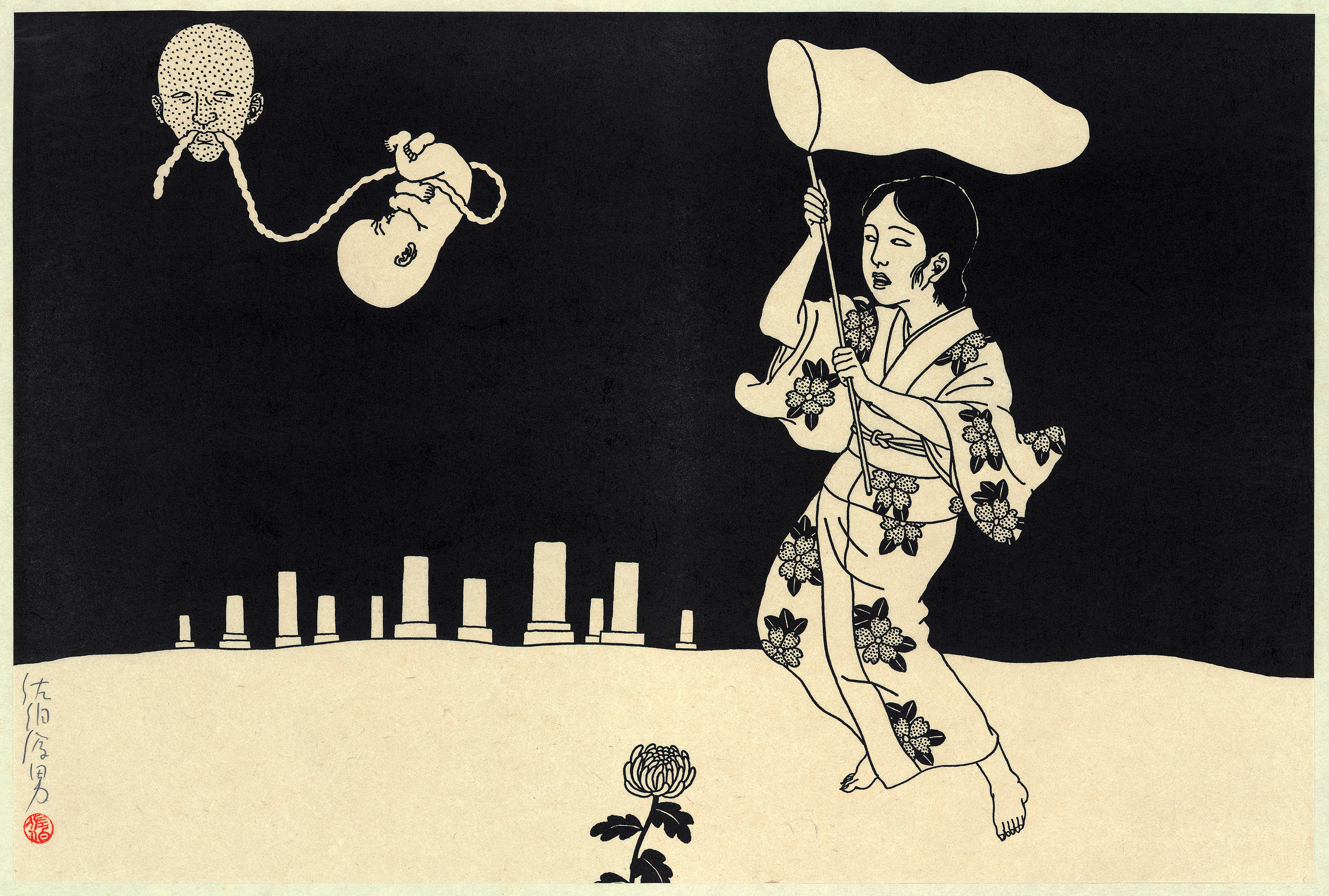

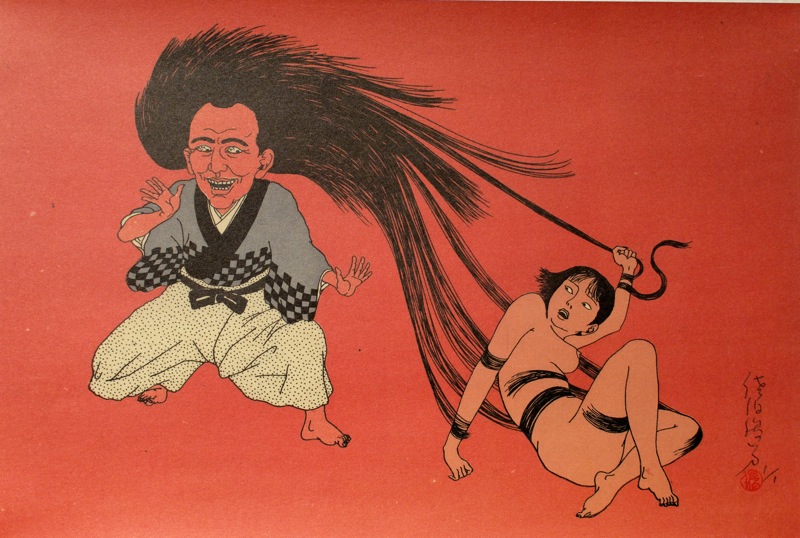

Ureshidaruma, from Red Box

You never forget a Toshio Saeki work once you’ve seen one. It’s not just the images—and there are absolutely no boundaries when it comes to what he depicted in his art—it’s their atmosphere. Strangely quiet, nocturnal, elegiac. There’s a mischievousness about them that, even when looking at the most horrific scenes (incest, bestiality, murder, you name it) you don’t want to look away—unlike the way I sometimes do with, say, an Araki photograph (Araki is a contemporary of Saeki, though the two weren’t friends). When Saeki passed away in November, he left a lot of questioned unanswered about his work: what he drew, and why.

I spent two months interviewing him, and some of the people who worked with him closely, friends he used to drink with in the tiny watering holes of the Golden Gai (I even met a barmaid that used to serve him in the 70s). But as a westerner especially, there is a lot you just can’t get your head around. Even when I asked the man himself, for example, why he drew schoolchildren into these sex scenes, he seemed confused—and unphased—by the implications.

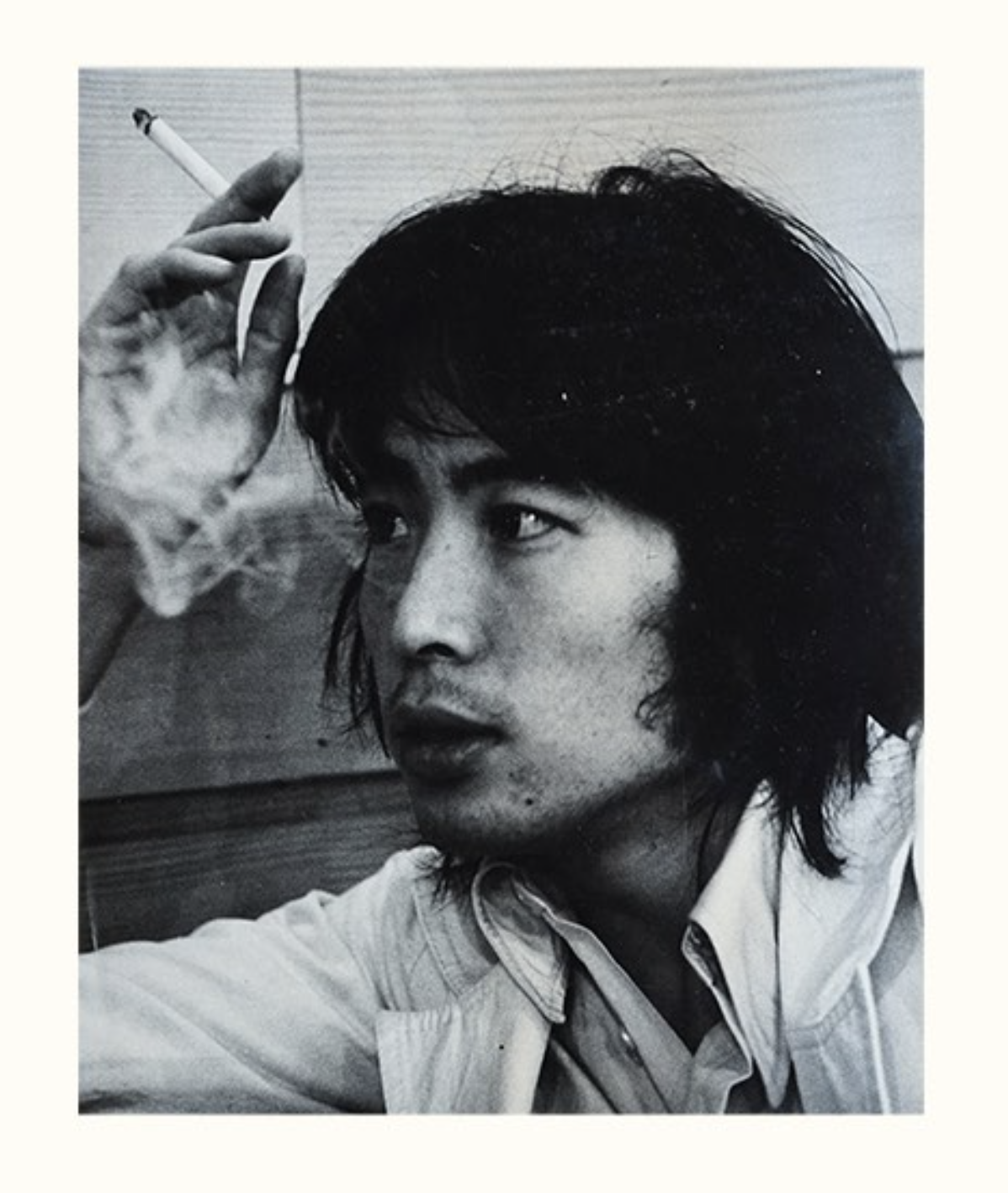

Saeki was an entirely unique artist, and unsurprisingly, an entirely unique person. The night before I first traveled to meet him, I had nightmares, imagining a cruel, belligerent drunk, fierce and unforgiving. We had strict instructions to be at his studio, about an hour’s drive from Tokyo, by 6am, to begin the interview. His health hadn’t been good and we found him frail, emaciated and unable to stand, Yet he was still extremely hospitable, generous and lucid, shy but cracking jokes.

It was the first of many visits, for hours at a time. What struck me most about Saeki was how close to Nirvana he seemed; having left Tokyo and it’s booming economy in the mid-1980s he lived simply, humbly and without desires other than to draw. Part of me, I’ll admit, wondered if there was more to this self-imposed exile. But he genuinely seemed someone who wasn’t affected by ambition, by the relentless rat race of modern life. If people liked his work, that made him happy. But he didn’t care about too much else.

For must of the last decade, Saeki has been a part of my life. I first encountered his work in 2011, and began to research it more deeply in 2012, curating an exhibition in London in 2013. The last ten years saw unprecedented interest in the work of Toshio Saeki outside Japan, his Tokyo agents observed. Most recently Saeki was part of exhibitions in Los Angeles and New York at Jeffrey Deitch’s

galleries, he started to appear at art fairs abroad with Nanzuka gallery, and the first edition of a complete five-part collection of his works was published by Éditions Cornélius.

Yet since the 1970s most of Saeki’s work was not made for public display but for hard-to-find, avant-garde publications, and as such he’s developed a cultish following, beyond the confines of the art world. Being a true artist of the underground, Saeki didn’t define his art by the spaces in which it is presented, or by the fact that no institutions ever gave him proper recognition.

“There’s a mischievousness about them that, even when looking at the most horrific scenes (incest, bestiality, murder, you name it), you don’t want to look away”

An unusual and mysterious atmosphere that shrouds Saeki, and his isolation from the world undoubtedly enabled him to produce the work that he did, free and distant—a quality that is rare in our hyper-connected age. But in his later years, he was opening up to a receptive outside world: “The reactions from the western audience in these past five years or so have been amazing, much beyond what I have experienced, and it seems to be growing,” the artist told me.

Despite Saeki’s influence in the underground scene (his first exhibition was in Paris in 1970), his work has still not received much critical investigation, either in Japan or abroad. This lack of attention is partly, of course, down to the content of his work; he digs into the darkest depths of the subconscious, creating glaringly authentic nightmare scenarios even Freud couldn’t dream up.

Saeki’s work has elicited impassioned criticism over the decades—something I encountered when, in 2013, I curated an exhibition of his prints in Dalston: the show had to be moved from the ground-floor gallery to a first-floor corridor area, or else be censored completely from public view. The works were part of the Akai Hako print series from the 70s—in fact, some of Saeki’s less extreme work. But he has created many images that beleaguered his career. His scenes, who they are for, what they represent and what they suggest are at the very limits of art versus morality. This reveals perhaps more about our society’s response to the inner turmoil of the individual—even when that turmoil is most painful to the individual himself.

The artist began to work with agents in Tokyo in the 2000s, and they have been paramount in exporting his work, determined to tackle in a more head-on manner the problem of bringing his transgressive work out into the open. “It is very radical and contains many explicit expressions. Even if critics or other people in important positions liked it, perhaps it was hard for them to come out and say it. But we feel things are changing now, and that Saeki is starting to receive the attention that he deserves. As an example, we are just now beginning to discover Saeki’s huge popularity in China, which seems to have been going on for many years,” Saeki’s agents, who prefer to remain anonymous, and keeps a low profile, told me.

“He digs into the darkest depths of the subconscious, creating glaringly authentic nightmare scenarios even Freud couldn’t dream up”

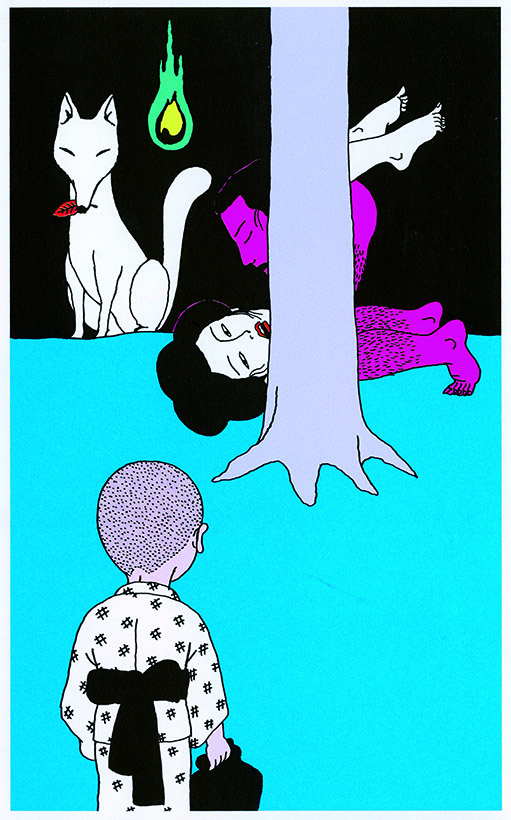

It is very important to find a context for Saeki in art history. But it won’t be easy. He could be aligned with the Ero Guro (“Erotic Gore”) movement that dates back to postwar Japan, with a second wave in the 70s. New audiences and markets looking for Ero Guro art have perhaps followed an algorithmic trail through the virtual world to Saeki. A number of museum exhibits of historic examples of Japanese erotic horror art started to introduce the roots of the movement into the public consciousness—the British Museum’s Shunga exhibition, the Met’s Japanese Exhibit and Hokusai shows at the Grand Palais, Paris and the MFA in Boston.

The ubiquity today of the likes of Hokusai’s The Dream of the Fisherman’s Wife has helped mollify reactions towards more subversive sexual imagery from Japan. The fact that a public institution could sell a postcard of a woman copulating with an octopus says a lot about the currency of this type of image in contemporary visual culture. Yet Saeki himself distanced himself from other major Japanese movements, especially from Shunga.

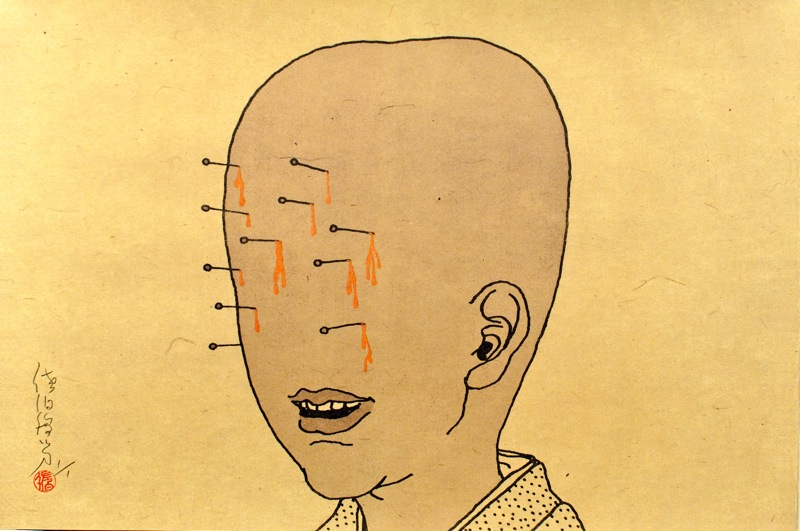

Maboroshimakura, 1972

This context does provide a valuable opportunity to examine Saeki’s work within the history of Japanese art but there are universal, fundamentally human questions Saeki has always provoked that have been overlooked: the precariousness of human nature; how attitudes towards fetish, violence and gender are shaped in a global world no longer culturally determined by geography; the aestheticization of sexuality and brutality; the dissemination of underground culture and its interaction with the mainstream; the reductive dichotomy between tradition and progress.

Just as more mainstream public audiences might be better prepared to deal with extreme explicit content now, institutional presentations have simultaneously rekindled an appreciation of the technical achievements of Japanese printmaking. Saeki’s practice was a collaborative operation—each ink drawing is overlaid with vellum sheets, marked up with colours, before being passed on to a master printer—with a long Japanese artisanal heritage. To a foreign eye, the technical components of Saeki’s practice and his aesthetic—the interiors of the houses, the figures, their clothing, the ceremonies and demons he depicts—are synonymous with Japan.

Thematically, though, Saeki does not see his work as part of a strictly Japanese canon or environment: “I do not deny the fact that just like an average Japanese person would, I grew up listening to Japanese folklore, but I feel that is not important in my work. What inspire me are the feelings of fear, uncertainty, anxiety or happiness that my sensitivities caught as a child or in my adolescence. This is for sure. I don’t know if this can be counted as traditional Japanese culture, but the films that my mother took me to as a child left a deep impression on me, and scenes from the films appear often in my work.”

Hagitsune, 1972

With Saeki, it is still unclear how much his low visibility had to do with his personal preferences. He lived practically incommunicado, with no internet, and no English; contact had to go through his agents in Tokyo. They see Saeki’s way of living as a reason for his underexposure: “We think it has to do with his personality of being very modest and reserved, and not being materialistic. And at the same time, he has a very strong will to not compromise and to believe in his art. That is why he has chosen to live in the mountains now, away from everything. So people were curious about him, but had no access.”

“I always try to put into shape the domain that is hidden deep inside the heart that cannot be described by words”

There’s an impulse on seeing Saeki’s work to want to know more about the person who made them—and why. Presently, the best that can be offered is a patchy portrait of a highly individual artist who finds beauty in the most unfathomable places. I recall he told me about some of his influences, including Nan Goldin and Judy Chicago, and that while working briefly in advertising in Osaka in his twenties, “I encountered the works by Tomi Ungerer. I felt something poisonous in his works and learned that beauty without poison is boring.”

The “poisonous beauty” in Saeki’s fearless gaze, revealing hidden parts of the self, is another distinctive trait in his work that suggests a paradoxical purity: “I always try to put into shape the domain that is hidden deep inside the heart that cannot be described by words. I want to wake up the sensibilities that are kept quiet and sleeping inside a person. As we grow older, we get used to things, but the sensitivities that you hold when you are young are pure, and it leads directly to being alive. I think that maybe people who support my works feel that and are attracted to that aspect. I wish for people who have never seen my work to encounter it, and to revive their wonderful sensitivities. When I was a boy, I used to show my picture stories to my friends and read them out loud, and they seemed to enjoy it very much. And that’s what I still do now.”

An often-overlooked element of Saeki’s work is its playfulness. This quality can be traced to his upbringing in Osaka, with its tradition of culture as a way of making people laugh, of humour as a part of everyday life—different from Tokyo culture. A desire to please and to entertain, though it might not be the first thing you think of when you see Saeki’s works, is very important, and I remember him telling us how delighted he was as a schoolboy to be able to amuse his friends, or to receive compliments from a neighbour, about his humour and skilled draftsmanship.

It is still hard to believe that Saeki is gone. I only feel regret that I didn’t get to meet him again. I promised to one day share all the stories and lessons I inherited from him, and I still intend to do so. There is a lot to be discovered and many surprises for the world. In the meantime, I will wait for him to visit me once again in my sleep, the place where he always lived most vividly himself.