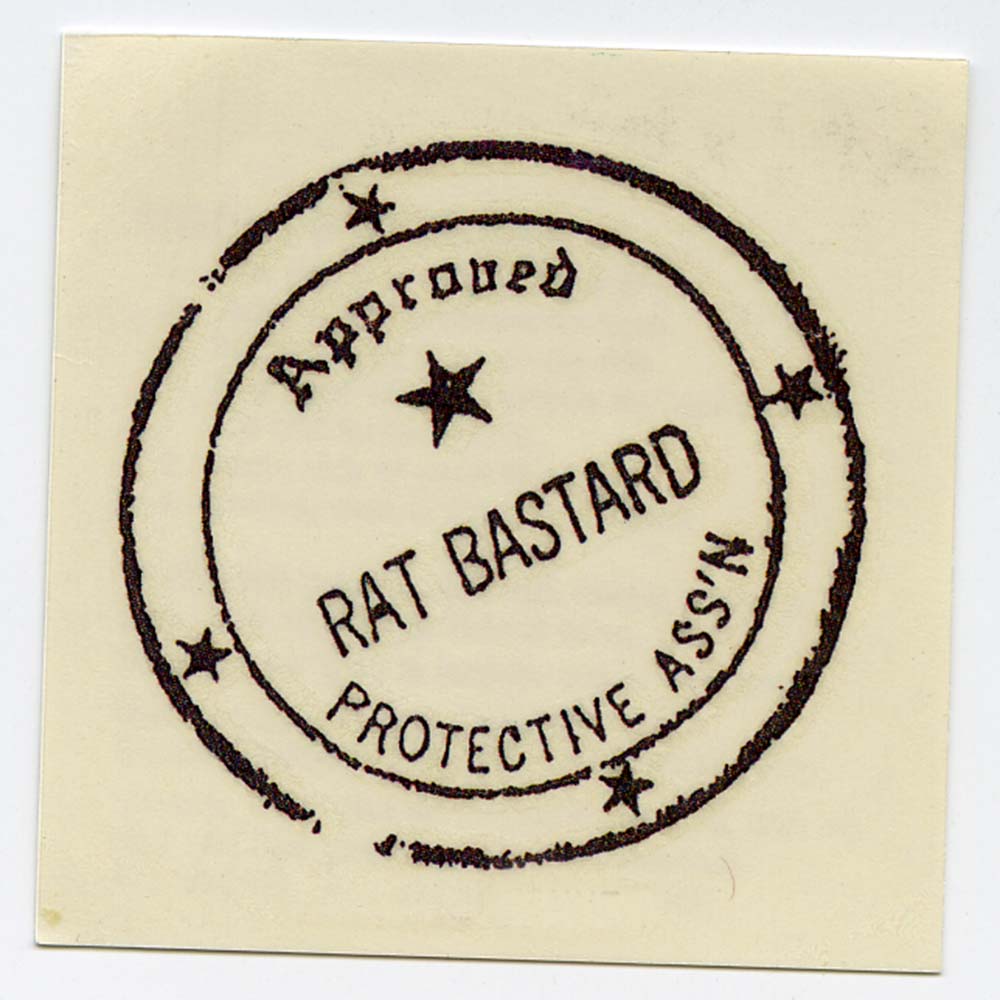

One of the first groups to define the classic collective outsider mentality was the Rat Bastard Protective Association, summoned into being by Bruce Conner in 1950s San Francisco. Their distinctive stamp of approval was used to unify a group of artists who felt alienated from mainstream postwar US society. Anastasia Aukeman tells their story.

This feature originally appeared in Issue 29

The story of the Northern California experience typically begins with the California Gold Rush of 1848, which transformed San Francisco from a small settlement into a metropolis in the course of a few years. Tens of thousands of gold seekers and immigrants from virtually every continent travelled to San Francisco, by land and by sea, and a new society came rapidly into being. The city attracted those who were willing to take great risks and soon established itself as a place—even if only in the public imagination—of unlimited opportunity, autonomy and self-determination.

A century later, in the 1950s and 1960s, San Francisco was still a diverse, tolerant city, attracting young people from all over the world with its promise of unlimited individual and aesthetic freedom. The arts precipitated another great westward migration, as post-World War II coteries like the Beat poets took hold of the national imagination and drew to San Francisco numerous young artists, writers and filmmakers from around the United States, eagerly fleeing the conservatism and conformity (real or perceived) of their own hometowns.

The poet Michael McClure was one such poet, leaving his hometown of Wichita, Kansas and moving in 1956 to a building in San Francisco’s Western Addition that was already home to an array of artists, poets and musicians. Because a number of Bay Area figurative painters were living there when he arrived, McClure dubbed the simple four-unit structure “Painterland”. Between the early 1950s and 1965, the building located at 2322 Fillmore Street became the centre of the close-knit communities, galleries and other alliances that formed nearby. It was a latter-day, West Coast Bateau-Lavoir: home, studio and meeting place to a revolving cast of artists, filmmakers and poets, not unlike the dark, flimsy buildings in the Montmartre section of Paris that provided a fertile living, working and meeting place for Picasso and his compatriots in their early years.

McClure was an especially close friend and mentor to the artist Bruce Conner, whom he met as a boy in Wichita. Eager to expand his artistic community in San Francisco, McClure wrote frequently to Conner, urging him to move to San Francisco. Conner and his new bride, Jean Sandstedt, moved there on 1 September 1957. The Conners lived at 2322 Fillmore Street for several weeks before moving to a three-room apartment around the corner on Jackson Street, a few doors from Wallace and Shirley Berman and their son, Tosh, since there were no vacant units in the Painterland building.

Despite being new to the scene, Conner announced just months after arriving in San Francisco that he was starting a collective of sorts: “I started a group called the Rat Bastard Protective Association, sent letters out to Joan Brown and Manuel Neri and Wally Hedrick and Jay DeFeo and Art Grant and Fred Martin and a few other people I can’t remember right now. Told them that they were members of the organization and I was the founder and president, and that they should pay their dues right away. The next meeting was next Friday at my house and that we would have meetings every three weeks at a different person’s house.” As a newcomer, Conner was most likely eager to consolidate his inclusion in the community and saw the association as a way to achieve this end. He placed himself firmly at the centre of this cohort of young artists by forming a group and appointing himself its president.

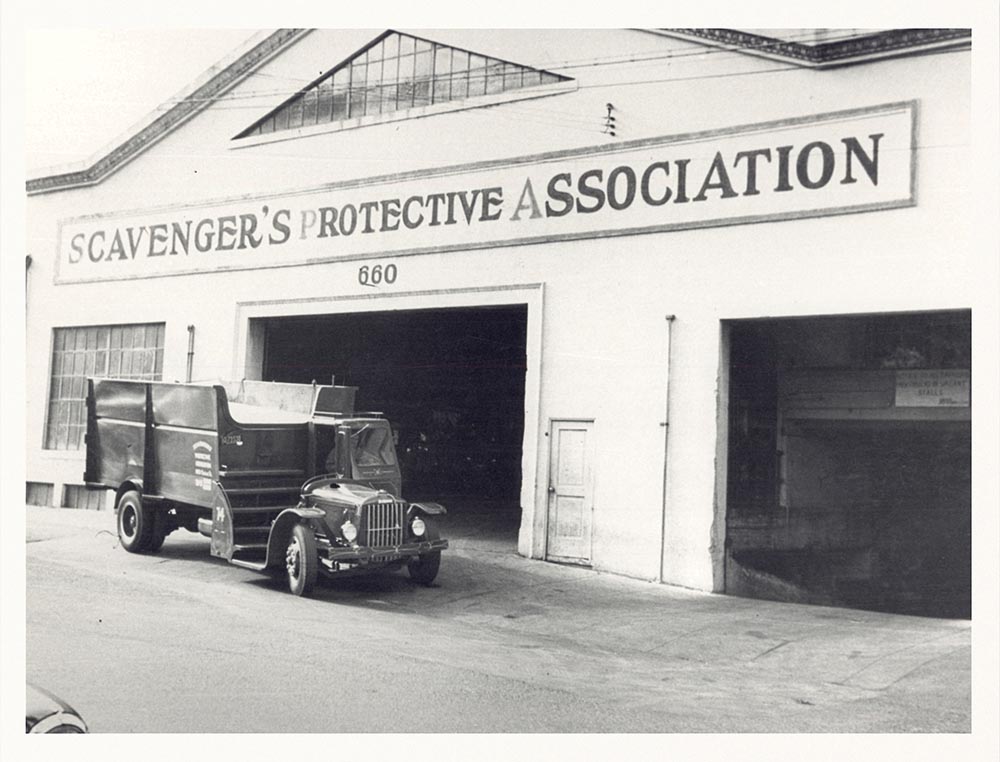

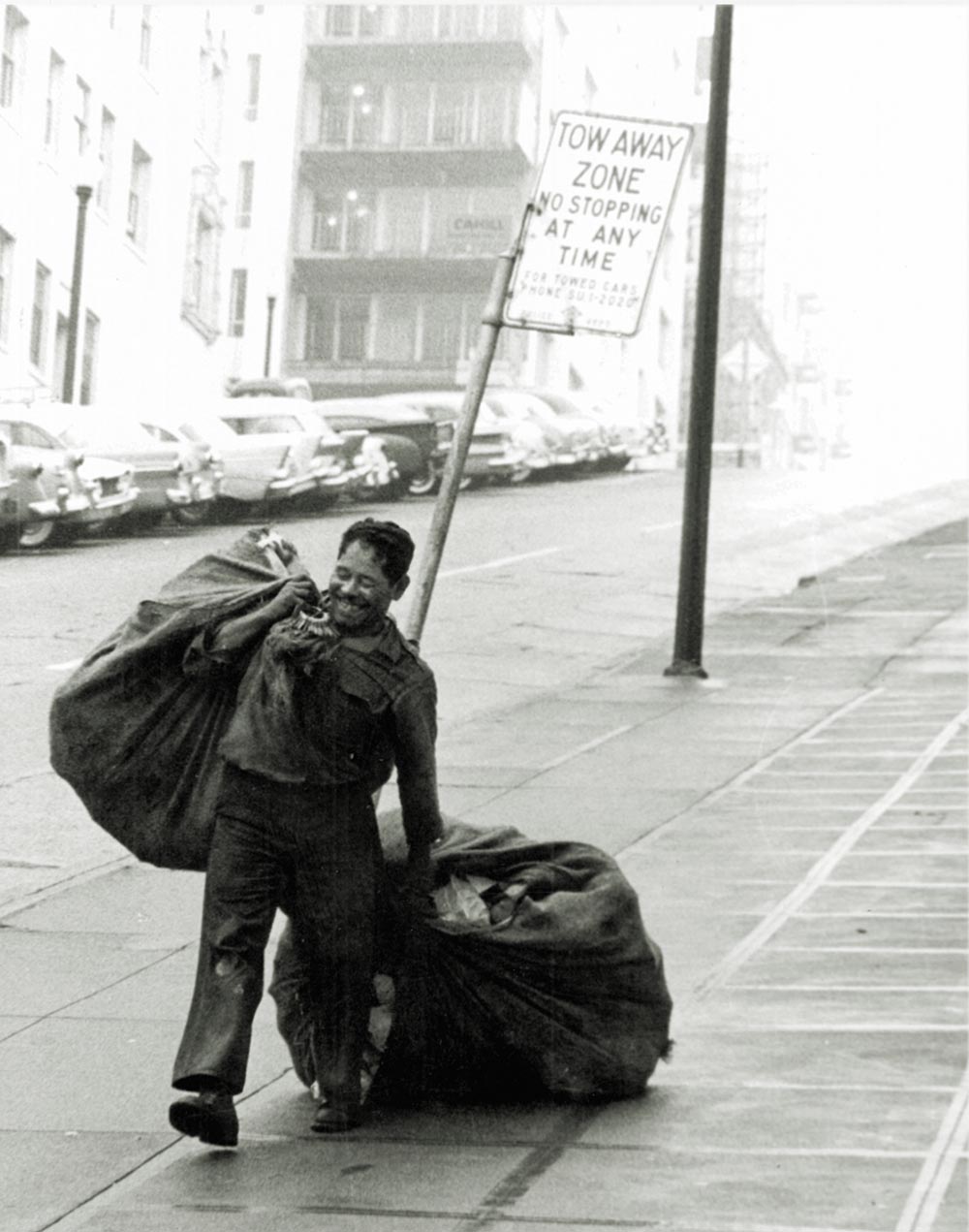

Conner derived the name Rat Bastard Protective Association (RBPA) by combining the name of a San Francisco trash collectors’ organization, the Scavengers Protective Association, with an expression adopted by McClure, who was then the district manager of a chain of Vic Tanny gyms in San Francisco. He related that his boss’s “favourite cuss word was Rat Bastard. So I picked that up, and Bruce picked that up from me.” Many of the parties held at 2322 Fillmore Street began as meetings. Conner once called for a meeting on the Golden Gate Bridge (for which only Neri showed up). “He instructed me to jump off the bridge,” Neri recalled with a laugh.

Conner told the curator Peter Boswell in 1983 that the name Rat Bastard was fitting because, like the garbage collectors and the rougher types of men who frequented gyms in those years, he and his friends saw themselves as “people who were making things with the detritus of society, who themselves were ostracized or alienated from full involvement with society”. The group played in jazz bands, ran alternative galleries, and lived, worked and exhibited together in the Fillmore neighbourhood for the better part of a decade. Conner even designed what he called the “approved seal of the Rat Bastard Protective Association”, a rubber stamp to be used by members to sign their works. Villa recalled that Conner also used the stamp to signal his approval—of just about anything. Like so much of Conner’s work, the seal was multivalent: it signalled belonging, it commodified, it spoke of hubris and it was funny. Most of all, the stamp was designed to unify a group of artists who felt alienated from the mainstream and deprived of institutional acceptance.

The name Rat Bastard Protective Association itself was a slur—anti-social, with connotations of garbage, clearly designed to offend. The formation of the group and its feigned implied exclusivity was a parody of what Conner once described as the “in-crowd, art-world sort of thing, where things did not depend on what it was you actually created, but on what your pedigree might be or who had your work”.

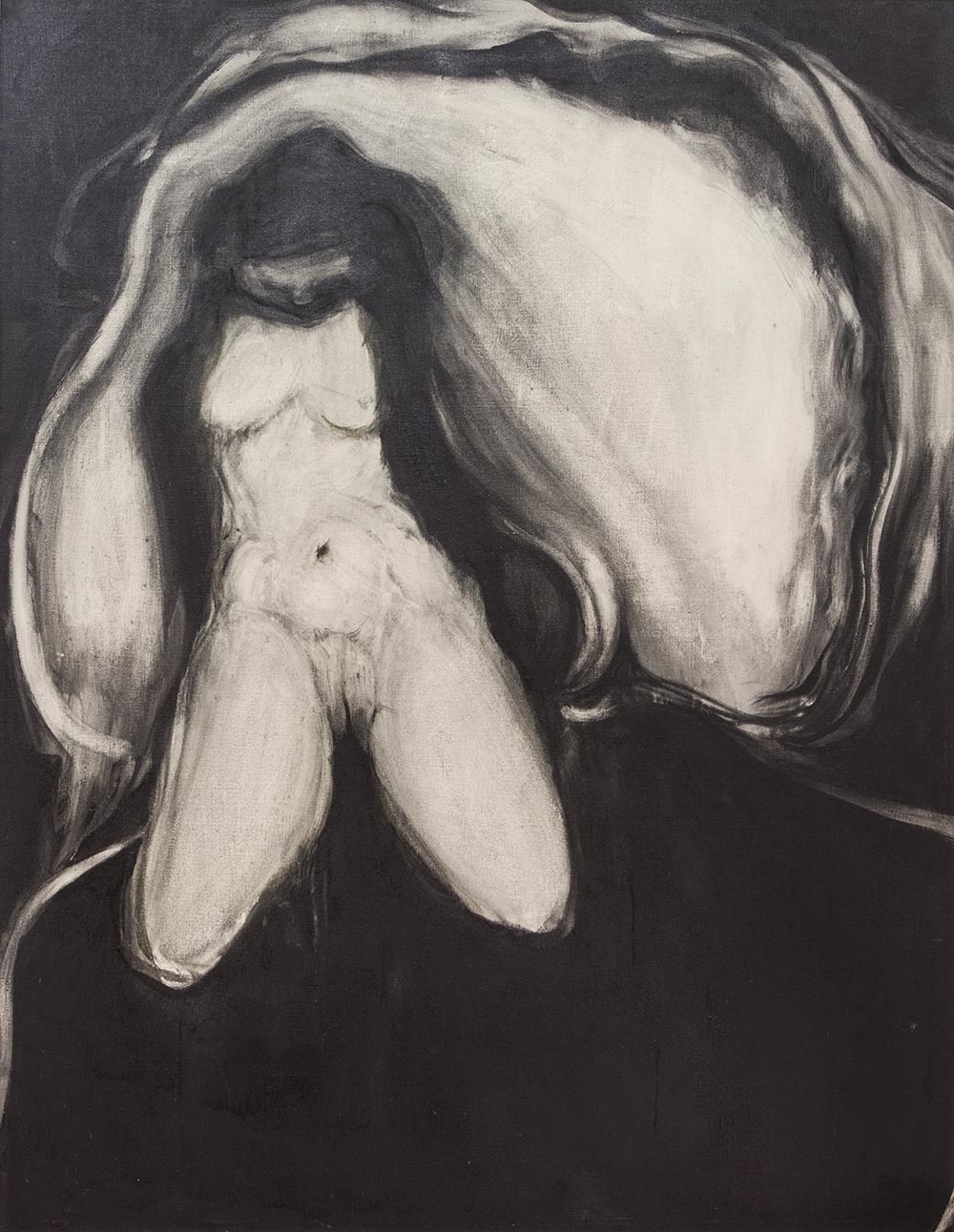

The poet Jack Foley connected the rat bastard name to the act of self-mythologizing—except that in the case of the Rat Bastard Protective Association, the mythologizing was not selfaggrandizing but self-denigrating: “to see oneself as outcast, as waste material.” Joan Brown addressed this aspect of their practice when asked about her involvement: “The point was that there was really no point. That was the attitude at that time. A lot of us used rats in our images. I certainly did. That went along with the literally ratty found objects that we all used.”

There is also a strong element of the prankster in the Rat Bastard name and in the activities of the group. The Rat Bastards came together well before the year 1964, when Ken Kesey and thirteen friends boarded a famous psychedelically painted bus they dubbed “Furthur” (or “Further”, depending on the day and mood), for a drug-fuelled road trip from California to New York City. (Tom Wolfe chronicled the trip Kesey envisioned as a re-enactment of the great western migration in reverse and called his Merry Pranksters “the unsettlers of 1964, moving backwards across the Great Plains”.) They embarked on their journey—their “trip”—a little more than a hundred years after the California gold rush. Kesey was deliberately reflecting and remarking on what was becoming a personal and collective sense of disillusionment and fragmentation among young people in the postwar United States. But Conner and his Rat Bastard friends had already felt this profound dissatisfaction with the status quo in the 1950s, and the founding of the group and its members’ artistic practices—continually switching mediums to avoid being pinned down, playing pranks as a way to defy categorization, dropping out of the art world but nonetheless making artworks—reflected that discontent.

Conner also endorsed works anonymously with the Rat Bastard stamp. Villa recalled other ways in which Conner used the stamp: “He would look at signs on telephone poles and [say,] ‘God, that’s a great advertisement.’ Clunk. Even the waitress with her new black, blue, white leotards got stamped right on the ass. Rat Bastard. He’d stamp tables, menus, it was just this fantastic piece that he was doing all the way through.” Irreverent, wily and audacious, Conner reflected the tradition of San Francisco artists who embraced their role as heirs to the Dada legacy. Now he threatened to go further by abandoning authorship altogether, and he wanted to take his friends with him.

In the summer of 1958, the Rat Bastards had a group exhibition at the artist Dimitri Grachis’s Spatsa Gallery at 2192 Filbert Street, not far from Painterland. According to one attendee, “Conner had hung some of his own ‘rat’ pieces (of which there were many during that period, characterized by the use of scavenged materials and the inclusion of small pouches). The ceiling was done in fur. Another picture was a Clyfford Still parody by Brown, a canvas painted with peanut butter and jelly.” Alvin Light’s expressive wooden sculptures were also included in the show, as was a “big, beautiful red and green abstract landscape painting” by Neri, according to Villa, along a Villa coffin piece. “The cat always slept in the coffin,” he recalled with a laugh.

Conner, Dave Haselwood, McClure, Neri and Villa also organized a Rat Bastard parade through North Beach and all the way to the Spatsa Gallery to celebrate the show. According to Conner, the parade was totally unannounced and included “banners and standards”. Conner recounted how the parade grew: “All of a sudden there were about two hundred people walking down Grant Avenue and across Broadway. There was a poetry duel between Philip Lamantia and some bullshit poet who had moved in from New York for about two months.” Several poets and artists led the parade, carrying the wooden coffin piece by Villa. It was wrapped in red, white and blue parade bunting that Villa had found on the street. Joan Brown placed on the coffin a plaster wreath she had made for it, with the inscription “He died for love”. Neri was teaching Brown how to use plaster that summer, and the inscription was most likely a playful allusion, not only to Villa’s coffin piece but also to a flirtation between the two of them; she and Neri began living together not long afterwards.

The Rat Bastard parade was the kind of spontaneous event that came to define the San Francisco scene. Unlike other Bay Area groupings, such as those who participated in Wallace Berman’s hand-printed, personally distributed literary journal Semina or the poets gathered around Jess and Robert Duncan, the Rat Bastard Protective Association was not organized around a highly charismatic figure or figures. Conner set the group in motion, but his personality differed fundamentally from that of a quasi-sacral figure—which Berman could not but be—and he was too young to act as mentor, unlike Jess and Duncan.

While an iconoclastic spirit characterized many of the activities of the Rat Bastard Protective Association, the artists living and working in and around 2322 Fillmore Street were deeply committed to their work and, in most cases, aware of its significance, though they were conflicted about the consequences of fame. They may have been geographically isolated from the vibrant commercial art market in New York and from immediate access to European influences, but they were part of a distinctively close community that was engaged in an interrogation of a larger aesthetic and social theory, with roots in historical traditions. That their work developed in ways that diverged from (what became) canonical modernism after World War II makes this period a fertile area of discussion.

“The Rat Bastard Protective Association” exhibition, curated by Anastasia Aukeman, runs at The Landing in Los Angeles until 7 January. Aukeman’s “Welcome to Painterland: Bruce Conner and the Rat Bastard Protective Association” is published bt the University of California Press.