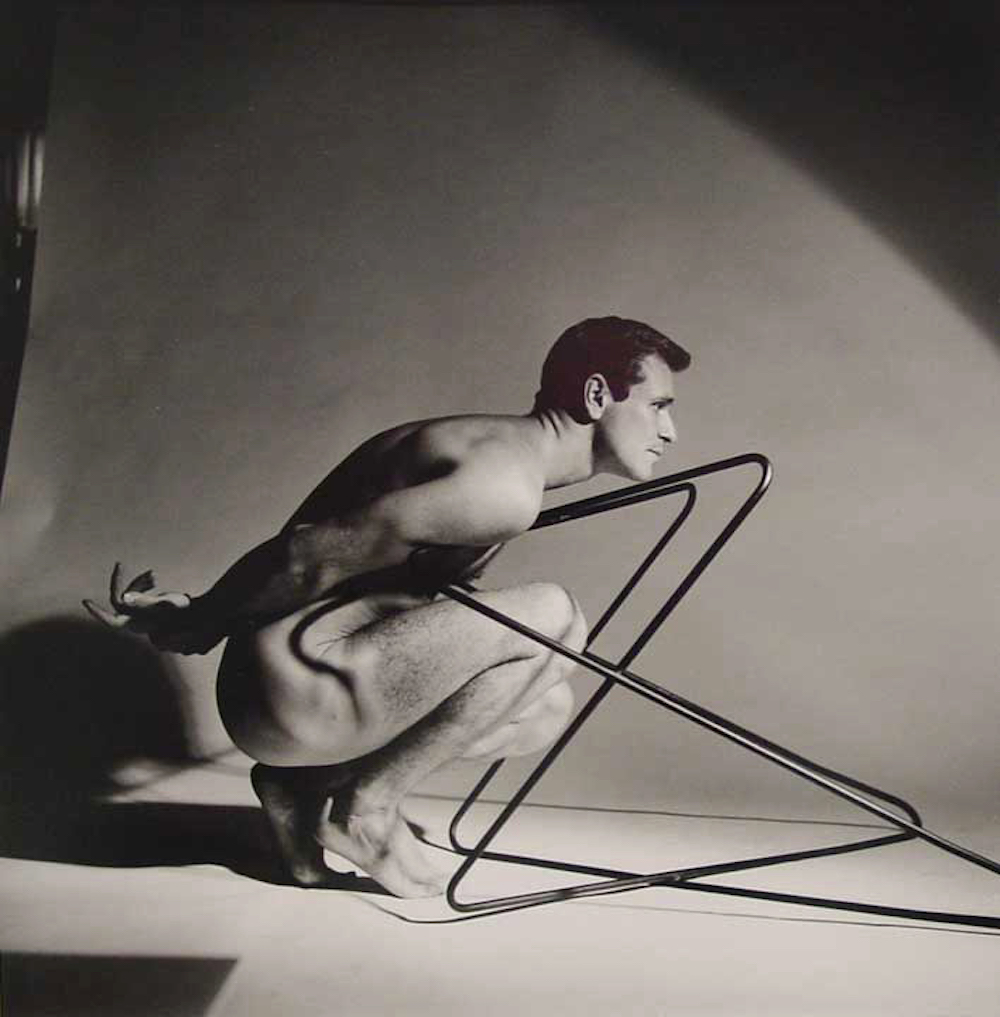

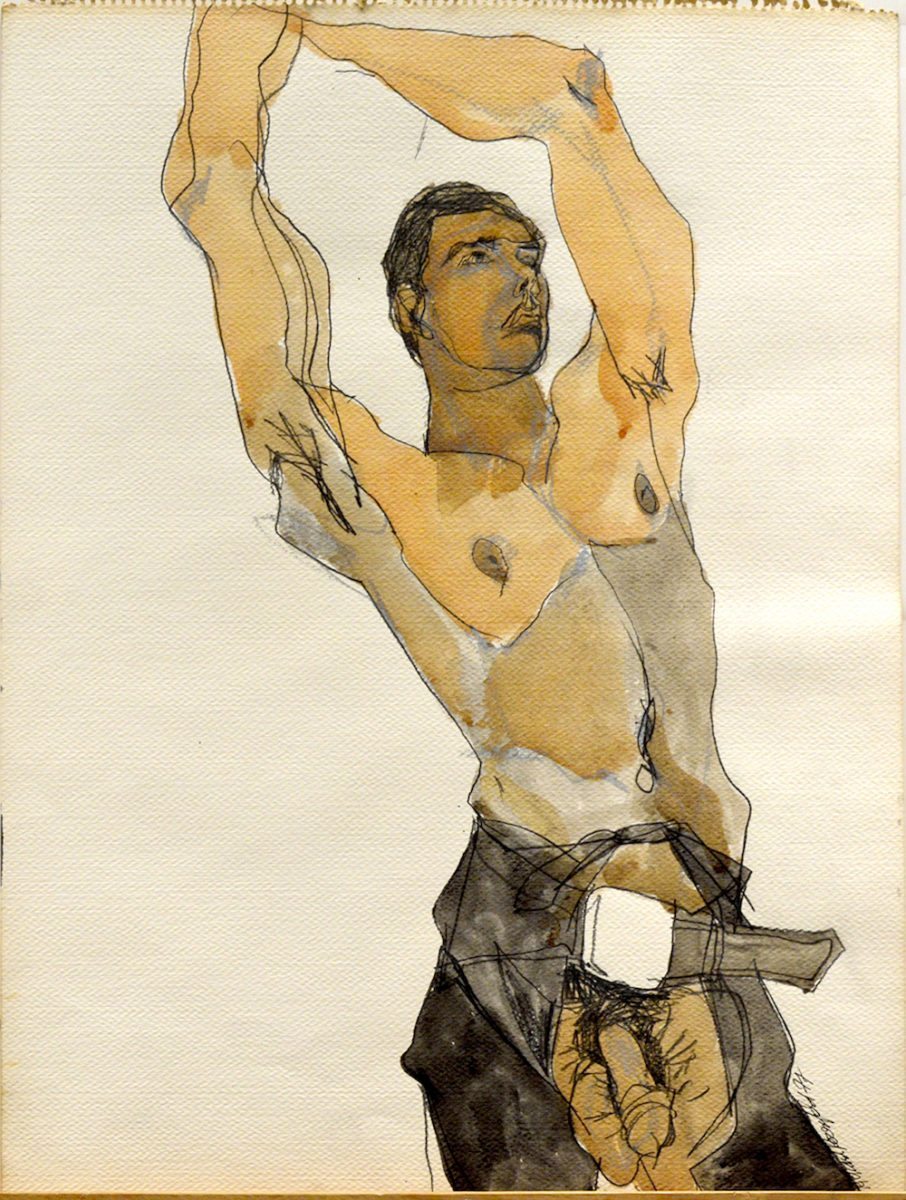

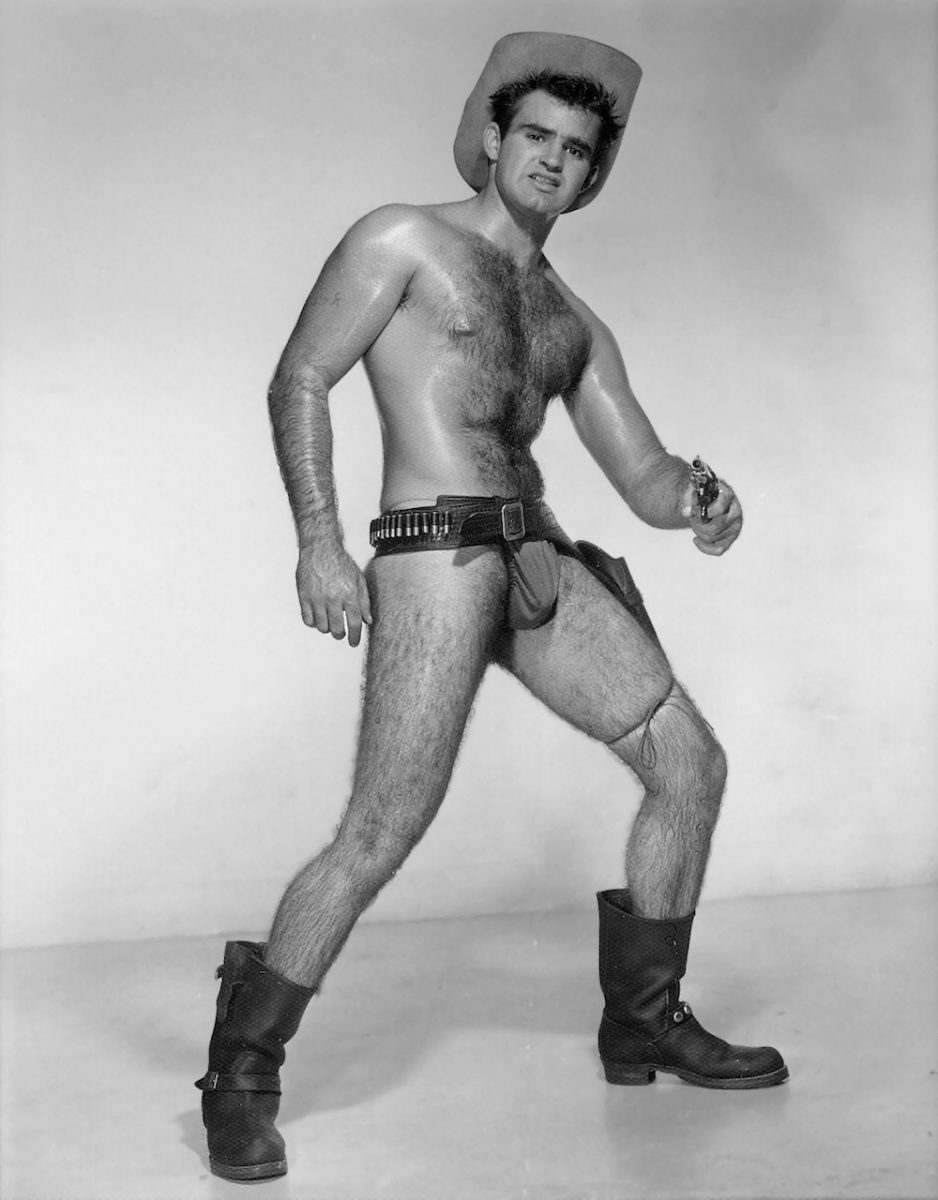

Bob Mizer, a cult figure who had a big influence on both Hockney and Mapplethorpe, is also featured. Mizer photographed thousands of men in the 1940s in his Southern California studio, dubbed the Athletic Model Guild, and is known for his hand in creating that iconic pinnacle of masculinity, the “beefcake”. Tom of Finland is another important figure in the collection, the Finnish artist whose fetish art reconsiders the realms of possibility for fantasy and the male anatomy, while Jean Cocteau’s distinctive homoerotic line drawings, disarmingly evocative in just a few pencil strokes, also feature.

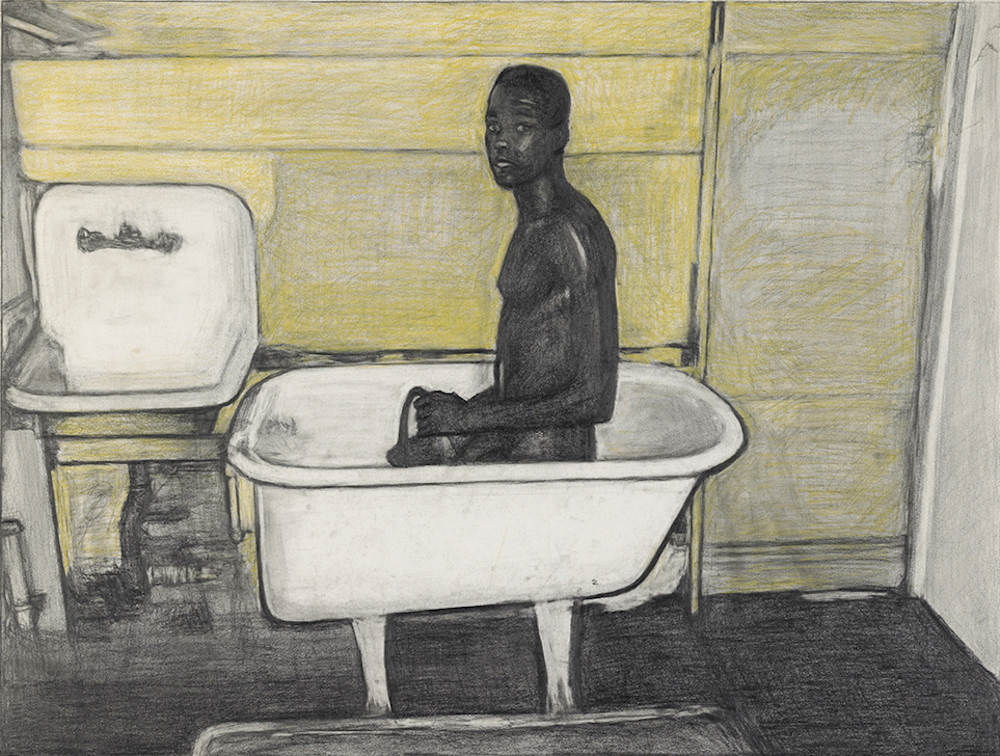

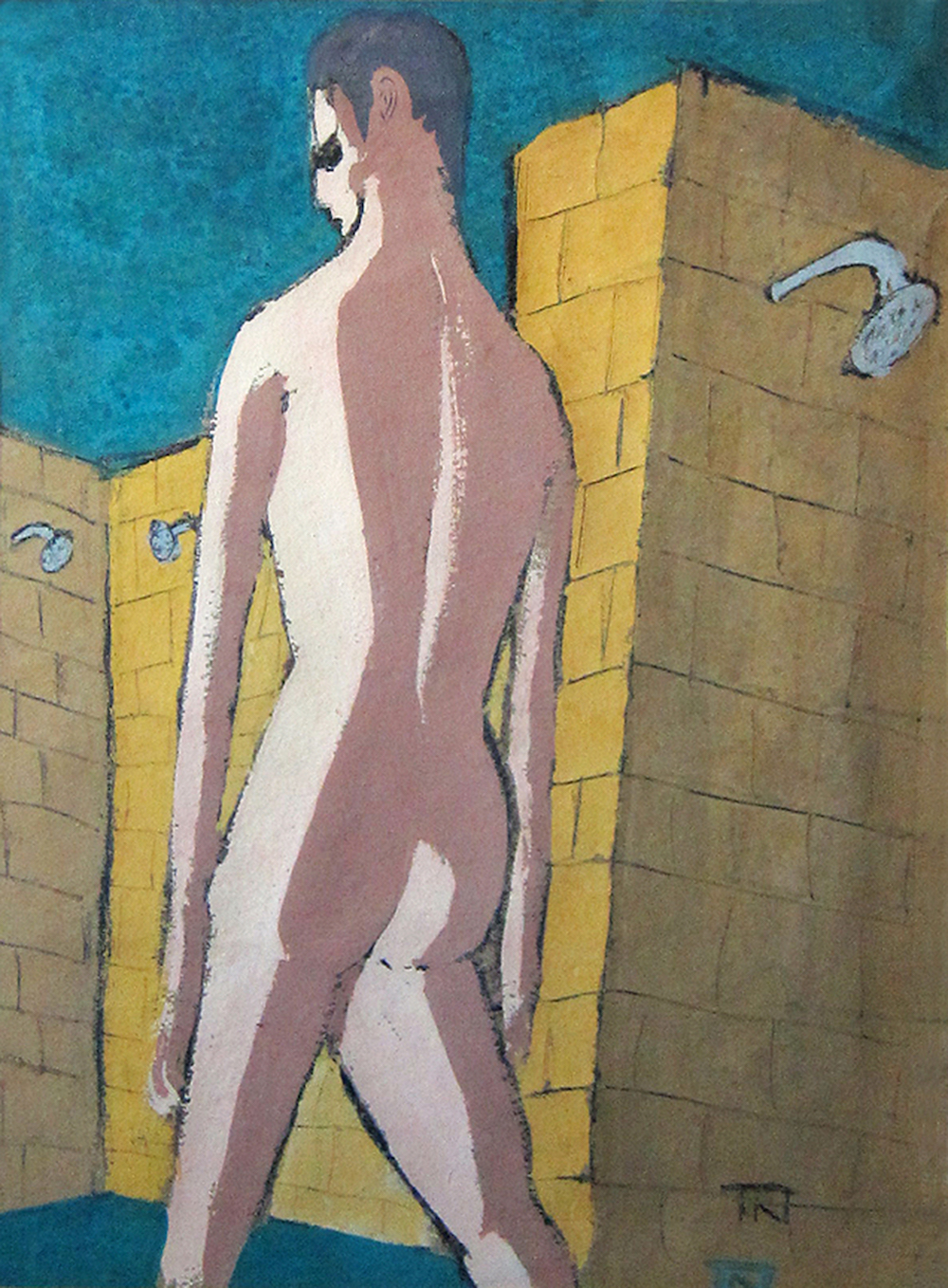

The museum is an important voice redressing the balance of gender, sexuality and difference in a visual arts landscape that remains dominated by a heteronormative point of view. The erotic male form is too often sidelined in this outlook, even as women are undressed again and again to the point of ennui. It is unsurprising therefore that it is in the queer arts that the male body comes to the forefront, when men are able to look at men free from the expectations of the straight gaze. These images are a celebratory archive of queer expression and of the alternative freedoms that can be found in the refusal to conform to the male-female power play.