For her baptism of fire in the London arts scene, the budding talent has poured years of body shaming and religious trauma onto works that flip the middle finger to perfect(ed) views of femininity

When I log on to the Microsoft Teams video call scheduled for 7 November to discuss the making of her eponymous debut solo show, 25-year-old Spanish artist Elena Garrigolas looks slightly uncomfortable in front of her laptop camera. It is 11:32 am, and, yes, I am two minutes late, but I doubt those 120 seconds have anything to do with the thin veil of nervousness that I perceive while looking at her half smile from my South East London bedroom. “Can we start?” she says, drastically cutting through my pre-interview, neurotic small talk. I must have become too British, I think to myself, realising I have given in to the sheer politeness and weather-related chat that only those who have lived in the UK for a fair amount of time are used to digesting daily. “Sure thing,” I reply promptly, desperately trying to make up for my fast-disappearing, no-bullshit Italianness. After all, I have always been a sucker for some good old Southern European camaraderie; hence making a decent first impression on Garrigolas would automatically mean feeling slightly closer to… home.

Sitting in her flat in Girona, Catalunya, where she relocated from her parent’s house in a small town of the same region, the artist tells me that she has just come back from the opening of her first-ever exhibition. Launched on 1 November at Saatchi Yates — one of the numerous contemporary art galleries taking over London’s affluent neighbourhood of Mayfair — the showcase is so intrinsically linked to her upbringing that it is impossible to delve into it without inevitably opening the Pandora’s box that is Garrigolas’ childhood. Now, thinking back to the uneasy look she gave me at the very start of our conversation, I suddenly understand where that came from: it is not every day an internationally recognised art institution DMs you on Instagram inviting you to put together a new body of work for them, let alone when the work is so personal. But, believe it or not, that happened to her. “They found me on Instagram a while ago and bought some of the paintings I had on my website,” Garrigolas says. “After receiving them, they contacted me again and were like, ‘We want you to make a whole show for us.'”

Picture this. You are a Class of Covid-19 graduate — Garrigolas studied Fine Arts in Barcelona and received her degree in the summer of 2020 — still waiting for your moment to arrive when an unexpected message from an established gallery turns your world upside down. “I started crying when I saw it,” she recalls, adding that had Saatchi Yates reached out to her only a couple of months later, it would have probably been too late. “Two weeks before receiving that DM, I was ready to quit,” Garrigolas explains. “After graduating, I had given myself up to three years to start getting some results: I was drawing every day and posting my work on Instagram, but since nothing was really happening art-wise, I was considering getting ‘a real job’. I guess Saatchi Yates saved me on time.” Judging by the light igniting the eyes of the rising painter as she recounts her artistic breakthrough, it is clear that her practice means a lot to her. From her words, you get a sense that, long before the British gallery discovered her, it was art in itself to save her.

“I grew up in a hyper-Christian family, went to an all-girls Catholic school and was raised to believe in the preaching of Opus Dei — a slightly culty Spanish religious group whose goal is to transfer Christian ideals into people’s professional, social and family life,” Garrigolas says. Brought up in what the artist describes as “a bubble”, she wouldn’t be allowed to spend time with anyone living outside of it, and especially boys. Throughout her childhood and teenage years, there was never a space for Garrigolas to address her thoughts, feelings and discontent with her circumstances. “I always found it really hard to express myself with words because I knew that anything I said was going to be judged and dismissed by my parents as invalid or not in line with their values,” she explains. Confused as to why a religion that praises itself for showing people how to love could generate such a disconnect in her household, Garrigolas sought answers in art. “Every time I felt like voicing my emotions, I would just go mute,” she says. “With drawing, I didn’t only unlock a way of translating what I feel onto paper, but I also created an opportunity to talk to and confront people, implicitly saying things that I wouldn’t have the courage to say in any other way.”

The collection of paintings currently on display at Saatchi Yates, which comprises large-scale renditions of works Garrigolas had previously developed and three brand-new canvases, oozes her thirst for liberation. Anything but prudish or compliant, the artist’s deliberately bizarre and grotesque take on the body, motherhood and femininity — the core themes of the exhibition — is a trippy journey to reckon with. When I talk to her, I have just spent days doubting myself, the way I look and how others view me. Having dealt with body dysmorphia since my early teens, I am periodically dragged into overthinking spirals that see me struggle to accept my skin and avoid comparisons with the social media-driven, contemporary notion of beauty. Needless to say, feeling understood by another female peer is incredibly uplifting. “Art has been a real form of therapy for me,” Garrigolas says, reflecting on how honing her craft allowed her to reconcile with her body.

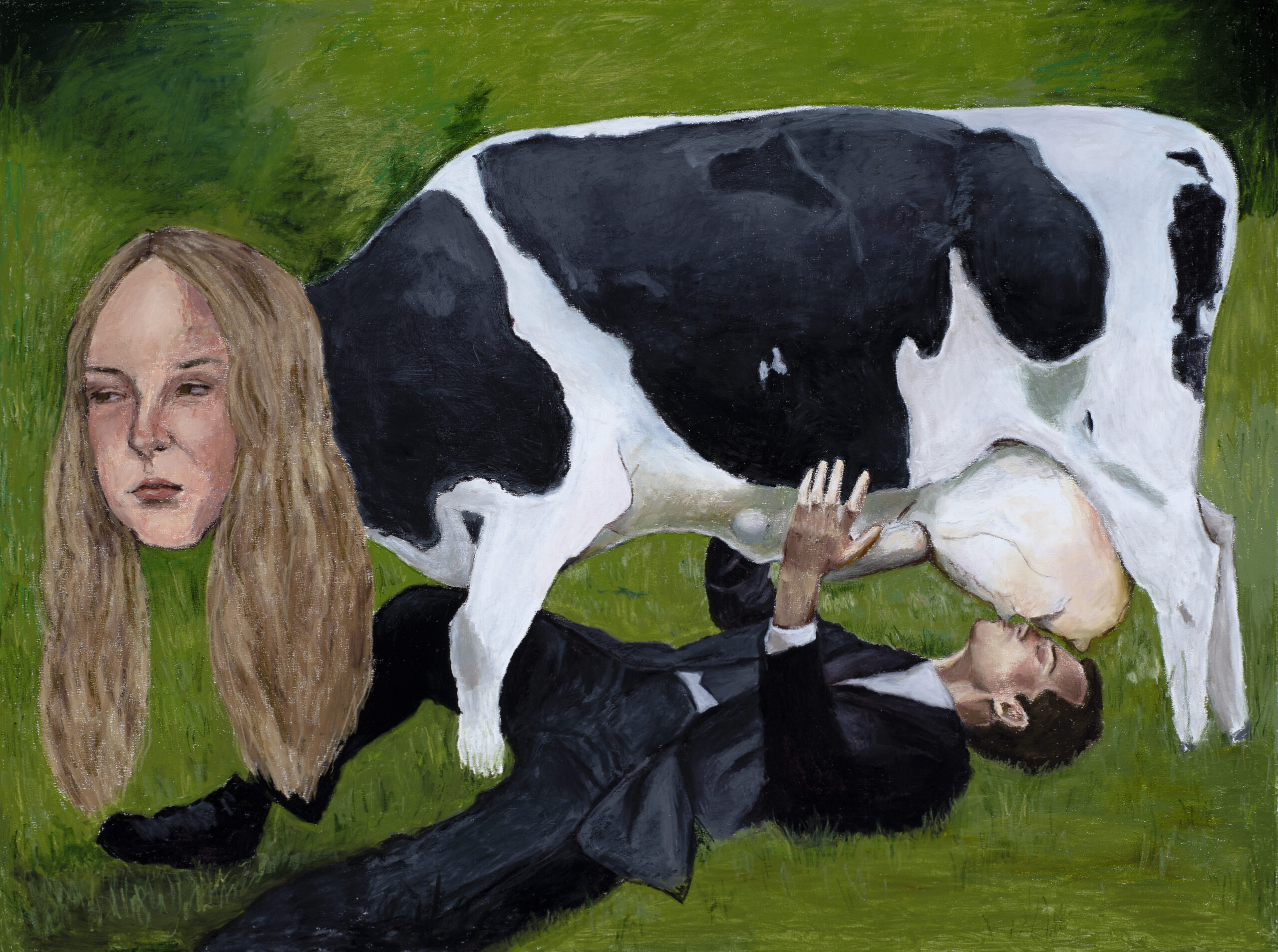

For the painter, who was taught to cover up and dress down not to attract the male gaze from a very young age, controlling the way people see her through a curated online presence was the norm for a long time. “I got to a point where I couldn’t take a single picture of myself without having a filter on,” she explains. “Before posting anything on social media, I would always make sure that my body looked perfect and my face was flawless. So far, my drawings have been the only thing that encouraged me to accept myself as I am.” From categorically refusing to leave the house with her hair in a bun or no makeup on to painting self-portraits that liken her to cows, slugs, elderly women and freakingly deformed silhouettes, Garrigolas’ journey to self-acceptance escalated rather quickly. Still, rather than offering definitive solutions for her insecurities, art only acts as a coping mechanism. “It is my way of trying to understand how to get over these fixations, these fears,” she says, among which stands out her fear of getting older.

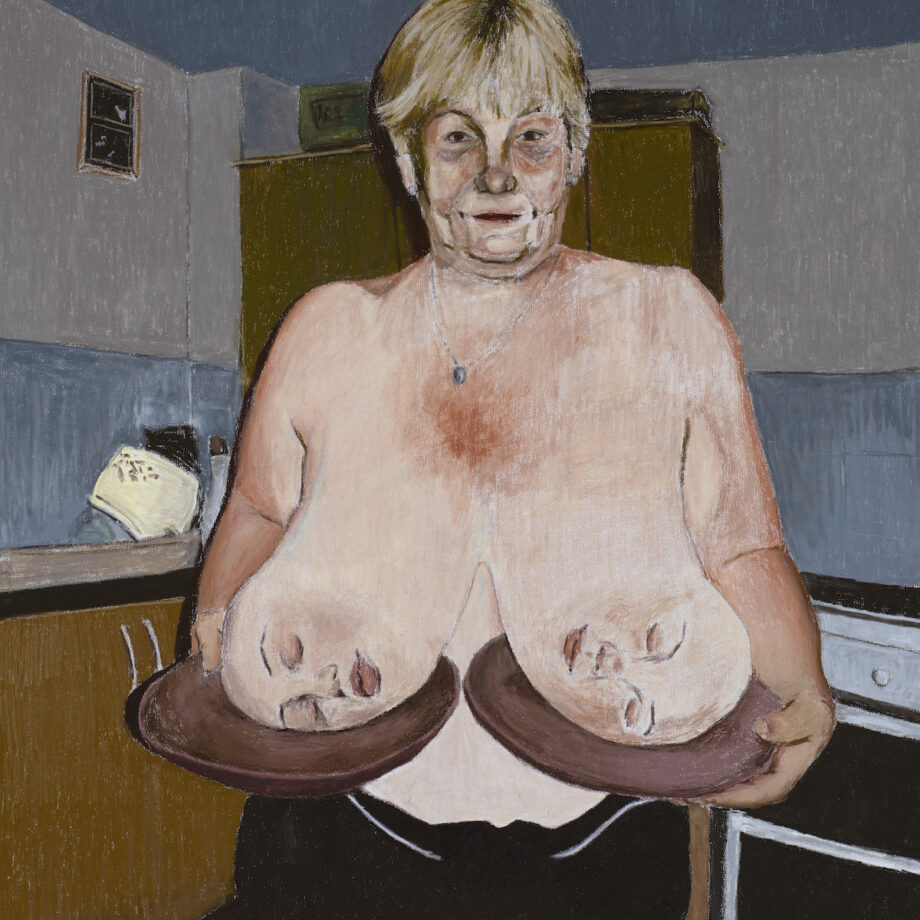

In 2023, we can expect to see chubby 60-somethings date unrealistically fit young models that “basically wake up with their mascara on”, Garrigolas laughs. Instead of accepting the call for continuous self-improvement that has been historically imposed on women — the idea that allowing yourself to be and age naturally leads to a decline in your sex appeal and overall attractiveness — in her surreal compositions, the artist captures real bodies to rebel against toxic conceptions of womanhood and inspire positive change. “I think creativity can grant women an opportunity to shift how they are thought of and perceived,” she says. “It should be fine to have grey hair and sagging breasts, to be able to stick to our own body shape without emulating someone else’s simply because that is what others want us to do.” Brought to the extreme, Garrigolas’ perspective on 21st-century beauty animates the 20 artworks presented in her London showcase through 22 December.

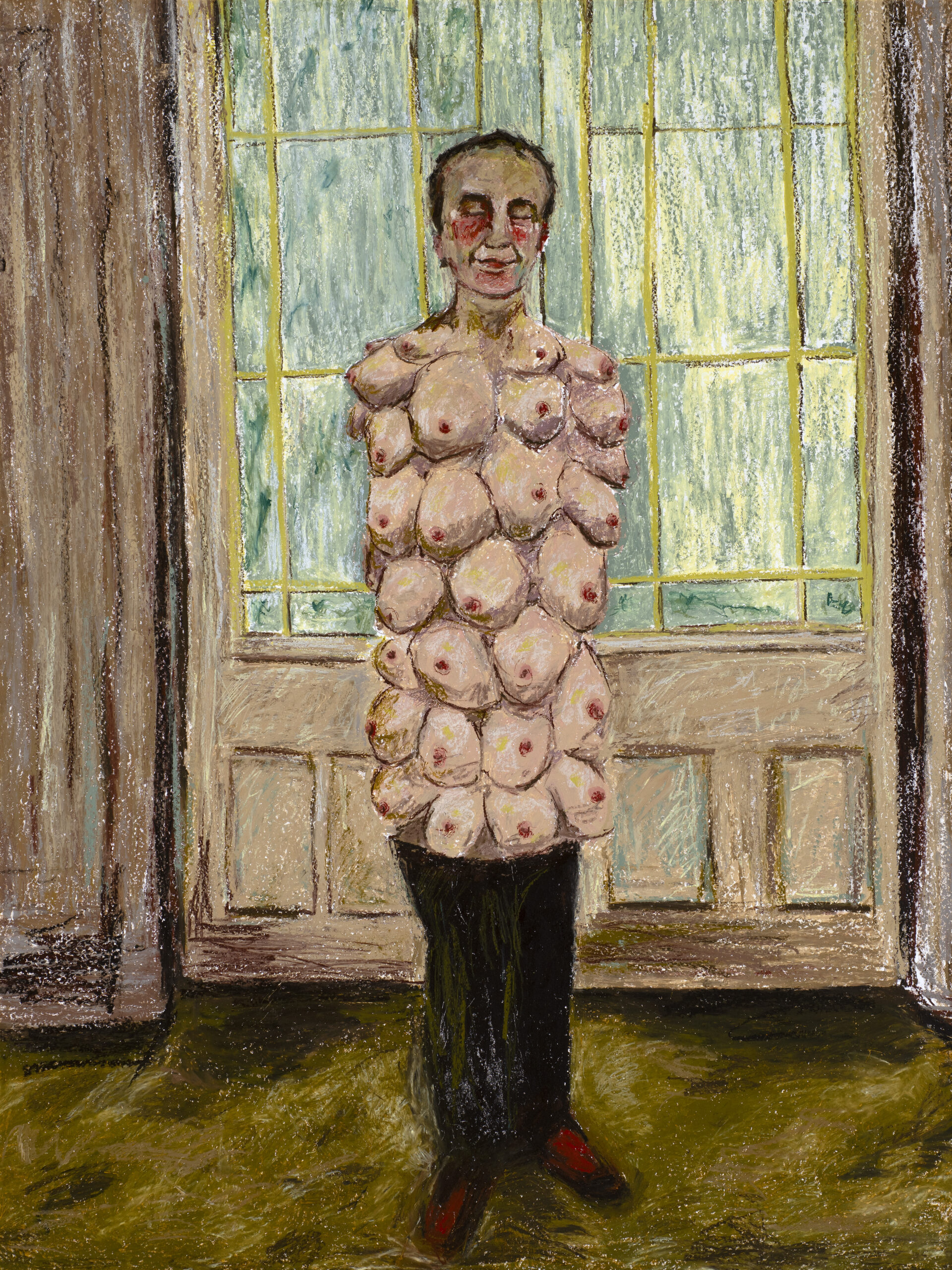

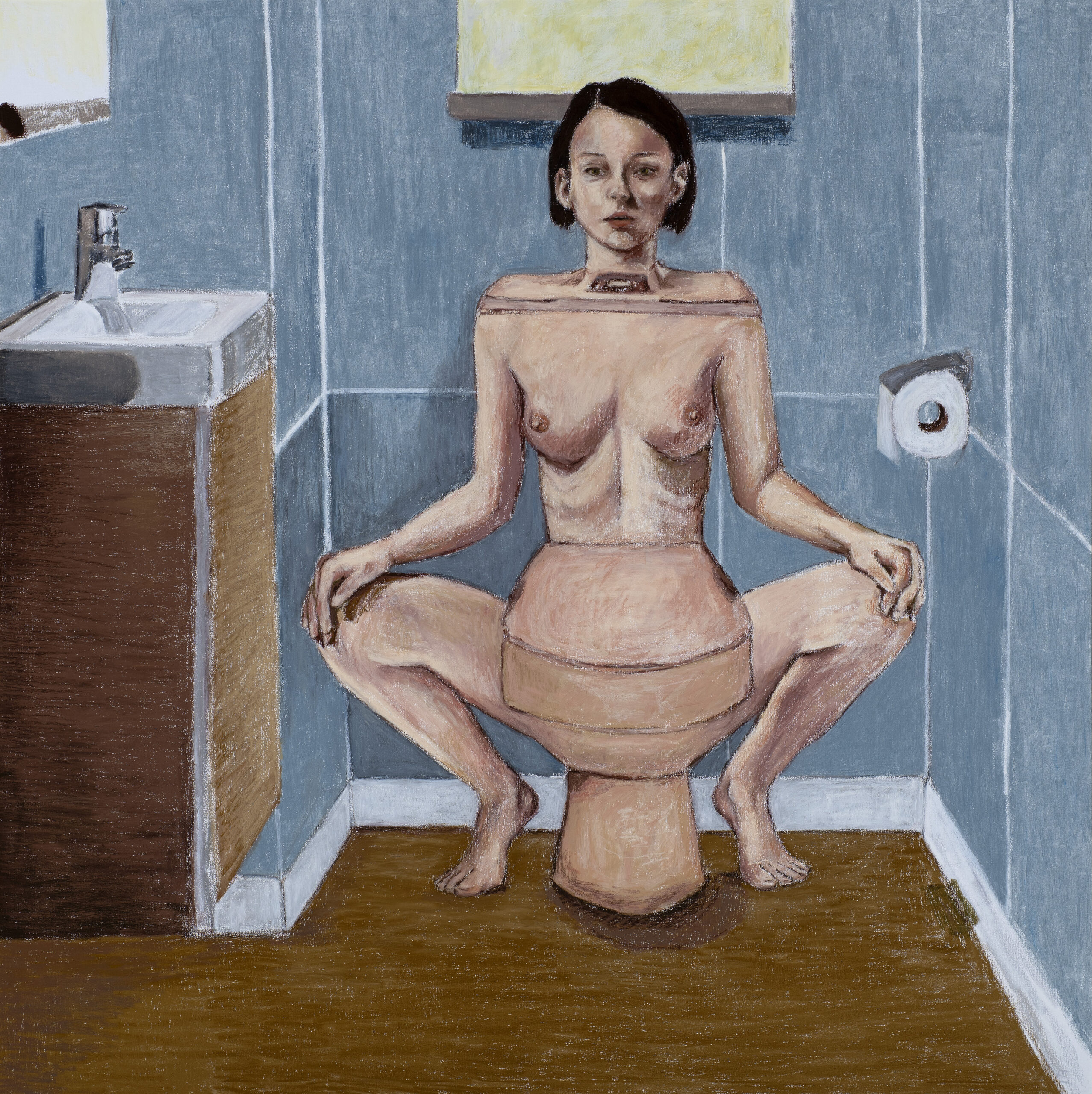

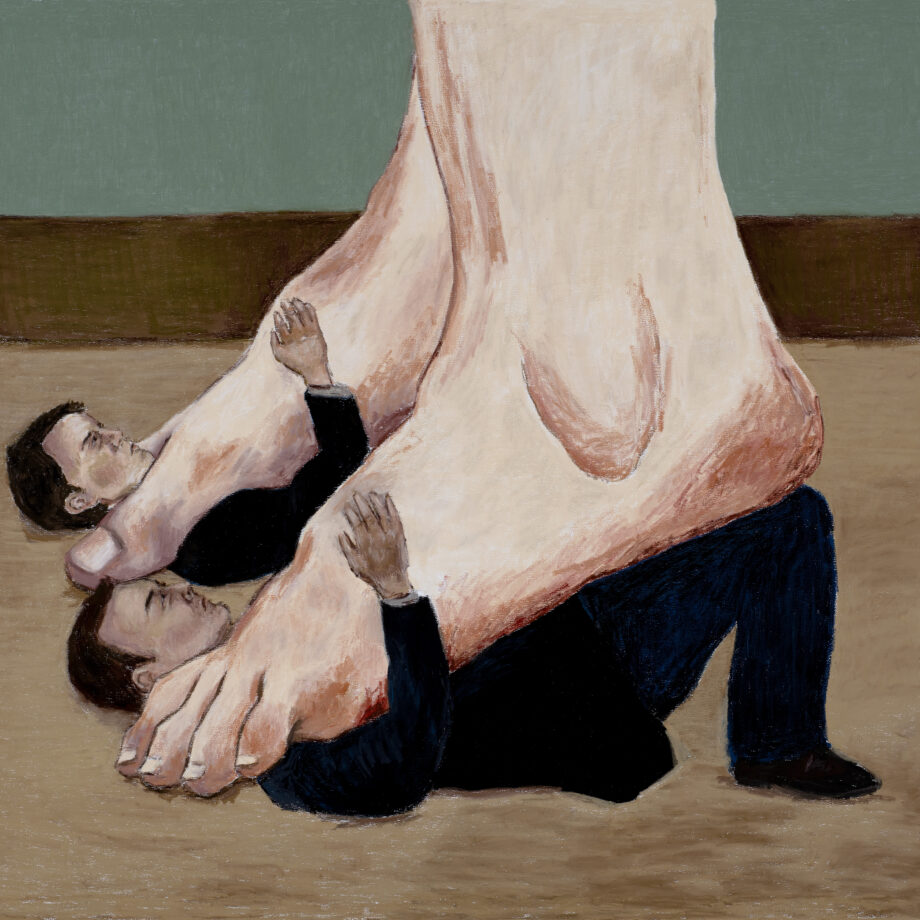

In Ideal Woman, a play on male expectations of femininity, an all-boobed man with no arms, just titties, blushes, satisfied at his own copiousness. In other uncanny canvases, screaming toddlers emerge from the sinuous buttocks of two female figures who, however, don’t seem to mind. Throughout the exhibition, Garrigolas’ subjects unveil themselves to viewers in the form of anything from an anthropomorphic toilet bowl (The mortifying ordeal of being known) to musical instruments (Portrait of a man playing the cello), life-size animals (Forever, and ever, and ever), shoes (New High Heels) and a number of body parts, including a woman’s own mouth (Wet Dreams). “If I were to choose, I would always pick ugly, visceral art over beautiful stuff: for some reason, part of me really enjoys being disgusted by things, the lack of restraint that comes with strangeness,” she says. “That is why I love outsider art — because it is badly drawn, there is no perspective in it, no proportions and yet, it tells a story, and you can really feel it.” Also informed by avantgarde feminist artists such as Frida Khalo, Miriam Cahn, Nancy Spero and Paula Rego, surrealist Japanese painter Tetsuya Ishida and the outlandish stop-motion animations of Czech filmmaker Jan Švankmajer, her latest series recasts years of religious trauma and guilt into provocative scenes that cannot go unnoticed.

“I wanted to throw some weirdness into people’s faces so that no one could look away,” Garrigolas says of the intention behind her newest paintings. Fusing her love of memes with more historic yet equally unearthly references, the artworks echo “the personified genitalia inhabiting the marginalia of mediaeval manuscripts”, she adds. Both sex and the sexualisation of women’s bodies are, in fact, two of the overtones hidden in these strikingly painted canvases, which the painter uses as a means of coming to terms with her own experience of them. Looking back at her university years in Barcelona, Garrigolas recalls sitting in her first life drawing class, unable to deal with the presence of a nude male model. “Before moving out of my parents’ house at 18, I had never had any male friends nor boyfriends,” she explains. “When that happened, it took me three weeks to get over it and accept to look at his penis.”

Much like the rest of her upbringing, her sexual awakening was brutally disrupted and overshadowed by the intrusive thoughts triggered by her parents’ conservative education.

“The first opportunity I had to compare my situation with a man’s came from my own family,” Garrigolas says. “I never understood why no one expected anything of my brother, why no limitations were posed to his lifestyle, while I was constantly reminded of what I could or couldn’t do.” Not having had the chance to experiment with dating before, when she eventually got to it, the artist felt an obligation to please their partners at all costs, even against her own will, a story most women know all too well. “Now I love myself better and, luckily, I know I am worth more than that,” she adds. Her relationship with men and herself is still a work in progress. Evocative of that complicated bond, My Milkshake Brings All The Boys To The Farm — another one of the paintings on view at Saatchi Yates — draws on the way Garrigolas felt when she first started sleeping with boys by comparing her to a cow that is being milked. “I would just let anyone do whatever they wanted with my body while laying down with that face,” she explains, referring to the visibly resentful look of the cow-woman in her canvas.

Despite making her more aware of her past, these humoristic caricatures of her sex life are not enough for her to feel empowered or in any way more confident. Instead, “I look at them as if they were a diary,” the painter says. “They help me organise my ideas, examine what I have left behind and what stands ahead of me.” With such an explosive debut solo exhibition, it seems only fair to say that Garrigolas’ journey has just begun. Had Saatchi Yates not pushed her into working on blown-up replicas of her previous creations, the Spanish artist would probably still be focusing on her drawings. Tested with a new challenge, she didn’t simply show what she is made of, but took it as a springboard to bring her craft even further. “Now that I know what I am capable of, I want to try other stuff as well, like installations and animations,” Garrigolas says. “As for the themes of my work, someone once said that what is personal is political and that what affects the body also affects society in return: although I am still healing, I am ready to put everything I have learnt so far into making art that helps me feel better, into creating a community that can help other women feel seen and feel better, too.”

Elena Garrigolas’ solo show is on view at Saatchi Yates through 22 December. All images courtesy of Saatchi Yates

Words by: Gilda Bruno