Rachel Maclean’s self-starring videos are hard to look away from; Starbucksesque logos, preening pop stars, red-faced politicos and internet memes clash and collide in films that are at once vulgar and enthralling. The Scottish artist’s on-screen reality might at first seem like an emanation from an alternative universe, where swathes of sheep-like subjects think the same and commerce reigns free. But is it really so different from our own off-screen reality?

This interview originally appeared in Issue 27

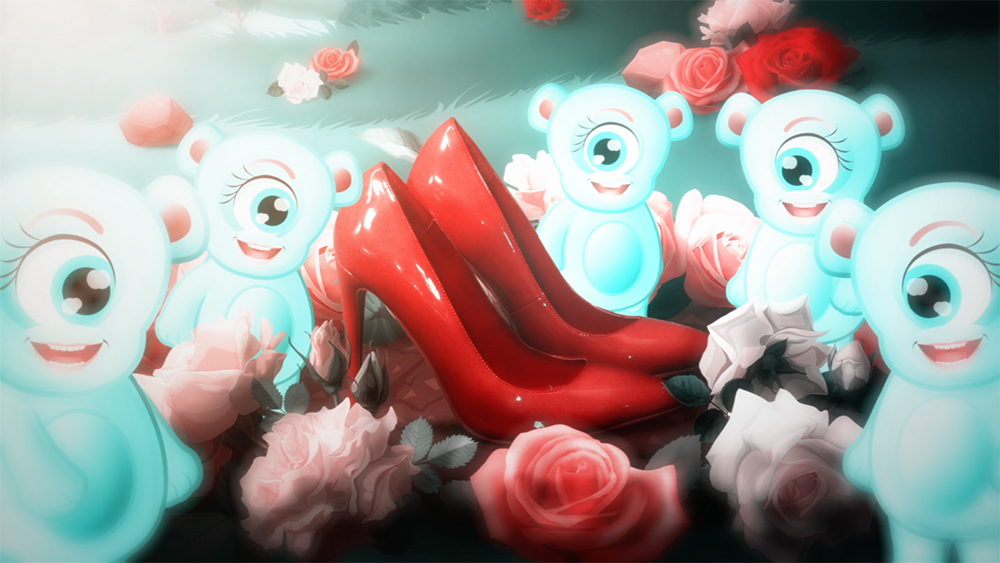

I’m interested in the play between vulgarity and entertainment in your videos; they’re a mass of branding, pop culture and consumerism, and yet there is escapism too.

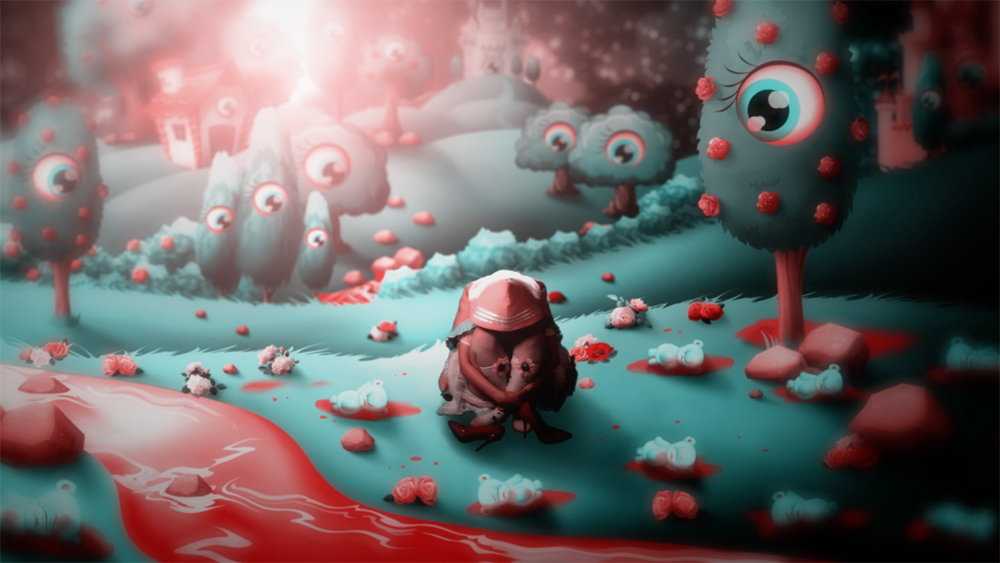

I like the idea that commercial and baroque imagery can be seductive but also there is the implication of it being decadent or too much to cope with. I like the feeling of pushing it back and forth so at times it can seem seductive, but at other times you feel like you are consuming too much. I also want you to feel that there’s an intentional lack of clarity in my work in the way it’s constructed, in the same way that you might watch YouTube, where one thing takes you to another thing and another. It’s a very contrived stream of consciousness, which is of course driven by people paying for you to look at certain things and for certain things to rise to the top.

There are logos that appear in your work that might not be entirely familiar but that hint at recognizable brands. They’re included in a very subliminal way, mirroring the way they might appear online.

I guess I want certain symbols to feel like product placement. I wanted them to feel—like with all brands: Coca-Cola, for example—that they have a mystery that implies something much greater than what they give you. I want them to feel like the symbols of a cult or talisman. They’re not just brands, they are potentially something else as well. Coca-Cola sell you happiness—there is the #choosehappiness hashtag—youth and everything you’ve ever wanted, but really they just sell you a fizzy drink. I’m also interested in products like perfume, where what you’re being sold isn’t something that you can see, it’s the smell, and that is sold on the basis of lifestyle and the fantasy ideas of what that can bring you, which are so much greater than the reality.

There’s a continuity between brands’ relationship with their audiences and patriotism and politics in your work.

With I Heart Scotland, the work that I made about Scottish identity, I was interested in the play between the pragmatic and the romantic in politics, and maybe the romantic wins out a lot of the time. Especially in the [2014 Scottish independence] referendum there was that sense of play between pragmatic idealism and the narratives of national identity which often have a very loose interpretation of history and are amalgamated through all sorts of levels of fictions, rather than what you may regard as factual truth. It feels to me like that is the nature of identity, cultural or national; it is not about truth, it is about something intangible in an even more ingrained and complicated way than a typical brand loyalty.

Brands play to people’s ideals, but they’re also led by their tastes. It’s not just that the individual is being dictated to by a brand or political party, they are also dictating how that message is packaged for them.

There is this obsession with market research and finding out what people think. You are constantly being asked what you think, you’re constantly feeding back information that is then translated to your desires. It has a lot to do with your anxieties and insecurities. I like that odd sense of identity online, which is all about companies predicting what you are going to do based on what you’ve looked at and what you’ve bought: what in the future will you buy? You know you’re being stalked by a non-specific conglomerate of companies. There will be a profile of you in a variety of different ways that explains who you are but doesn’t talk about where you come from, who your parents are or who your friends are.

Although your work addresses very adult ideas, such as politics and patriotism, there are also many references to childhood—especially Alice in Wonderland.

Children are a massive market. You’re a consumer from the day that you’re born, from the day that you can point at something. I think there’s a degree of rawness to consumerism that you experience as a child that is slightly mediated as an adult, where you just want something so much and you are being told that you should want it as well. That’s why they are such an easy market for advertisers because there is much less self-awareness, and awareness of the ways in which they’re being manipulated. There’s a real darkness to that, I think—the amount of money that is being made out of children and their desires. Well, I don’t even know if they are their desires, they’re the desires that we think children should have.

Do you feel in your role as artist that, in building such visually controlled spaces, you become the brand creator?

In a very small way I’d like to think that if I parody a face-cream advert and shift or subtly subvert that in some way, it might change the next face-cream advert that person watches. There is a subtlety there but it is also about amping up or tipping things over an edge over which they might not conventionally be tipped.

All images: Eyes to Me!, 2015, 3 min digital video. Commissioned by Film London for Channel 4 Random Acts