Everybody knows a woman on the verge is a moneymaker. In 2007, as Britney Spears buzzed off her locks at a hole-in-the-wall salon in Los Angeles, muttering “I am a good mother,” the salon owner knew she was sitting on a cash cow. “So all that hair was in a pile on the floor, and I tell you, we were all in a frenzy. I grabbed some hair, and she grabbed some hair, and he grabbed some hair and we all ran off to our computers and sell them on eBay!!!” She initially offered it for a million dollars, Britney’s ocean blue Bic lighter and used Red Bull can thrown in to boot. Unable to find a buyer at a million, she offered the locks for sale by the strand, reminding interested parties, “This is a piece of history that cannot be duplicated.”

It is precisely through its reproduction, its virality, that the relic gains value. Lurid images of women mid-breakdown in the mid-2000s often involve a car: Britney midswing, umbrella raised to strike a paparazzi’s Ford Explorer; Lindsay mouth agape, passed out in a grey hoodie, her Mercedes SL-65 on the curb of Sunset Boulevard; Britney sitting in a passenger seat, short skirt, no panties. Girls and cars. Bodies of one sort or another.

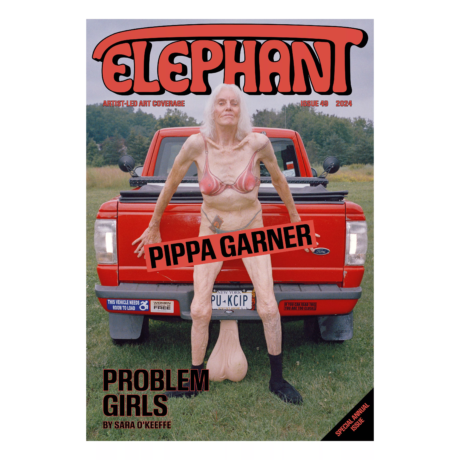

Artist Pippa Garner has an affinity for both. A quintessential American artist (although she likes to joke that “part of me is European” since her vaginoplasty was in Belgium), Garner even has red, white, and blue permanently emblazoned on her flesh: a tattooed red and white bra (“even if I gain 300 pounds, it will still fit”) and a tattooed blue G-string, crotch pushed aside ready for action, waistband stuffed with $5,000 of inked Monopoly money (“I’m no longer allowed to go to nudist colonies!”). Garner has made a career out of body modification—altering her own, and the all-metal variety found in the auto body shop. At age 81, she’s finally having a comeback, serving as an icon for a new generation of artists, writers, and fashion designers hungry for her style of deadpan conceptualism and hardcore commitment to the gag.

A self-proclaimed “senior slut,” Garner’s work—irreverent and defiantly unclassifiable—may just be the medicine we need. For more than five decades, she has embedded her projects in the world, often realizing work outside the confines of galleries, museums, or the boundaries of what has been strictly defined as art. Now, the art world is finally embracing her: she is included in the Whitney Biennial, her newest conceptual car Haulin’ Ass! (2023)—a cherry-red Ford Ranger removed from the chassis, exterior flipped 180 degrees and welded back together, outfitted with super-sized truck nutz (with a “z”™!)—has been joy riding across New York and LA. This set of wheels was commissioned by Art Omi, for her first institutional solo show in New York $ELL YOUR $ELF, accompanied by a monograph of the same name, a Garner bible of sorts that I edited, co-published by Art Omi and Pioneer Works Press. On the back (now front) of Garner’s flipped pickup truck, a bumper sticker proclaims “Women should be free (No charge!).” It is this slippage from liberation to commodity (and back again) that Garner’s work circles. The best advertisers are in the business of selling problems. Garner’s work—in all its macgyvered-together glory—teases at the problems and delicious mess lurking under the shiny optimism of the sales pitch.

Garner grew up in the Midwest, born in Evanstown, a small town just outside of Chicago. Her father was a McCall’s ad man. As a child, he would take Garner on tours of the print shops, a factory teeming with long spools of newsprint stamped with images of smiling women and all the shiny goods for sale. Most issues featured a page with a paper doll and the latest fashions, just waiting to be cut out. The family moved frequently for her father’s work; in high school, Garner took life drawing classes at the Cleveland Institute of Art before moving to California to study automotive design at the ArtCenter with dreams of becoming a car stylist.

After returning from the Vietnam War (Garner was drafted and forced to serve), Garner’s cars took a visceral turn: they morphed into fleshy things with veins and orifices. She drew them with warts and gashes. They breathed. One bears a giant slit in the passenger door, which a dog gingerly licks. In a gesture begging for Freudian analysis, Garner labels this the car’s “wound.”

During her senior year, on the brink of graduating, Garner produced a Cronenbergian prototype: metal turned flesh, a work titled Kar-Mann (Half Human, Half Car) (1969). Taking a children’s pedal-powered vehicle, a miniature of the popular sixties Volkswagen Karmann Ghia model, Garner sliced it in half. The rear morphs into a hand-sculpted human body, one leg raised, taking a piss like a dog. Garner paraded the work through the school’s halls. Beneath Kar-Mann lay a map of Detroit, headquarters of the Big Three—General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler—behemoths of American car manufacturing. These plants not only redefined the conditions of American labor, but were key in military manufacturing, producing many of the weapons Garner had encountered in Vietnam. Garner’s car took a piss on them all. She was expelled.

Her interest in hybrid mechanical bodies started early, through military technology. As a child, she saw new Air Force gear being tested in the skies, monstrous forms with altered bodies:

I remember fighter planes circling overhead from nearby Great Lakes Naval Base. I also glimpsed an experimental flying wing bomber going overhead, a surrealistic and sinister vision to me, which became the central image in a recurring nightmare that bothered me for years. The wing, all black, is circling overhead looking for me. I am crouched, half hidden but feeling very vulnerable, behind a drudge, peering through tall weeds into a barren valley. The huge plane eventually lands in the clearing and comes to a rest. I am momentarily relieved, but soon a hatch opens in the plane’s belly and out flies a small silver airplane to begin the search all over again. I am frozen in terror. Just as the plane spots me I wake up. (From an unpublished typewritten page in Garner’s archive, dated January 1992.)

In Garner’s work, flesh and metal—or flesh and silicone or flesh and wood—are often juxtaposed, and in many cases, fuse. They become prosthetics but also barriers, exoskeletons that hide the body from prying eyes and protect from injury. Long before a generation of artists began plumbing surveillance and visibility in the post-internet age, Garner proposed devices to obscure one’s image, tools for hiding in plain sight.

Despite the bombastic nature of Garner’s stunts, her works often disappear in documentation, camouflaging themselves in the routine of daily life. Make no mistake, Garner’s affinity is for the banal, firmly placed in the muck and bric-a-brac of this cheap, dirty world. Her work offers deviant solutions to everyday problems, addressing the anxieties and pressures that course through the office and the home. Embedding her work in traffic, business wear, television, newspapers, mail order catalogs, her mission, she wrote on a 1990 course syllabus at the Otis College of Art and Design and the task she was setting forth for her students, was to “look for ways to find inspiration and stimulation in seemingly ordinary situations. The enemy is boredom and the tendency to slip into ‘system-think’…we must be able to dramatize the mundane.” Directly addressing the anxiety, alienation, and paranoia that course through the office and home, Garner would propose thousands of devices to deflect, subvert, or retool the mounting pressures of productivity and visibility today.

In 1973, just a few years after her expulsion from the ArtCenter, Garner conceived of her first major conceptual car, Backwards Car, a 1959 Chevy with its exterior rotated 180 degrees so it appeared to face the wrong way as it drove. Esquire fronted her the money to produce the piece on the condition that it run as a feature in their magazine. In a gesture at once daredevil stunt and conceptual probe, Garner scaled San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge in the work. She was finessing an important principle: how to follow the letter of the law while utterly defying it in spirit. Later asked about the piece in an interview with the editor of Car & Driver Magazine, Garner remarked, “I could have caused a fifty-car pileup without breaking the law. Terrorism meets art.” ( John Philips, “The Original Crossover,” Car and Driver Magazine, May 2015, 30.)

Garner was not alone: her friends and collaborators during this period—including artists Ed Ruscha, Chris Burden, and the collective Ant Farm—used the automobile to interrogate the language of American commerce, machismo, and the slippery boundaries separating art and life. Burden crucified himself atop a Volkswagen Beetle in Trans-Fixed (1974), the same year that Garner scaled the Golden Gate Bridge. Ruscha used the car as an apparatus, camera mounted to it as he cruised down Sunset Strip (1966) and the Pacific Coast Highway (1974). For Garner too, the car was not only a device, but also a means to an end: a devotee of Rube Goldberg (even penning an introduction to a catalogue of his machines), Garner understands her contraptions as devices to tickle something loose in the minds of onlookers, which holds the potential to set into motion a series of radical chain reactions. An anarchistic bent hums just under the surface of the work. In unrealised proposals from the 1970s, she argues for riots and art terrorist groups to form, a response to “combined pressures of inflation, [and] media overkill” in LA.

Garner’s vast output is astounding, and she is long overdue for a retrospective that brings together her works across disciplines, which are today scattered around the United States (although at the time of this writing, woefully underrepresented in museum collections). More research is needed into her oil paintings from the 1960s, her sculptures, drawings, photographs, garments, vehicles, and performances produced between the 1970s to the present. No show to date has brought them all together.

Art museums have been particularly slow to embrace the work, in part perhaps because Garner has been ambivalent about classifying what she does as art. Unsurprisingly, she has refused to conform to the rules that bind a good career artist (she religiously delivers on deadlines, but you’ll rarely find her rubbing shoulders at exhibition openings these days). Never faithful to the white box, Garner’s work is promiscuous: it’s in the back pages of weeklies and trade magazines, embedded in trans advice newsletters and VHS tapes, roaming the streets. More interested in strategies of infiltration, in entering the gutters of culture than occupying those clean four-cornered walls of institutions, perhaps it’s no surprise institutions ignored it for decades.

Garner’s works nevertheless wink at art history: Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, F. T. Marinetti. In her artist books disguised as mail order product catalogs (Primary Information just issued a facsimile of her 1982 cult classic Better Living Catalog last year) lurk citations of other artists’ works: examine them closely and you’ll find a small photograph of Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel slipped in beside a dresser. Tucked behind a dining room table in another scene with Garner’s prototype is an Ed Ruscha: red, white, and blue behind the crisp white phrase, “PROBLEM” GIRLS—the word “problem” in quotation marks. What is a problem anyway?

The word problem has its roots in Greek: pro- (moving forward) and ballein (to throw), a problem has propulsion to it; it is a thing set forward in motion. In Garner’s world, nothing is fixed: products, social codes, common turns of phrase are always being scrapped for parts and reassembled. She relishes a break from the script, deviations so slight that upon first glance they may be missed. Look again and the whole picture starts to run amok.

By the mid-80s, Garner had started toying with the idea of gender hacking—a process that she considers a conceptual artwork—marking an extension of her practice from twenty years of altering cars, garments, and consumer products to using her own body as raw material. Doctors refused to grant her access to hormones unless she adhered to a narrow script (and never one to play to another’s tune), in 1986, Garner opted to go the black market route, tinkering with her dosages until she found the right combination of estrogen and testosterone to make her feel comfortable, alert.

Always a gig worker, piecing together funds here and there from miscellaneous jobs, Garner didn’t have the money for breast implants until she remembered that Ruscha and she had traded artworks. When her Ruscha lithograph Mr. Ray (1975) was appraised, it was worth exactly the amount she needed for the operation, a sign. “Two for one,” she told me: two of her favorite artists are now figuratively connected to her. Reflecting on Ruscha’s trade, she told me, “It was an artist helping other artists… I should have him tattoo sign them.”

Embracing her own objectification, Garner became serious about tattoos while living in Santa Fe in the 2000s. She had given up driving gas-powered vehicles at this point, opting instead for “human-powered vehicles,” bicycles or pedal cars that she fabricated. After her bike was hit by a car, her leg wasn’t the same; it appeared stiff, not her own. Garner decided to run with the idea, and cover her leg with woodgrain (American oak), a nod to Magritte’s 1926 painting Discovery, in which a woman’s skin erupts into patches of woodgrain—a subject morphing into object. Garner enlisted the services of tattoo artist Dawn Purnell Furlong for the work, and enjoyed the collaboration so much that she partnered with Purnell Furlong on three more of what she deems her series of trompe l’œil tattoos: a bra, G-string, and later, post-it note with the handwritten phrase, “I is a ass.”

It is no surprise that two of the “Holy Trinity” of the 2000s (problem girls no doubt), Britney Spears and Lindsay Lohan, appear in Garner’s drawings from this period, depicted in—what else—but cars. Cannibalising pop cultural references, images of her own mass media appearances, and phrases from advertising, Garner collages these forms together in new incarnations, often produced in long drafting sessions with graphite while on MDMA. In Garner’s formulation, Lindsay Lohan has sprouted a new appendage, a giant boil erupting from her forehead, protecting her from damage in a car accident. A useful implant.

As Garner’s vision has declined (today she is legally blind), she has maintained a practice of producing a T-shirt a day, using iron-on letters and often sourcing vintage shirts on eBay to tinker with popular phrases in ways that reclaim their lusty potential and thumb her nose at assimilationist narratives. Think On Kawara’s date paintings, but smuttier. Some read, “Rectal Linear,” “Hetro Shame Weekend,” “I could be your Grandmother, isn’t that kinky?” Some point to the conditions of her body (“I was on life support, but I got away”) others to labor and class (“I pay my stalker a living wage,” and “I smell money! Is it you?”)

These days, Garner has no lack of ideas for new works, she is only up against the limits of her own body, the toy that has served her well, now in a battle with leukemia. Even her death is an opportunity for a final artwork: her tattoos should be preserved and placed on view at the Horiyoshi III Tattoo Museum in Japan. The meat from her body should be eaten. If possible, her T&A (Garner’s shorthand for tit and ass implants) should be “extracted, signed, and put back in [the cadaver]; added to the archive post-humorously.”

While a teenager in Cleveland Heights, Garner would crawl into the sewer system and spend hours exploring the vast network of tunnels and chambers buried deep underground, the bowels of civilization. There were different rules there. Every now and then, she would force a manhole open and ask a bewildered passerby where she was, only to submerge again. Isn’t it more fun, she reminds us, to dispense with decorum and revel in the trash?

Written by Sara O’Keeffe