Taking inspiration from the Sci-Fi writings of authors such as Stanislaw Lem, Qwaypurlake at Somerset’s Hauser & Wirth reimagines the landscape in a world ‘where humans have been marginalised, or even expelled, and the landscape is dominated almost entirely by water’. Here, Curator Simon Morrissey discusses his childhood fascination with sci-fi, the etymology of Somerset and the nature of curation.

When I was growing up in South Wales in the 70s & 80s art wasn’t something that was particularly part of my experience. Like lots of British kids, television, film and later music was a much more tangible place for me to find the expression of ideas and emotion than art or literature.

I remember that when I was maybe around 11 or 12 my parents set me the task of reading ten books over one summer. I wasn’t much of a reader at that age and my father promised £10 for each book I read. I can’t remember if I encountered science fiction at that precise moment but I became an avid reader in my teenage years following this challenge and classic speculative fiction such as the books of John Wyndham became a real enthusiasm. Authors like Wyndham imagined other-worldly occurrences with often-dystopian results but rooted them in the world as you experienced it as a reader – strange children with telepathic powers aggressively taking over a sleepy village in The Midwich Cuckoos; carnivorous plants stalking an ordinary England populated mainly by blind people in The Day of the Triffids

. Apocalypses on streets like the ones you walked to school on.

Art was something that started to nag at me in the later stages of comprehensive school. I don’t think I was ever particularly good at making it but it captivated me — staring at Rothko paintings in books and wondering what they meant. As a teenager I was obsessed with music, but lunchtimes at school would also consist of disappearing with my two best friends to the school ceramics room. We would make pottery whilst playing Beastie Boys and The Fall on a battered tape deck. I discovered seminal German ceramicist Hans Coper listening to mix tapes of music ripped off the John Peel show.

I didn’t have a formal curatorial or art school training, but started working for galleries after leaving University with the desire to be a curator without fully understanding what that meant apart from that you ‘made’ exhibitions. I began writing a lot about artists and exhibitions for magazines and it was through formulating ideas for features to pitch to editors that I first started to think about using devices that a fiction writer might use to create structures to investigate the relationship between artworks, or even imaginatively reframe them.

Reading fiction led to using fiction as a device in critical writing, which in turn led to thinking about how that approach might allow me to play with the idea of building narrative conceits for the first exhibitions I curated back in 1999. The idea grew of weaving artworks together to suggest a fictional frame beyond their separate concerns.

Qwaypurlake is, similarly, an exhibition as curatorial fiction. It takes elements of Somerset’s history and influences from classics of speculative fiction, such as Stanislaw Lem’s Solaris

, to imagine an alternative reality (or a possible future) for Somerset where human presence has been marginalized, or even expelled, and the landscape is aggressively dominated by water.

Somerset’s name derives from a number of references to the fact that in the past large elements of the county were regularly subsumed by water. In the Welsh and Cornish languages Somerset is called by names that mean ‘Country of the Summer’, which reference the fact that the county would flood significantly and only be accessible in Summer. Somerset’s name is also claimed to be a derivative of the old English ‘Seo-mere-saeten’ meaning ‘settlers by the sea lakes’, which again emphasizes the way Somerset’s coastal relationship was expanded through an inter-zone of flooded plains.

The exhibition’s title derives from the name of the road, Quaperlake Street, that leads between Bruton, where Hauser & Wirth is located, and the town Frome, where I have lived for the past 13 years after moving from London. The name has always intrigued me — it is not a word with an easily locatable meaning. Its origin may derive from Huguenot French settlers to the area in the sixteenth century and be bastardised from the French ‘by the lake’ — but whatever lake this may have referenced is now absent and the reference dislocated. The odd quality of the name planted a seed in my head of curating a project that would overlay the Somerset countryside with its own science fiction.

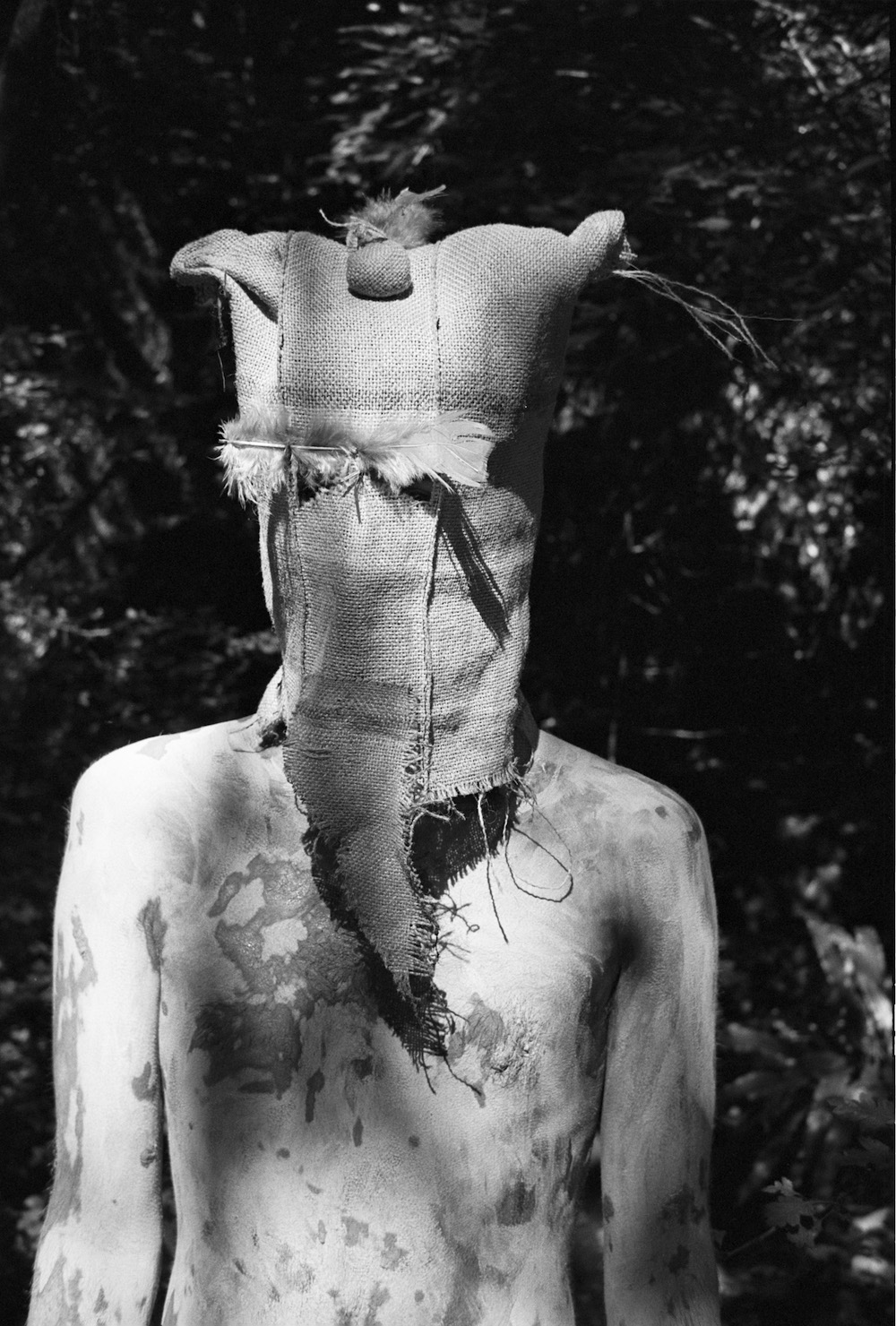

This fiction is woven around the work in Qwaypurlake but is also built out of the artworks themselves. There is the implication through key works in the exhibition, such as David Wojtowycz’s film The Lake

and Alex Baker & Kit Poulson’s Transmitters, which both emit sounds that border on communication, that this water is sentient, or conscious. The exhibition is then curated to suggest that this has in turn formed the material culture of a marginalized human presence that half fears and half worships this alien, intelligent force.

The exhibition brings together twentieth century figures such as my teenage pottery room hero Hans Coper (who ended his days living in Frome), to Cornish painter Peter Lanyon (who died in a glider accident outside of Taunton in Somerset), to some of my favourite contemporary artists such as Michael Dean and Heather & Ivan Morison. The exhibition also brings together very different types of work, from documentary photography to abstract sculpture, but all of the works perform very particular roles in the exhibition with regard to fabricating the fiction of the Qwaypurlake as an entity and the human relationship to it.

The exhibition is in many ways a collaborative exercise in extrapolation and reframing: ideas are drawn out of artists’ work, discussed with other artists, woven between works to change the way in which we would expect that work to be interpreted. Ideas are taken from history or speculative fiction and imposed over works to achieve the same end; artworks are installed together to create a composite tableau that the viewer moves through like the protagonist in a film scene; a short story is constructed for the publication from collaged fragments of my own and the artists’ writings.

The act of curating is now part of a well-established critical and academic dialogue but it is still a discussion limited in many ways by ideas of institutional history and implied hierarchies of interpretation of art objects. Is it a practice or a profession? An act of communicating meanings defined for art by artists? A stimulation in the exchange between art objects and the many ways that objects can be framed in the world of ideas? Or a separate creative endeavor?

There are still fundamental questions to be asked about the parameters of what it is it that curators are allowed, or allow ourselves, to do and what is at stake for artists and audiences in questioning codes of curatorial behaviour. I hope Qwaypurlake is part of that discussion.

Qwaypurlake is showing at Hauser & Wirth, Somerset until 31 January 2016