“I think all of you came in this morning and thought, ‘Where’s the show? Not much here…’” In the foyer of Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, Antony Gormley is explaining the set up of his new exhibition, Subject. There is only a handful of his sculptures, and we are directed to interact with lines that intersect the gallery, as if they might be sculptures themselves rather than structural elements of the building’s architecture. “The point is that you are the show,” he says.

The profile of public art in Britain has grown in recent decades, with regular commissions such as the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, and the presence of long-running organizations like Artangel. If the outside world has become a gallery over the past few decades, perhaps galleries themselves can be seen as merely another part of a cultural landscape that many have become accustomed to—one in which the line between public and private is blurred.

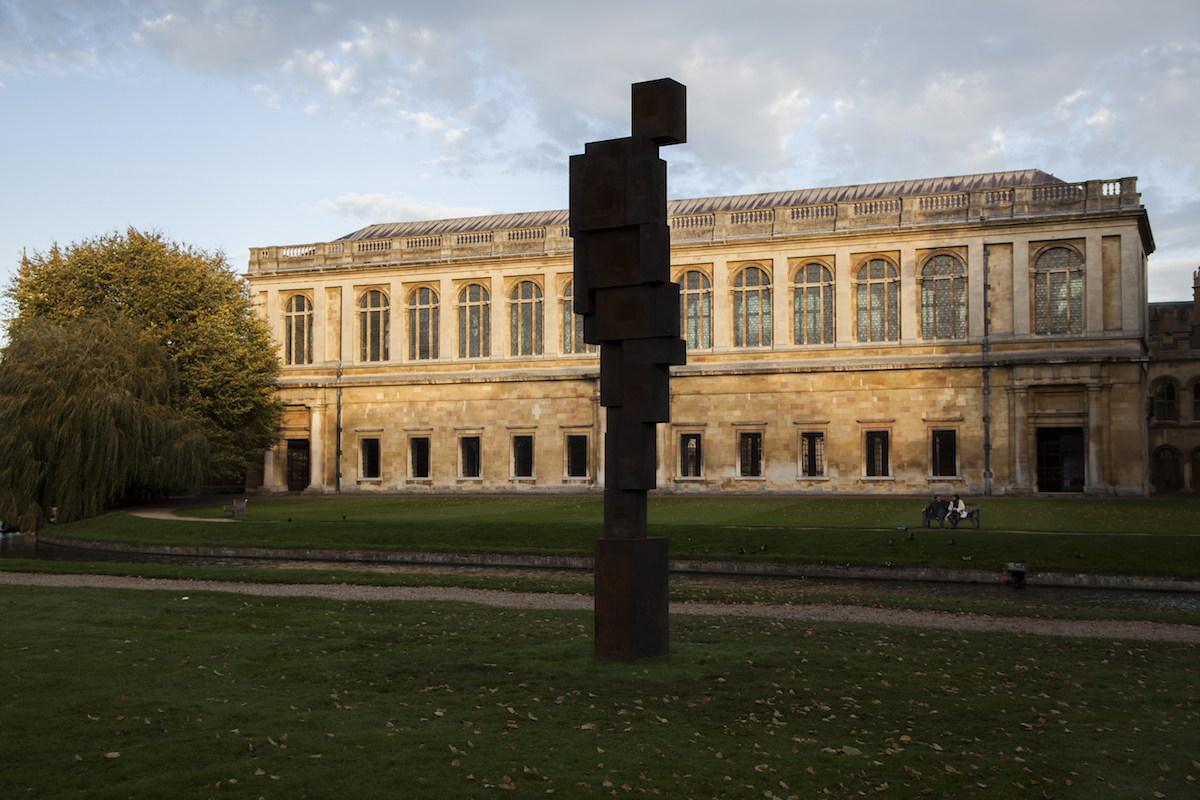

The eponymous piece in Gormley’s show—a humanoid form constructed of steel rods—looks out of a gallery window onto the street, becoming a public sculpture even as it remains inside. The town of Cambridge itself has multiple Gormleys. The ten-tonne cast iron totem Free Object (2005), on loan to Trinity College, intrudes on a nostalgic dreamscape of punts and the hazy River Cam, with students and geese sharing its lawn-space. It casts a strange modernist shadow over this unchanging halcyon scene, which can be seen to actively resist change through the sheer weight of its illustrious history. A gallery, says Gormley, is a “space devoted to art”. But so, it would seem, is a street, hillside or horizon.

“If the outside world has become a gallery over the past few decades, perhaps galleries themselves can be seen as merely another part of a cultural landscape that many have become accustomed to”

In the sixties and seventies, British Land Art made by the likes of Richard Long, Andy Goldsworthy and David Nash involved manipulating trees in Welsh forests, walking heavy lines through fields and embedding discreet, ephemeral works in the natural world around us. This was public art in the sense that the public could encounter it outdoors. However, their remote locations in secluded spots meant that you tended to see it only if you sought it out, and could miss it if you didn’t. You might as well be making a pilgrimage to a gallery.

The turning point came around 1993. In the same year as Gormley became represented by a British gallery, Artangel—an organization that had been quietly shaping the artistic landscape from behind the scenes for a few years—enabled Rachel Whiteread’s controversial Turner Prize-winning sculpture House to generate national debate that truly justified that term “public art”. The years following also saw Tony Blair’s New Labour government throwing money at public art, and establishing the Fourth Plinth, where the public are themselves solicited for thoughts on what art should be erected in Trafalgar Square. Those were the years of Gateshead Council’s literally monumental decision to commission Gormley’s Angel of the North.

Michael Morris, one of the directors of Artangel since the year Whiteread’s sculpture went up in 1993, tells me over the phone about how, in the past thirty years or so, “there’s been a change in public understanding and acceptance and valuing of work. Gormley’s pieces were controversial to begin with and now they’re national treasures. Whiteread’s House casts a very long shadow. It’s twenty-something years since it was destroyed and it still feels quite radical.”

“There’s more of a sophisticated understanding of the lasting value of sculpture outside of a museum”

While one of Tracey Emin’s handwritten neons now adorns St Pancras Station (unveiled this April), currently occupying the Fourth Plinth is American-Iraqi artist Michael Rakowitz’s The Invisible Enemy Should Not Exist, which is a tin can recreation of a 2700-year-old sculpture of an Assyrian deity destroyed by Isis in the Iraqi city of Nineveh. The discourse around public art, it would seem, has come full circle: engaging, popular and newsworthy public art can now be made about the public art and monuments of past civilizations.

Roger Hiorns, Seizure, 2008

“Visual culture doesn’t inspire as much fear in people of this country as it once did,” Morris tells me. “There’s no longer a sense of shock or confusion. There’s more of a sophisticated understanding of the lasting value of sculpture outside of a museum.” Morris names Roger Hiorns’s now-iconic Seizure (2008)—a UV lit, crystal-covered interior of a council flat—as an Artangel-funded work that has demonstrated the shift in perception. “Its first iteration in Southwark made people think again about what public sculpture could be. It was extraordinary to us that it was relocated to Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Though of course it’s part of the landscape, it’s still a traditional place where we go and see sculpture.” Recently, Ryoji Ikeda’s Spectra—in which forty-nine beams created a column of light piercing the sky from Victoria Tower Gardens near the Houses of Parliament—showed the public who flocked to it that public sculpture didn’t have to be seen on a plinth, and could be made of any material.

“Nowadays public art, often inspired by or derivative of Gormley, is so ubiquitous you find yourself wishing that you could walk along a coastline without a sculpture”

“The fact is,” Gormley agrees, “there is now a more common engagement with art. It exists within the national consciousness.” I wholeheartedly agree. Growing up in Newcastle, I remember when the Angel of the North was completed, when I was aged around nine or ten. There are pictures of me in family albums posing at the foot of the sculpture when it was under construction, a single wing attached. Now, having moved south, if I come back to visit by road, the Angel appearing as I come up the A1 will tell me that I am home. It is fair to say that the Angel was my first conscious experience of public art, and also that it has influenced the way I see my homeland from the outside, as I re-enter that space. The same is true for many of my generation. Indeed, it was announced in 2015 that the Angel would be included in the pages of the new British passports.

But anything that lodges itself in the public consciousness can also become a cliché. Nowadays public art, often inspired by or derivative of Gormley, is so ubiquitous you find yourself wishing that you could walk along a coastline without a sculpture. Near to where I grew up, Sean Henry’s Couple (2008) faces out to sea from a scaffold on Newbiggin Bay; his two figures have the plasticine unsightliness of a 3D Beryl Cook realization. Damien Hirst’s 2012 statue of a skinless pregnant woman with a sword, Verity, on the Devon coast, was unfortunate enough to annoy half the Ilfracombe population and alienate the already art-loving British as well. When I suggest to Gormley that these works are no doubt influenced by his more thoughtful works he says, “I’m not sure I’m very proud of that.”

In 2017, almost twenty years after their introduction to the Crosby coastline in Merseyside, a handful of the hundred figures comprising Gormley’s Another Place were either defaced or decorated with spray paint bikinis and t-shirts, depending on which way you look at them. Members of the public were outraged, and Gormley requested the council remove the graffiti. Another Place, Gormley tells me, has consistently meant something to those who “have found some solace to do with either losing their own life thread, or losing a loved one”. Dealing with grief, for them, melded with how “the pieces appear and disappear towards the horizon”. But there are two spirits of public art, and they are not both benevolent. Public art is also a Banksy; it has at times been seen as its own form of vandalism. By Gormley’s own rules, which encourage the natural denaturing and alteration of the sculptures—rust, barnacles and all—the self-consciously witty graffiti could be classed as a valid interaction between world and art. And it would have been an interaction with the world when, during the Autumn of last year, a ship almost collided with the Gormley sculpture out to sea in front of Margate’s gallery Turney Contemporary. The art angel can also be one of destruction.