“The whole house smells of piss”, my boyfriend astutely observed. Indeed, there is an eau d’urine about the place, as well as the telltale patches left by puddles that don’t seem to quite evaporate from the rugs.

This pregnancy has been quite different from the first. It’s been less about naps and healthy snacks and more passing out on the sofa at 9pm. Yesterday, twenty-eight weeks (or thereabouts) in, I took my first selfie of this pregnancy. It was only to send to a friend, to complain about the fact I feel like a humpback whale and I have pelvic girdle pain. During my first pregnancy, I took my own picture proudly on a daily basis and I felt sexier than I ever had with my flatter, less protruding belly.

Many women have told me that they don’t feel they own their bodies completely during pregnancy, and that this detachment brings with it newfound confidence. Cue a plethora of previously prudish types now willing to pose nude for a camera or paintbrush. A photograph is also a way to mark the beginning of the new life growing, the beginning of a document of a life that still has so much mystery shrouded in the womb.

Pregnant women have, of course, fascinated artists for centuries—as a new exhibition opening this week at the Foundling Museum proves. Over five hundred years of pregnancy portraits are on display, although the first four hundred years are mostly depictions by men. A rare example by a woman comes in a self-portrait painted by Mary Beale in 1660, with her two sons. What Portraying Pregnancy proves is that pregnancy has been, and continues to be, idealized. The adulation of the pregnant form, it’s symmetry, symbolism and its enigma is shown in early examples in the show.

“During my first pregnancy, I took my own picture proudly on a daily basis and I felt sexier than I ever had with my flatter, less protruding belly”

Historically, there was plenty of reason to make pregnancy look pretty: it was useful socially since childbirth was so dangerous that, if the truth were shown, it’s unlikely any woman would have agreed to it. There’s an interesting kind of socio-cultural propaganda that emerges around these portraits of procreativity in seventeenth-century paintings by Hans Holbein II and Marcus Gheeraerts II. The latter’s anonymous “woman in red” stands casually next to her bed, one hand placed gently on her swelling belly—the only confirmation that she is expecting. I dread to think how long the painter must have required her to stand still there, her ankles probably puffy and her back aching.

There’s an exquisite example of a pregnant woman (again, standing) by Thomas Watson, after Joshua Reynolds, dated 1773, of “The Honourable Mrs Parker.” Her whole look is very ancient Grecian chic—no cheaply manufactured maternity wear for women in the eighteenth century—a representation of perfect beauty and femininity.

The problem with these types of images, of course, is that they were so effective they have made us forget that pregnancy—and what comes after—is not always pleasant, nor pleasing to the eye. Even with its aesthetic peaks—breasts and belly inflated, glossy hair and glowing skin—pregnancy is psychologically and physically gruelling. You feel lumpen and heavy, you waddle, you sigh a lot, your nose gets stuffed and you struggle to breathe easily. You get constipation and haemorrhoids, varicose veins and stretch marks. You eat in a way that disgusts people around you.

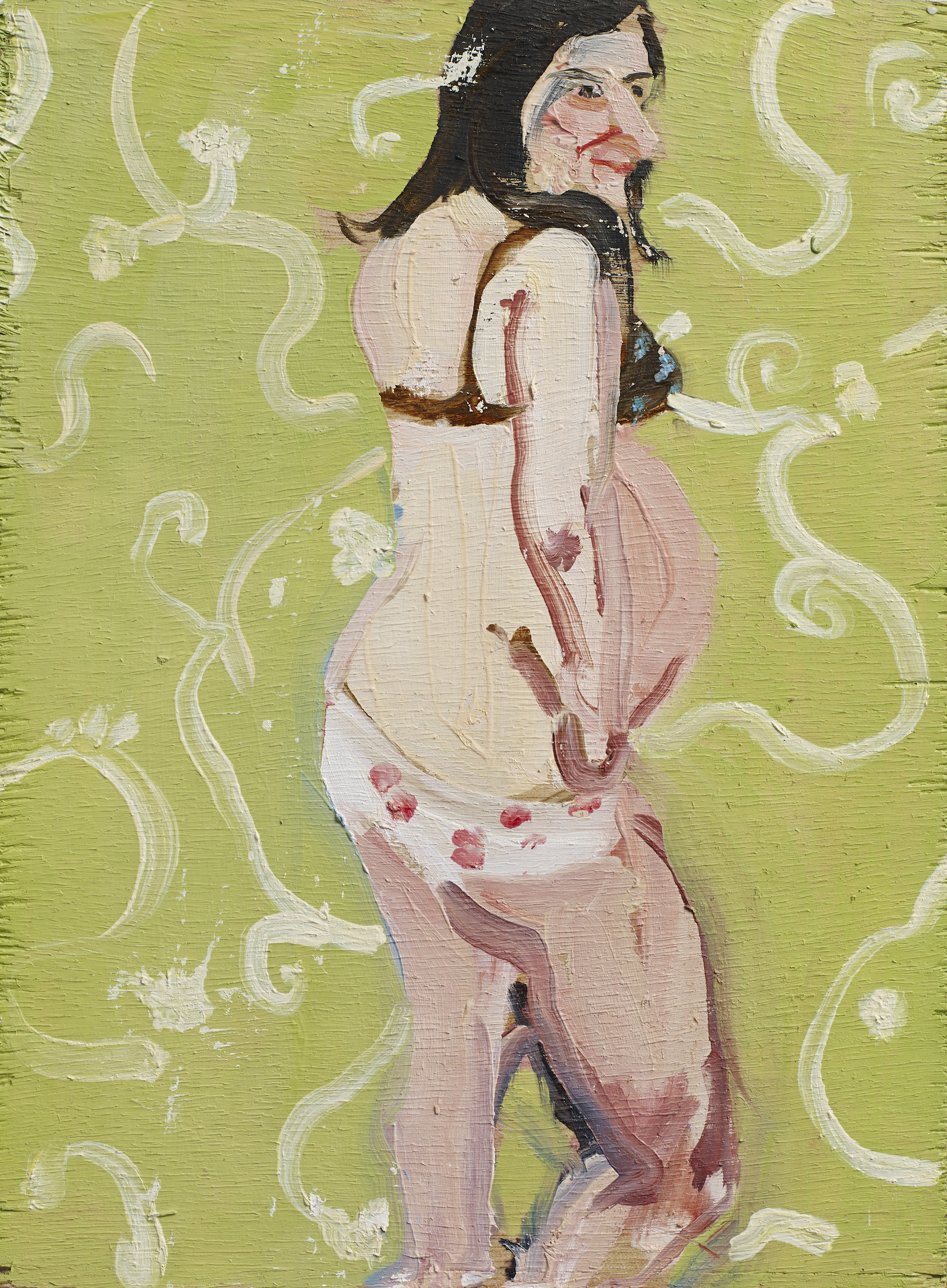

Rolling over in the night becomes an operation; I feel like the mother in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape. For many women, pregnancy is intensely alienating and destabilizing as the body you’ve known for decades morphs out of your control. It’s not a given that you’ll enjoy it. Maybe I am just too hormonal to look at any art, as I’ve felt in a bitter mood for much of this pregnancy, and I feel socially berated for it. Pregnancy is indeed a privilege not to be taken lightly, but it is also a chore. Most art about pregnancy just feels too trite or twee. Give me a Chantal Joffe painting any day.

“Even with its aesthetic peaks—breasts and belly inflated, glossy hair and glowing skin—pregnancy is psychologically and physically gruelling”

What hasn’t been shown, as the exhibition at the Foundling points out, has deeply affected our idea of pregnancy. It has even influenced women’s own responses to their bodies, as much as what has been shown in art and visual culture. In the social media age things are even worse. There are also plenty of examples—think of Awol Erizku’s internet-breaking photograph of Beyonce pregnant with twins. The mythology of pregnancy may have been reclaimed by women, but it continues to be loaded with images of pristine bumps, which appear to be as coveted as the latest IT bag. “Carrying well” is an aspiration as much as “ageing well”, a compliment that actually reveals how unrealistic our ideals are.

The reality of pregnancy remains in many ways a taboo, we self-censor to protect ourselves and others. There’s no doubt pregnancy is something worth celebrating, admiring and cheering ourselves on about, but let’s not pretend it’s a easy either. Feeling cumbersome and tired, I relate the most to a painting by Ghislaine Howard, a pregnant self-portrait in 1984, a sombre mood conjured by muted greys and blues: her slumped, exhausted posture says it all.