Under the Influence invites artists to discuss a work that has had a profound impact on their practice. In this edition, American sculptor and painter Rachel Feinstein reflects on the impact early Renaissance woodcuts had on her interpretations of universal symbols, family, and artistic self-consciousness.

The first time I saw Madonna of the Rope Makes has a lot to do with personal history. My husband, John Currin, was having a show of his paintings at the Museo Bardini in Florence about six years ago and so I was able to see this work by Donatello, which is also held there. That family side is important: being there and seeing that work alongside my husband’s, while also being there with my children, which resonates with the mother and the child aspects.

I’ve always loved Donatello, but like a lot of people, I had mostly associated him with the very sexy boyish David sculpture, where he’s got this perfect little butt. It’s this weird idea of not having David as a very masculine symbol, but more as kind of a girlish boy. It’s very sexual and it was very revolutionary that he made David look like that.

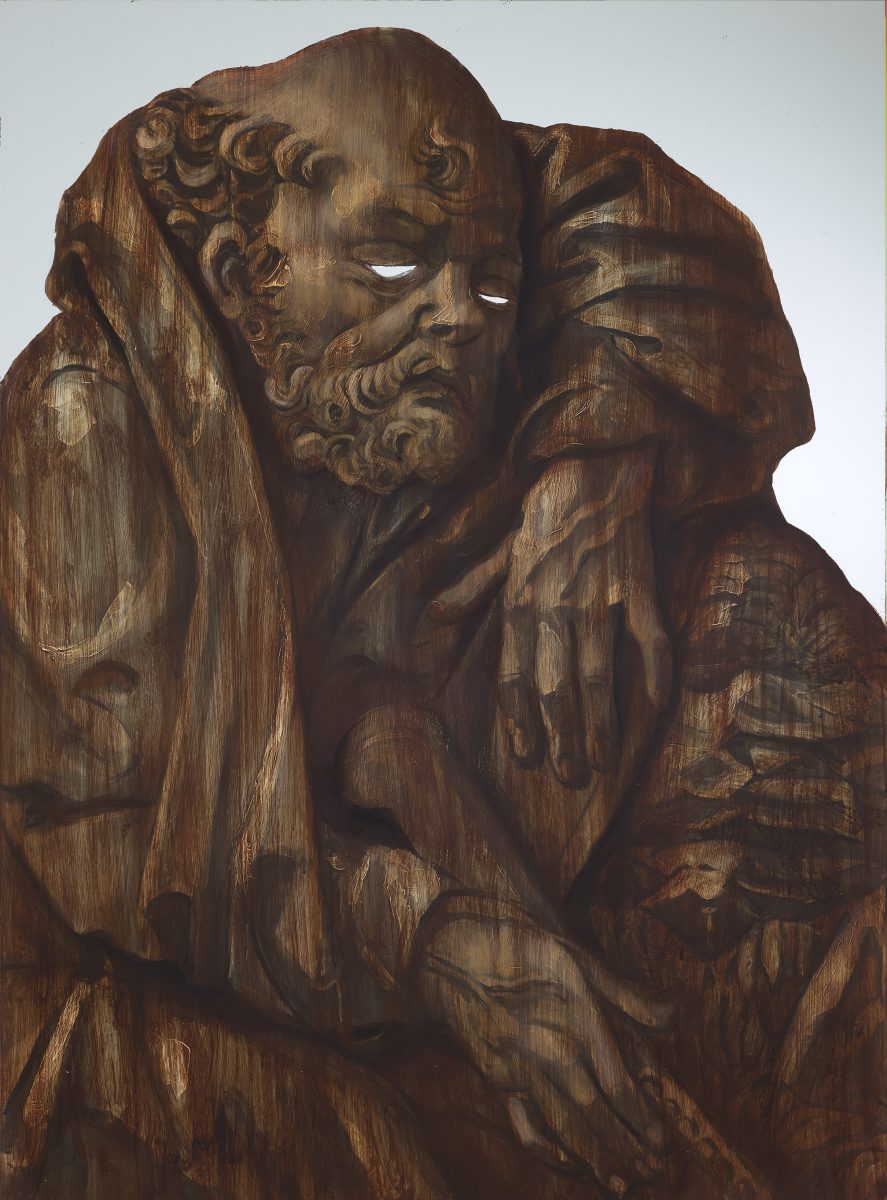

The cool thing about Madonna of the Rope Makes is that it’s decayed and it’s disintegrated and so you see the way he made it. That’s its beautiful aspect. I love that there are those little tiles behind it; then you see leather, wood. As a sculpture, seeing its construction is really important to me. You have to see this work in person, because it’s very hard to photograph: you can’t really photograph sculpture well. Sculpture is about feeling it in your body.

“You have to see this work in person, because it’s very hard to photograph. Sculpture is about feeling it in your body”

There’s just an incredible positive and negative thing going on, where the figures are so intricately carved, but on such a flat plane, that the hollow spaces between their bodies are as important as the positive spaces on their clothes. I really felt the tension in the actual material and form, as well as the symbol it is portraying.

I started just doing paintings of these famous sculptures. I used mirrors as their eyes, I became them. I was looking into their eyes as I was actually making them. It became the inside and outside, which I think about a lot with religion. Sculpture is about being tied to the earth. And painting is about being a soul and floating up and not being attached to your body. That tension is very much something I’m interested in. Your body versus your soul.

“Sculpture is about being tied to the earth; painting is about being a soul. That tension is very much something I’m interested in”

I’ve been doing Jungian dream therapy recently, which I started during Covid

. I know a lot of artists have been deeply inspired by dream analysis. The whole thing about dreams and your unconscious is that there are these symbols that go across all cultures, all times.

You don’t have to be Christian to understand the symbol of a mother and a child. That idea of everyone plugging into something, as if we’re all plugged into some strange electrical current, is just being human and being alive. I’m interested in using that as a means to express something not only outside of our time, but outside of our own politics and messages too.

“The cool thing about Madonna of the Rope Makes is that it’s decayed and it’s disintegrated”

I was a religion major at Columbia University, and there are certain stories and modes of inquiry that have stayed with me. Why is the sleeping beauty story a fairy tale but the story of Adam and Eve is somehow real? When you’re a child, everything can seem completely real. When do you lose that? Do you even? Or is it really just that our society has constructed this idea that it’s not there? My current works are about trying to get back into these ideas.

From a religious standpoint it was hard to start making these images, because my father is Jewish, my mother’s Catholic and I was raised in both. I didn’t want it to be about being Christian. There’s nothing wrong with Christianity, I think it’s a beautiful religion, but I’m interested in the idea that it comes from paganism, and paganism before that came from animism. I want to use those recurring symbols: it’s not about Jesus and Mary, it’s about a mother who has lost her child, which is really incredible and really powerful.

“The figures are so intricately carved… the hollow spaces between their bodies are as important as the positive spaces on their clothes”

My husband has been painting me since I was 22 or 23, and now I’m 50. So I see myself ageing in his paintings. It’s this weird thing of multiple layers and levels. When the works are hung, you see different other works looking in the mirror themselves. They all reflect each other. As an artist, you have to embrace the idea that there have been a lot of people that have come before you and that are basically underneath you. Everything has happened before you and you just have to acknowledge it. And move forward.

As told to Ravi Ghosh, Elephant’s editorial assistant