Isabella Greenwood reflects on the photographic archive of lesbian intimacy and reflects on how these depictions disrupt conventional representations of eroticism.

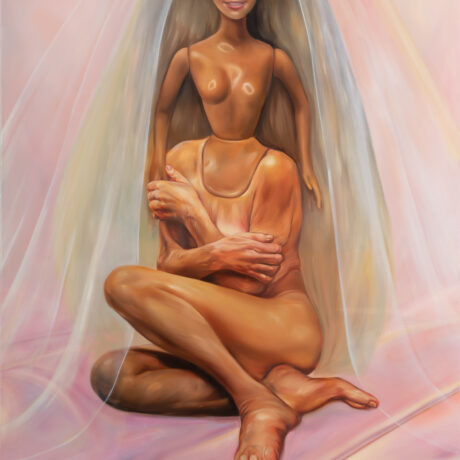

Queer intimacy has long functioned as both a site of resistance and a radical assertion of presence—visual, political, and deeply embodied. From early self-portraiture to contemporary photography, the depiction of lesbian and gay desire has consistently unsettled dominant narratives, refusing both erasure and the constrictive frameworks of respectability politics. Long before photography, queer intimacy surfaced in painterly and artistic traditions that encoded desire through gesture, allegory, and subtext. Queer intimacy in art has deep historical roots, from the Symposium fresco (c. 480–490 BCE) from the Tomb of the Diver in Paestum, depicting men reclining together in one of the earliest surviving representations of same-sex desire, alongside Athenian vase paintings framing homoerotic relationships as integral to elite male bonding, and Roman reliefs of men kissing challenge later moralistic readings of classical antiquity. Depictions of female desire, though rarer, appear in works like the 18th-century Japanese woodcut Women Embracing in a Greenhouse, continuing a tradition of sapphic sensuality in East Asian art. This lineage carries through the Symbolist movement, where Gustav Klimt’s The Virgin (1913) and Egon Schiele’s explicit depictions of same-sex intimacy disrupt conventional representations of eroticism.

More overtly, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s Rosa La Rouge et une amie (c. 1895) captures lesbian desire within the demi-monde of fin-de-siècle Paris, while Romaine Brooks redefined portraiture with The Amazon (1920), asserting a bold butch identity. From antiquity to the modern era, these works inscribe queer intimacy into art history as both subversive and enduring.

Photography, however, introduced a new immediacy—transforming queer desire from the allegorical into the documentarian, carving out a space for lived erotic realities to exist beyond metaphor.

Phyllis Christopher’s black-and-white images, spanning 1988 to 2003, exemplify this shift, capturing lesbian intimacy with a radical authenticity that had seldom been documented through such an unfiltered lens. Her work resists mainstream narratives of sexualised consumption, instead constructing a visual lexicon of desire rooted in community, care, and political urgency. As Christopher recalls: “When I started taking these photographs, nobody talked about sex in the mainstream, and certainly not lesbian sex. At the time, our friends were dying from HIV/AIDS. We were fighting for visibility, proper medical attention, and basic civil rights.” Here, the photographic image is not merely an aesthetic exercise—it is a form of resistance, an insistence on existence amid systemic erasure.

Christopher carefully delineates between the erotic and the pornographic, rejecting the latter’s instrumentalisation of desire in favour of a more sensorial, affective visual language. “I never had a burning desire to create pornography. The joke about pornography is that it’s just erotica with bad lighting, and my lighting is really good. But I had an interest in the lesbian visual language.” Her images do not seek to replicate heterosexual paradigms of sexual representation but instead cultivate a visual intimacy that is playful, embodied, and resistant to commodification. In refusing to frame lesbian desire as either transgressive spectacle, Christopher’s work engages in a broader critique of the ways in which queer eroticism is often denied legitimacy within both art history and the public sphere.

Tee Corinne, active in the 1970s and 1980s, pioneered a radical visual language of queer desire, centering lesbian sexuality in ways that directly countered its historical invisibility. Her work was groundbreaking not merely in its explicit depiction of lesbian eroticism, but in how it foregrounded female pleasure outside the male gaze—offering an autonomous, self-determined vision of intimacy.

During the early 1980s, Corinne relocated from San Francisco to a lesbian commune in Oregon, seeking refuge from a period of severe depression. There, she played a pivotal role in organising feminist photography workshops, subverting traditional academic structures by naming them ovulars—a deliberate linguistic departure from “seminars,” whose etymological root (“semen”) signified patriarchal dominance. While second-wave feminism has often been critiqued for centering white, middle-class, heterosexual women, Corinne’s work operated from a more inherently intersectional position, capturing bodies and intimacies that defied monolithic representations of female sexuality. Her images rejected both the desexualisation of lesbians in mainstream feminist discourse and the exploitative framing of queer desire in heteronormative pornography, carving out a space where lesbian eroticism was neither fetishised nor erased but affirmed as an intrinsic site of pleasure and self-representation.

Del LaGrace Volcano’s work is often categorised within the realm of queer and trans representation; it resists fixed categorisation, instead operating within the fluid, liminal spaces of gender, embodiment, and desire. “My work is driven by a need to make visible what has been forced to remain hidden,” Volcano states, positioning their practice as an intervention against the historical erasure of gender nonconforming bodies. Volcano’s work, much like Christopher’s and Corinne’s, refuses the reductive framing of queer intimacy as either utopian ideal or transgressive aberration. Instead, it embraces queer embodiment as a lived and ever-expanding process—depicting the legitimacy of desire beyond the constraints of the heteronormative gaze.

Catherine Opie’s work occupies a crucial space within the visual history of queer intimacy, particularly in its insistence on the normalcy of lesbian domestic life. While much of queer representation has historically veered between hypervisibility—framed through the lens of deviance or spectacle—and complete erasure, Opie’s photographs offer a counterpoint: a quiet, quotidian reality in which lesbian love, care, and kinship unfold in domestic spaces.

Her Domestic series (1995–1998) documents lesbian couples and families in their homes, capturing moments of tenderness, routine, and intimacy that refuse the notion of queerness as inherently transgressive. Images like Gina & April, Minneapolis, Minnesota (1998) and Melissa & Lake, Durham, North Carolina (1998) present relationships not as political statements but as lived realities, challenging the historical exclusion of queer lives from the canon of domestic portraiture. Here, lesbian intimacy is neither radicalised nor exoticised—it simply exists.

Yet Opie’s practice is not limited to domestic realism. In earlier works like Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993), in which she incises an image of two stick-figure women holding hands into her back, she confronts the wounds inflicted by queer invisibility, literalising the pain of exclusion while simultaneously affirming her desire. This oscillation between vulnerability and defiance runs throughout her oeuvre, suggesting that the politics of queer representation lie not just in grand gestures but in the quiet insistence on presence, care, and belonging.

By rendering lesbian domesticity visible, Opie challenges the art-historical tradition in which intimacy between women has either been aestheticised for male consumption. Her work thus intervenes in both photography and queer historiography, asserting that desire—especially lesbian desire—need not always be radical to be significant.

Zanele Muholi’s photographic practice operates at the intersection of visual activism and queer representation, centring Black lesbian, trans, and non-binary identities in ways that challenge both historical erasure and contemporary violence. Of Love and Loss, a series deeply embedded in themes of intimacy, vulnerability, and mourning, resists the tendency to depict queer love solely as transgressive or oppositional. Instead, Muholi’s images foreground the tenderness and care that sustain queer communities in the face of systemic marginalisation.

In works like Being (2007), which documents lesbian relationships in post-apartheid South Africa, and Faces and Phases (2006–present), a portrait series honouring Black queer lives, Muholi reclaims the right to visibility. Their practice actively confronts the colonial and heteropatriarchal visual economies that have historically rendered Black queer bodies either hypersexualised or invisible. Love and loss, in this context, are inextricable—each image a quiet act of defiance against the violence that seeks to erase such intimacy.

This act of radical visibility finds resonance in the work of Laura Aguilar, a pioneer of Latinx lesbian representation, whose photographs similarly centre queer embodiment beyond the constraints of respectability politics. Aguilar’s images are deeply rooted in intersectionality, addressing race, size, queerness, and disability in ways that reject both fetishisation and erasure. Her Plush Pony series (1992) documents lesbian life within a Latinx bar in Los Angeles, offering an unvarnished yet deeply affectionate portrayal of queer social spaces.

Queer photography has expanded in scope, embracing both the immediacy of lived experience and the aesthetics of intimacy. Contemporary artists like Spyros Rennt capture queer intimacy, meditated between both rave and nightlife culture, and the softness of natural light and warm bedroom sheets. Here, queer intimacy is both an aesthetic of play/ and of care. Rennt’s work resists the binary between public and private, instead revealing how queer desire manifests across these threshold, while Cherry Au Hon I, non-binary, Macanese born photographer, captures intimate portraits of queer people from across Europe and Asia, photographed in their own environments – be that a houseboat on London’s canals, a caravan in Berlin, or a vintage shop in Taipei.

In a world that seeks to police and domesticate desire, queer intimacy remains an incandescent force.

The photographic archive of queer intimacy functions not just as documentation, but as a political intervention: a challenge to erasure, a disruption of normativity, and an assertion of erotic legitimacy within both fine art and activism. From the historical subtexts of Renaissance allegory to the defiant visual vocabularies of Phyllis Christopher, Tee Corinne, Del LaGrace Volcano, Catherine Opie, Zanele Muholi, Laura Aguilar, Spyros Rennt and Au Hon I, queer intimacy is revealed not as monolithic, but as multiplicity—at once political, poetic, and profoundly embodied. These images resist the historical burden of invisibility, refusing both assimilation and fetishisation, insisting instead on presence: the tactile, the everyday. Queerness, as visualised through these photographic works, is neither an abstract utopian ideal nor a fixed site of transgression. Rather, it exists in the liminal spaces between pleasure and grief, domesticity and nightlife, eroticism and resistance.

Words by Isabella Greenwood