Penny Slinger’s landmark book of surrealist photomontage, 50% The Visible Woman, opens with an image of a bound woman staring back at us through heavily kohled eyes. Wrapped and gagged in surgical dressing, a target hovers by her head and the word “WANTED” is spelled out beneath her. She could be an escaped hospital patient, a character from a Georges Franju movie, or a proto-feminist fugitive on the run.

This image of punk provocation still feels fresh today, but the book was actually created in 1969, as part of the artist’s thesis project while a student at Chelsea College of Art. Slinger handmade three copies, giving one to the artist and historian Sir Roland Penrose, and another to her then lover, the filmmaker Peter Whitehead. Two years later, Whitehead’s publishing imprint Narcis released an abridged version of the book, which typeset what Slinger had originally typed by hand.

Over the decades, Slinger’s work has undergone periods of unjust critical neglect. The publication of a new and expanded 50th anniversary edition of the book is a welcome corrective.

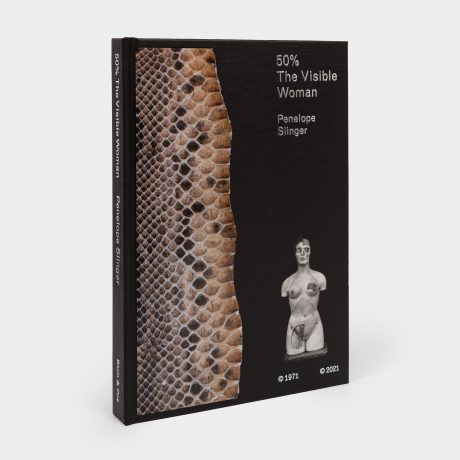

Created as a tribute to the collage books of the German Dada and surrealist artist Max Ernst, the original volume included poetry printed on transparent tissue paper, and the whole things was hand-bound in real snakeskin. She wanted the book to be “very tactile and very real,” the artist explains over Zoom from her studio in Los Angeles. “The way the flimsy paper felt in relation to the printed pages of photographs… this was a sensory kind of experience.”

“The book becomes both a self-interrogation of the artist’s psyche, and a broader inquiry into the role of the muse in art history”

The new edition amalgamates elements from the two earlier versions, with half the book’s cover showing the snakeskin binding, the other half the 1971 edition. A new, wide-ranging conversation between Slinger and influential artist Linder accompanies the publication. The artist behind the cover art for the 1977 single release of Orgasm Addict by the Buzzcocks, Linder has credited 50% the Visible Woman with influencing her own photomontage practice.

Slinger felt what she describes as a “true affinity” with Ernst. His images, Slinger explains, “were the stuff of fantasy, depicting the ‘normal’ world being turned on its head, of the ocean invading domestic scenes, of bird-headed beings and winged women, of art on the walls coming to life. I loved it because that was how I saw things too.”

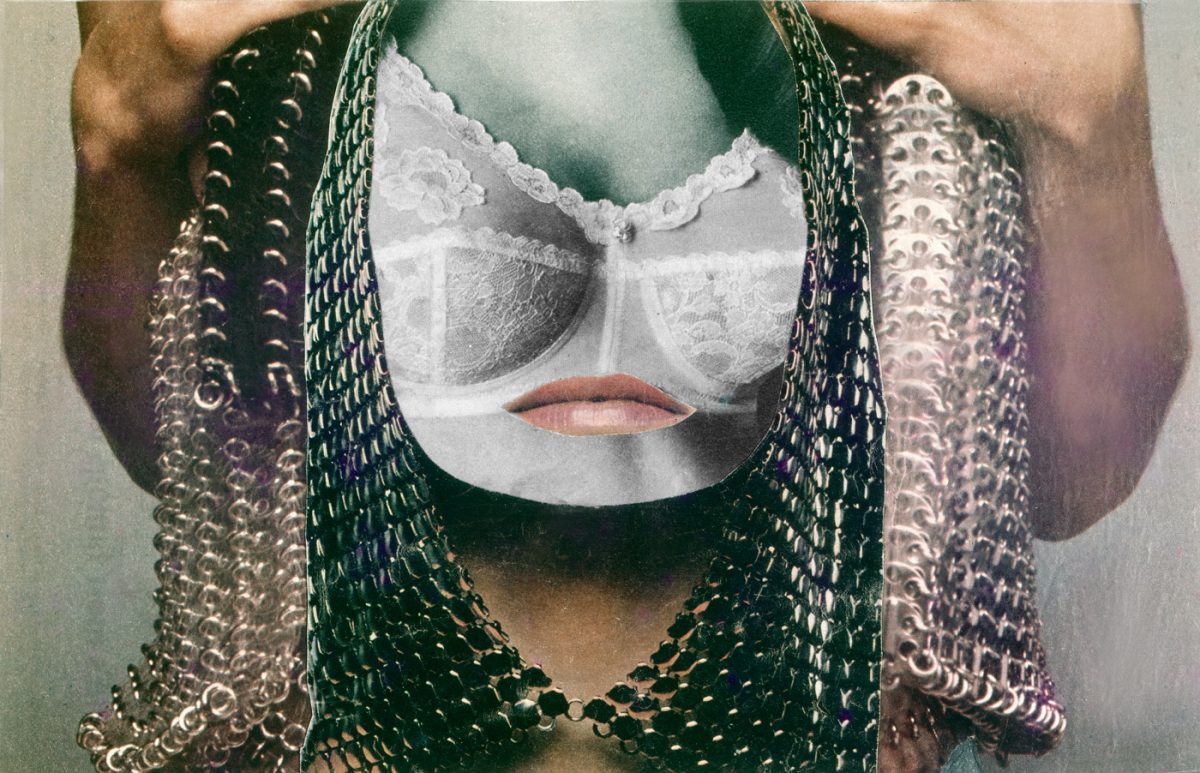

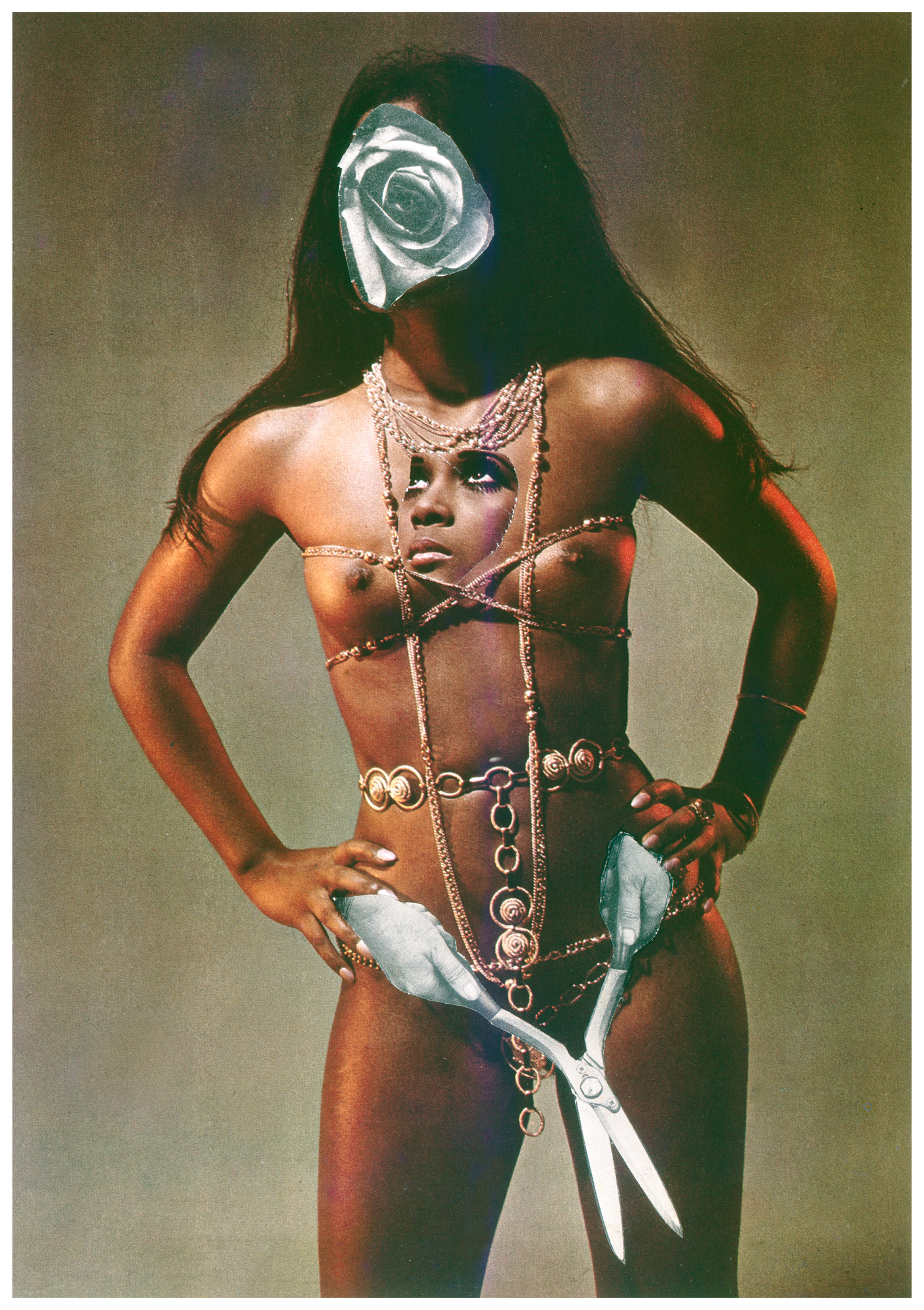

Rather than using engravings as Ernst did in his collages, Slinger turned to ‘found’ images and photography, often using herself as the model alongside her friend and creative cypher, the artist Suzanka Fraey. “I realised that what attracted me most in art was the use of the human, and particularly the female form, but not in a purely representational way: in a symbolic, mythical, mystical, magical and archetypal way,” she explains.

“I wanted to hold up a mirror in my work and encourage self-reflection, self-dissection, as I wielded my scalpel and scissors”

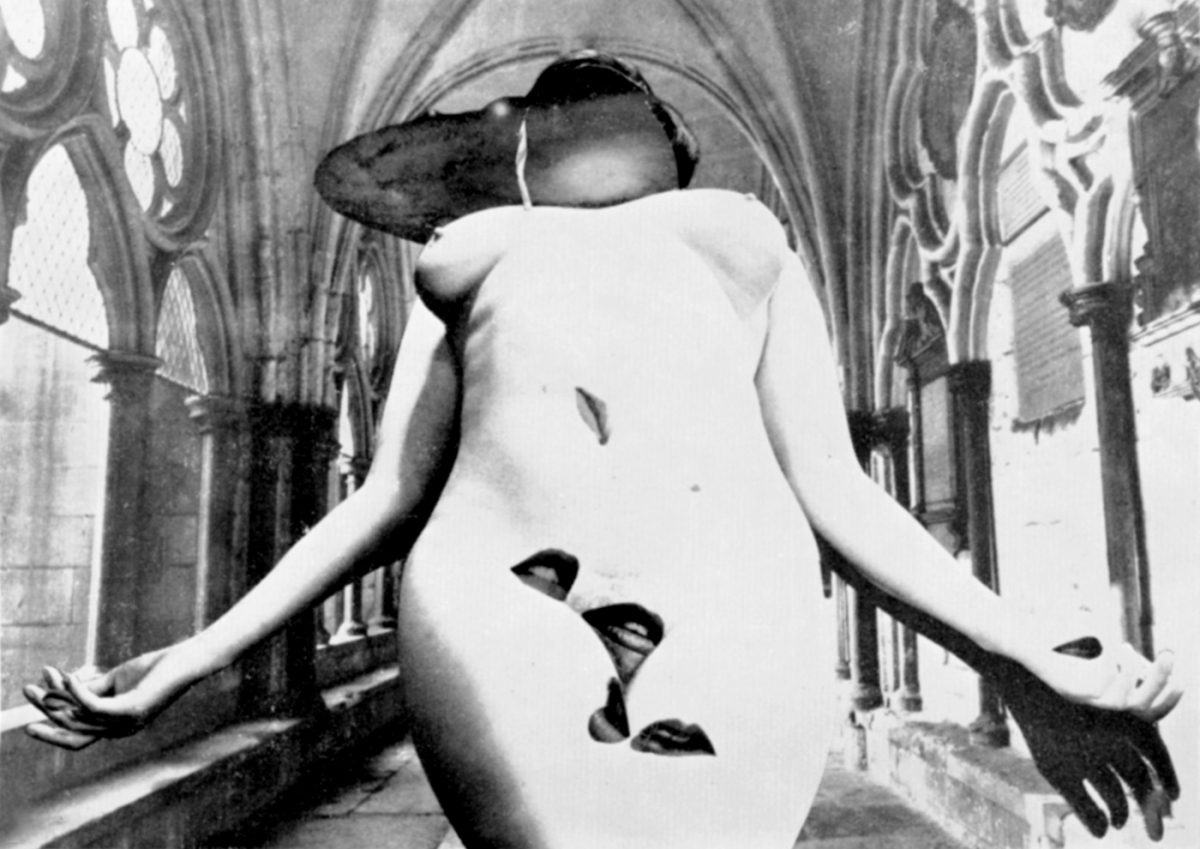

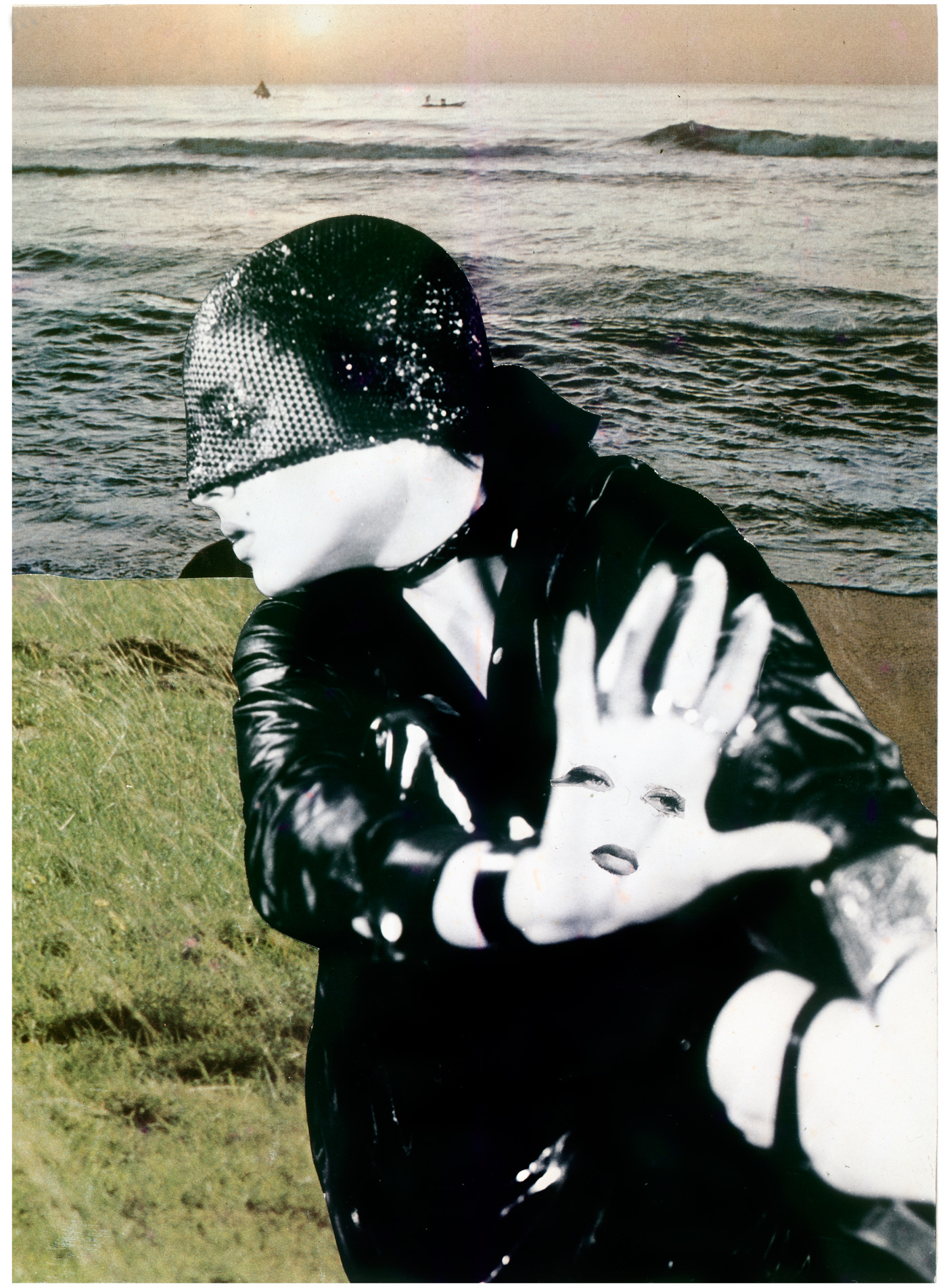

Slinger’s book employs the visual language of surrealism in a bid to fashion a new language for the female psyche. She emphasises the realms of the unconscious, of sexuality and desire to weave a dreamlike narrative around several unnamed women. This unfolds through a series of transformative and initiatory rites, including a ‘messy’ childbirth, a disembowelment, and a ritual sacrifice on the seashore.

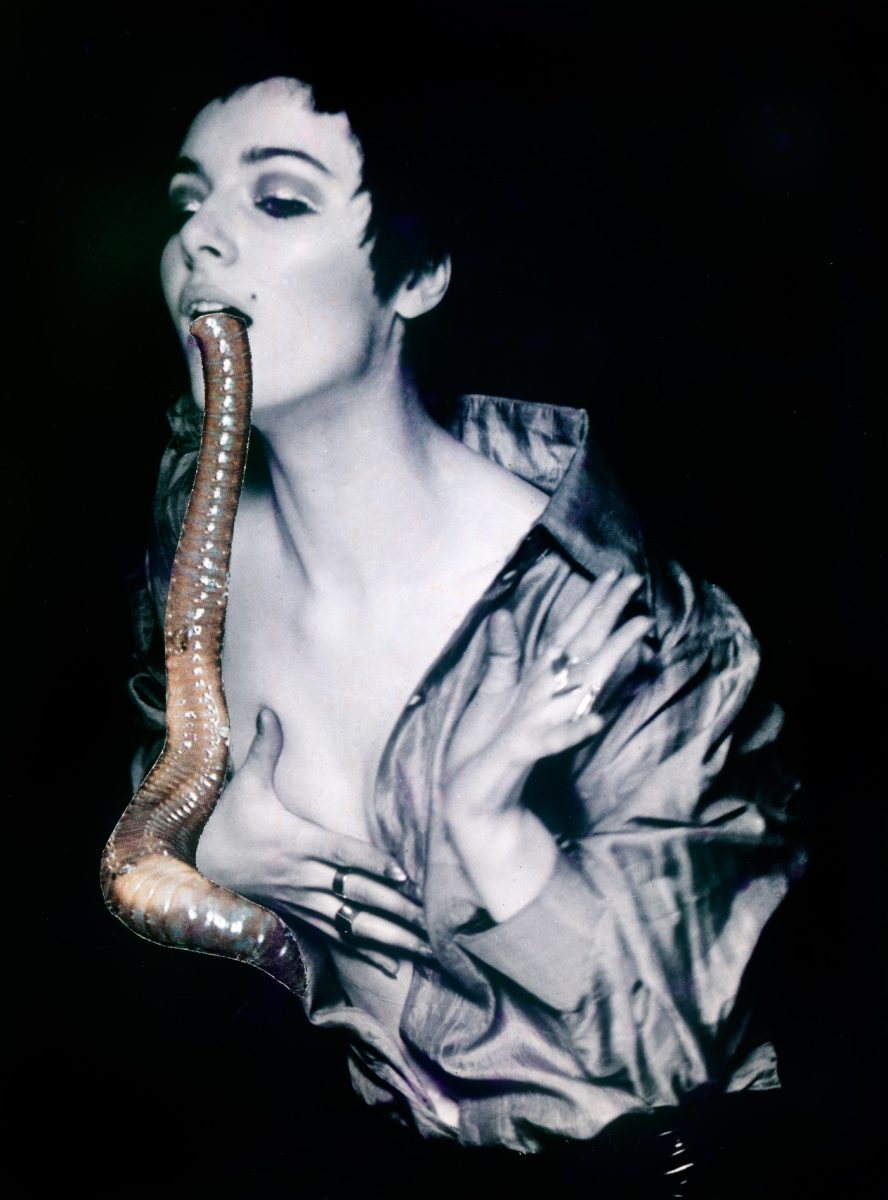

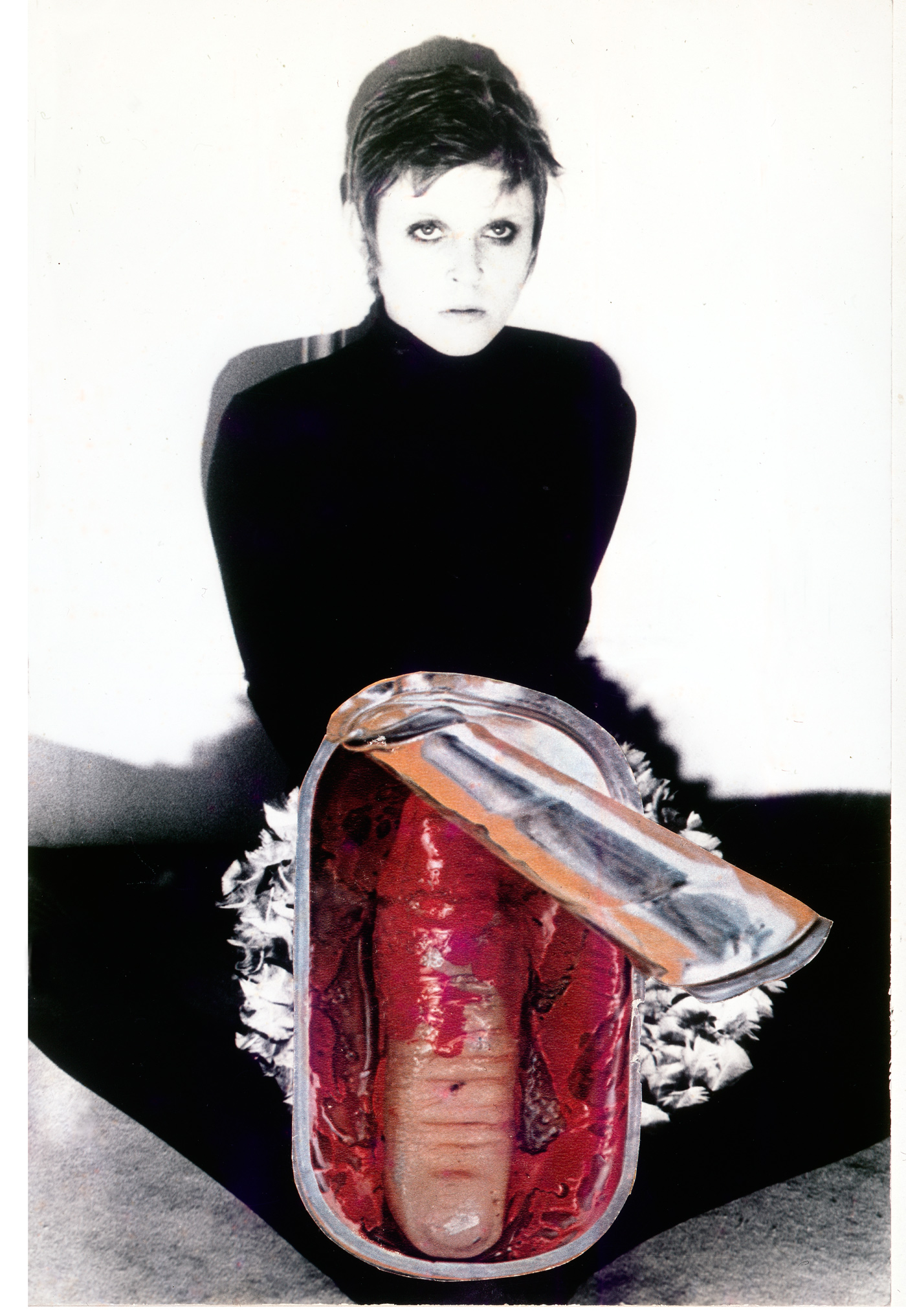

As much as the book deals in the flighty dimensions of inner space, of dreams and memories and repressed desires, it is firmly rooted in the bodily. Her poetry speaks of the rupturing of a woman’s “sack-of-blood body”, of menstruation and physical decay and afterbirth. While the images foreground the female body, they also show penises growing out of tree trunks, snakes emerging from an open mouth, fingers in tins of fish, brains and innards.

The book becomes both a self-interrogation of the artist’s psyche, and a broader inquiry into the role of the muse in art history. “So many men throughout the history of art lauded and portrayed their female muse, but where were the women, looking at themselves?” Slinger asks. “I wanted to hold up a mirror in my work and encourage self-reflection, self-dissection, as I wielded my scalpel and scissors.”

“Slinger’s book employs the visual language of surrealism in a bid to fashion a new language for the female psyche”

Slinger uses photomontage to deconstruct the passive figure of the muse, displaying found images of female nudes divorced of their artistic context. Slinger dismembers and radically rearranges women’s bodies, substituting parts to create metonymic connections, a comment, perhaps, on the dismembering tendencies of other male artists. In what Slinger playfully calls “full-frontal collage,” breasts take the place of a head or set of eyes, a vagina or belly button replaces the mouth.

Originally billed as a book of collage and poems, 50% The Visible Woman also included photography and documentation of the sculptural projects the artist was working on at the time. The seeds of Slinger’s cross-disciplinary approach, which would go on to encompass film, performance art, sculpture, collage, poetry, theatre, Tarot, Tantra, set design and fashion design, all sprout from this extraordinary book.

50% The Visible Woman ends in something of a call to arms to turn the page, to make a new start, to abandon the old language that is no longer serving us. At the centre of this is an awareness of its own printed and bound format, one of the most powerful weapons of all: “With each new beginning/ We open a book…”

Sophia Satchell-Baeza writes on films, psychedelic art, and the 1960s British counterculture