Each month In The Frame explores the role that art plays on the big screen. From classic noir thrillers to iconic television series, directors have turned to art history and contemporary works to bring their visions to life. This time, it’s the appearance of Poussin’s classical painting of Ovid’s tale of Midas and Bacchus in The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) by German auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Throughout the pandemic, millions around the world found themselves in and out of domestic confinement under lockdown. Few films capture this sense of claustrophobic introspection better than Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972), an all-female chamber drama that never leaves its protagonist’s apartment.

Adapted from one of Fassbinder’s own plays, the all-too-timely conceit centres upon Petra von Kant (Margit Carstensen), an ageing, narcissistic fashion designer locked in a master-slave dynamic with her mute assistant Marlene (Irm Hermann). Petra becomes besotted with the manipulative orphan Karin (Hanna Schygulla), whose treatment of her catalyses the increasingly pathetic older woman’s collapse into self-pitying nihilism.

“Midas and Bacchus looms over the heads of characters, a reflection of Poussin’s Baroque fixation on Classical myth”

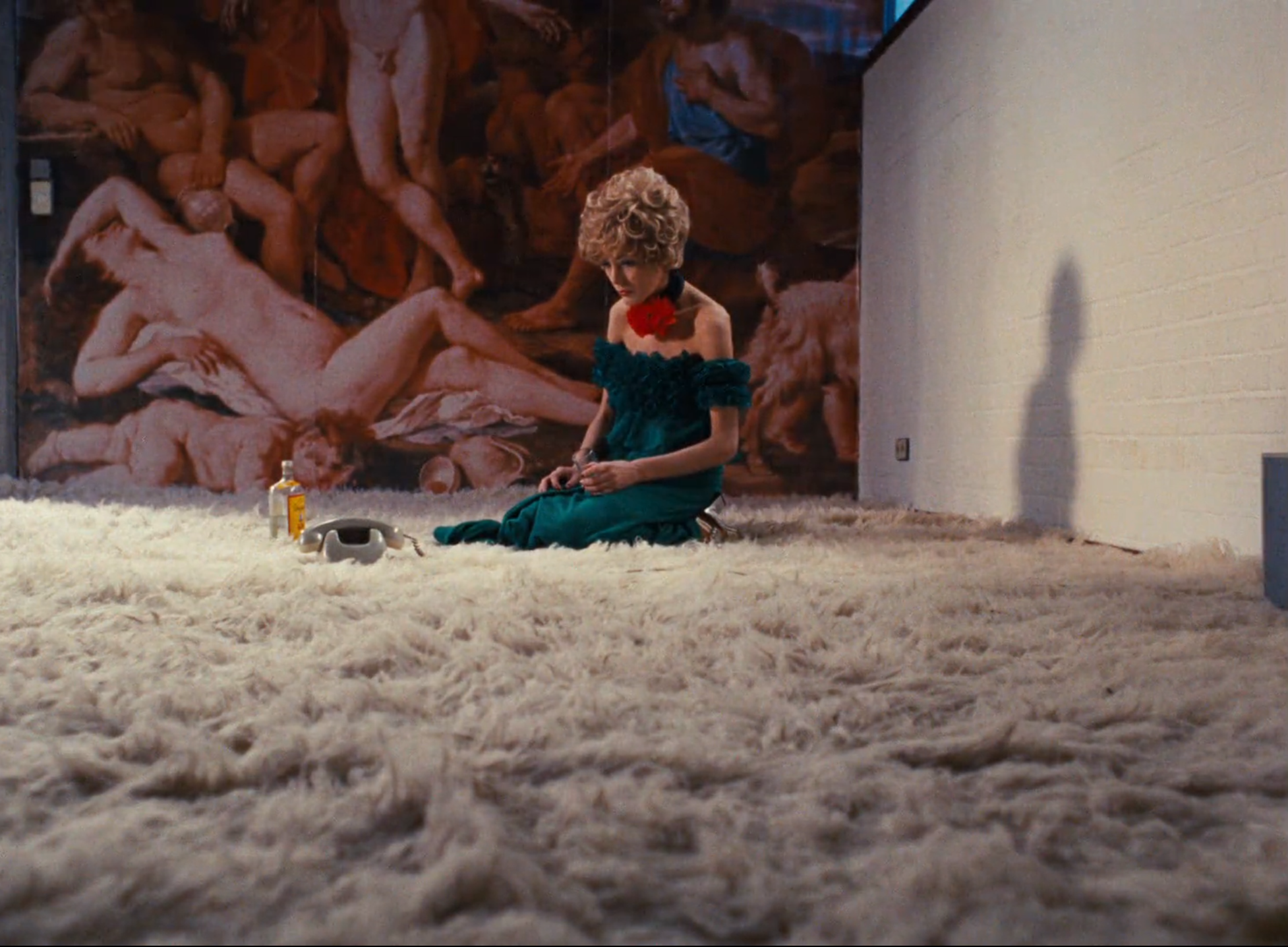

Petra’s apartment (like her wardrobe) is meticulously overdesigned to reflect her decadence and fragility: the luxurious bed she lounges in, the thick white shag carpet. Fassbinder’s camera creeps and drifts through the partitions and peepholes of the space, populated by mannequins that form a silent chorus of disapproval.

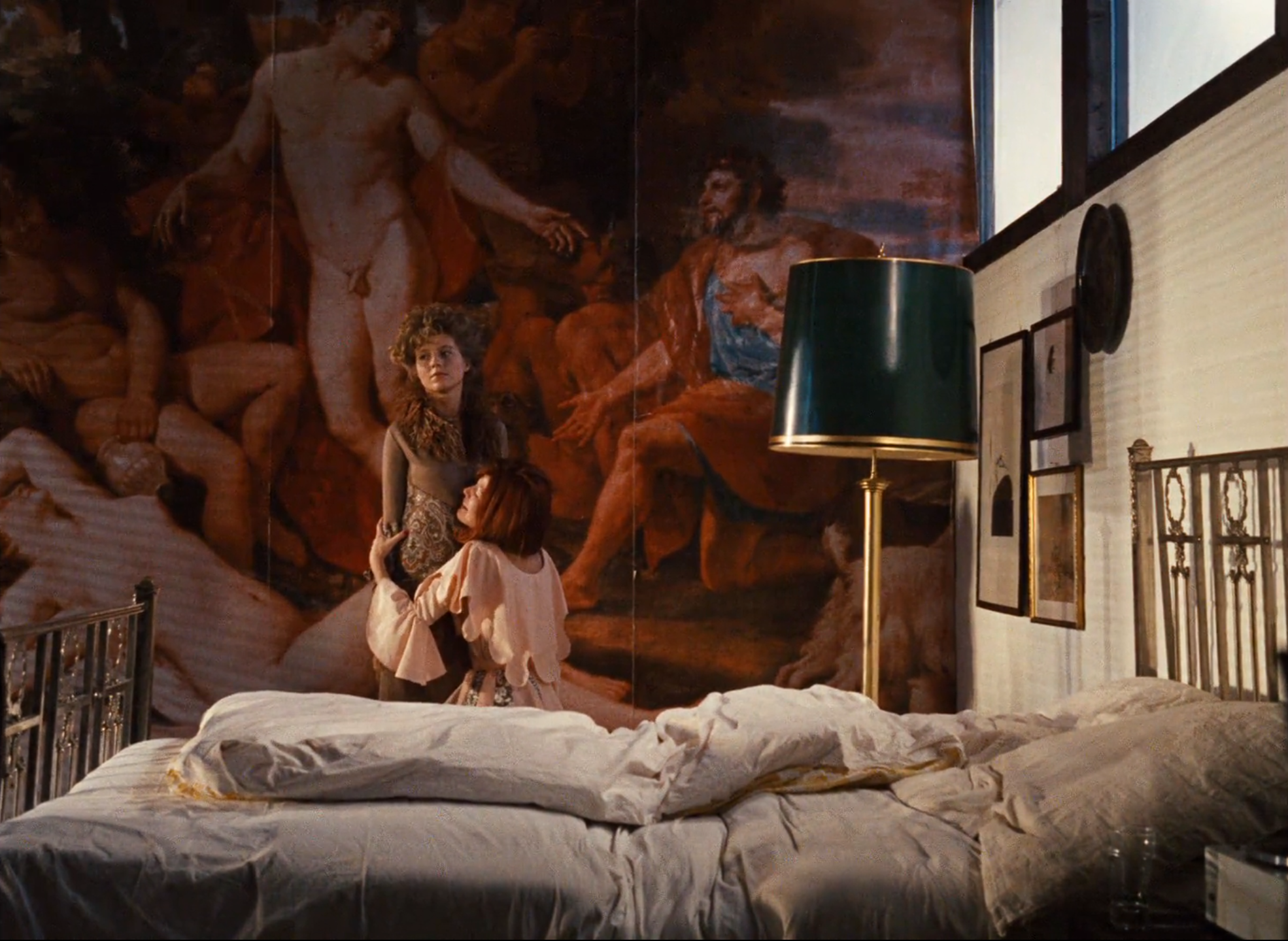

In the centre of Petra’s room, filling the entire wall behind her bed, is a huge blow-up of Nicolas Poussin’s Midas and Bacchus (c 1630) It looms over the heads of characters in almost every shot. The painting, which we never quite glimpse in full, reflects Poussin’s Baroque fixation on Classical myth: the Phrygian King Midas kneels pleading before the naked god Bacchus for the ill-advised power to transform all he touches into gold, while satyrs, cherubs, and naked drunkards sprawl around them.

The sense that Petra is suffocating on her own aesthetic is crucial to Fassbinder’s method. The importance of scenery, lighting and elaborate sets to character development was something he learned from the 1950s Hollywood studio melodramas of the German émigré director Douglas Sirk.

“What can Midas and Bacchus reveal about the psychodrama unfolding beneath it? Might it help us to understand Petra?”

In movies such as All That Heaven Allows (1955), Imitation of Life, (1955) and Magnificent Obsession (1954), Sirk perfected a Technicolor dreamworld vision of post-war America, with outrageously overdesigned sets populated by yearning housewives and taciturn men, and shot through with class and racial tensions. His deployment of vivid, often garish lighting and furnishing to reflect the inner turmoil of his outwardly respectable suburban characters went on to influence the likes of John Waters and David Lynch, and informs the Americana posturing of Lana Del Rey.

Fassbinder, who befriended the older director, said of his mentor’s works: “What passes on the screen isn’t something that I can directly identify with from my own life, because it’s so pure, so unreal. And yet within me, together with my own reality, it becomes a new reality.” What Sirk and Fassbinder shared was an understanding of the subversive potential of melodrama.

A paradoxical genre, melodrama deals simultaneously in repressed emotions and passionate outbursts. Often characters cannot put their deepest feelings into words, which is where things like set dressing comes in. Petra talks a lot, but her words reveal little of herself to Karin. It is her garishly couture outfits, her succession of impractical wigs, her decadently mannered furnishing which speak to her mounting desperation. As film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum had it, Bitter Tears gives us “mise-en-scène as power struggle”.

But what about that Poussin? What can Midas and Bacchus reveal about the psychodrama unfolding beneath it? Is the reference to Midas and his greed a rejoinder to Petra’s decadent, insular lifestyle? A warning, perhaps, of the self-destructive nature of unchecked desire? Or might it reflect some aspect of Petra’s inner life, and even help us to understand her?

There is something uncanny about the way the Poussin is presented which cannot be unseen once it’s been clocked: Fassbinder frames the painting so that Bacchus’s penis is consistently in shot, often dangling almost comically over the heads of the all-female cast. At Bacchus’s feet a naked woman sprawls, an ambiguous figure of both pleasure and subservience.

“Fassbinder frames the painting so that Bacchus’s penis is consistently in shot, often dangling almost comically over the heads of the all-female cast”

Why this almost mocking reminder of male potency in a film populated entirely by women, about a lesbian affair? Men, it appears, are never successfully excluded from the poisonously sapphic world of the film. Petra is a widow, while Karin is married to a man to whom she ultimately returns. Fassbinder himself, meanwhile, drew on his own ruinous infatuation with the actor Günther Kaufmann in writing the relationship between the two women.

For Fassbinder Poussin’s reverie seems to serve as a painful, self-reflective commentary on Petra’s (and his own) failure to live free of patriarchal norms. The painting reveals a failure to move beyond what Sirk might have called an imitation of life, and on to something altogether more real.

Samuel Goff is a writer based in London. A former editor at The Calvert Journal, he focuses on visual culture in the early Soviet Union and the history of cinema

Available to watch on Criterion Collection