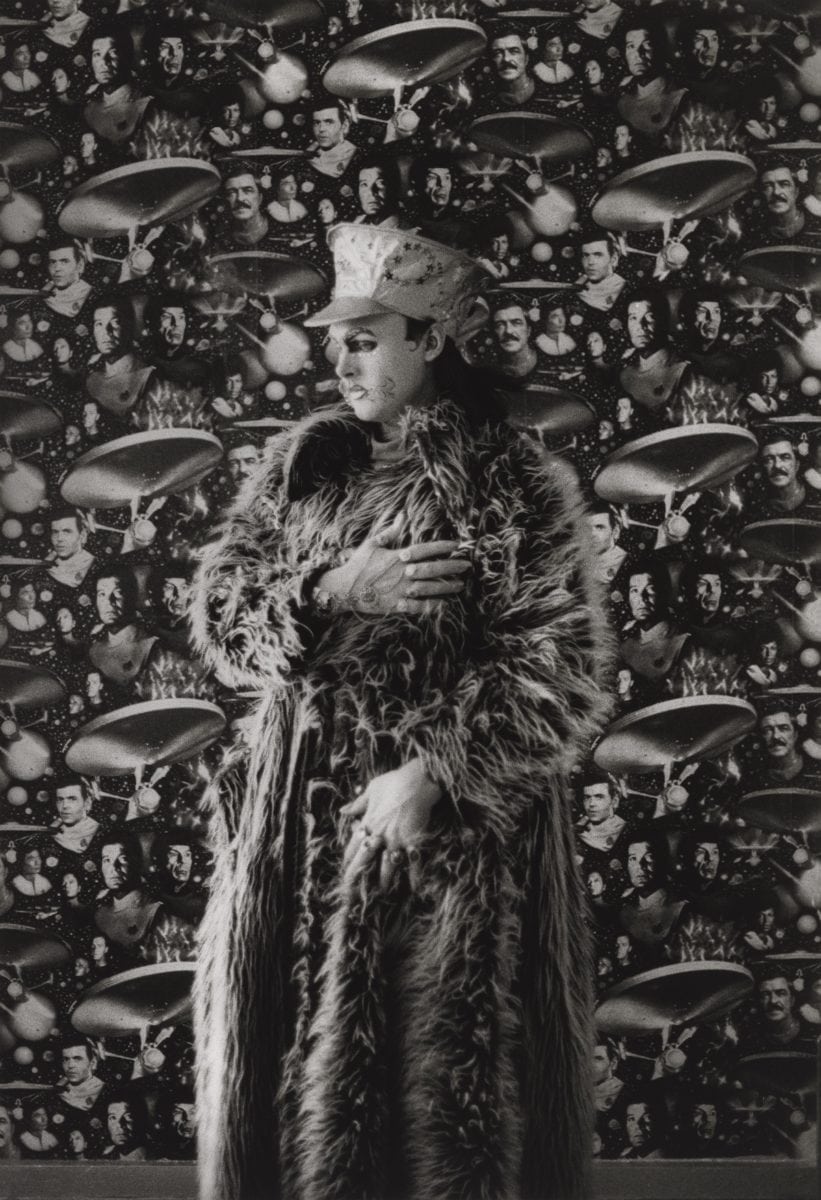

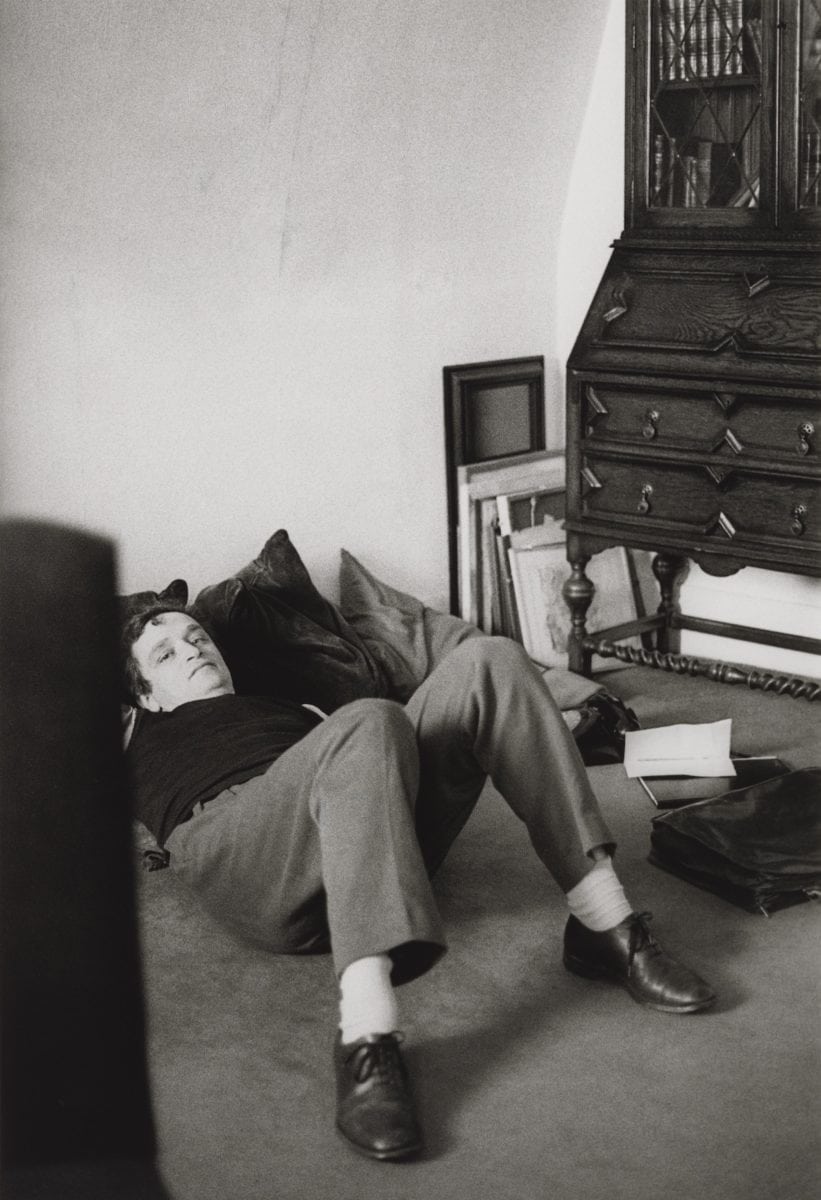

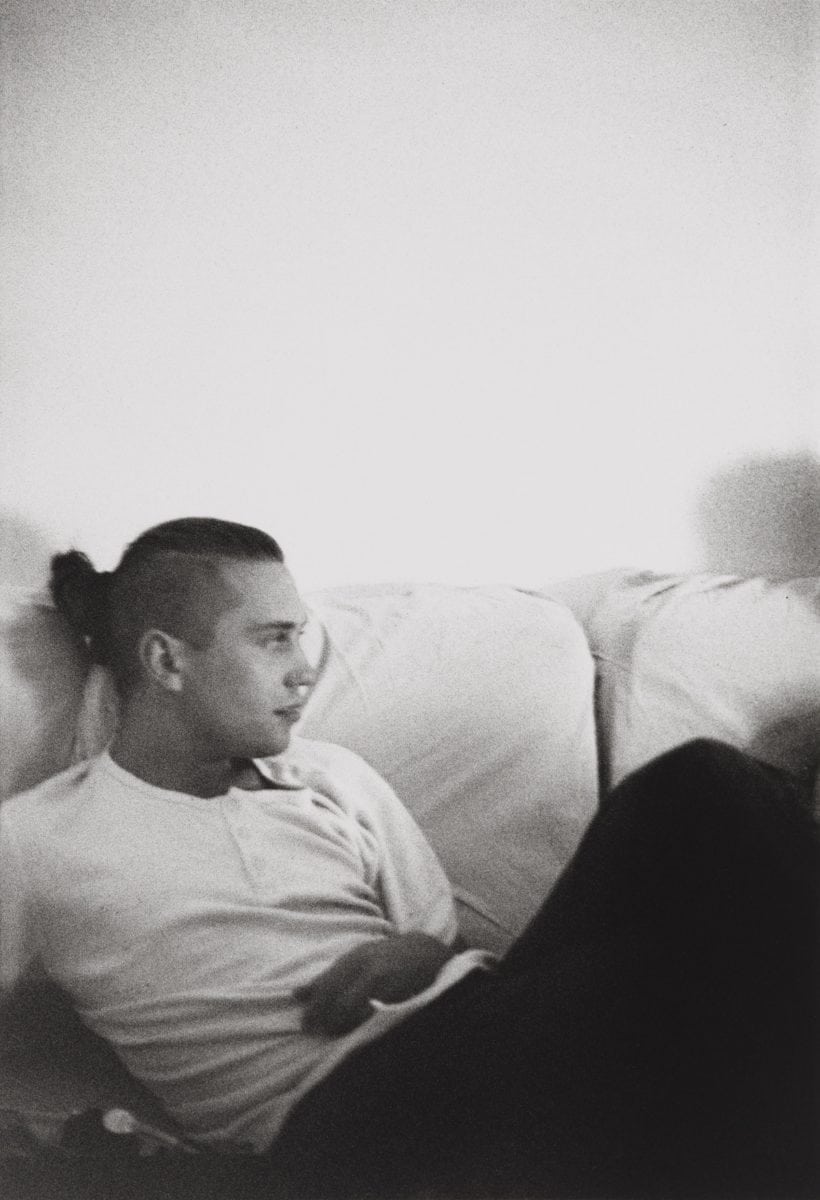

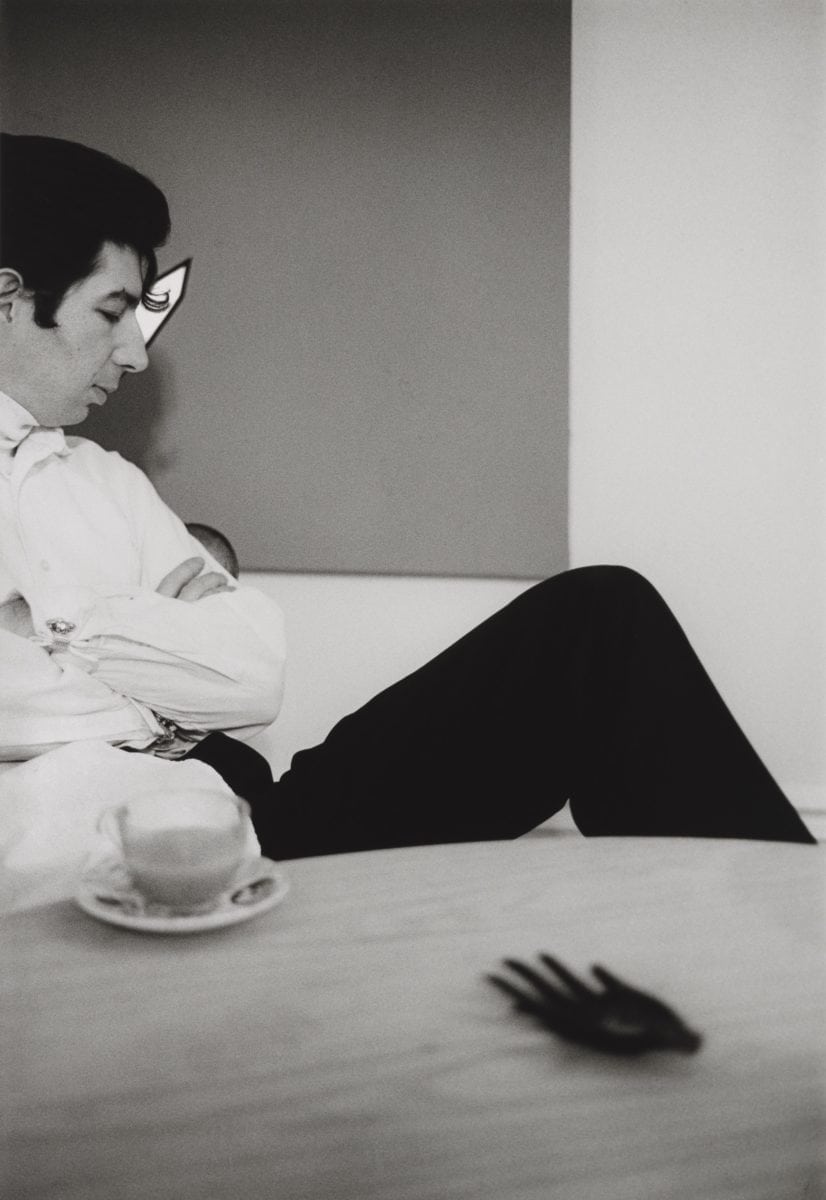

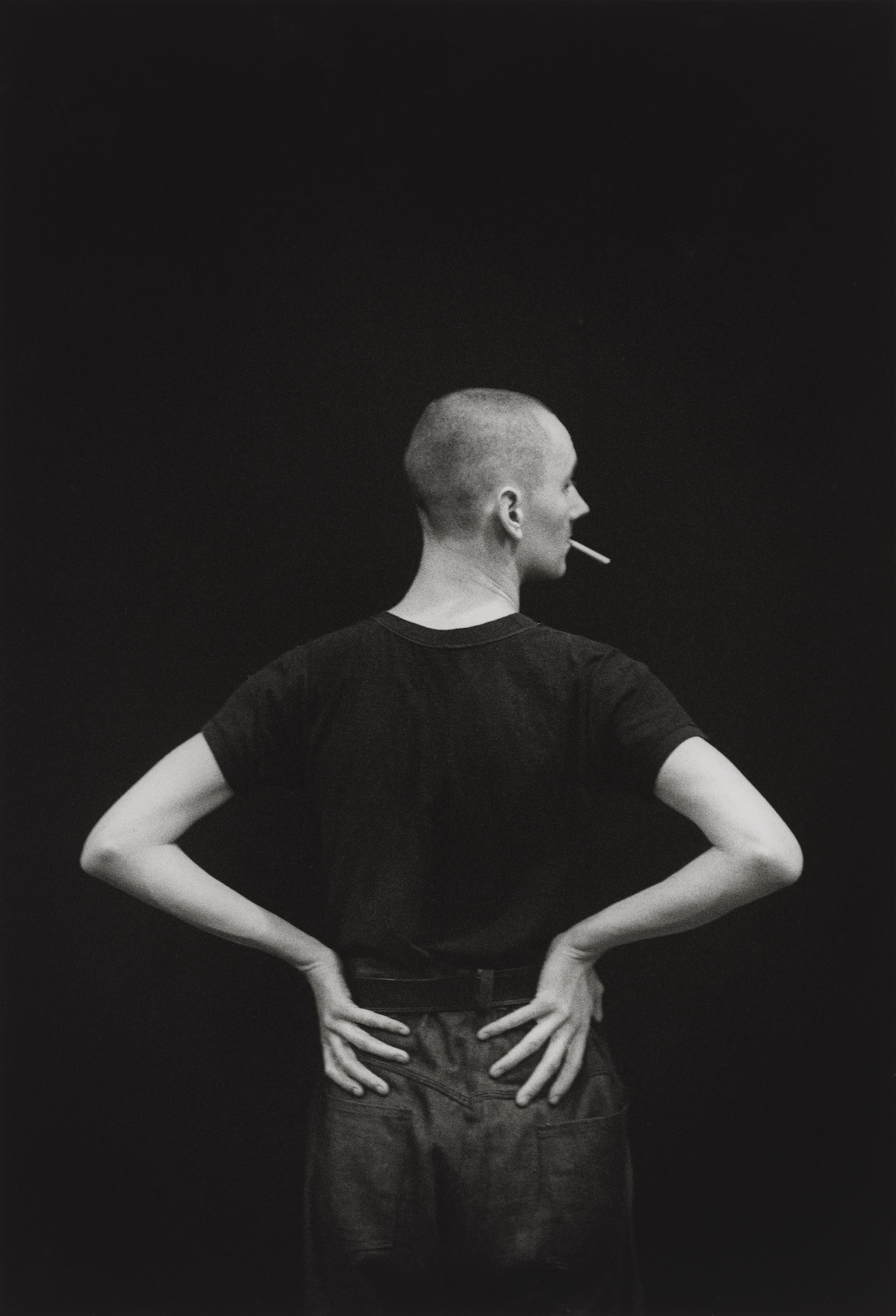

Photography has the powerful ability to build nostalgia for a time and place—even if you were never there at all. The handheld camera in particular allows for unguarded, intimate shots, and the resulting images can create the uncanny illusion of proximity years after the fact. The men who lounge on crumpled sofas and languidly lean against a front door in the pages of David Gwinnutt’s deeply personal photobook feel as if they could be your friends, chatting for hours into the soft early morning light or arguing sleepily at the day’s end. These are images that take on the casual air of relaxed familiarity, made all the more remarkable for the famous faces that they contain. Derek Jarman, John Maybury, Cerith Wyn Evans, Leigh Bowery, Gilbert & George, Duggie Fields… the cast of The White Camera Diaries brood and fret in grainy black and white, straight from the heart of 1980s queer London.

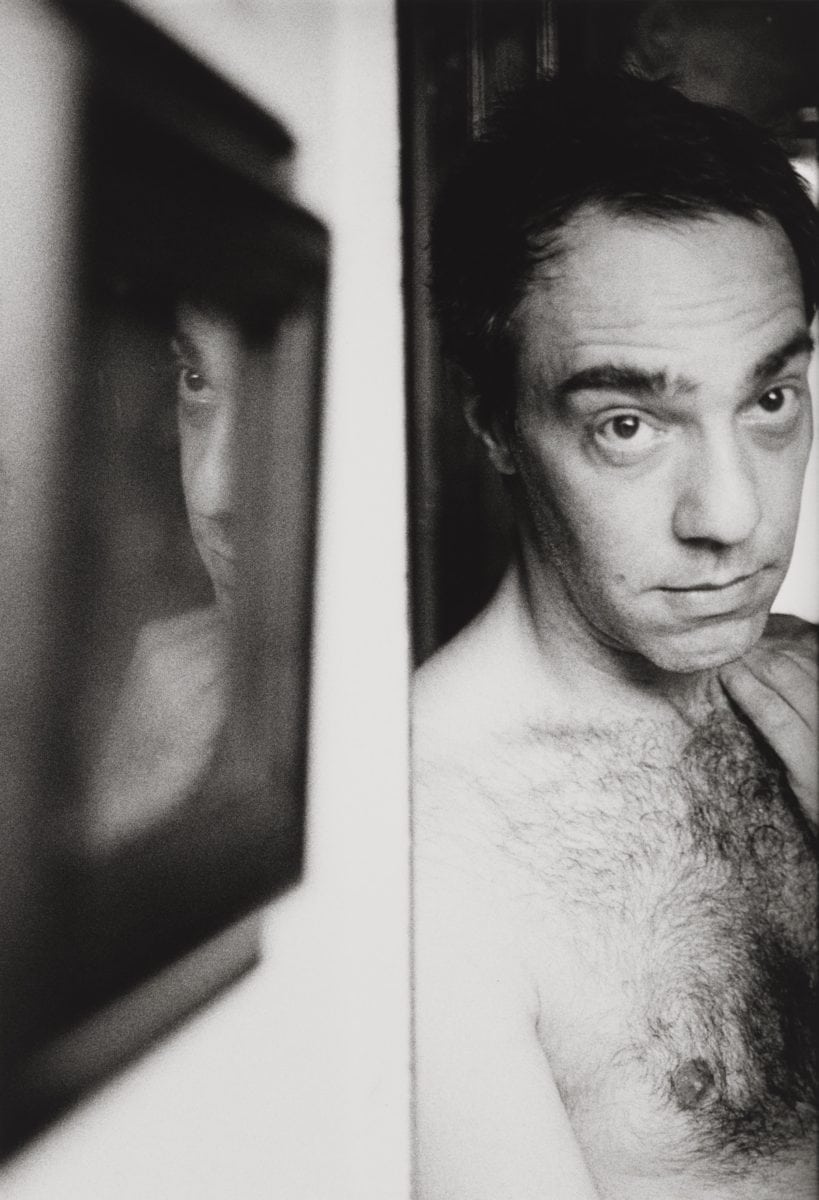

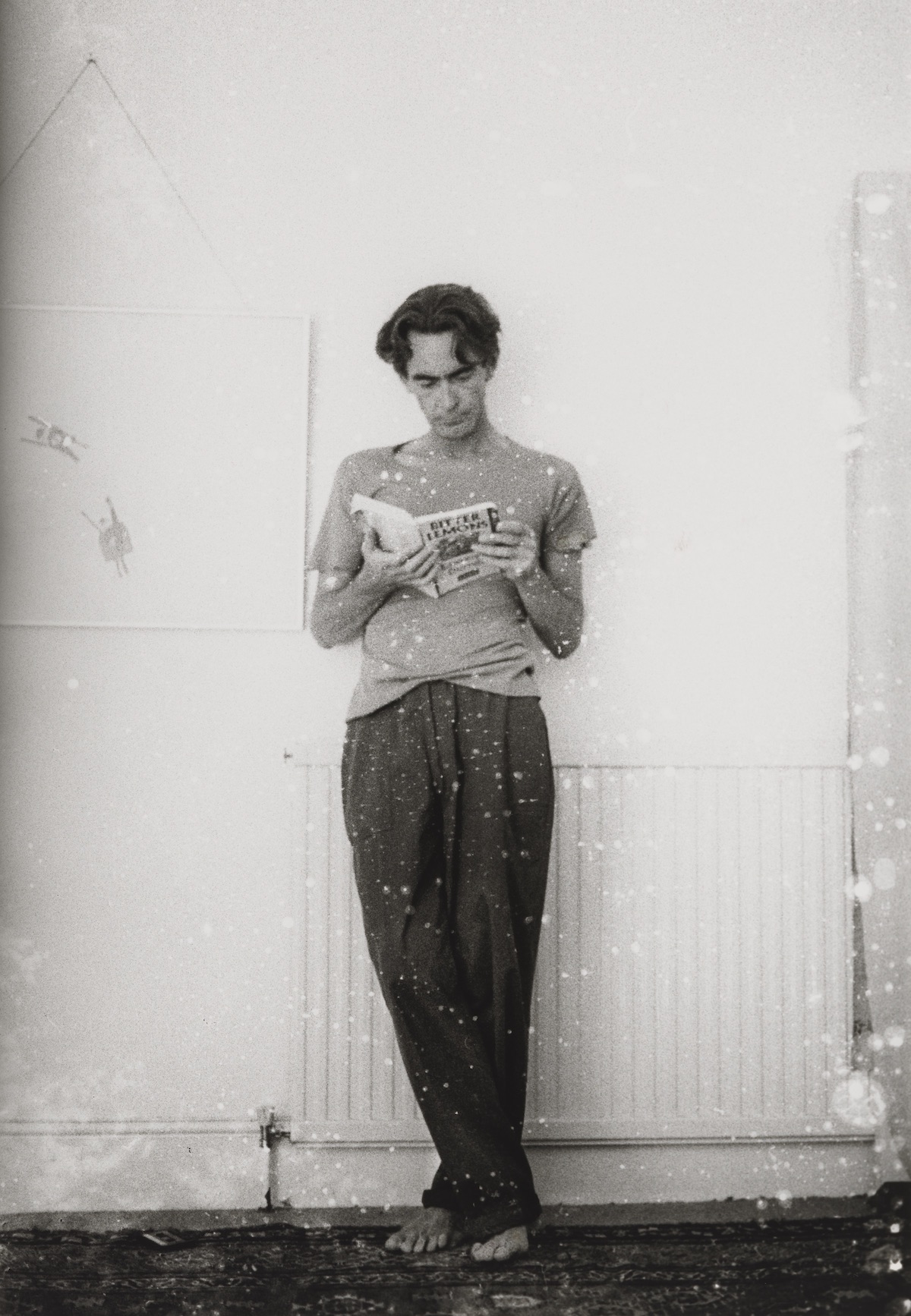

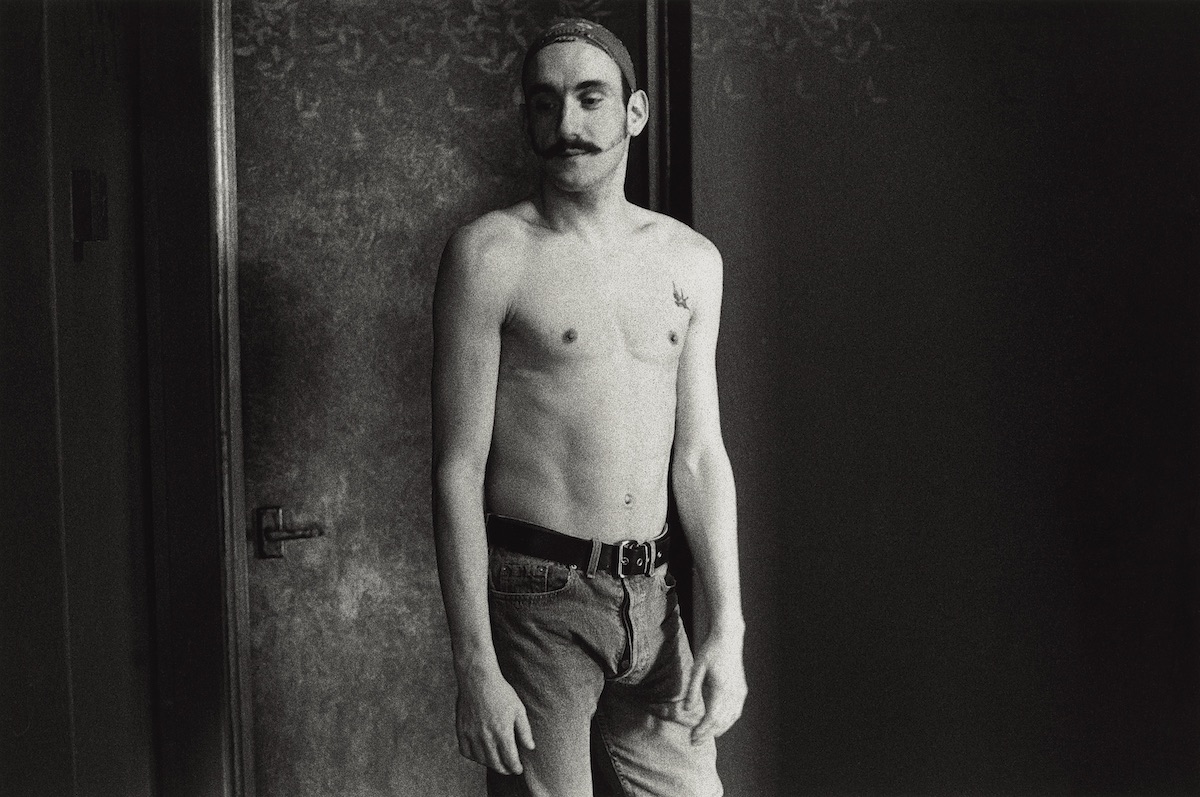

- Left: Leigh Bowery, circa 1983; Right: Sir Norman Rosenthal, 1983-1983

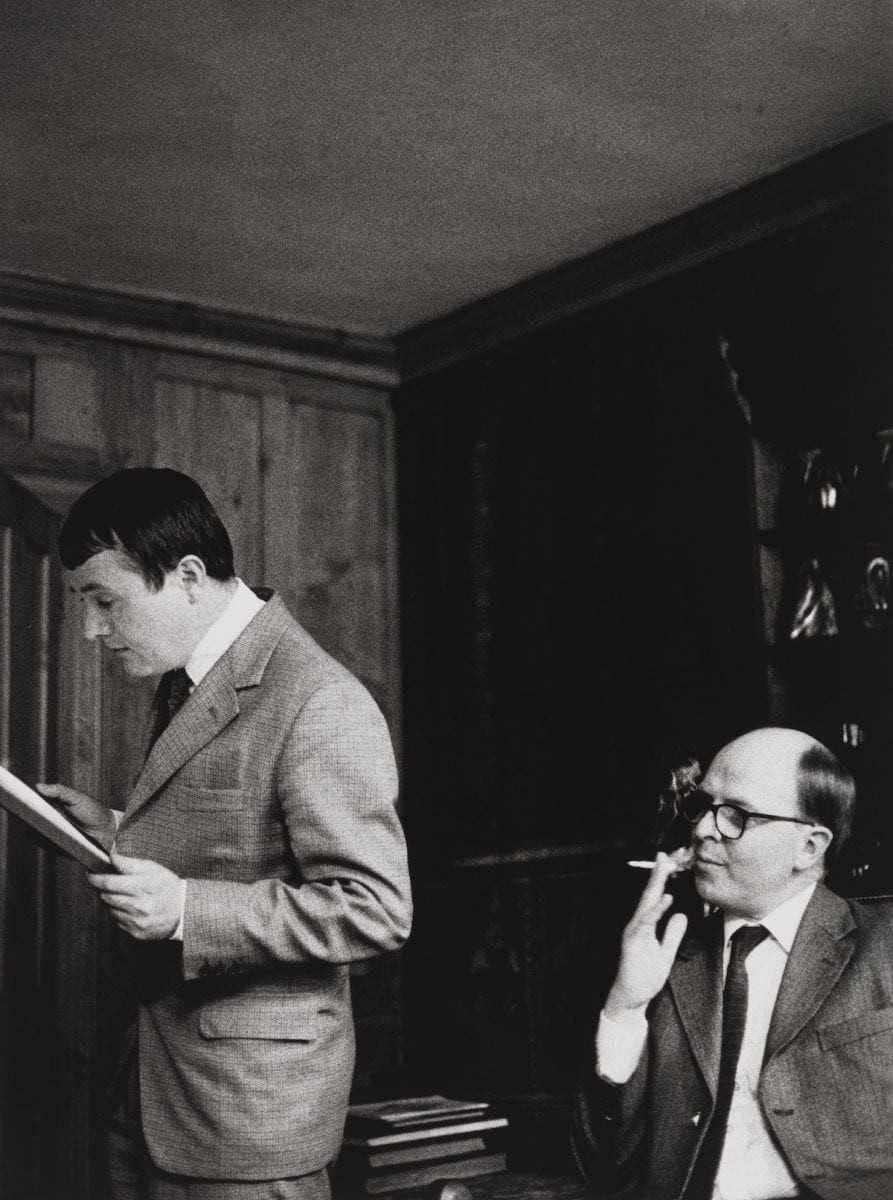

Seen through Gwinnutt’s lens, the men come alive with their own frustrations and desires, anxieties and aspirations, as they begin to make their way as artists, film directors, fashion designers and writers. This is not a document of celebrity, although some of its faces were famous already at the time—older figures like Gilbert & George and Norman Rosenthal—but rather a diaristic insight into a tight-knit scene fighting to survive outside of the conventional expectations of society. It is a life less ordinary to be found in these photographs, where the challenges (personal and political) of being openly gay are left unspoken but never far out of sight.

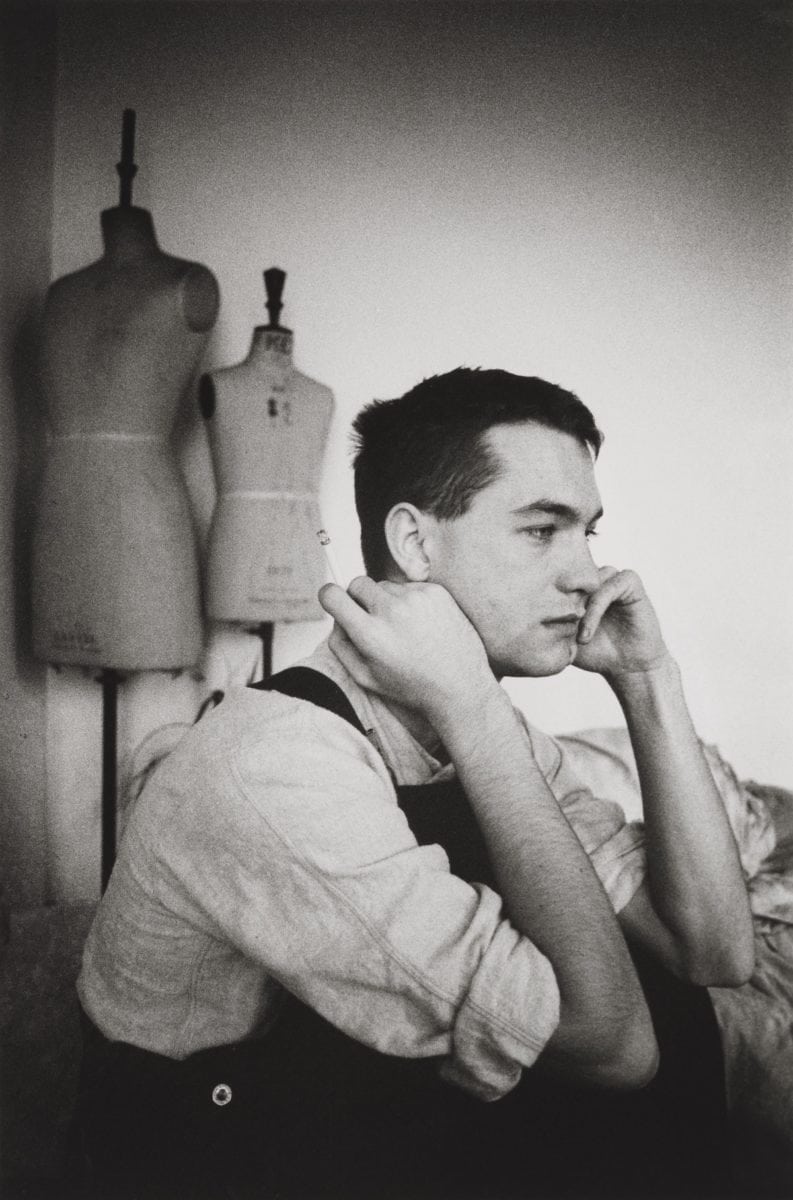

All the images in The White Camera Diaries were taken when Gwinnutt was in his early twenties, a hopeful newcomer to London from Derbyshire. “Every kid searches for their identity, don’t they?” he writes in the introduction, looking back almost thirty years after these images were first taken. “I knew from a very early age I was attracted to men and that this was really bad, even criminal and possibly made me like those men you occasionally heard adults talk about in disgusted terms, but somehow I knew I wasn’t bad.” His recollections and candid reflections accompany his photographs of the period documented in the book, spanning 1980 to 1986.

“These are images that take on the casual air of relaxed familiarity, made all the more remarkable for the famous faces that they contain”

- Left: Gilbert & George; Right: John Maybury; both 1982-1983

- John Maybury, 1982-1983 from The White Camera Diaries

We are given insight into the conversations and events that took place immediately before and after many of the photographs were taken, with Gwinnutt filling in some of the gaps that would otherwise be left blank. On meeting Derek Jarman for the first time, he writes “I wanted to photograph him and become his boyfriend or at least have sex with him.” His openness has a levelling effect, inviting us into the scene and reminding us that the glamour of a single image can often be misleading. He describes visiting the fashion designer Ossie Clark at his home, soon after their first meeting at a party in a Mayfair gallery. “It was very bleak inside. The walls hadn’t been painted in a long time,” he recalls. “He was quiet, polite, helpful, tired. He seemed sad.”

After photographing Clark reading his book and taking a bath, Gwinnutt produced a print that the designer requested from him. “He liked it and said in a demanding kind of way that I should give it to him. It caught me by surprise and I said ‘No’. I felt like he was snatching it from me.” Instead the young photographer stated that he would only part with it for the sum of one hundred pounds—“I was deluded because I still thought he was rich”—and a handwritten letter from Clarke in response is included. Sad and funny in equal measures, it includes such choice lines as “you are off your bonce”, “perhaps if I were Paul Getty the Second” and “try to practise the gentlemanly Act of Generosity.”

“It is a life less ordinary to be found in these photographs, where the challenges (personal and political) of being openly gay are left unspoken but never far out of sight”

- Left: David Holah, circa 1984; Right: Derek Jarman, 1982

Other letters and assorted notes exchanged at the time feature in the book, which emphasize the tight-knit nature of these relationships. This was the pre-digital era, when the locality of a place and the people in it really mattered, and a creative scene needed proximity to flourish. Gwinnutt reflects on this when we speak briefly on the phone: “In the age of social media it’s different, and it’s easier to be well known, to get attention. Back then, it meant more to be famous. It was more focused, and it lingered in the mind for longer. People mingled, and it was inspiring to be around them.” London itself is without doubt the unspoken backbone of the book amidst a glittering array of characters, and the exact street where a photograph was taken is recalled by Gwinnutt with dizzying accuracy: Roseberry Avenue, Fournier Street, Charing Cross Road. Iconic clubs, from Blitz to Heaven, also feature. The portraits come together as an alternative map of the city.

Last year, the National Portrait Gallery acquired twenty-one of the photographs featured in The White Camera Diaries, and exhibited them in a show titled Before We Were Men, timed to coincide with the fiftieth anniversary of the decriminalization of homosexuality. It is an important document of an era when queer culture and a wider creative scene empowered those who had formerly been repressed to no longer live in hiding, demonstrating to them and to a wider mainstream that there was no shame to be found in being gay. There is a powerful solidarity that resonates throughout the pages of the book, of friends, lovers and acquaintances united by their shared experiences.

Gwinnutt’s account of the period is infused with optimism, a mood that he describes was widely felt at the time. There is no mention of the dark shadow of Aids to come, something that he reflects on over the phone: “We were still in a period of celebration, excitement for the future. Then I moved away from London, and that’s when Aids came. My time in London was a positive story, and so many gay stories are so negative, of isolation or bullying… I wanted to tell something different. For many people, that wasn’t the end.”

“There is a powerful solidarity that resonates throughout the pages of the book, of friends, lovers and acquaintances united by their shared experiences”

- Left: Duggie Fields, 1982; Right: Trojan and Leigh Bowery, 1983

The White Camera Diaries—named after the white-painted camera that Gwinnutt used throughout his time in London—tells a story of youthful personal discovery, a coming-of-age tale that resonates beyond the specifics of its time and place. The photographs and accompanying anecdotes capture the specific yearnings of the young: the desire to be cool, the thirst for new experiences, the intensity of friendships—and the inevitable embarrassments absorbed along the way. After all, we change and develop as much through our mistakes as through our successes. It is not always the experiences themselves that are meaningful, but our understanding and perception of them. Of his first meeting with Ossie Clarke, Gwinnutt writes, “It was a casual encounter but I felt it counted.” Much the same could be said of The White Camera Diaries as a whole; spontaneous, thoughtful and profoundly human.