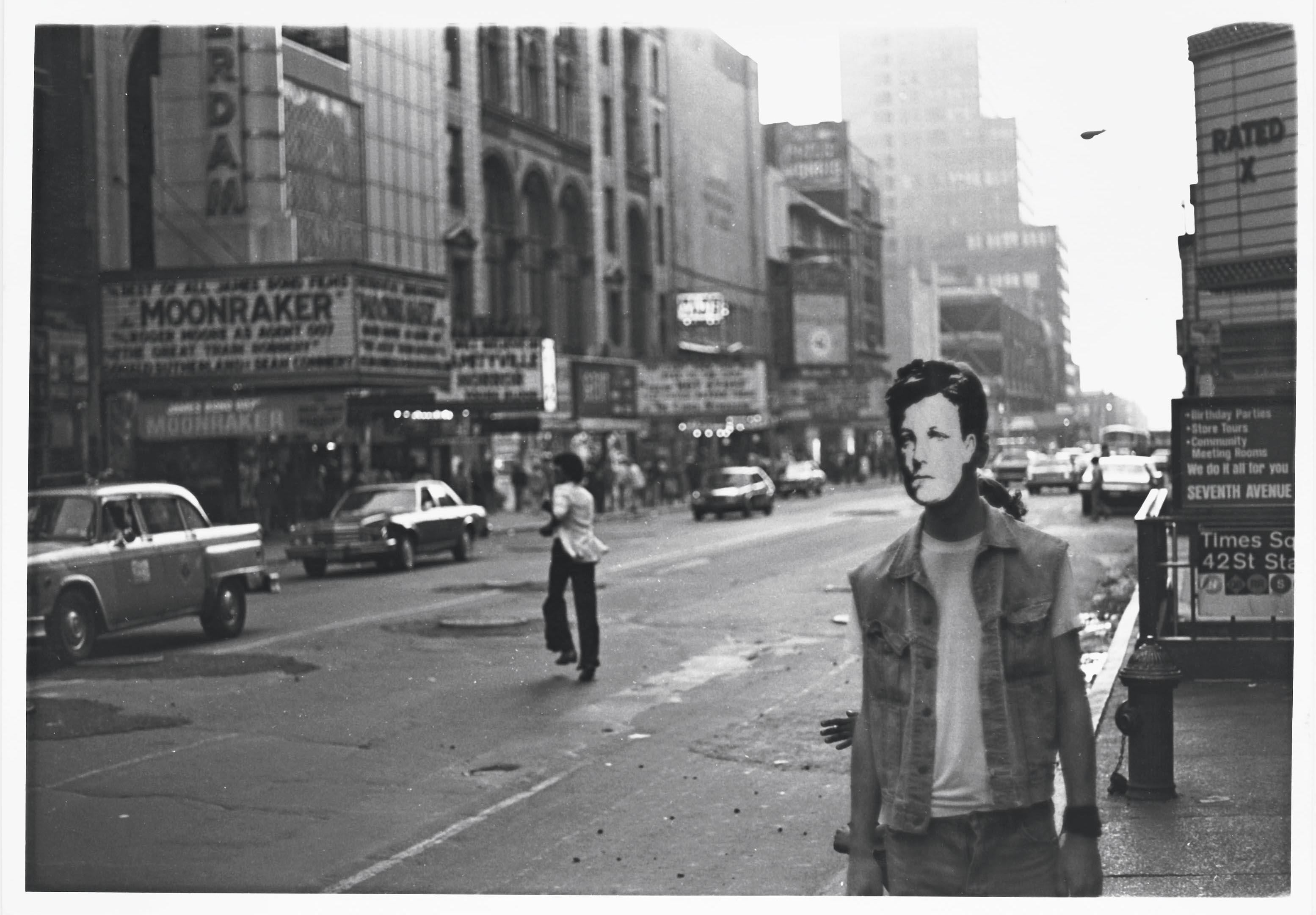

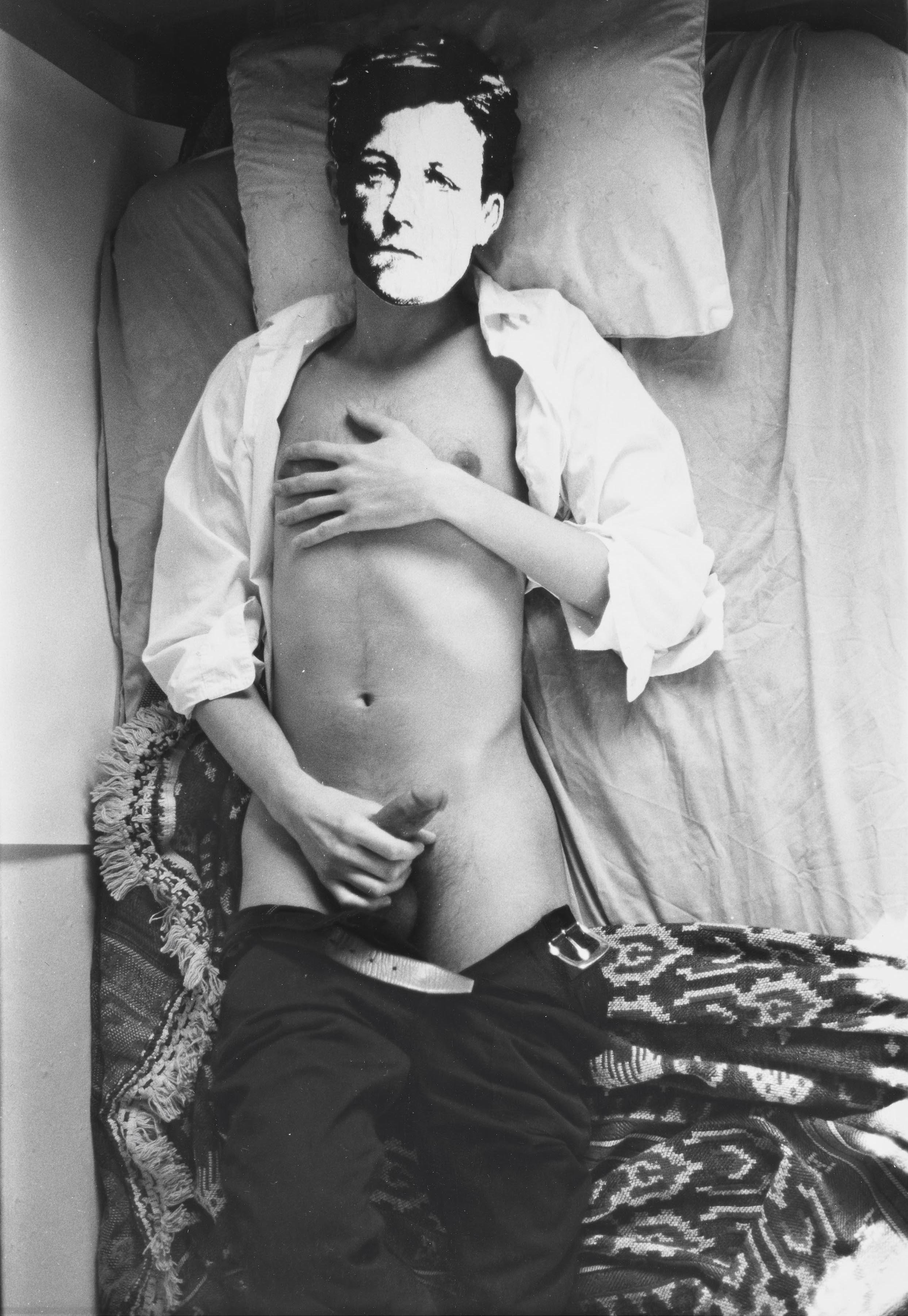

In one of David Wojnarowicz’s most famous images, he shows himself as a young boy, superimposed on two columns of text. He stares at us lankily from the middle of the page, with the oversized ears and slight buck-teeth of youth, puppy-soft eyes, tiny snub nose. The bold sans-serif contrasts with the grainy warmth of the image—a primary school photo, posed yet vulnerable. The boy is all of us as children—shy smile, buttoned-up shirt. The text reads: “One day this kid will do something that causes men who wear the uniforms of priests and rabbis, men who inhabit certain stone buildings, to call for his death. […] He will be subject to loss of home, civil rights, jobs, and all conceivable freedoms.” Untitled (One Day This Kid…) is Wojnarowicz’s indictment of how the places of power rob gay people of the simple joy of existence at every turn.

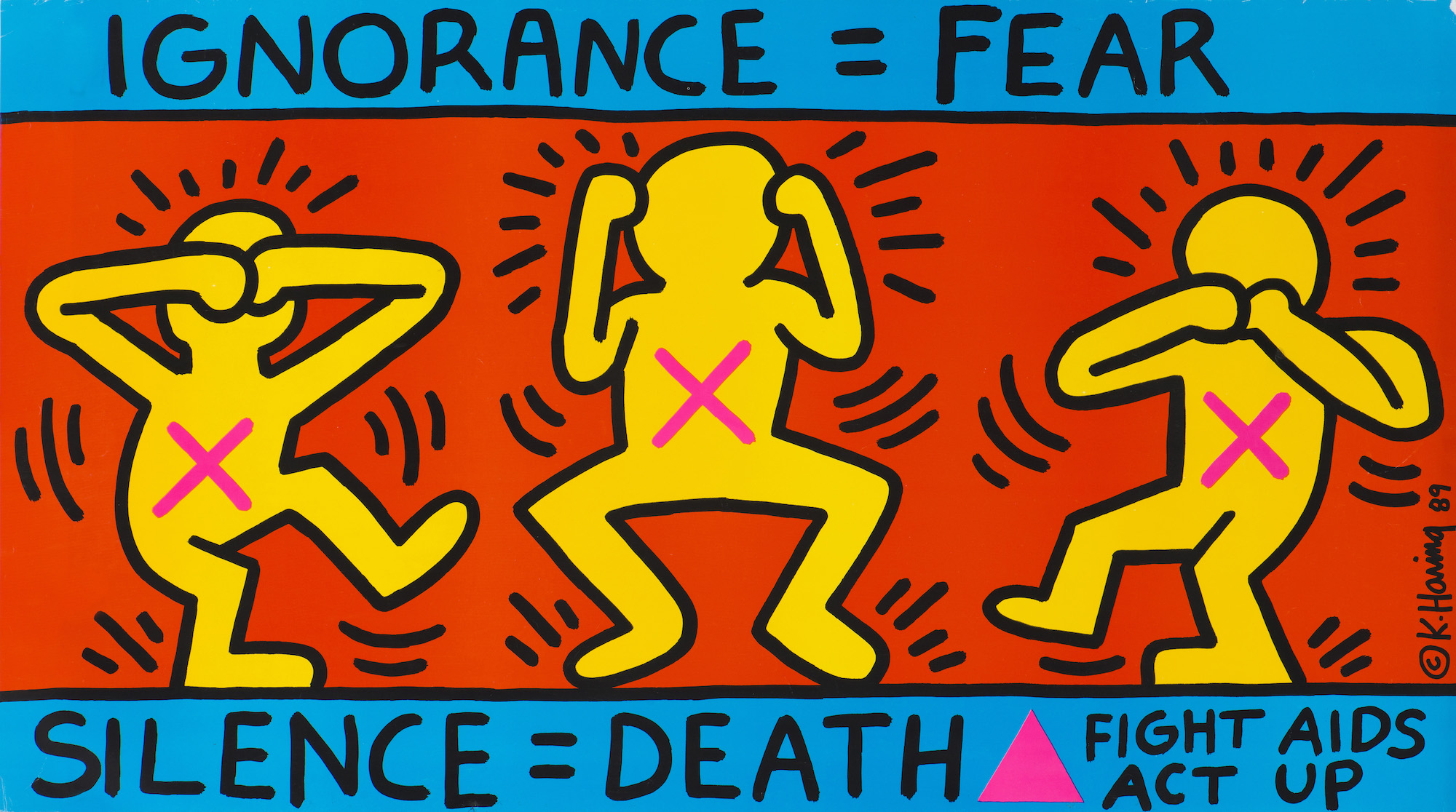

A law prohibiting the “promotion” of homosexuality in art that had received federal funding passed in 1988. “We have got to call a spade a spade,” Senator Helms said, “and a perverted human being a perverted human being.” One of the reasons Aids ravaged the gay community to the extent that it did—the inescapable scale of the horror that saw gay men watch their lovers, brothers and friends die around them—was down to concerted efforts by those in power who equated raising awareness of the crisis with promoting queerness. It’s tempting to think that the art world would take a more liberal approach, that the work of some of the most celebrated artists of the era would championed, rather than censured. But the complex web of funding processes, internal politics and conservative board members ensured that openly gay artists who challenged heteronormative ideals were denied resources and platforms to display their art, no matter their stature in the industry.

In 1989, New York gallery Artists Space hosted Against Our Vanishing, a group show curated by Wojnarowicz’s friend and fellow artist, Nan Goldin. In response to Wojnarowicz’s contribution to the catalogue, an essay that accused Cardinal O’Connor of keeping sex education messages from public spaces and thus directly contributing to the Aids epidemic, the National Endowment for the Arts threatened to withdraw their funding for the show. Eventually, the NEA struck a deal on the basis that the catalogue containing the essay would not receive any funding.

Wojnarowicz did not attend the show. He said, “I don’t feel that civil or constitutional rights are a worthy trade for money.” In 2010, almost twenty years after he had died of Aids-related causes, a display of Wojnarowicz’s A Fire in My Belly—a short film in which ants swarm like a flowing, shining sea, over a crucifix—was removed from the National Portrait Gallery in Washington DC after the threat of reduced federal funding.

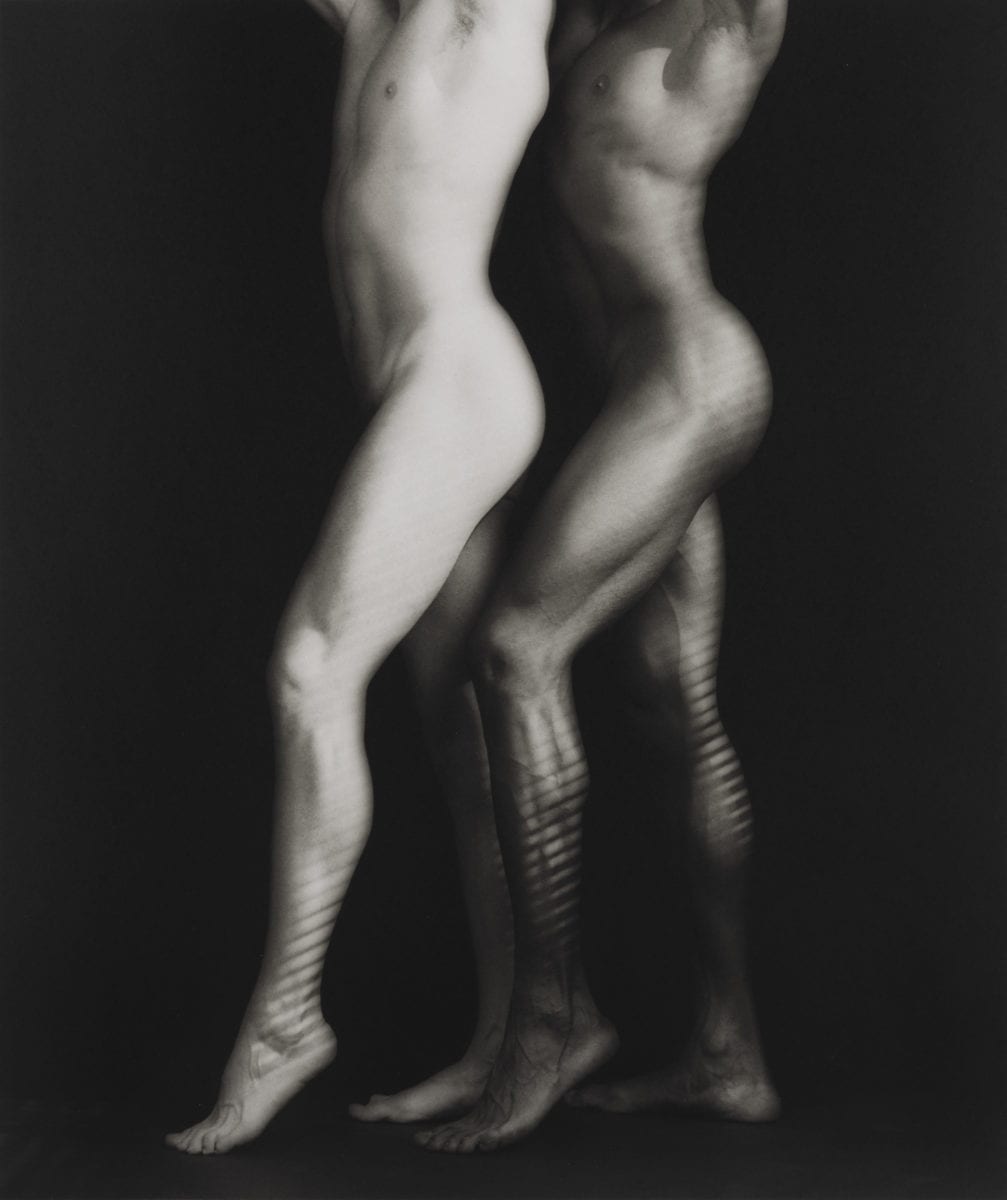

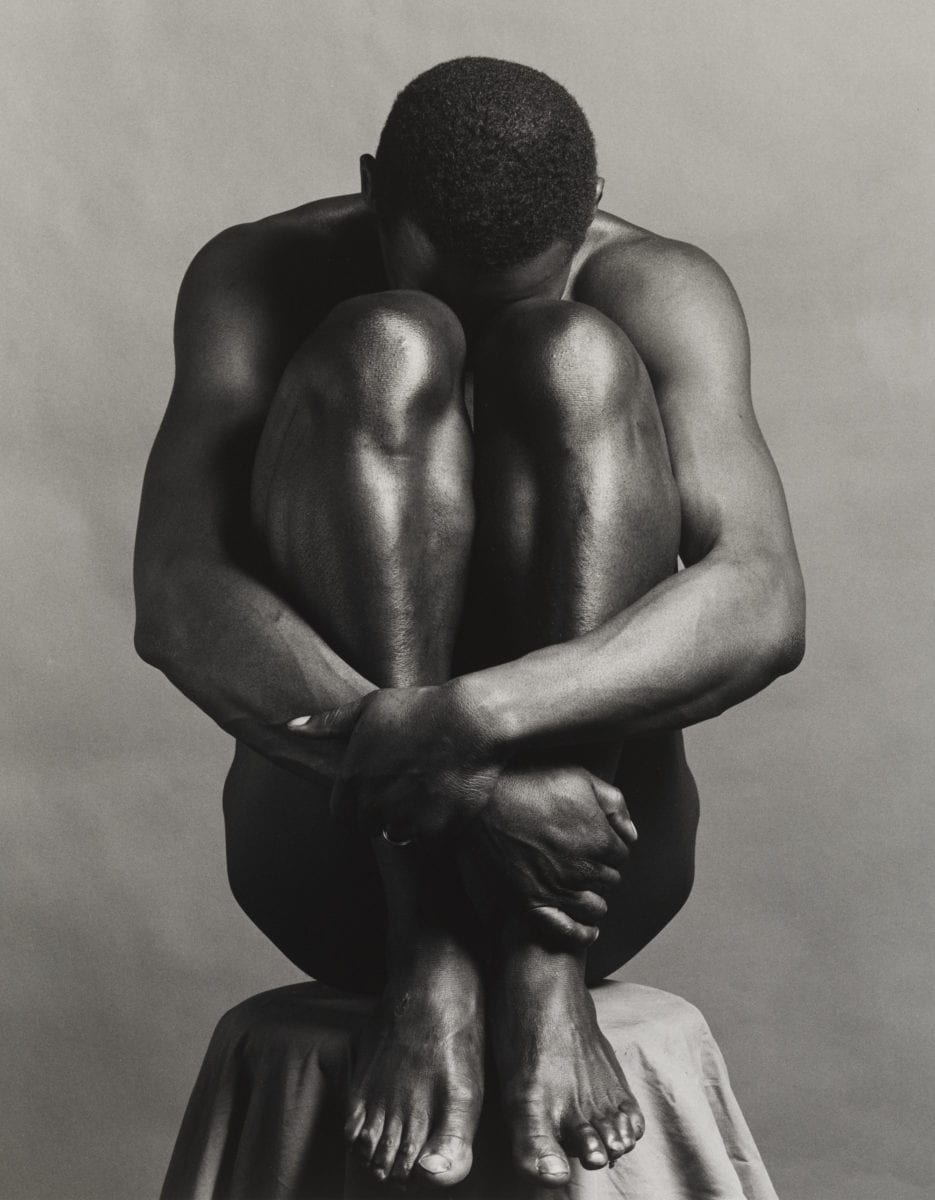

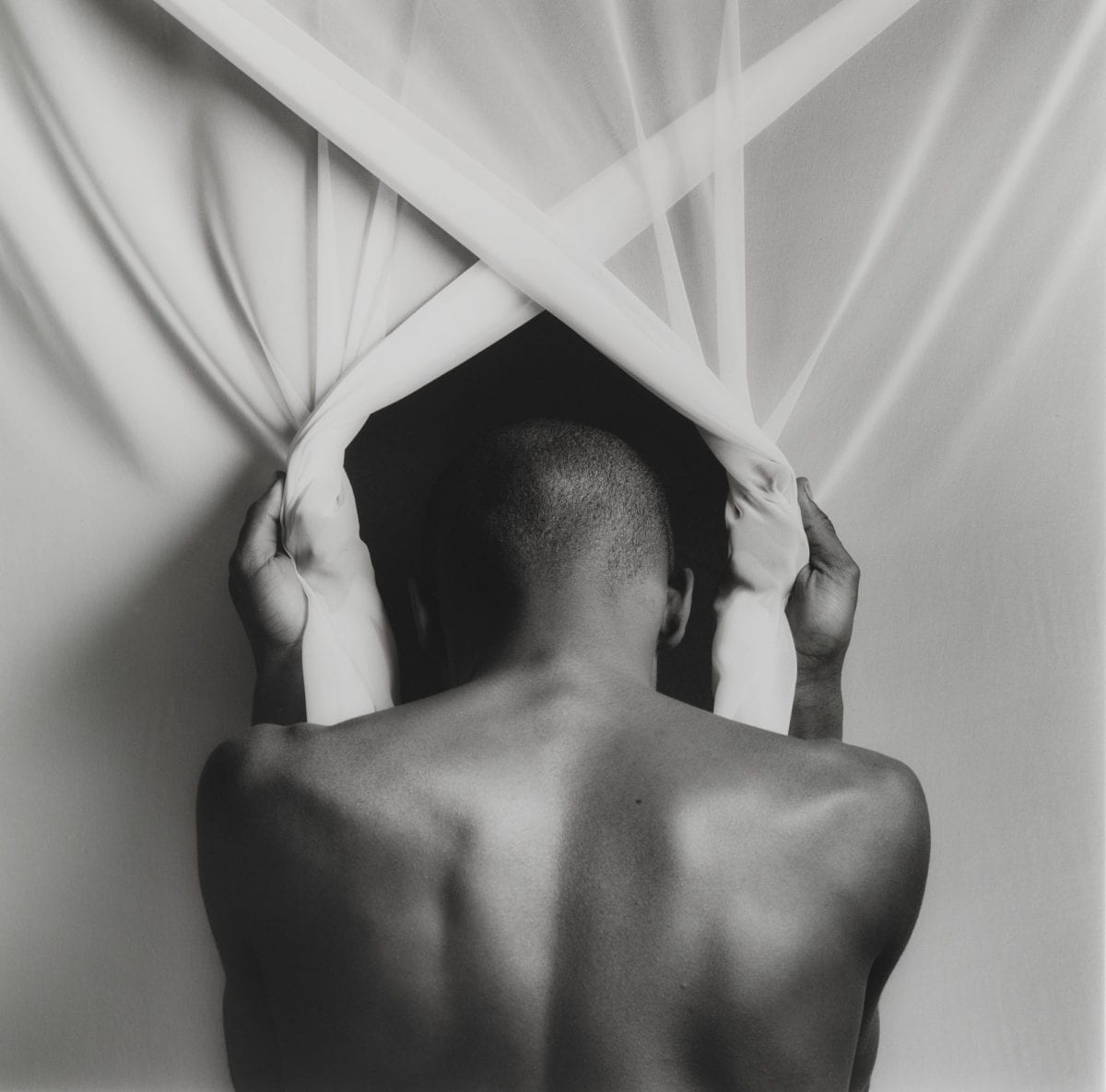

That same year in 1989, Robert Mapplethorpe‘s touring exhibition, The Perfect Moment, was due to show at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in DC. It was only months after his death from complications arising from Aids. After seeing the works—and particularly concerned about the gay and fetish elements—the gallery cancelled the exhibition. A year later, the Contemporary Arts Center in Cincinnati and its director were charged with obscenity for exhibiting the works. They were later acquitted.

“The strange circumstances of our present social climate lend themselves well to these restagings”

It seems particularly gratifying, then, that recent retrospectives of artists such as Wojnarowicz at the Whitney, Mapplethorpe at the Guggenheim, Jarman at the Irish Museum of Modern Art and Haring at Tate Liverpool have emerged as blockbuster exhibitions. The strange circumstances of our present social climate lend themselves well to these restagings: LGBTQ rights are more advanced than they’ve ever been, accepted more widely in both a legal and societal context; HIV/Aids, once an effective death sentence, has been transformed through medical innovation and public health campaigns into a manageable and treatable illness, with the increasingly widespread availability of PrEP allowing gay men to live without the omnipresent spectre of the disease.

It’s also a period of increased conservatism, with cuts to both the arts and social programmes affecting LGBTQ people happening on both sides of the Atlantic. There is a growing far-right presence and increased instances of hate-crimes against LGBTQ people, particularly trans and gender non-conforming people.

With these complex circumstances as a backdrop, it’s fitting that we would turn to artists who also navigated extreme periods of social change for advice, interpretation and analysis of our current situation. In an essay on the Wojnarowicz show, Apollo magazine intoned that his “art is as urgent now as it was in the 1980s […] It feels absolutely of the present moment.”

Jarman and Wojnarowicz’s writing, long out of print, has recently been reissued with introductions by award-winning writers, freed from the constriction of “art-writing” to be marketed towards a wider audience. Nineteen years after the creation of (One Day This Kid…), it finally feels like the future that seemed so concrete for child-Wojnarowicz is no longer immutable; that there is hope, acceptance, even celebration waiting for him.

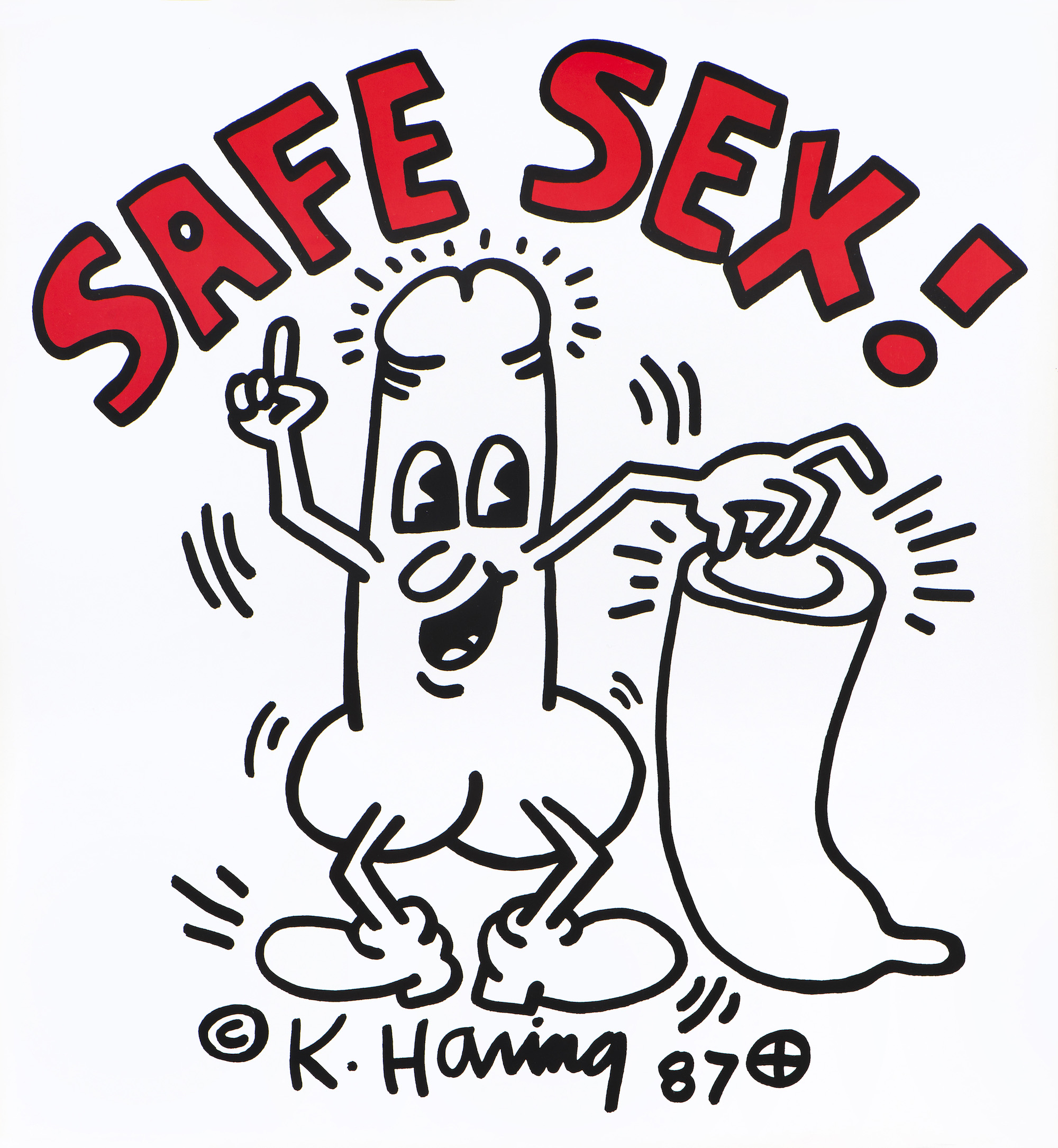

- Keith Haring, Untitled, 1983. © Keith Haring Foundation

- Keith Haring, Untitled, 1983. © Keith Haring Foundation

But as welcome as these headline exhibitions may be, there remains something that feels, if not off-putting, then not-quite-right about the desire of these major institutions to include these artists. While Wojnarowicz at the Whitney has received praise, the exhibition also drew protests by members of ACT UP (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power), the hugely influential Aids activist movement Wojnarowicz himself was a vital component of. The group accused the Whitney of historicizing the Aids crisis, and their choice to focus on the disease in the past rather than addressing the impact it continues to have. Frieze also criticized the Whitney’s handling of the subject; with a piece titled “Why Has the Whitney Tried to Sanitize David Wojnarowicz?” Following the protests, the museum added an adhesive label acknowledging the group’s ongoing contributions.

The Whitney controversy suggests that the reason for these retrospectives is not to present accurate representations of the artists, but rather to smooth them over; to sand the edges down and fill in the cracks where the true radicality of their work is exposed. On Mapplethorpe’s output, Architectural Digest noted that “In October 2017, an auction record was set as his Self-Portrait 1988 sold for around $700,000 in London […] a million-dollar Mapplethorpe is right around the corner.” Are these exhibitions genuine celebrations of the contributions of artists whose lives were taken too early? Or is their function to make gay artists more palatable to the art market, so that their works might fetch larger sums at auction?

“Are these exhibitions genuine celebrations? Or is their function to make gay artists more palatable to the art market?”

It is rare for major galleries with international reputations to take risks. Are they merely banking on the pre-established audiences of the artists that they’re featuring? Despite—and sometimes because of—the censorship of the seminal eighties gay artists, Wojnarowicz, Mapplethorpe, Haring and Jarman are now close to being household names, with their untimely deaths allowing for an almost mythological status around their work. These institutions have not fought the status quo; rather, they are now recognizing artists who have already become part of the artistic canon.

It is also important to note that Jarman, Wojnarowicz, Haring and Mapplethorpe were all white, all cis and all men. In a recent talk at London’s ICA, queer artist and performer Travis Alabanza discussed how difficult it is for queer people of colour to break into the arts. In a system that frequently allows space for only one person from a marginalized background to be featured in the gallery system at a time, there is little room allowed for greater change. Where are the major exhibitions for artists such as Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings, Evan Ifekoya and Wu Tsang? It seems as though nurturing the future of queer art, and letting go of the conservatism that saw exhibitions be cancelled in the 1980s, may still be too radical for 2019.

![Keith Haring, Untitled 1983 [X74582]](https://elephant.art/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Keith-Haring-Untitled-1983-X74582-1200x1183.jpg)