A nineties graduate of Goldsmiths, unlike many of her contemporaries Rachel Howard has tended to eschew the limelight. Not that that has hampered her development or the steady growth of her reputation. ‘I feel happiest in a state of failure,’ she tells Sue Hubbard. ‘I need fire in my belly to get up in the morning.’

It’s a freezing day and Rachel Howard is up from Gloucestershire, where she lives when she isn’t working in London. We meet at the Society Club, hidden down a back street in the heart of Soho. A café, cocktail bar, bookstore and art gallery where poetry collections line the walls, it feels a bit like your auntie’s rather dated front room. A throwback to 1950s bohemianism. The choice is no surprise, for Rachel Howard is an avid reader and claims that poetry gives her the same inexplicable buzz as a good painting.

She is an unusual person: a successful, sociable artist with four children (though, as she says, this would probably not be newsworthy if she were a male artist) and a close friend of Damien Hirst, for whom she once worked as an assistant. She, though, eschews the limelight and dislikes talking about herself. We have known each other for a number of years and recently did a show together, Over the Rainbow at 11 Spitalfields, which included my poems based on her powerful suicide paintings.

So we agree, as we chat over our coffee, that it feels rather odd to be doing a formal interview. I ask about her childhood and she tells me that she grew up on a farm in the north of England next to a now-redundant coalmine. ‘It’s been grassed over like Teletubbyland,’ she says, ‘as if it was never there. A whole culture wiped out by Thatcher.’ I wonder what it was like growing up in the country. ‘It gave me a taste for freedom and allowed me time to be bored, to be alone and understand what sets us apart from animals and makes us human.’ There she witnessed ‘birth, life and death. Blood, shit and guts.’ Sitting on the back of her father’s combine harvester, she could, she says, just be, just exist. ‘Nature makes you live in the moment. It just ticks away, doing its own thing.’

So how did she become an artist? ‘Well, it’s not that I woke up one morning and decided to be one. It was always there.’ Her aunt was a fabric designer and her uncle, the painter Jonathan Trowell, taught her to paint in oils. When she was 11 he introduced her to t.s. Eliot. Being a painter at Goldsmiths during the high-water mark of conceptual art must, I suggest, have felt as if she was swimming against the tide.

‘I loved that, or, more to the point, sticking with what I wanted and not changing to suit fashion. I feel happiest in a state of failure, having something to fight about. I need fire in my belly to get up in the morning. It seems ludicrous to have been a painter there at that time, but it was an incredible training ground because of the rigorous critical dialogue. I’ve never been anything other than a painter, so wasn’t in a quandary as to what medium to use. Though 24 years on, I’m now flirting with sculpture.’

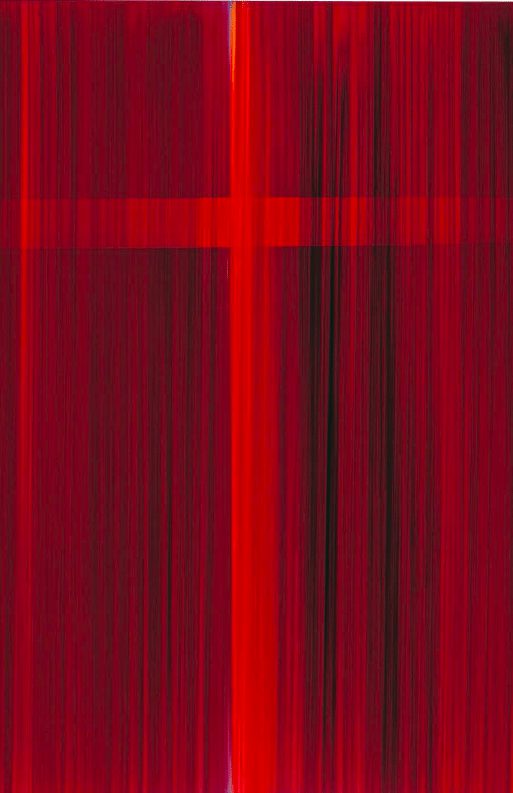

Unusually she is both an abstract and a figurative painter. Is there, I ask, any difference between the two approaches? ‘No,’ she says. ‘No difference. It’s all painting. One informs the other. I paint what I want, when I want. I’m absorbed by the world around me, the human and the natural, the political and the personal, the internal and external. How we clash and harmonize. When I painted the suicide paintings it was because I had to. When I paint about human cruelty it’s about getting things off my chest. My two recent series, Repetition Is Truth and Paintings of Violence—Why I Am Not a Mere Christian, are about the political and the human, as well as the nature of painting.’

In the past she has predominantly used household gloss, but she is now returning to oils. Why’s that? ‘I think I used household gloss because I knew about oil from an early age—what I could do with it—and wanted to flout convention. Household gloss is wonderful but limited and unforgiving. I wanted to make it do what it wasn’t supposed to do. To layer it, using the varnish and the pigment separately, as I did for over a decade. But I knew I’d always go back to oils. Oil is a beautiful medium. That’s why it hasn’t been usurped. It gives the artist more time to work on a painting, to build up layers or remove paint. It’s altogether a slower process, with a less aggressive surface. Moving on from household gloss was like leaving a lover. But I was ready for change and had gone as far as I felt I could with it.’

One of the features of her work, I suggest, is its physicality—from the suicide paintings to her abstracts in oozing red paint. ‘Thinking back,’ she says, ‘this visceral quality was probably embedded in me at Goldsmiths. I’m not at all interested in being shocking but I’m not afraid of saying what I want. Not having moved in very painterly circles, I don’t have any particular constraints. I’m free from any notion of how a painter should behave.’

So who has influenced her? ‘The American Abstract Expressionists have always given me a frisson. American painting of that period is bold and brave. I love the simplicity and power of Franz Kline, for example. I’m really influenced by everyone and no one. I love painters such as Soutine, Auerbach, Van Gogh, Gauguin, Whistler and Walter Sickert. And I’m drawn to the We Are Not the Last drawings of Zoran Music.’

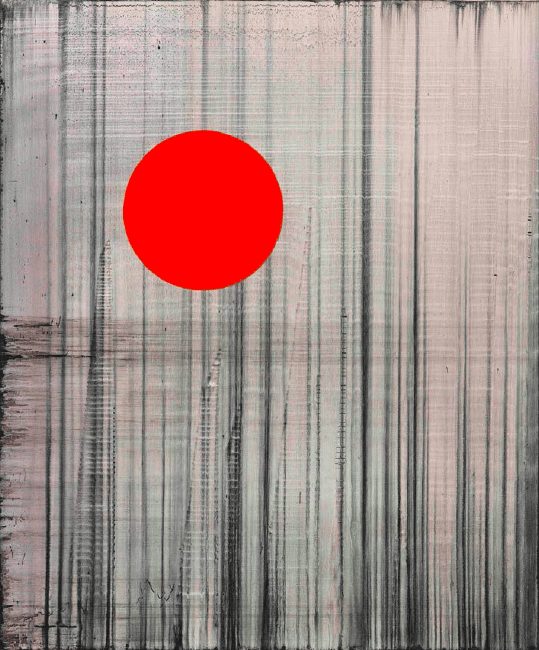

Recently she’s been asked to curate an exhibition at the Jerwood Gallery in Hastings. At Sea will open in July and consist of a number of new works made especially for the show, juxtaposed with those chosen from the permanent collection. ‘I feel really honoured to be hanging out with the likes of Keith Vaughan, John Hoyland, Walter Sickert and Prunella Clough, whose Back Drop 1933 bears a strong resemblance to the patterning in my own title painting for the show. Though I’d never seen hers before I made mine, so imagine how excited I was when I found it.’

Colour has been removed from her work, here, in order to return to the line; pushed to the background and edges so that it peeps through but doesn’t draw attention to itself. Removing colour, she suggests, is like the purity of returning to the word. It takes her back to the essence of painting. There’s something fragile, almost dreamlike, about these paintings that mirror the metaphorical, as well as literal, meanings of the show’s title. Faded memories seem to linger in Rutting Shed and Lean-to, where the ghostly presence of the buildings evokes the pitch-black net drying huts that stand on the Hastings foreshore, adjacent to the gallery. When she was growing up on the farm, the sea was only two fields away. The constant horizon line became very important, and it’s this feeling that there’s a constant truth that line never changes, which informs the exhibition at the Jerwood.

This is the first time that she has curated a show in a major public space, and I wonder what it is that she’s hoping to achieve. ‘A sense of balance. Not unlike painting a painting or creating an installation where the eye keeps moving but finds intervals of rest. This is a show by a group of painters—some alive, some dead—who share a love for painting.’

She is not afraid to experiment with new techniques. A recent visit to her studio revealed draped curtains of lace, which she’s been using as ‘stencils’ to create complex textures on the surface of the canvas. I ask if she thinks these are softer, easier than the suicide paintings. ‘In theory they are not dissimilar. They started as a homage to the invisible. Like the suicide works, they are a celebration of the unseen. A way of bringing the background into visibility. They are atmospheric. Less an exercise in what a painting can be but more an exploration or metaphor of uncertainty and instability. It’s this pursuit that’s so exciting. Not knowing what will come next: if what I’m doing will be lost or brought back from the brink. It is a very solitary endeavour. Wherever I’m working, London or Gloucestershire, I’m always alone with the thing in front of me.’

She has a busy year ahead. There is a group show in Vienna and she is working with the Bohen Foundation at a major US institution on an exhibition that will concentrate on her abstract alizarin oils on canvas: Paintings of Violence—Why I Am Not a Mere Christian. The name of the series is constructed from the title of a tract by the philosopher Bertrand Russell, Why I Am Not a Christian, merged with that of C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity. Howard attended a Quaker school in York, and in these paintings she explores issues of ‘controlled violence’, such as 9/11. For her, ‘intelligent violence is the antithesis of Bacchanalian violence. There are ten paintings that echo the Ten Commandments.’

As she gets older she finds she looks inwards more. ‘You can paint in two ways,’ she says, ‘looking in or looking out.’ Like the Roman god Janus, she looks in both directions, to the outer world and inwards into our often hidden psychological depths. The range and variety of her work—her haunting, ectoplasmic portraits taken from photographs of family and friends that were shown in 2008 at Museum Van Loon, Amsterdam, the hard-hitting suicide paintings and the visceral abstracts—give her the widest vocabulary possible to explore not only a wide range of emotions but also what it means to be a painter in the modern world.