Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou talks to artist Soufiane Ababri about his current exhibition in the Barbican’s ‘Curve’ and what it means to be a queer artist with intersecting identities. For a second important perspective, she also brings into the conversation curator of the show, Raúl Muñoz.

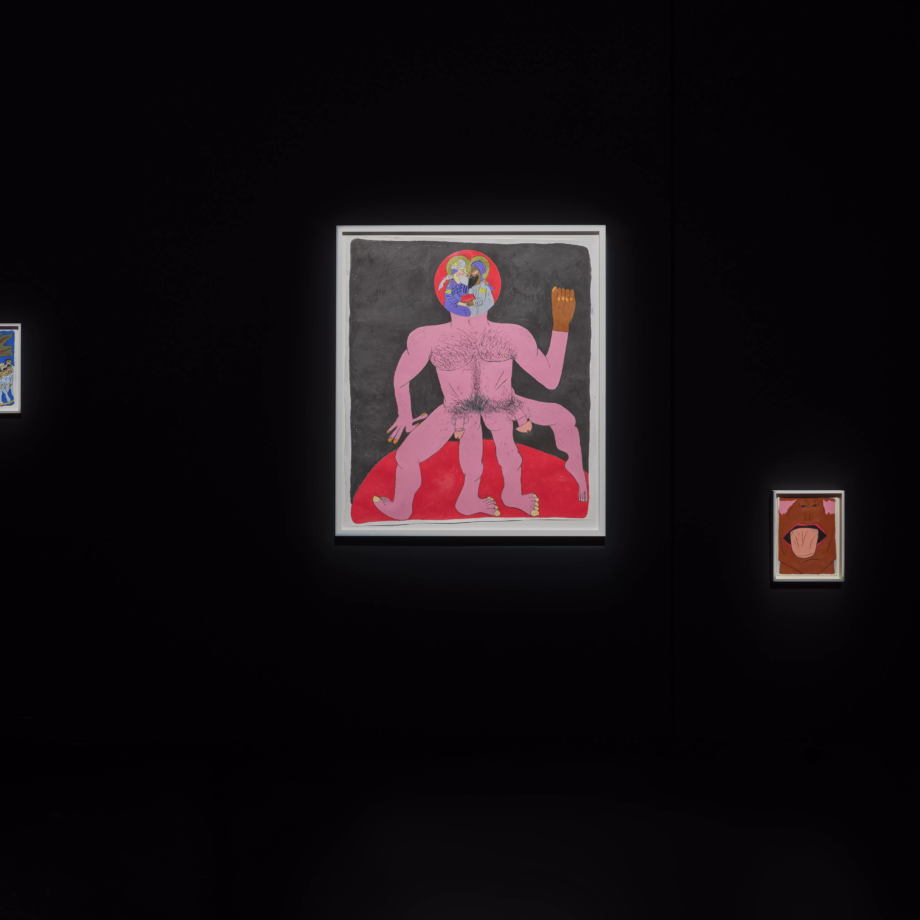

It’s been a while since I went to a club. More often than not I’m transported to the hazy, beat-infused atmosphere of such spaces by reading the accounts of other clubbers and ravers, writers and theorists. But in Soufiane Ababri’s latest exhibition, Their mouths were full of bumblebees but it was me who was pollinated, the queer night scene is recreated in all its sensuous and somewhat secretive glory. Walking along the Curve Gallery—a sloping crescent of a space that was initially deemed surplus and unnecessary to the main architectural blueprint of the Barbican—I was struck by the sights, signs and sounds one would usually encounter in former queer clubs original to the likes of, say, Kings Cross, Soho and Hackney: fog mysteriously hung in the air, metal chains kinkily linked ceiling to floor; red walls and surfaces surreptitiously appeared in the dense darkness, whilst a thick score slowly intensified along the snaking circumference of the Curve. Of course, this was no ordinary club, not least because the main clubbers were brightly hand-drawn figures, buff, often naked and boldly beautiful, but two-dimensional nonetheless. Rather, this exhibition-cum-rave experience travelled across time zones and borders, geographies and mythologies. Ababri’s interactive and transformative exhibition moves along a trans-historical axis (trans also being the operative word), one which may begin in the present but lands us marvelously in the past.

Moving along a red strip that skirts the curving parameter of the gallery, viewers and revelers alike tread the literal thin line between stigma and celebration, shame and sensuality, blood and passion. In Their mouths were full of bumblebees, red encompasses the queer historical experience. That is, the colour embraces both the liberating and exciting possibilities of what it is to be queer today as well as the persecution it still entails. There is an additional aspect to this red path—with all its cultural and socio-political connotations—that Ababri harnesses brilliantly in the shape of the space. Forming the Arabic letter Zayin—which is the first letter of the word ‘zamel’, a derogatory term used to harass gay men in the Maghreb—the path situates the viewer-raver in the language of homophobia as well as the active resistance of such verbal and physical violence. That ‘zamel’ derives from ‘zamil’, a term meaning close friend, further complicates the space and realities it recreates. The red path, as a literal and symbolic demarcation, becomes then a pilgrimage towards queer zones of pleasure and power, a timeline to those who have both been subject to and resisted such slurs. In this, the susurrating sound of ‘zzzz’ from ‘zamel’, which is hinted at by the bumblebees in the show’s title, becomes one of harassment but also pleasure; the sibilant enunciation of sensual intimacy and soothing delight amongst and between friends, which is granted by its original word: ‘zamil’.

But Their mouths were full of bumblebees is also a window into the bodily joys, discoveries and activities of queer men of colour across their diasporic communities—bodily, being how men physically dwell together and alone, interact and connect literally and across time. Traversing the red line, we espy historical figures and episodes that make up a queer chronology, archive and passage/passing of time: two men hang out, lounging on a bed amidst a pink plush carpeted room reading Palestinian literature; a bloody raid occurs on a queer hot spot in North Africa; Oscar Wilde appears, in a cruciform pose, amongst voguing and partying queer men in a nightclub. Blurring the fictional with the factual, Ababri fabulously brings forth a history that challenges the homophobic and white supremacist hegemonic structures and forms that throw slander—the ‘zzz’ —and scorn on queer relations, relationships and modes of socially and sexually relating. The result is an extension of bodily and social spaces out into that of the Barbican; a red highlighting of vanishing sites and areas of being and communing, and an insistence for the ‘zamil’ over the ‘zamel’ of present homophobic politics and powers.

I had the enormous pleasure of speaking to artist Soufiane Ababri and the show’s curator Raúl Muñoz de la Vega in person and via email about all this (and more) for Elephant and learnt that healing and joy, as well as suffering and pain, exists by walking in the red zones of life.

Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou: In the Curve Gallery you physically and spatially position us within the Arabic letter Zayin. In doing so, you highlight both the marginal space concealed inside the Barbican and the linguistic journey of the derogatory term ‘zamel’ from the more nuanced word ‘zamil’. We go from looking at and processing the outer violent derision of the term ‘zamel’, to connecting with and appreciating what sits at its centre: fear of deep intimacy, particularly of the non-heteronormative kind (‘zamil’). This re-appropriation and subversion of language occurs in your art through allusions to literary and musical works, historical events and figures (most of whom are part of queer culture). Would you say the presence of these embedded references/codifications also challenges homophobic erasure, violence and suppression, whilst also creating a kind of coded queer language of intimacy and community, resistance and recollection?

Soufiane Ababri: The key for me lies in crafting a genealogy; weaving intricate connections that bring to light and legitimate shared narratives in the shaping of marginalized identities. This act of ‘laying the groundwork’ allows me to unearth fragments from both queer and colonial histories that will serve as the bedrock upon which to develop artistic projects. It’s akin to excavating the past to create works in the present that speak to a utopian queer future. However, the ostracization imposed by heteronormative culture often complicates this endeavour. Hence, my work invites all of society to witness the nuanced processes of identity formation within the queer community.

Often, people have a sibling or a child who is living, or who has lived through, some significant life events, and has navigated them silently and unbeknownst to those around them, even if they’re living under the same roof. These are narratives obscured by society’s hegemonic structures. My work is devoted to documenting these experiences which are rendered invisible by societal norms.

HHG: I love that you’re creating queer genealogies for people. This is also evident in your ‘I’m not just a faggot series’, where the likes of Wolfgang Tillmans, Roland Barthes and Frank O’Hara are depicted to further complicate and, again, re-appropriate derogative terms and notions aimed at queer men. Born out of your continued engagement with literature and philosophy, this series, too, creates a kind of encoded language of unity; a lineage of gay men and peoples through which to celebrate and commemorate queer existence and subjectivity, creativity and intimacy, and ultimately resilience. Firstly, could you discuss the influence of literary/cultural figures (Oscar Wilde, Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti etc) cited in the show. Secondly, could you talk about why it’s important for you to draw such figures together alongside the more unknown male figures in your drawing?

SA: In my practice, I often work from real-life experiences, which I then abstract into theoretical frameworks supported by extensive research. Put succinctly, my aim is to articulate the condition of a queer child who finds themselves adrift in an environment devoid of recognizable points of reference—be it within their family, at school, or even during medical encounters. However, upon venturing into spaces like libraries or bookstores, they encounter narratives that mirror their own experiences. It’s in this realization that they find the courage to embrace their identity and navigate similar paths. This queer child was once me in Rabat, Morocco.

HHG: I love this legacy: crafting a mirror for tomorrow’s generation of queer children in which to see themselves more clearly. Having said that, I wouldn’t describe your work as being overtly didactic—though it still has the capacity to educate the viewer, particularly cis het viewers, when it comes to queer sub-cultural movements, practices, communities and relationships. In light of the threat towards queer spaces and bodies (closure, attacks, violence, denial of basic human rights, criminalisation), would you say your work inadvertently creates an archive of present, as well as past, queer culture and experience? Or are you animating and challenging current archives that conceal the presence of queerness?

SA: In many ways, my work serves a dual purpose: combating the historical marginalization of queer narratives while also illustrating the intricate and intertwined nature of queer existence. I consciously steer clear of romanticizing the concept of resistance. For me, resistance is primarily a tool, one that enables both myself and my audience, the viewers, to reframe ourselves and assert our agency. It’s about empowering individuals to rewrite their narratives, especially in the face of societal pressures to adhere to predetermined, productivity-driven paths. I believe in a utopian version of friendship and sexuality and therefore my drawings reveal a society in which radical sexual practices and forms of socialization are allowed.

HHG: You’ve created this brilliant site-specific work that saturates us in red light and requires us to traverse the red (“path”) letter Zayin, thereby immersing us in the socio-political implications and cultural connotations of this colour. But there are other tones that are just as radically and subversively employed: the pink blush on men’s cheeks and orange on their feet and hands, a beautiful feminisation that you embrace across your oeuvre. Bold and bright, enticing and generously applied, the polychromatic palette in your drawings demonstrates how colour can be aesthetically pleasing and persuasive, whilst also having deep cultural signification and political purpose. (It’s very apt that Ibrahim Mahama’s pinkish purple cloth is draped across the lake-side-facing façade of the Barbican at the same time as your Curve show.) Could you talk more about the importance of colour in this show and your work in general. On the other hand, I wondered also if you felt that as a Queer artist of colour the palette you use, the work you do, gets overly politicized when sometimes your intentions lie elsewhere and you may just want to enjoy a particular hue?!

SA: My practice is inherently political, yet I find the need to critically reassess and redefine the term itself. Douglas Crimp was political, Toni Morrison was political. There’s often an expectation placed on queer Arab artists to be activists, which I find to be a coercive demand. I believe that art has the power to effect change and provoke transformation in viewers without resorting to direct action or active propaganda. Moreover, I see my artistic and political work as symbiotic processes that shape and transform me just as much as they do those who engage with my work. My starting point isn’t necessarily theoretical; rather, it springs from a desire to rewrite and reimagine myself.

From a young age, I’ve recognized that colours carry inherent meanings in art, as well as in domestic and social contexts. They are laden with meaning and impossible to keep neutral, and that is something I reflect in my work.

HHG: Going back to the figure ‘Zayin’ that we traverse, this felt to me like a transformative pilgrimage or even a form of time-travel, one where we start with the snooker cue and reversal of the balls (another challenge to the traditional values and logic ascribed to certain colours) only to then arrive at the drawing referencing Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti. Are we going back in time, in order to move forward? Is this a kind of path of pleasure as well as pain, one that delivers us to a point of connection and love by walking along/working through the trouble and trauma of homophobia?

SA: I think that’s a fair assessment. Indeed, José Esteban Muñoz’s concept of turning towards what Bloch terms the “not-yet-conscious” resonates deeply with me. As Muñoz articulates in Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (2009, NYU Press), this shift is a necessary precursor to realizing the “not-yet-happened.” For me, creating artworks that recover elements from the past, from history, and using them as lenses to critique the present serves as a driving force to make meaningful change in the future.

HHG: Raúl, there are so many different forms of intimacy visualised and explored in this show. I love that Soufiane demonstrates how desire, love and friendship can be experienced and related in diverse ways. Firstly, nudity is a point of intimacy; the exposed tongue another; two couples simply listening to music or voguing together are other examples. I cherish and enjoy them all—which is another form of intimacy he’s building between his works and the viewers. Then, of course, the whole show is situated in a kind of recreated queer club/space, which fosters a socialised form of intimacy. I wondered if this was also the point you both wanted to make: that queer intimacy is at once inflected by the socio-political sphere but also supersedes it, thereby overriding its regulations and repression? Is the show designed to foster new dwelling spaces for this intimacy and care to flourish? I certainly wanted to dwell with it and felt kinship with Soufiane’s works and how you curated them.

Raúl Muñoz de la Vega: I concur with your initial observation. One of the pivotal references for the show is an interview Foucault gave late in his life (‘Friendship as a way of life’) where he elaborates on how homosexuality opens the possibility for men to explore a new emotional landscape that—exempted from the impositions of hetero-normativity – generates radical forms of friendship. In this sense queer clubs have functioned as one of those spaces where a new reconfiguration of relationships could be tested.

McKenzie Wark is interested in raving as a collaborative practice that makes it possible for some people to endure life (see Raving, 2023, Duke University Press), and the show certainly looks at that deep meaning of nightlife and rave culture for the LGBT+ community. However, as you pointed out, while we appropriate the visual codes of nightclubs and raves in the exhibition, along the space the letter zayin unfolds as a sort of corridor of shame. We harness that duality to initiate a dialogue about the impact of stigma on marginalized communities, exploring the restoration of dignity through collective action and the potential of marginality as a space for transformation.

HHG: Beautifully put. The potential of marginalized space and forms also brings us to Soufiane’s decision to put drawing at the forefront of his practice. Drawing has been feminised across the ages, derided as a domestic, preliminary form and in this derogation and derision, I think, lies its power as a primary tool, mode, process and art form. Raúl, could you talk to me specifically about drawing; about the process, about its edges and its (liberatory) potential?

RMV: I find that Soufiane’s opting for drawing as his primary medium aligns with his extensive exploration of marginality and its capacity for transformation. This theme isn’t only a subject matter in his work but permeates his entire artistic process. By selecting drawing— or using wax pencils—over more recognized mediums like painting or sculpture, he not only challenges the traditional undervaluation associated with drawing but also creates an opportunity to disrupt established artistic norms.

HHG: As a segue from this question, could we speak about Soufiane’s stunning “bedwork” series and working from the bed or a reclining position. I love this! I work from bed too, mainly because of health, but also as a form of comfort when the world gets too much. I know for Soufiane it is an anticolonial process and a politically pertinent position to occupy (speaking back to the orientalist gaze, to western subordination and its othering of Black and brown individuals). But there’s also this generosity of intimacy again; of Soufiane gifting us with art from a deeply personal place and even inviting us into his bed? Would you say this is so?

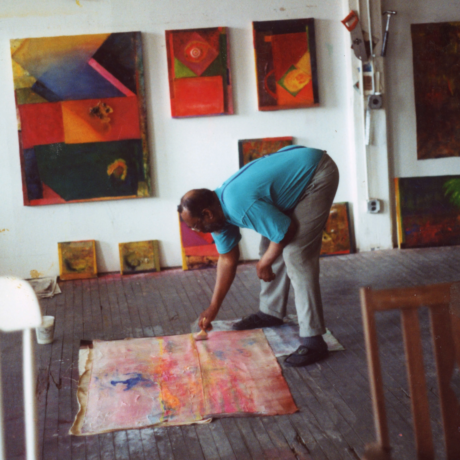

RMV: When Soufiane studied art, he realised certain racialized bodies were always depicted horizontally. There was always a hierarchical approach between something vertical and horizontal, between the painter and subject. He wanted to reverse that in his practice, so he decided to work horizontally, from the position that is usually disempowering or given to the disempowered. He’s always trying to give back dignity and agency to those bodies. Working from the bed or from a horizontal position also touches on the rhythm imposed on us; when you’re in bed for a while, this rhythm alters.

HHG: Soufiane, this may seem slightly off topic but I wanted to talk about the burden of care in your work. There is such care in the rendering of the figures, the scenarios in which they find themselves, their gestures, the tableau or congregation of bodies. There is extreme care in the execution of your drawings but in the curation of it too. Is this care-work—for suppressed stories and experiences, for marginal individuals and bodies – left too much to queer artists of colour? Is there a small hope implied in the final work – an embrace between two men, a hybrid body—for us all to care a bit more, queer or otherwise, and share this load?

SA: Certainly, my artistic practice is anchored in hope, or to be more radical, on a utopian ideal in social interaction. Reflecting on my own experiences upon arriving in France, I found glimpses of this utopian vision in certain spaces where radical forms of socialization were possible. However, I believe that the true peril lies not only in patriarchal dominance but also in the restrictive ideologies propagated by certain segments within both the LGBT+ and conservative feminist movements.

HHG: Raúl, another radical form of socialization occurs across Soufiane’s work in the form of performance. I know this exhibition involves specially commissioned performances—and that he has created performances for exhibitions before. But his figures also perform: whether that be dancing together or alone, caressing and listening to each other, in the act of love-making and hanging out, or simply in the vibrant insistence of their representation. There is a performative, though no less profound, element to it all. What draws him to spectacle and performance and the inherent rituals behind both? And would you say audiences get to the political or erotic quicker through a curated performance or sense of performativity in an artwork?

RMV: In Soufiane’s artistic practice, drawing, performance, installation, and scenography converge to form a cohesive body of work, with each medium providing a new lens to explore a theme. In Their mouths were full of bumblebees but it was me who was pollinated, a good example of this is ‘L’Ambuscade’ (The Ambush). The drawing depicts a raid in the fictional Zayin Club, with the identities of the assailants concealed. This drawing initiates a dialogue with the exhibition space itself, as visitors inhabit that fictional club as they go through the exhibition, while also resonating with the performance where a group is not allowed to enter the club. Through this interplay, the work explores various facets of how stigma impacts marginalized communities reflecting on the possible avenues for its subversion.

HHG: Speaking of subversion, I wondered if Soufiane could talk about escape and fugitivity. That is, some figures escape through drugs, through dance, through other men. But language is arrant and fugitive in this show, beginning in one place and ending in another, literally. Would you say these metaphorical acts and flights of escape are important right now?

SA: Certainly, escape is a central theme in my work, and I draw inspiration from Édouard Louis’ exploration of this concept. I view fleeing as an act of immense courage and resilience, especially in the face of violence and oppression. For individuals marginalized due to their gender, sexual orientation or other identities, leaving behind everything they’ve known – often without security or resources – is an incredibly daunting task. A journey of self-reconstruction often begins with escape, manifested in various forms. However, I find it crucial to emphasize that true escape does not entail turning to drugs or other harmful coping mechanisms.

HHG: Lastly and simply, but no less importantly, are you working on anything new that we could hear about or are you having a well-earned rest? And will the show tour or will parts become part of something new?

SA: There are plans for solo exhibitions in 2025, but also two books coming out soon, one on the Yes I Am series (AKA Faggot series) that I’m publishing with Triangle Books, and one which is volume 1 of a series of sketchbooks I’m publishing with XXX, a publishing house in Morocco.

Soufiane Ababri: Their mouths were full of bumblebees but it was me who was pollinated is showing at The Curve, Barbican Centre, until 30 June 2024, with specially commissioned performances on June 30th.

Words by Hannah Hutchings-Georgiou