Put on the headset and blink. You are standing in a forest clearing. The sun dapples through the feathery trees overhead. Around you is a swirling wall of fog, or maybe it’s dust from the sandy floor. There is a murky abyss in the ground. Do you want to try to look or maybe to fall in?

Of course, you choose to fall in; maybe you attempt a running jump. And fall you do, plummeting through a wormhole lined with glistening, wobbly flesh and viscera, ever deeper into what appears to be a human body. It’s like looking through an endoscope, except you are the endoscope, and you seem to be freefalling through your own arteries. Or perhaps you are delving into your own psyche, starting with the arboreal dendrites and vascular cell walls of the void, hurtling through an axon and dissolving into your own nerve endings.

Perhaps gut-dropping vertigo is getting too much. You take off the headset and realize you’re actually at Art Basel Hong Kong, in the rather beige HTC Vive-sponsored lounge, the megafair’s first “official VR partner”. You are experiencing Anish Kapoor’s Into Yourself, Fall, an immersive experience designed to physicalize the disorienting effects of virtual reality—or looking into one of Kapoor’s voids, for that matter. The work is produced in collaboration with Acute Art, a VR startup that launched last autumn with commissions from Olafur Eliasson, Jeff Koons and Marina Abramović.

“VR is at once freeform and radically constrained: it promises both a new way of seeing and a total-body immersion, a kind of carceral gesamtkunstwerk.”

The artist is present here too, with Rising, another Acute Art collaboration on view in the lounge. In fact, the artist, or rather a digital avatar of Abramović, is drowning in a glass tank—not in her own tears, but because of the rising sea levels caused by the global climate crisis. She takes the viewer on a swooping tour of Acute Art’s impressive 3D modelling and virtual terraforming skills via an Arctic environment in which waves batter crumbling icebergs, before returning to her tank to entreat you to make a pledge to save the environment. (An app is forthcoming.) “The choice is only yours,” she intones in a preview video, sounding like nothing so much as a New Age Captain Planet with the anticapitalist bits taken out. Should you decline to pledge, the water levels rise and Abramović’s sim drowns.

Despite its markedly more sophisticated interface, virtual reality is something of a return to the interactive fiction games of the early nineties, even as it purports to extend the experience of a first-person shooter. Imagine yourself here, in this other place, they tell you, before going on to describe, and arguably circumscribe, exactly what that “here” contains. VR is at once freeform and radically constrained: it emphasizes the visual (consider Oculus Rift, the headset name) and promises both a new way of seeing and a total-body immersion, a kind of carceral gesamtkunstwerk. Unlike most video games, which have a finite number of controls (or commands or console keys), with VR—as with text-based adventure games—you’re entirely on your own.

Although VR has only borne its current moniker since its coinage by Jaron Lanier of VPL Research in the mid-1980s, the technology has been around far longer. Its progenitors include nineteenth-century stereoscopes and the familiar View-Master, as well as the Morton Heilig’s Sensorama, and Ivan Sutherland’s head-mounted “Ultimate Display” which laid the ground for the headsets and goggles we are more familiar with today. It’s worth noting too that Lanier’s term, like the more recent 2010s VR revival, emerged in concert with the new products (goggles and gloves) he developed, although its exorbitant prices ($9000 and up) prohibited its mass adoption.

We might further locate VR’s origins in eighteenth and nineteenth-century panorama paintings, displayed in custom-built circular buildings that were carefully designed to give the viewer the sensation of stepping into a scene. A contemporary analogue can be found in the surround video popularized by the New York Times’s Daily 360 feature and apartment listings alike. Google’s Arts and Culture 360º Video project meanwhile means that art museums aren’t (too) far behind, with the Met, Moma, the British Museum and the Louvre, among many others, all offering their own virtual experiences. Some institutions, such as New York’s New Museum, have taken this further, with a virtual reality exhibition and app featuring Rachel Rossin, Jon Rafman and Jacolby Satterwhite among others. Examples abound; the global VR market is currently some $11 billion strong and is projected to grow to $60 billion by 2023, and everybody wants a piece of it.

The sociological concept of digital dualism convincingly argues that we are so technologically enmeshed and interpellated that to distinguish between “the virtual” and “the real” is a conceit at best. And weren’t we always already cyborgs anyway, with our pacemakers and powered eyeglasses and other prosthetics, long before we glued phones or other expensive headsets to our faces? The exciting thing about VR is that you actually use your body, moving forwards or backwards in your physical (and by extension virtual) environment, and perhaps even interacting with it if you’re kitted out with gloves or another haptic technology. And the equally terrifying thing about VR and its attendant wave of technoptimism is that you actually use your body, a body filled with all the bundled limitations of flesh and blood that Kapoor’s video can only begin to intimate, along with a nervous system that is barely calibrated to deal with the pressures of everyday life, let alone a generated algorithmic iteration too. Consider the threat of ocular herpes from using shared, unsanitized headsets or the phenomenon of virtual reality sickness.

“Weren’t we always already cyborgs anyway, with our pacemakers and powered eyeglasses and other prosthetics, long before we glued phones or other expensive headsets to our faces?”

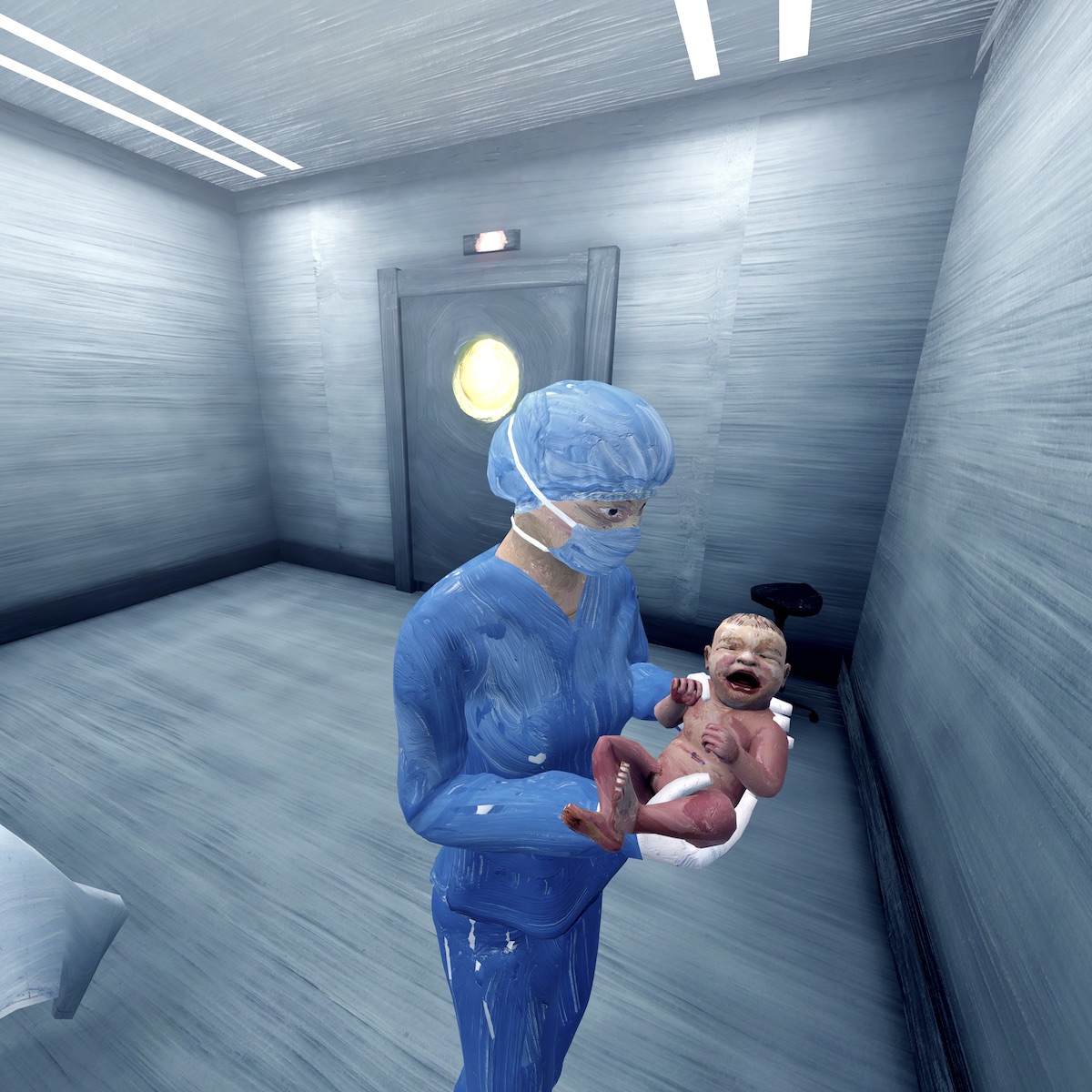

Still, the example of Acute Art suggests that technowariness is no match for the allure of capital. Rather more interesting are some of the other VR works on view at the fair, which include Timur Si-Qin’s Mirrorscape presentation in the Discoveries section, which leverages simulated natural environments to propose a new mysticism for the Anthropocene in the second iteration of his New Peace campaign. Especially intriguing is Yu Hong’s hand-painted VR piece She’s Already Gone in the Kabinett sector, in which the viewer watches a woman age through four stages of life as she concurrently seems to move back through time: she is young in a modern-day hospital, and old in a scene from China’s earliest recorded history. Kapoor and Abramović’s works, however, are both each artist’s first forays into VR and it’s difficult to shake the whiff of market-ready expediency. And yet in the face of so much gimmickiness (and undoubtedly more to come) is the example of the Hirshhorn in Washington DC, which innovatively turned to VR to make last year’s Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirrors accessible to wheelchair users. A mobilization of a new technology that actually facilitates and perhaps eventually extends life instead of aestheticising it with all the sincerity of a teleshopping host? It’s hard to argue with.